Summer of Blood: The preservation of rare birds

If Mario Bava's The Girl Who Knew Too Much can be identified as the first giallo, it's mostly because of hindsight: it is ground zero for the form, the earliest ending point for most of the tropes that came to define the subgenre. But at the same time, it's notable as much for the ways in which it is unlike other gialli as the ways in which it is like them, something of a hothouse for ideas in which some lines of inquiry were pursued and others ignored; in this it is to the giallo as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is to the slasher film. To continue the metaphor, Bava's 1964 Blood and Black Lace (a colorful mistranslation of Sei donne per l'assassino, or Six Women for the Killer) is the Halloween of gialli: the film that really nailed down almost all of the "rules" for the style, with the understanding that "giallo" is a much less specific category than "slasher", based on mood, style and narrative ingredients rather than a easily-identified narrative structure. But, like Halloween, Blood and Black Lace wasn't the film that made the subgenre explode into a hugely popular phenomenon. That wouldn't happen for another six years.

Tonight, then, we shall consider the Friday the 13th of the gialli.

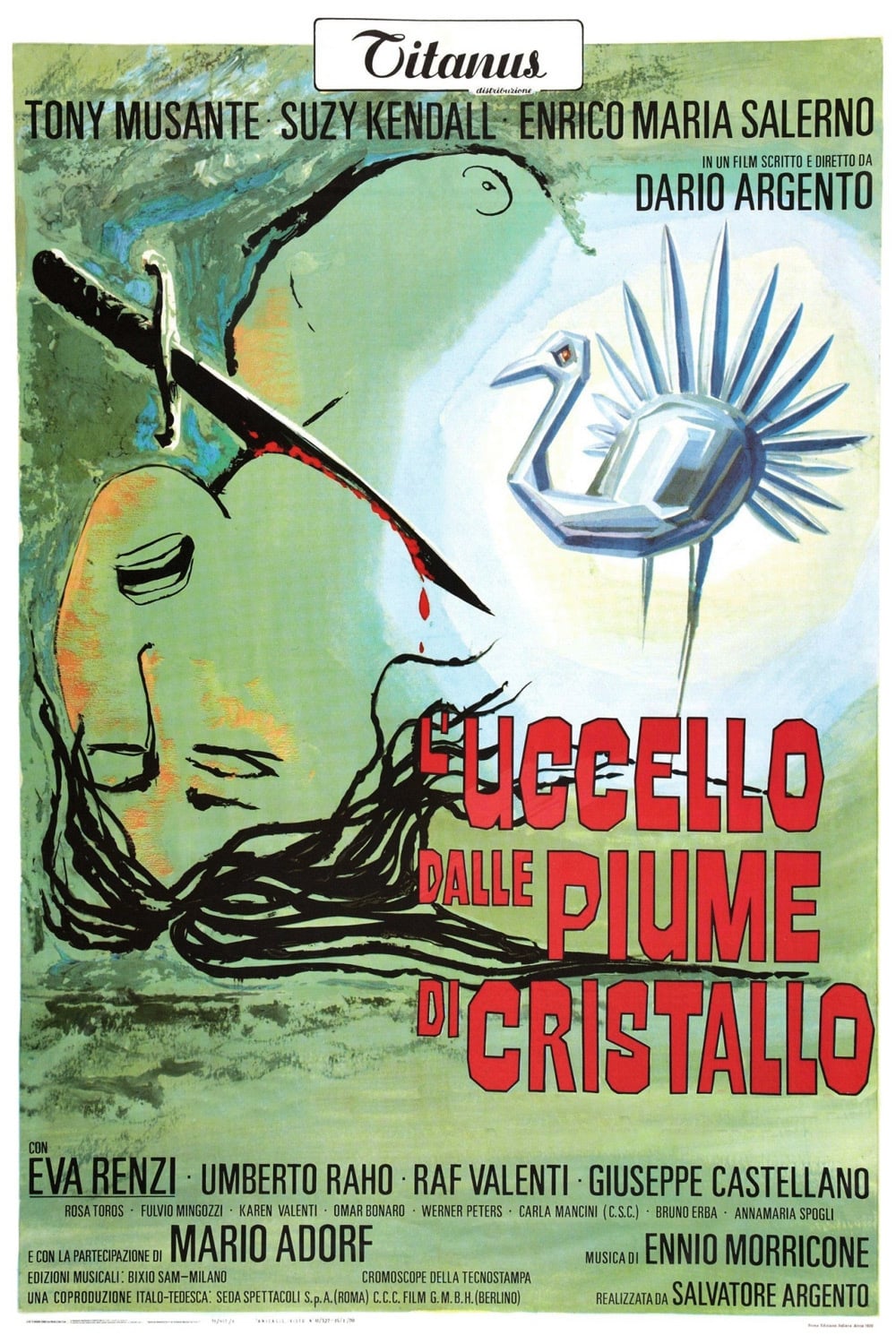

Having said that, it can be easily argued that the main historical importance of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage isn't its influence over a significant but ultimately obscure subset of mystery thrillers. It was also the directorial debut of a 29-year-old screenwriter named Dario Argento, primarily known for his Westerns at that time (including a story credit on a certain Once Upon a Time in the West), and that same Argento would develop over the following 15 years into perhaps the finest horror filmmaker known to cinema history, before spending the subsequent decades descending further into presumably unintentional self-parody.

But let us not permit foreknowledge of the dire 1998 version of The Phantom of the Opera to stand in the way of appreciating the director's first work, one of the most self-assured debuts of all time, a work so certain in its conception and execution that almost 40 years later I'd still quickly rank it as one of Argento's three finest pictures (alongside 1975's Deep Red and 1977's Suspiria). Though it perhaps lacks the quintessential baroque visual flair upon which the director's fame primarily rests, this is still a top-drawer murder mystery, all the more so given that unlike many gialli, and most of Argento's later films, it's actually pretty easy to follow all the details of the plot by the end, even if the "explanation" still comes down to "psychopaths kill people because they are psychopathic". And there's a perfectly fine compensation for anyone grousing that the fever-dream imagery of a Suspiria or Opera isn't anywhere to be found: in this his first movie, Argento collaborated for the only time with future superstar cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, mere months before he shot the indescribably magnificent The Conformist.

