From the head of Seuss

A review requested by Looneygamemaster, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

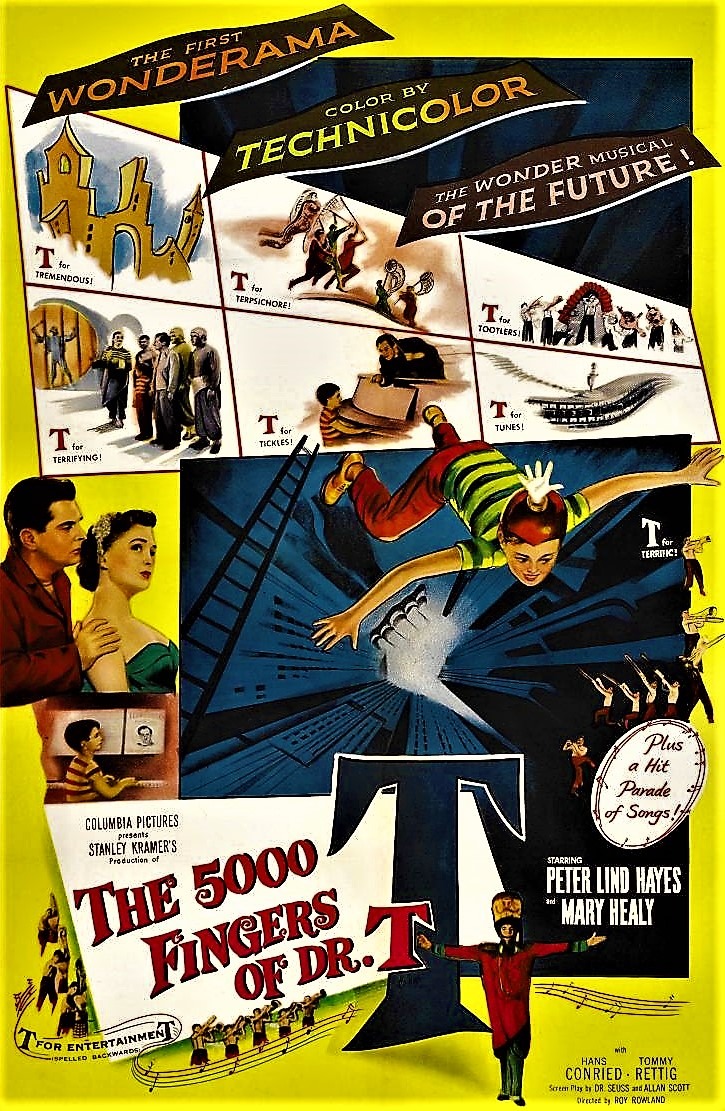

The version of The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T that we have is the hastily-reworked version of a more ambitious and potentially even more bizarre original cut for which the materials no longer exist, so let's not get excited. The point being, this is some demented and disorienting stuff even in the 89-minute version that was greeted with distaste from both critics and audiences during its catastrophic release in 1953, so we can really only imagine how much dizzying the original cut must have been. And, I think, we can and should take pity on the preview audiences whose rejection of that cut has made it impossible for any of the rest of us to ever see it. This is not a film for people in 1953. In fact, I think that The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T offers us a paradox: it could only really have succeeded decades later, when the '70s and '80s had normalized the idea of warped, fucked-up children's entertainment in the United States, and Dr. Seuss (the creative wellspring for the story and the design) had transitioned fully into "beloved figure of nostalgia" rather than a major figure in contemporary children's pop culture, in the midst of writing his best-known and most iconic works. But it also really could only have been made in the '50s, during the waning days of the Hollywood studio system and the golden age of the stagebound Technicolor musical. So perhaps it was always doomed to the exact fate it received: massive mainstream failure preceding its later recovery as a cult film. Which is a rough fate for an unabashed kids' film, though I presume that actual children make up some small portion that cult.

