Snakes alive!

Anaconda begins with a text crawl so deliriously full of bullshit that I cannot possibly resist quoting it in full:

The film is one of the highlights of what looks, over two decades later, like the last Golden Age of so-bad-it's-good cinema. Monster movies were a particular beneficiary of this moment in history: I imagine this is probably thanks to the gargantuan success of Jurassic Park in 1993, which modeled a way of marrying animatronics with the new-fangled toy of CGI, and re-ignited the audience's taste for old-school adventure tales of man versus toothy beast. Add in the brief flourishing of environmentalism at the start of the decade, and the particular character of those creatures features - all about the danger of humans mucking about in untouched corners of the world and damaging animals, maybe set in the rain forest if you're feeling especially straightforward - starts to calcify. And thus it is in 1997 that we arrive at this most '90s of bad genre films, its period specificity surpassed maybe only by the magnificent decade-capping Deep Blue Sea, which adds genetic engineering and Samuel L. Jackson to the mix.

The film starts us out by revealing one of the many, many stupid habits it will be unable to break over the next hour and a half, with a scene of a poacher (Danny Trejo, who was big enough by this point that I imagine this counts as a "cameo" and not just a "small role") on a boat in the Amazon being menaced by an unseen something that bursts through the floorboards. Rather than be devoured by the thing, the poacher shoots himself, which is meant to be our first sign that whatever this ferocious 40-foot regurgitating nightmare is, death itself is preferable. But all I could think was: it bursts through the floorboards? How? And this is where we learn, nice and early, that director Luis Llosa and screenwriters Hans Bauer and Jim Cash & Jack Epps, Jr. think that anacondas are basically sharks. This is going to persist throughout the movie, you understand. At one point, the anaconda's presence is marked by the displacement of so much water that it causes two-foot waves to bob up and down. Later on, a pool of blood is used as bait. Which, to be fair, you can bait most predators with blood, but the implication is clearly that you need chum to catch an anaconda, which contradicts things we've already seen. To continue being fair, Llosa makes the most of this: he has had the good sense to realise, as surprisingly few '90s directors did, that when you're making a giant killer animal movie, you can't really do better than to copy as much as you can from Jaws, and most of the unironically good moments in Anaconda are the ones where he's directly copying shots, or at least ideas for shots, including a dolly-zoom shot that exactly mimics the very famous one of Roy Scheider. And the screenwriters seem to have thought of this too, given that this film's villain is basically Evil Quint.

The bulk of the film consists of the misadventures of a documentary film crew, plunging into the deep Amazon to find a lost tribe called the Shirishama. The head of this quest is Terri Flores (Jennifer Lopez), a recent film school graduate making her first professional project, helped out by her childhood friend Danny (Ice Cube) as the cameraman, Denise (Kari Wuhrer) as all-purpose production staff, Denise's boyfriend Gary (Owen Wilson) as the sound recordist, and Dr. Steven Cale (Eric Stoltz) on board to help find the Shirishama; he's officially an anthropologist, but he also seems to somehow be Terri's advisor and lover. It's not clear. Really, though, if you took out Danny, you'd take out all indication that this is a film crew of any sort. To round out the cast, we get narrator Warren Westridge (Jonathan Hyde), because you need a stuffy Brit to huff and puff about these intolerable conditions in a genre film, and if that means having the narrator come along for the shoot, in defiance of any sane documentary practice, then so be it. Actually, I don't want to hate on Westridge too hard; he's honestly the focal point of some of the cleverest writing in the film. His character is initially a stock cartoon, but he also gets to shift to becoming genuinely useful and smart, and ultimately selfless, showcasing a level of sophisticated character writing that's simply not found elsewhere in this genre. Or elsewhere in this movie. Lastly, the boat is being piloted by Mateo (Vincent Castellanos), so we can have an actual South American character (though Castellanos is Cuban), and also a first victim who won't have so much personality that we'll be troubled by his death.

