Bursting with excitement

Star Wars is typically held to have ruined American movies, by turning Hollywood's eye away from the narratively and structurally complex, character-driven films that dominated the 1970s, in favor of big, loud, effects-driven epics that all start to look a whole lot like one another once you've seen enough of them. And when you put it that way, sure, it seems pretty damn awful.

But there's a good side to it, too, which is that it inspired a lot of films by a lot of smart and gifted filmmakers that would otherwise have failed entirely to secure the money they needed to work. In otherwords it's thanks to Star Wars that we have "B-pictures with A-picture budgets", in the phrase that has been used to describe Raiders of the Lost Ark, which is a perfect example of what I'm talking about.

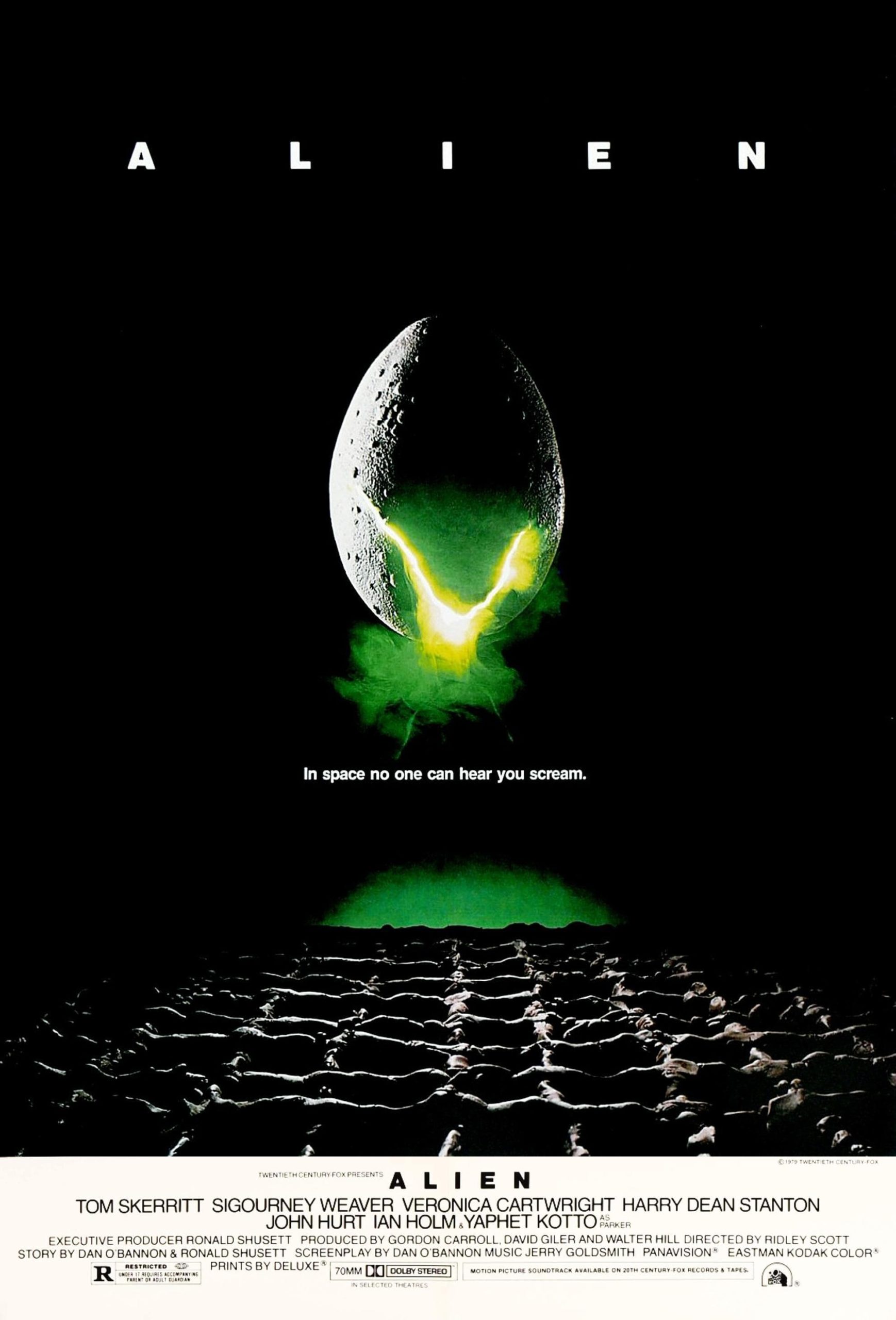

Here is another example: can you think of a movie in which the crew of a spaceship lands on a mysterious planet, finds a strange alien organism while exploring, and proceed to be horribly killed? You had damn well better, because that movie was made a shitload of times. But only once was it made two years after Star Wars, with a healthy studio budget and an extraterrestrial beast designed by one of the few true visionaries to ever sell his ideas to Hollywood, and that film, of course, is Alien, screenwriter Dan O'Bannon's riff on John W. Campbell Jr's Who Goes There?, which had previously been turned into The Thing from Another World, subsequently remade as the finest of all Alien rip-offs, The Thing, directed by John Carpenter, whose debut feature Dark Star was co-written by none other than Dan O'Bannon, and the green grass grew all around and around, and the green grass grew all around.

The point is: if Star Wars hadn't killed grown-up filmmaking, we wouldn't have an Alien, and that is a trade-off that I'm fine making, on account of Alien being a brilliant movie: one of the best horror movies ever made, and one of the most important pieces of design - and I refer not just to H.R. Giger's once-in-a-lifetime monster design, but to the remarkable spaceship interiors created by production designer Michael Seymour and art directors Roger Christian and Les Dilley, and set decorator Ian Whittaker, a miraculous used future setting that is one of the few out-and-out masterpieces of design in science-fiction filmmaking - and if that means that Robert Altman has to spend a decade in the wilderness, well heck, it's not like McCabe & Mrs. Miller just up and stopped existing.