The film came about because of Theodor Seuss Geisel's great success at having collaborated with Columbia Pictures on its Jolly Frolics cartoon series, produced by United Productions of America (UPA); he'd written the script for 1950 Oscar-winning Gerald McBoing-Boing, one of the great American cartoons, and immediately recognised as such. It presumably made a great deal of sense to both Geisel and Columbia to find new avenues to work together, though as it turned out, Geisel didn't necessarily know much about movies (his first draft of the screenplay was reportedly 1200 pages long), and the project had the misfortune to become a point of contention in the war between Columbia studio head Harry Cohn and producer Stanley Kramer. The result was an unequivocal dead end: Geisel wrote nothing else for Columbia nor any other Hollywood studio until working on the script for the 1966 television special How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, and there would never again be a feature-length Dr. Seuss project until years after Geisel's death in 1991, when the live-action 2000 Grinch came out and proved that live-action was probably not the right way to go.

At least, not the right way to go in 2000. 47 years earlier was a different time, and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is, if not an unmixed success, and in some key ways maybe not technically "good", at least it's lively and peculiar enough to feel like a worthy experiment in trying to make Seuss-style visuals work in live-action. One never likes to give credit to Kramer, who wanted to direct this himself but was blocked by Cohn but remained a very hands-on producer (the job was given to Roy Rowland, a journeyman director of sturdy-enough talent who made very few films of note, certainly none moreso than this), but this is a very intelligent and intentional approach to the task of making this visual translation happen. Certainly, the film benefits from the decades-later comparison of How the Grinch Stole Christmas, which found Ron Howard and his design team embracing a suffocating, aesthetically deadened literalism in simply using Seuss's drawings as a blueprint: The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T was designed to be a movie first and foremost, rather than retrofitted from a picture book, and so its impossible, otherworldly sets have been conceived as places for actors to move about with angles that will allow cameras to reveal their details gradually and purposefully, not just barfing all over us.

One particularly smart choice made by the design team - production designer Rudolph Sternad, art director Cary Odell, set decorator William Kiernan (the film has no credited costume designer, only one of those weird and unhelpful "gowns by" credits you see a lot in the '50s. The gowns were by Jean Louis, for what it's worth) - was to recognise that part of the visual appeal of Dr. Seuss's illustrations is, counterintuitively, their minimalism. They are, for the most part, line drawings: limited shading, backgrounds (especially exteriors) are often just large white spaces, most of his books have restricted color palettes. The particular effects of his illustrations are more about the shapes themselves, the serpentine and unpredictable lines, the detachment from realistic physics. There's not much that a movie shot on actual sets with actual people can do to detach itself from realistic physics (which isn't to say that it can do nothing), but The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T goes all in on the squirmy lines. And, for that matter, the negative space: this is a downright cavernous film in a lot of places, with its defining set (an enormous castle hall with an endless piano keyboard writhing around every wall on two levels) as notable for how shockingly empty it is, how most of what we see is an ominous grey wall, looming hugely over the keyboards. This is the most dramatic example of the film's strategy of, I don't know what to call it, "maximalist understatement", maybe. But there are a great many scenes throughout where the feeling of open air above the actors' heads dominates, along with the sparseness of the decor, and the limited range of the color palette. And this extends to its effects shots, the places where it uses some superb matte paintings to get at that Seussian anti-gravity; one of the most delightful shots in the film, to me, is very little other than a bright red ladder against a royal blue background, hovering impossibly in mid-air, with the main character a little smudge in extreme wide shot. It's genuinely dreamy and surreal like very little else in mainstream filmmaking in 1950s America, drawing on the basic principles of Expressionist filmmaking from 20 and 30 years earlier: surprising lines, strong contrast, physical illogic - but never excess.

Excess, instead, comes in the form of the film's extremely joyful and downright cartoony costume design, which is part of why it frustrates me that there's no credited costume designer. Given that the ultimate origin of this film was Dr. Seuss's working relationship with UPA, it's desperately tempting to call this the live-action version of UPA's distinctive style: lots of sparse, flat, even undefined environments, with striking and weird "character animation". Which is an inappropriate way to describe flesh-and-blood actors, I concede, though in the case of Hans Conried's performance as the hambone villain, it's only barely inappropriate. But it's very much the same effect: most of the visual imagination accrues to the figures themselves, with the brightest colors, the most bizarre shapes, the most surreal and vaguely horrifying concepts. Sometimes it's cute, as in the little beanie with a rubbery hand worn by the put-upon child protagonist. Sometimes it's freaky and warped in a funny way, as in the dungeon full of musical instrument people. Sometimes it's just joyously goofy and silly, as in most of the things that Conried gets swaddled in, with their eye-searing pinks and purples and blues.