Looks like everybody, right? No, not yet - where's our untrustworthy local who claims to know more about the region and will guide the heroes to their goal, while secretly putting them in danger for his own benefit? They find him pretty early on, rescuing him from his own sinking boat, and he is a doozy. There's enough that's enjoyably stupid about Anaconda that I'd probably still like it more than the average '90s creature feature, but there's obviously one thing that pushes it front and center, and that is, no question about it, Paul Serone, the Paraguayan snake hunter looking for the enormous anacondas that were part of the Shirishamas' worship practices, or who knows what. He's played by Jon Voight, who leaves absolutely nothing on the table, including things he definitely should have. It's a performance made out of four interlocking pieces. First, the remarkably ill-advised ponytail. Second, the mouth, which is always slightly agape, so you always see his top teeth peering between his lips; it puts his face in a perpetual look of sour disbelief, like he spends the whole movie smelling something nasty, but not enough to mention it. Third, his eyes, which he keeps locked in a squint, even when he's opening them really wide. I don't know how to explain it - it's a paradox. There he is, bugging his eyes out in Ahab-like mania, and he's still squinting menacingly.

Fourth, finally, and beyond question best of all - The Accent. I pray to God that Voight didn't think that's what people from Paraguay sound like. I don't think anybody from anywhere sounds like that. It's a combination of mumbling, whining, and something has a vaguely Spanish inflection, but only less vague than it is, say, Creole, or New Jersey Italian. Imagine Mel Blanc doing Pepe Le Pew as Edward James Olmos playing Don Corleone. That's terrible, but I can't even figure out how to describe it, and I've been trying for 23 years. Coupled with his weird refusal to ever allow his lips to meet, and Voight's line deliveries are, every single last one of them, the most baffling, hilariously campy thing you could possibly imagine encountering. It is, by my reckoning, an all-time Bad Acting Hall of Fame performance, deprived of its properly iconic status I suspect because it is exceedingly difficult to properly mimic. Which I have also been trying to do for 23 years.

At any rate, once Serone is onboard, Anaconda becomes a kitschy, campy hoot. The dialogue is full of ominous portendings, including a lingering description of the catfish that swims up your dick and lodges there with spikes which is somehow played as thriller foreshadowing rather than as gross-out comedy (unlike regurgitation, dick-catfish will not be making an appearance later in the movie). The filmmaking struggles to take advantage of Bill Butler's genuinely lovely location photography (he also shot Jaws, believe it or not), with Llosa never figuring out how to stage his actors around the boat to give us a good sense of how it's laid out; once Dr. Cale swallows a poisonous wasp and spends most of the rest of the movie in a coma, it's never even slightly clear how his sickroom relates to the rest of the cast. Randy Edelman's score keeps getting almost close to the correct tone, but generally has a "bigness" that makes it feel like the film is mugging, even as the non-Voight actors have a uniform tendency to play things too small and flat.