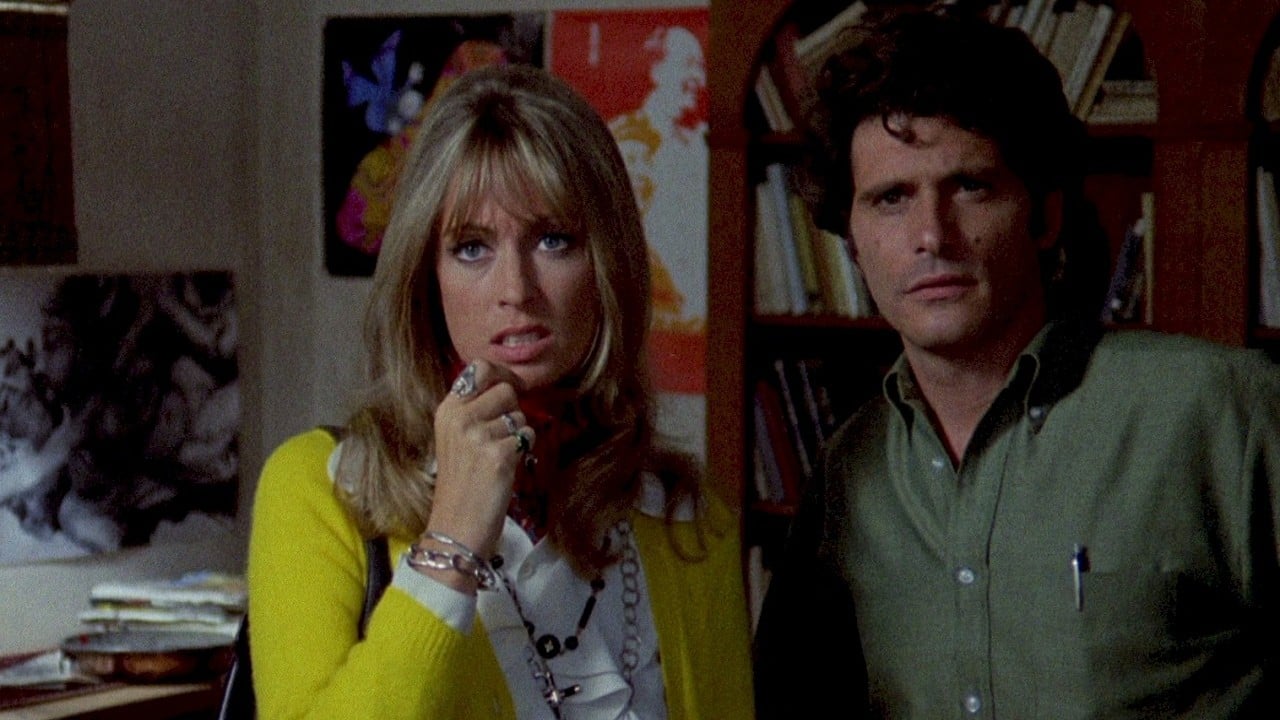

Like a great many gialli - indeed, like The Girl Who Knew Too Much - The Bird with the Crystal Plumage centers on the very unfortunate adventures which befall an American visiting Rome. In this case, our American is a novelist named Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante, an American actor who still works, and still makes Italian films from time to time), who is in Italy to write a manual on bird husbandry with professor Carlo Dover (Renato Romano, under the name "Raf Valenti") - novelists, like character actors, apparently need to take embarrassing jobs in Europe every now and then to pay the bills. The reason for Sam's trip aren't immediately important, though; what matters is that it's his last night in the country, and he's not really in the mood to become the key eyewitness to an extremely confusing murder attempt and therefore be held under direction of the Roman police from boarding his plane. Ah, but the best-laid schemes of mice and men gang aft agley - Sam does become the only eyewitness to an attempted stabbing, watching helplessly between electronically-controlled sliding glass doors as a woman struggles with a male figure in a black trenchcoat and black leather gloves on the top floor of a chic art gallery. That woman, Monica Ranieri (Eva Renzi) is the manager of the gallery, owned by her husband Alberto (Umberto Raho), and they're both very grateful that Sam's intervention saved her life, although they have no idea who would be trying to kill her or why; nor does the inspector in charge, Morosini (Enrico Maria Salerno), though he quickly assumes that it's part of a rash of seemingly unmotivated murders of isolated women that has so far claimed three lives and put Rome into a state of panic. Thus Sam - oh! inquisitive Yankee! - takes it upon himself to mount an amateur investigation, with the reluctant aid of his girlfriend Giulia (Suzy Kendall) and Carlo, while trying as hard as he might to remember a certain thing he knows that he saw, but just can't quite call it to memory now that he's in a pinch. "A pinch" meaning, primarily, that a man in a black trenchcoat is following him around the city, trying to kill him.

I think that gives us enough to work with, and I've only brought us about 15 minutes into the film. Certainly, that already shows some of the elements that had become cornerstones of gialli by then, and would become even more entrenched by their presence in this very movie: the black-gloved killer in a stylish trenchcoat, the outsider caught up in a confusing murder investigation (whether an American in Rome or a city-dweller in the country, gialli protagonists share a tendency to live far, far away from wherever it is that they find themselves