But back to Alien. A film in two parts, almost equally long (the theatrical cut is 116 minutes, and The Scene that divides the film in two starts 55 minutes in), with as elegant and basic a storyline as you could hope for: there is a vessel in deep space, the Nostromo (what, if any relationship this has to Joseph Conrad's 1904 novel of the same name, I cannot say). She's returning to earth with a massive load of ore being refined on the ship's massive industrial rig - the actual habitable part of the Nostromo is so small as to be lost in the midst of a huge tangle of metal points looking like some unfathomably large oil rig in space. We spend a good deal of time wandering down the halls of the ship, looking at the various monitors and displays, until one of them starts blinking red; this is apparently enough to wake up the crew from their cryogenic beds: Captain Dallas (Tom Skerrit), second-in-command Kane (John Hurt), warrant officer Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), navigator Lambert (Veronica Cartwright), science officer Ash (Ian Holm), engineer Parker (Yaphet Kotto), and his assistant Brett (Harry Dean Stanton). They've received a distress signal from a nearby planet, and the charter of the company that hired them (always, ominously, referred to just like that: "The Company") demands that they land and investigate. This ends poorly.

Forgive the brief synopsis, but really, isn't Alien one of those movies we all kind of know about, even if we haven't seen it? The roomful of leathery eggs beneath a massive dead alien with an exploded chest, the hideous, insect-like being that attaches itself to Kane, a profoundly unsuccessful dinner follows, and then everybody in the crew is killed by a hideous creature, Ten Little Indians style. I've mentioned before and will undoubtedly mention again, that Alien is rather exactly like a slasher movie, a whole year before that genre started booming and with almost all of the worst elements of the slasher forcibly removed by making the cast adults in a huge long-haul space truck. It's all there, though: a first half that is deliberately slow and even "boring", though I don't care for that word's context in this case; characters who have no more personality than the one adjective or maybe two (we're very accustomed to thinking of Ripley as some kind of miraculously deep heroine, but that's almost entirely because of Aliens), a Final Girl sequence, a twisty "it's not dead yet!" ending.

With the important caveat that all of these things are done extremely well, and with rather more purpose than slasher films tend to bother with. The characters, for example, aren't given much definition because that's not who they are and why they're there: the Nostromo is a grubby, working ship, and these people are not there to have introspective conversations with one another - it seems quite clear that nobody here regards anyone else as their "friend", just as their co-worker - but to get a job done. They're grunts and regular folks, and that is what makes the arrival of the alien far more terrifying; after which point everybody is too concerned with survival to do much introspecting, anyway.