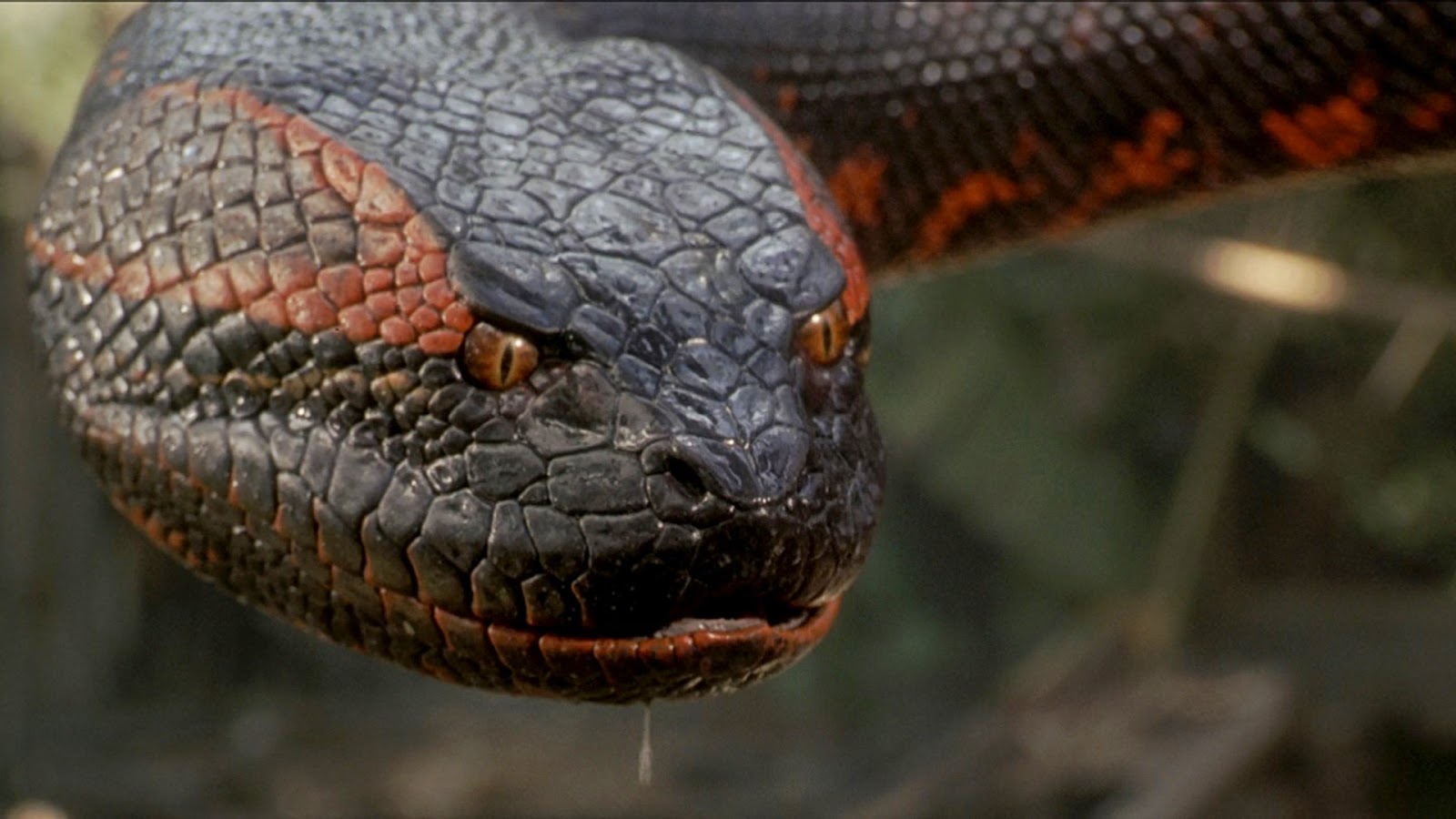

It's all worth it, though, for the moment about halfway through when we finally get to see the promised anaconda. The filmmakers know what we're here for, and as clumsy (and, to be sure, often hilariously over-articulated) dialogue scenes can be, the snake attacks are exactly what they need to be. With one great exception: the snake is played for a substantial amount of its running time by CGI that looked lousy in 1997 and looks no better now, with absolutely no hint of the thickness and weight that are an anaconda's most salient features. The CGI snake moves more like a pit viper than a constrictor, and it spins around people like they've been lassoed by a cartoon cowboy. But when it's a practical animatronic effect, mirabile dictu! The snake is the work of Walt Conti, whose work mostly consists of whales and sharks, but whose second and final snake(after the rattlesnakes in 1994's Maverick) is something truly to behold. It whips, it glides, it has unnecessarily thoughtful expressions, it knowingly threatens. And while Llosa only rarely gives it a good moment in the spotlight, he knows how to make it count; there's a moment where the snake slowly pushes into a cave behind a waterfall that is every bit as good as a nearly identical scene from The Lost World: Jurassic Park a few weeks later, and that was directed by Steven Spielberg himself.