hunting a murderer), intelligent and well-meaning police who are completely useless. And it boasts some of the trademarks that would crop up again and again in Argento's films: the hero is a writer, and the most important clue to the whole murder is something he has locked inside his memory, unable to consciously recall it. As the investigation proceeds, every clue leads to a dead end or another clue, but for the most part, nobody has figured out anything especially useful right up to the point where the killer is revealed. You could not hope for a more perfect example of a classic giallo except in one important respect: compared to the bloodthirsty films that succeeded it, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is a remarkably gore-free movie, even in the Blue Underground DVD and Blu-Ray that restores every known bit of violent footage: there are none of the amazingly esoteric killings with sprawling pools of blood that the genre became infamous for.

I dearly hope that's not a disappointment for anyone; sure, Argento does gore as well as anyone, but he's no one-trick pony, and there are more than enough reasons to admire what he's done in this film without having to resort to his sturdy command of Grand Guignol. This is an immaculately-filmed thriller, with individual moments that fully equal the work of Alfred Hitchcock (Argento's ultimate influence, as he was imitating a Hitchcock imitator). To pluck one moment out that works especially well, though not by any means the single best moment in the film: there comes a time when Sam has been sent on thin grounds to look for help in an old shack. In medium and wide shots, very under-lit, we see him look around to no avail, leading to a brilliant shot of Sam walking away from an open closet door (the camera pointing out from the closet), with his movements dislodging an arm that is attached to a body apparently stuffed in the top of the closet. In one shot, then, we have a close-up of the arm in the foreground, with Sam in the background, and it's both shocking and suspenseful - suspenseful because Sam doesn't notice it. So we get a few more shots of him puttering around, until the scene's corker of a visual climax: the camera moves in close to Sam's body, following him as he walks, stopping when he stops, dead in the middle of the frame, and then he steps to the side - revealing the dead body in the closet. It's immaculate choreography, that's what, and just to make everything all the more creepy, Argento has the actor playing the corpse stare directly in the camera no matter where the camera is located, which gives the altogether eerie feeling that hsi eyes are following us (this is all done in cutting, not camera movement, so the dead man's eyes never literally move).