Alien is a machine, ultimately: and undoubtedly, you could figure out how to make that a criticism, but that's the furthest from my intent. Because it's an outstandingly well-built machine. Director Ridley Scott had made but a single feature, the Napoleonic adventure The Duellists, prior to Alien, but this sophomore effort does not seem in even the tiniest degree like a learning-curve project: it is self-assured to the point of being just plain obnoxious, and even now, more than 30 decades later, most of his reputation as a filmmaker still rests on just how incredibly good this movie, and his next project, turned out. There's really not a single flaw in it; okay, a single flaw, which is the transition from a prop head to an actor's head late in the movie, done in a terrible jump cut that isn't even necessary. But other than that, Scott's manipulation of this material is absolutely flawless: the inside of the Nostromo is shot using such flat, cramped angles that it seems suffocating and claustrophic long before the addition of the alien makes that claustrophobia so undenurable; his reckless dependence on close-ups of the actors emphasises both their own stress and limits our POV to their own; and for that matter, POV is a huge part of why this film works in the lengthy stretch where the whole point of the movie is that there's something terrifying out there, and there are far too many places on board where it can hide. Scott and his cinematographer, Derek Vanlint, make very nearly the best use of underlit interiors a horror film could, and even better, all of that darkness is completely motivated by the setting; and so we get what amounts to an expressionist haunted house movie set inside a science-fiction film of almost unprecedented physical realism.

And plenty of credit has to go to the editing, and the sound design, and Jerry Goldsmith's absolutely fantastic score, tonally unsettling and thoroughly discomfiting, perhaps the best thing - and certainly the most ambitious - outside of his work on Planet of the Apes. One need merely pay just a slight bit of attention to the opening credits, Goldsmith's menacing hum on the soundtrack, to understand how much of the mood of the film is generated from his music, and really, from the use of sound on the whole.

But for all that this is a collaborative affair, and it couldn't have worked without those great sets, and Scott's perfect direction, and a remarkable cast led by Weaver in an effortlessly authoritative, commanding performance giving real credibility to these deliberately under-developed characters, and Goldsmith's score, and everything - again I say, without even one of these things, Alien would be less of a movie - but it all really comes down to Giger's alien design. A far worse movie in every respect could still have become a beloved classic with that design. Need I even bother reminding you? The shiny carapace, like a beetle; the heavily sexual details like the chomping penis-mouth, or the vagina-spider horror of the embryonic form of the creature; the odd bits pointing where they simply have no cause to; and the conspicuous lack of eyes. There's really nothing even comparable to it in the 90-ish years of cinema preceding Alien, and while the film's success caused God knows how many imitators, none of them work at this level. Simply put, the alien is a nightmare that also seems completely plausible, both as a physical object and as a life-form with a remarkably different biology than our own; but not a fantastic biology, and that matters. It says something that, for all that Scott and Vanlint make certain to keep the creature limited to flashes and pieces for most of the movie, it never stops being convincing even as we see more and more of it. Name another movie monster for which that's true. And that speaks to the quality, not of how "scary" the thing is - I have to confess that I've never actually found Alien to be a particularly scary movie, not even in my less-jaded youth - but to how fleshy and solid and real it is, a terror from hell to match the the grounded, hugely prosaic future world presented by the rest of the movie.

I don't know that calling Alien a triumph of cinematic realism is a particularly smart move on my point, but that's basically what it all adds up to: people who seem pretty much exactly like people moving in a space that's too ugly and awkward not to feel authentic, encountering a very present and tangible if completely unrelatable avatar of death. As science-fiction, Alien goes absolutely as far out of its way as possible not to indulge in anything ridiculous, and that's why it works so damn well as horror: the genre is all about something dangerous and perverted violating a normal situation, and when that can be done so very well in such a widly inventive setting as deep space; that's alchemy, is what that is, and in a century of sci-fi/horror hybrids, few if any movies do such a good job at reaching the absolute highest peaks of both halves of that equation as this one; it is one of the all-time unqualified masterpieces of genre experimentation and one of the best American films of the '70s, New Hollywood Cinema be damned.

Reviews in this series

Alien (Scott, 1979)

Aliens (Cameron, 1986)

Alien³ (Fincher, 1992)

Alien Resurrection (Jeunet, 1997)

Alien vs. Predator (Anderson, 2004)

Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (The Brothers Strause, 2007)

Prometheus (Scott, 2012)

Alien: Covenant (Scott, 2017)

But there's a good side to it, too, which is that it inspired a lot of films by a lot of smart and gifted filmmakers that would otherwise have failed entirely to secure the money they needed to work. In otherwords it's thanks to Star Wars that we have "B-pictures with A-picture budgets", in the phrase that has been used to describe Raiders of the Lost Ark, which is a perfect example of what I'm talking about.