Outside of the anaconda, Anaconda's pleasures are virtually all ironic, or at least campy: there's a good amount of spot-the-bad-filmmaking to be had including a moment where an unnecessary shot of a boat reversing course is fabricated by simply running the footage backwards, so that we see a waterfall going upwards. For, like, a full second. Later, there's a slow-motion shot of blood being splashed on Lopez that gives us a nice long look at how blood is not, in fact, being splashed on Lopez. And of course, Voight is a treasure trove of amazingly awful gems, from his threatening one-liners to his rhapsodising about baby snakes to his incomparable wink in the second-to-last shot where he appears in the whole movie. It's a thoroughly goofy movie, its saving grace; unlike many films in its genre, from this period or others, the meager attempts at sincerity and engagement with the plot are so flimsy that they don't bog the film down. Witness, for example, its ending, where we do meet the Shirishama, the mystically uplifting moment that the narrative was allegedly leading to, and the film's response is to find it so unambiguously boring that it races for the credits at top speed. It's not that it's knowing kitsch; Llosa's attempts to make the thriller scenes work demonstrates that. But it knows enough to stay out of the way of kitsch, and that's all it takes to make one of the most bubbly, top-to-bottom fun shitty movies of an entire generation.

Reviews in this series

Anaconda (Llosa, 1997)

Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid (Little, 2004)

Anaconda 3: Offspring (FauntLeRoy, 2008)

Anacondas: Trail of Blood (FauntLeRoy, 2009)

Lake Placid vs. Anaconda (Stone, 2015)

Tales of monstrous, man-eating Anacondas have been recounted for centuries by tribespeople of the Amazon Basin, some of whom are said to worship these giant snakes.It is not clear to me that anything in any of those three sentences is correct, including the capital B in "Basin". But that's hardly the point. The point is that we're here to watch a late-'90s creature feature, and feeding those lines to a B-movie fan is like throwing a big slab of raw beef into a school of piranhas. Especially that bit about regurgitation. Make an idle claim like that at the start of your movie and you've already won the rapt attention of every genre movie junkie who will happily wait through a nice trim running time (and at 89 minutes including credits, Anaconda might very well have the most correct running time of any movie ever made) to find out who, exactly, will be getting regurgitated and re-eaten.

Anacondas are among the most ferocious – and enormous – creatures on earth, growing, in certain cases, as long as 40 feet. Unique among snakes, they are not satisfied after eating a victim. They will regurgitate their prey in order to kill and eat again.

The film is one of the highlights of what looks, over two decades later, like the last Golden Age of so-bad-it's-good cinema. Monster movies were a particular beneficiary of this moment in history: I imagine this is probably thanks to the gargantuan success of Jurassic Park in 1993, which modeled a way of marrying animatronics with the new-fangled toy of CGI, and re-ignited the audience's taste for old-school adventure tales of man versus toothy beast. Add in the brief flourishing of environmentalism at the start of the decade, and the particular character of those creatures features - all about the danger of humans mucking about in untouched corners of the world and damaging animals, maybe set in the rain forest if you're feeling especially straightforward - starts to calcify. And thus it is in 1997 that we arrive at this most '90s of bad genre films, its period specificity surpassed maybe only by the magnificent decade-capping Deep Blue Sea, which adds genetic engineering and Samuel L. Jackson to the mix.