That is a brilliantly-constructed scene, no two ways about it, and speaks to an innate gift for visual storytelling. Whether that gift was Argento's or Storaro's, I can't ultimately say, but either way, it works perfectly, and it's not an isolated incident.

I mentioned, at least twice, that Bird lacks Argento's more famous visionary style, but this is the sort of thing it has in its place: impeccable moments of suspense, and a genius's use of a roving camera - I cannot say to a certainty, but I think this may have more tracking shots than any other Argento film. The film has a more extensive use of the "killer's POV" shot than I can think of in any earlier film, and some very ambitious POV shots we get, including a "throw the camera out the window" shot that beats Stanley Kubrick's similar trick in A Clockwork Orange by a year.

Of course, Argento's visionary style was the stuff of impressionistic nightmares, and his first film was still firmly a murder mystery: the overlap between gialli and horror hadn't been made yet, the single element of the genre's ultimate profile that isn't present in Bird. That is to say, there'd have been no space for his horrific imagery, but plenty of room for suspense, in the form of careful editing or tracking shots or anything else. And as murder mysteries go, there isn't much room for improvement; some of his and others' later films might have been more "mature" examples of the same basic material, but Bird has its own kind of elemental perfection that makes it arguable the best introduction anyone could have to the world of the giallo.

Body Count: 5, I'm pretty sure, with three more that we only see in police file photos, but I might have missed one; like I said before, these earlier gialli aren't really body count movies, so the deaths aren't given quite as much narrative prominence as they are in any given slasher.

Tonight, then, we shall consider the Friday the 13th of the gialli.

Having said that, it can be easily argued that the main historical importance of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage isn't its influence over a significant but ultimately obscure subset of mystery thrillers. It was also the directorial debut of a 29-year-old screenwriter named Dario Argento, primarily known for his Westerns at that time (including a story credit on a certain Once Upon a Time in the West), and that same Argento would develop over the following 15 years into perhaps the finest horror filmmaker known to cinema history, before spending the subsequent decades descending further into presumably unintentional self-parody.

But let us not permit foreknowledge of the dire 1998 version of The Phantom of the Opera to stand in the way of appreciating the director's first work, one of the most self-assured debuts of all time, a work so certain in its conception and execution that almost 40 years later I'd still quickly rank it as one of Argento's three finest pictures (alongside 1975's Deep Red and 1977's Suspiria). Though it perhaps lacks the quintessential baroque visual flair upon which the director's fame primarily rests, this is still a top-drawer murder mystery, all the more so given that unlike many gialli, and most of Argento's later films, it's actually pretty easy to follow all the details of the plot by the end, even if the "explanation" still comes down to "psychopaths kill people because they are psychopathic". And there's a perfectly fine compensation for anyone grousing that the fever-dream imagery of a Suspiria or Opera isn't anywhere to be found: in this his first movie, Argento collaborated for the only time with future superstar cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, mere months before he shot the indescribably magnificent The Conformist.

Like a great many gialli - indeed, like The Girl Who Knew Too Much - The Bird with the Crystal Plumage centers on the very unfortunate adventures which befall an American visiting Rome. In this case, our American is a novelist named Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante, an American actor who still works, and still makes Italian films from time to time), who is in Italy to write a manual on bird husbandry with professor Carlo Dover (Renato Romano, under the name "Raf Valenti") - novelists, like character actors, apparently need to take embarrassing jobs in Europe every now and then to pay the bills. The reason for Sam's trip aren't immediately important, though; what matters is that it's his last night in the country, and he's not really in the mood to become the key eyewitness to an extremely confusing murder attempt and therefore be held under direction of the Roman police from boarding his plane. Ah, but the best-laid schemes of mice and men gang aft agley - Sam does become the only eyewitness to an attempted stabbing, watching helplessly between electronically-controlled sliding glass doors as a woman struggles with a male figure in a black trenchcoat and black leather gloves on the top floor of a chic art gallery. That woman, Monica Ranieri (Eva Renzi) is the manager of the gallery, owned by her husband Alberto (Umberto Raho), and they're both very grateful that Sam's intervention saved her life, although they have no idea who would be trying to kill her or why; nor does the inspector in charge, Morosini (Enrico Maria Salerno), though he quickly assumes that it's part of a rash of seemingly unmotivated murders of isolated women that has so far claimed three lives and put Rome into a state of panic. Thus Sam - oh! inquisitive Yankee! - takes it upon himself to mount an amateur investigation, with the reluctant aid of his girlfriend Giulia (Suzy Kendall) and Carlo, while trying as hard as he might to remember a certain thing he knows that he saw, but just can't quite call it to memory now that he's in a pinch. "A pinch" meaning, primarily, that a man in a black trenchcoat is following him around the city, trying to kill him.