Here is another example: can you think of a movie in which the crew of a spaceship lands on a mysterious planet, finds a strange alien organism while exploring, and proceed to be horribly killed? You had damn well better, because that movie was made a shitload of times. But only once was it made two years after Star Wars, with a healthy studio budget and an extraterrestrial beast designed by one of the few true visionaries to ever sell his ideas to Hollywood, and that film, of course, is Alien, screenwriter Dan O'Bannon's riff on John W. Campbell Jr's Who Goes There?, which had previously been turned into The Thing from Another World, subsequently remade as the finest of all Alien rip-offs, The Thing, directed by John Carpenter, whose debut feature Dark Star was co-written by none other than Dan O'Bannon, and the green grass grew all around and around, and the green grass grew all around.

The point is: if Star Wars hadn't killed grown-up filmmaking, we wouldn't have an Alien, and that is a trade-off that I'm fine making, on account of Alien being a brilliant movie: one of the best horror movies ever made, and one of the most important pieces of design - and I refer not just to H.R. Giger's once-in-a-lifetime monster design, but to the remarkable spaceship interiors created by production designer Michael Seymour and art directors Roger Christian and Les Dilley, and set decorator Ian Whittaker, a miraculous used future setting that is one of the few out-and-out masterpieces of design in science-fiction filmmaking - and if that means that Robert Altman has to spend a decade in the wilderness, well heck, it's not like McCabe & Mrs. Miller just up and stopped existing.

But back to Alien. A film in two parts, almost equally long (the theatrical cut is 116 minutes, and The Scene that divides the film in two starts 55 minutes in), with as elegant and basic a storyline as you could hope for: there is a vessel in deep space, the Nostromo (what, if any relationship this has to Joseph Conrad's 1904 novel of the same name, I cannot say). She's returning to earth with a massive load of ore being refined on the ship's massive industrial rig - the actual habitable part of the Nostromo is so small as to be lost in the midst of a huge tangle of metal points looking like some unfathomably large oil rig in space. We spend a good deal of time wandering down the halls of the ship, looking at the various monitors and displays, until one of them starts blinking red; this is apparently enough to wake up the crew from their cryogenic beds: Captain Dallas (Tom Skerrit), second-in-command Kane (John Hurt), warrant officer Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), navigator Lambert (Veronica Cartwright), science officer Ash (Ian Holm), engineer Parker (Yaphet Kotto), and his assistant Brett (Harry Dean Stanton). They've received a distress signal from a nearby planet, and the charter of the company that hired them (always, ominously, referred to just like that: "The Company") demands that they land and investigate. This ends poorly.

Forgive the brief synopsis, but really, isn't Alien one of those movies we all kind of know about, even if we haven't seen it? The roomful of leathery eggs beneath a massive dead alien with an exploded chest, the hideous, insect-like being that attaches itself to Kane, a profoundly unsuccessful dinner follows, and then everybody in the crew is killed by a hideous creature, Ten Little Indians style. I've mentioned before and will undoubtedly mention again, that Alien is rather exactly like a slasher movie, a whole year before that genre started booming and with almost all of the worst elements of the slasher forcibly removed by making the cast adults in a huge long-haul space truck. It's all there, though: a first half that is deliberately slow and even "boring", though I don't care for that word's context in this case; characters who have no more personality than the one adjective or maybe two (we're very accustomed to thinking of Ripley as some kind of miraculously deep heroine, but that's almost entirely because of Aliens), a Final Girl sequence, a twisty "it's not dead yet!" ending.

With the important caveat that all of these things are done extremely well, and with rather more purpose than slasher films tend to bother with. The characters, for example, aren't given much definition because that's not who they are and why they're there: the Nostromo is a grubby, working ship, and these people are not there to have introspective conversations with one another - it seems quite clear that nobody here regards anyone else as their "friend", just as their co-worker - but to get a job done. They're grunts and regular folks, and that is what makes the arrival of the alien far more terrifying; after which point everybody is too concerned with survival to do much introspecting, anyway.