The film starts us out by revealing one of the many, many stupid habits it will be unable to break over the next hour and a half, with a scene of a poacher (Danny Trejo, who was big enough by this point that I imagine this counts as a "cameo" and not just a "small role") on a boat in the Amazon being menaced by an unseen something that bursts through the floorboards. Rather than be devoured by the thing, the poacher shoots himself, which is meant to be our first sign that whatever this ferocious 40-foot regurgitating nightmare is, death itself is preferable. But all I could think was: it bursts through the floorboards? How? And this is where we learn, nice and early, that director Luis Llosa and screenwriters Hans Bauer and Jim Cash & Jack Epps, Jr. think that anacondas are basically sharks. This is going to persist throughout the movie, you understand. At one point, the anaconda's presence is marked by the displacement of so much water that it causes two-foot waves to bob up and down. Later on, a pool of blood is used as bait. Which, to be fair, you can bait most predators with blood, but the implication is clearly that you need chum to catch an anaconda, which contradicts things we've already seen. To continue being fair, Llosa makes the most of this: he has had the good sense to realise, as surprisingly few '90s directors did, that when you're making a giant killer animal movie, you can't really do better than to copy as much as you can from Jaws, and most of the unironically good moments in Anaconda are the ones where he's directly copying shots, or at least ideas for shots, including a dolly-zoom shot that exactly mimics the very famous one of Roy Scheider. And the screenwriters seem to have thought of this too, given that this film's villain is basically Evil Quint.

The bulk of the film consists of the misadventures of a documentary film crew, plunging into the deep Amazon to find a lost tribe called the Shirishama. The head of this quest is Terri Flores (Jennifer Lopez), a recent film school graduate making her first professional project, helped out by her childhood friend Danny (Ice Cube) as the cameraman, Denise (Kari Wuhrer) as all-purpose production staff, Denise's boyfriend Gary (Owen Wilson) as the sound recordist, and Dr. Steven Cale (Eric Stoltz) on board to help find the Shirishama; he's officially an anthropologist, but he also seems to somehow be Terri's advisor and lover. It's not clear. Really, though, if you took out Danny, you'd take out all indication that this is a film crew of any sort. To round out the cast, we get narrator Warren Westridge (Jonathan Hyde), because you need a stuffy Brit to huff and puff about these intolerable conditions in a genre film, and if that means having the narrator come along for the shoot, in defiance of any sane documentary practice, then so be it. Actually, I don't want to hate on Westridge too hard; he's honestly the focal point of some of the cleverest writing in the film. His character is initially a stock cartoon, but he also gets to shift to becoming genuinely useful and smart, and ultimately selfless, showcasing a level of sophisticated character writing that's simply not found elsewhere in this genre. Or elsewhere in this movie. Lastly, the boat is being piloted by Mateo (Vincent Castellanos), so we can have an actual South American character (though Castellanos is Cuban), and also a first victim who won't have so much personality that we'll be troubled by his death.

Looks like everybody, right? No, not yet - where's our untrustworthy local who claims to know more about the region and will guide the heroes to their goal, while secretly putting them in danger for his own benefit? They find him pretty early on, rescuing him from his own sinking boat, and he is a doozy. There's enough that's enjoyably stupid about Anaconda that I'd probably still like it more than the average '90s creature feature, but there's obviously one thing that pushes it front and center, and that is, no question about it, Paul Serone, the Paraguayan snake hunter looking for the enormous anacondas that were part of the Shirishamas' worship practices, or who knows what. He's played by Jon Voight, who leaves absolutely nothing on the table, including things he definitely should have. It's a performance made out of four interlocking pieces. First, the remarkably ill-advised ponytail. Second, the mouth, which is always slightly agape, so you always see his top teeth peering between his lips; it puts his face in a perpetual look of sour disbelief, like he spends the whole movie smelling something nasty, but not enough to mention it. Third, his eyes, which he keeps locked in a squint, even when he's opening them really wide. I don't know how to explain it - it's a paradox. There he is, bugging his eyes out in Ahab-like mania, and he's still squinting menacingly.

Fourth, finally, and beyond question best of all - The Accent. I pray to God that Voight didn't think that's what people from Paraguay sound like. I don't think anybody from anywhere sounds like that. It's a combination of mumbling, whining, and something has a vaguely Spanish inflection, but only less vague than it is, say, Creole, or New Jersey Italian. Imagine Mel Blanc doing Pepe Le Pew as Edward James Olmos playing Don Corleone. That's terrible, but I can't even figure out how to describe it, and I've been trying for 23 years. Coupled with his weird refusal to ever allow his lips to meet, and Voight's line deliveries are, every single last one of them, the most baffling, hilariously campy thing you could possibly imagine encountering. It is, by my reckoning, an all-time Bad Acting Hall of Fame performance, deprived of its properly iconic status I suspect because it is exceedingly difficult to properly mimic. Which I have also been trying to do for 23 years.