I think that gives us enough to work with, and I've only brought us about 15 minutes into the film. Certainly, that already shows some of the elements that had become cornerstones of gialli by then, and would become even more entrenched by their presence in this very movie: the black-gloved killer in a stylish trenchcoat, the outsider caught up in a confusing murder investigation (whether an American in Rome or a city-dweller in the country, gialli protagonists share a tendency to live far, far away from wherever it is that they find themselves hunting a murderer), intelligent and well-meaning police who are completely useless. And it boasts some of the trademarks that would crop up again and again in Argento's films: the hero is a writer, and the most important clue to the whole murder is something he has locked inside his memory, unable to consciously recall it. As the investigation proceeds, every clue leads to a dead end or another clue, but for the most part, nobody has figured out anything especially useful right up to the point where the killer is revealed. You could not hope for a more perfect example of a classic giallo except in one important respect: compared to the bloodthirsty films that succeeded it, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is a remarkably gore-free movie, even in the Blue Underground DVD and Blu-Ray that restores every known bit of violent footage: there are none of the amazingly esoteric killings with sprawling pools of blood that the genre became infamous for.

I dearly hope that's not a disappointment for anyone; sure, Argento does gore as well as anyone, but he's no one-trick pony, and there are more than enough reasons to admire what he's done in this film without having to resort to his sturdy command of Grand Guignol. This is an immaculately-filmed thriller, with individual moments that fully equal the work of Alfred Hitchcock (Argento's ultimate influence, as he was imitating a Hitchcock imitator). To pluck one moment out that works especially well, though not by any means the single best moment in the film: there comes a time when Sam has been sent on thin grounds to look for help in an old shack. In medium and wide shots, very under-lit, we see him look around to no avail, leading to a brilliant shot of Sam walking away from an open closet door (the camera pointing out from the closet), with his movements dislodging an arm that is attached to a body apparently stuffed in the top of the closet. In one shot, then, we have a close-up of the arm in the foreground, with Sam in the background, and it's both shocking and suspenseful - suspenseful because Sam doesn't notice it. So we get a few more shots of him puttering around, until the scene's corker of a visual climax: the camera moves in close to Sam's body, following him as he walks, stopping when he stops, dead in the middle of the frame, and then he steps to the side - revealing the dead body in the closet. It's immaculate choreography, that's what, and just to make everything all the more creepy, Argento has the actor playing the corpse stare directly in the camera no matter where the camera is located, which gives the altogether eerie feeling that hsi eyes are following us (this is all done in cutting, not camera movement, so the dead man's eyes never literally move).

That is a brilliantly-constructed scene, no two ways about it, and speaks to an innate gift for visual storytelling. Whether that gift was Argento's or Storaro's, I can't ultimately say, but either way, it works perfectly, and it's not an isolated incident.

I mentioned, at least twice, that Bird lacks Argento's more famous visionary style, but this is the sort of thing it has in its place: impeccable moments of suspense, and a genius's use of a roving camera - I cannot say to a certainty, but I think this may have more tracking shots than any other Argento film. The film has a more extensive use of the "killer's POV" shot than I can think of in any earlier film, and some very ambitious POV shots we get, including a "throw the camera out the window" shot that beats Stanley Kubrick's similar trick in A Clockwork Orange by a year.

Of course, Argento's visionary style was the stuff of impressionistic nightmares, and his first film was still firmly a murder mystery: the overlap between gialli and horror hadn't been made yet, the single element of the genre's ultimate profile that isn't present in Bird. That is to say, there'd have been no space for his horrific imagery, but plenty of room for suspense, in the form of careful editing or tracking shots or anything else. And as murder mysteries go, there isn't much room for improvement; some of his and others' later films might have been more "mature" examples of the same basic material, but Bird has its own kind of elemental perfection that makes it arguable the best introduction anyone could have to the world of the giallo.

Body Count: 5, I'm pretty sure, with three more that we only see in police file photos, but I might have missed one; like I said before, these earlier gialli aren't really body count movies, so the deaths aren't given quite as much narrative prominence as they are in any given slasher.

Categories: crime pictures, dario argento, gialli, italian cinema, mysteries, summer of blood, thrillers