Alien is a machine, ultimately: and undoubtedly, you could figure out how to make that a criticism, but that's the furthest from my intent. Because it's an outstandingly well-built machine. Director Ridley Scott had made but a single feature, the Napoleonic adventure The Duellists, prior to Alien, but this sophomore effort does not seem in even the tiniest degree like a learning-curve project: it is self-assured to the point of being just plain obnoxious, and even now, more than 30 decades later, most of his reputation as a filmmaker still rests on just how incredibly good this movie, and his next project, turned out. There's really not a single flaw in it; okay, a single flaw, which is the transition from a prop head to an actor's head late in the movie, done in a terrible jump cut that isn't even necessary. But other than that, Scott's manipulation of this material is absolutely flawless: the inside of the Nostromo is shot using such flat, cramped angles that it seems suffocating and claustrophic long before the addition of the alien makes that claustrophobia so undenurable; his reckless dependence on close-ups of the actors emphasises both their own stress and limits our POV to their own; and for that matter, POV is a huge part of why this film works in the lengthy stretch where the whole point of the movie is that there's something terrifying out there, and there are far too many places on board where it can hide. Scott and his cinematographer, Derek Vanlint, make very nearly the best use of underlit interiors a horror film could, and even better, all of that darkness is completely motivated by the setting; and so we get what amounts to an expressionist haunted house movie set inside a science-fiction film of almost unprecedented physical realism.

And plenty of credit has to go to the editing, and the sound design, and Jerry Goldsmith's absolutely fantastic score, tonally unsettling and thoroughly discomfiting, perhaps the best thing - and certainly the most ambitious - outside of his work on Planet of the Apes. One need merely pay just a slight bit of attention to the opening credits, Goldsmith's menacing hum on the soundtrack, to understand how much of the mood of the film is generated from his music, and really, from the use of sound on the whole.

But for all that this is a collaborative affair, and it couldn't have worked without those great sets, and Scott's perfect direction, and a remarkable cast led by Weaver in an effortlessly authoritative, commanding performance giving real credibility to these deliberately under-developed characters, and Goldsmith's score, and everything - again I say, without even one of these things, Alien would be less of a movie - but it all really comes down to Giger's alien design. A far worse movie in every respect could still have become a beloved classic with that design. Need I even bother reminding you? The shiny carapace, like a beetle; the heavily sexual details like the chomping penis-mouth, or the vagina-spider horror of the embryonic form of the creature; the odd bits pointing where they simply have no cause to; and the conspicuous lack of eyes. There's really nothing even comparable to it in the 90-ish years of cinema preceding Alien, and while the film's success caused God knows how many imitators, none of them work at this level. Simply put, the alien is a nightmare that also seems completely plausible, both as a physical object and as a life-form with a remarkably different biology than our own; but not a fantastic biology, and that matters. It says something that, for all that Scott and Vanlint make certain to keep the creature limited to flashes and pieces for most of the movie, it never stops being convincing even as we see more and more of it. Name another movie monster for which that's true. And that speaks to the quality, not of how "scary" the thing is - I have to confess that I've never actually found Alien to be a particularly scary movie, not even in my less-jaded youth - but to how fleshy and solid and real it is, a terror from hell to match the the grounded, hugely prosaic future world presented by the rest of the movie.

I don't know that calling Alien a triumph of cinematic realism is a particularly smart move on my point, but that's basically what it all adds up to: people who seem pretty much exactly like people moving in a space that's too ugly and awkward not to feel authentic, encountering a very present and tangible if completely unrelatable avatar of death. As science-fiction, Alien goes absolutely as far out of its way as possible not to indulge in anything ridiculous, and that's why it works so damn well as horror: the genre is all about something dangerous and perverted violating a normal situation, and when that can be done so very well in such a widly inventive setting as deep space; that's alchemy, is what that is, and in a century of sci-fi/horror hybrids, few if any movies do such a good job at reaching the absolute highest peaks of both halves of that equation as this one; it is one of the all-time unqualified masterpieces of genre experimentation and one of the best American films of the '70s, New Hollywood Cinema be damned.

Reviews in this series

Alien (Scott, 1979)

Aliens (Cameron, 1986)

Alien³ (Fincher, 1992)

Alien Resurrection (Jeunet, 1997)

Alien vs. Predator (Anderson, 2004)

Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (The Brothers Strause, 2007)

Prometheus (Scott, 2012)

Alien: Covenant (Scott, 2017)