At any rate, once Serone is onboard, Anaconda becomes a kitschy, campy hoot. The dialogue is full of ominous portendings, including a lingering description of the catfish that swims up your dick and lodges there with spikes which is somehow played as thriller foreshadowing rather than as gross-out comedy (unlike regurgitation, dick-catfish will not be making an appearance later in the movie). The filmmaking struggles to take advantage of Bill Butler's genuinely lovely location photography (he also shot Jaws, believe it or not), with Llosa never figuring out how to stage his actors around the boat to give us a good sense of how it's laid out; once Dr. Cale swallows a poisonous wasp and spends most of the rest of the movie in a coma, it's never even slightly clear how his sickroom relates to the rest of the cast. Randy Edelman's score keeps getting almost close to the correct tone, but generally has a "bigness" that makes it feel like the film is mugging, even as the non-Voight actors have a uniform tendency to play things too small and flat.

It's all worth it, though, for the moment about halfway through when we finally get to see the promised anaconda. The filmmakers know what we're here for, and as clumsy (and, to be sure, often hilariously over-articulated) dialogue scenes can be, the snake attacks are exactly what they need to be. With one great exception: the snake is played for a substantial amount of its running time by CGI that looked lousy in 1997 and looks no better now, with absolutely no hint of the thickness and weight that are an anaconda's most salient features. The CGI snake moves more like a pit viper than a constrictor, and it spins around people like they've been lassoed by a cartoon cowboy. But when it's a practical animatronic effect, mirabile dictu! The snake is the work of Walt Conti, whose work mostly consists of whales and sharks, but whose second and final snake(after the rattlesnakes in 1994's Maverick) is something truly to behold. It whips, it glides, it has unnecessarily thoughtful expressions, it knowingly threatens. And while Llosa only rarely gives it a good moment in the spotlight, he knows how to make it count; there's a moment where the snake slowly pushes into a cave behind a waterfall that is every bit as good as a nearly identical scene from The Lost World: Jurassic Park a few weeks later, and that was directed by Steven Spielberg himself.

Outside of the anaconda, Anaconda's pleasures are virtually all ironic, or at least campy: there's a good amount of spot-the-bad-filmmaking to be had including a moment where an unnecessary shot of a boat reversing course is fabricated by simply running the footage backwards, so that we see a waterfall going upwards. For, like, a full second. Later, there's a slow-motion shot of blood being splashed on Lopez that gives us a nice long look at how blood is not, in fact, being splashed on Lopez. And of course, Voight is a treasure trove of amazingly awful gems, from his threatening one-liners to his rhapsodising about baby snakes to his incomparable wink in the second-to-last shot where he appears in the whole movie. It's a thoroughly goofy movie, its saving grace; unlike many films in its genre, from this period or others, the meager attempts at sincerity and engagement with the plot are so flimsy that they don't bog the film down. Witness, for example, its ending, where we do meet the Shirishama, the mystically uplifting moment that the narrative was allegedly leading to, and the film's response is to find it so unambiguously boring that it races for the credits at top speed. It's not that it's knowing kitsch; Llosa's attempts to make the thriller scenes work demonstrates that. But it knows enough to stay out of the way of kitsch, and that's all it takes to make one of the most bubbly, top-to-bottom fun shitty movies of an entire generation.

Reviews in this series

Anaconda (Llosa, 1997)

Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid (Little, 2004)

Anaconda 3: Offspring (FauntLeRoy, 2008)

Anacondas: Trail of Blood (FauntLeRoy, 2009)

Lake Placid vs. Anaconda (Stone, 2015)

Categories: adventure, good bad movies, here be monsters, horror, thrillers