If all this makes it sound like the main appeal of The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is strictly related to its design, and the way it builds a giddy, goofy, surreal world: that's correct. The draw here is watching Seussian logic insisting itself upon actual humans. Which isn't to say that the story motivating all of that design is "bad". The final draft of the script, by Dr. Seuss & Allan Scott (a specialist in musicals nearing the end of his career, including most of the best-loved Astaire & Rogers pictures), tells a perfectly straightforward story that has been executed with admirably pure "child's logic": this little boy named Bartholomew Collins (Tommy Rettig) hates practicing piano under the bullying attention of Dr. Terwilliker (Conried), the author of a popular series of "teach your child to play piano" guides that I'm pretty sure we're meant to understand is a whole bunch of hogwash. But that's thinking like an adult, and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is not welcoming us to think like an adult. We just know that Terwilliker is a mean dick who makes Bart do something he hates, just because his middle-class widowed mother (Mary Healy) has obviously gotten it into her head that this is something nice middle-class children do. Apologies! Thinking like an adult again.

The bulk of the movie is a dream sequence, with Bart so wearied by playing that he drifts off into a nightmare in which Dr. Terwilliker is a mad scientist and slaver of children, who wishes to have 500 young boys play his greatest composition; in this nightmare, Mrs. Collins is his brainwashed second-in-command and the only ally Bart can find is the dream version of Mr. Zabladowski (Peter Lind Hayes), his mother's handyman in reality who is here presented as another one of Terwilliker's unwitting lackies, installing the sinks that are required if the mad doctor's castle/prison is to pass a health and safety inspection before he can stage his great boys' concert. Along the way, many weird and zany things are encountered, from that dungeon of musical instrument people to a pair of brothers conjoined at the beard (John & Robert Heasley). Many songs are performed, the best of which are vaguely menacing ditties with lots of squirrely Seussian wordplay (the best, by far, is a song in which Terwilliker sings about the outfits he wants to be dressed in), the worst of which are thin, syrupy ballads that I suspect felt less of an imposition when the film had more songs (part of the recuts involved reducing the song list by almost half), and I presume more silly songs.

It's cute enough, but not especially "new" - even by 1953 standards, I can't imagine not immediately clocking this as yet another Wizard of Oz riff - and I don't really imagine that the film would have any sort of reputation just based on the story. It's a perfectly well-executed version of the story, mostly because of how sincerely it commits to being the best possible movie about a child's understanding of the world it can be. Rettig is a good child actor by the standards of his era, which to be fair was among the worst times for child actors in the history of Hollywood. But that's not meant to be backhanded praise. He navigates the clunky exposition of the opening scene, full of direct address, with a decent amount of wry humor and rubbery facial expressions, and through the bulk of the film that requires him to do nothing more than gawk at the bizarre designs, he's doing so without hamming things up, reacting with the wariness of someone who constantly feels a low purr of danger, rather than being a little kid responding to the cue "be scared". And that matters a lot, in fact, because having Bart be relatively plain and normal is necessary if Conried's unhinged, ranting, bug-eyed performance is going to seem appropriately garish and destabilising.

Plus, Seuss & Scott's script very earnestly replicates the limited perspective and odd connections made by an observant but not particularly clever little boy who is trying his best to parse what seems like very strange behavior from the adults around him. This, more than anything, is what makes The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T feel emphatically like a children's movie, more than a "family movie", and certainly more than a cult movie; but the children of the world deserve movies made with care and attention by thoughtful filmmakers. It is, I would go so far to say, one of the best children's movies of its generation, never pandering, always imaginative, and always delightful to look at. There's never a sense that the creators are "lowering themselves" to work on such blatantly silly material, and we need more children's cinema for which that's true - hell, we need more adults' cinema for which that's true.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

The version of The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T that we have is the hastily-reworked version of a more ambitious and potentially even more bizarre original cut for which the materials no longer exist, so let's not get excited. The point being, this is some demented and disorienting stuff even in the 89-minute version that was greeted with distaste from both critics and audiences during its catastrophic release in 1953, so we can really only imagine how much dizzying the original cut must have been. And, I think, we can and should take pity on the preview audiences whose rejection of that cut has made it impossible for any of the rest of us to ever see it. This is not a film for people in 1953. In fact, I think that The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T offers us a paradox: it could only really have succeeded decades later, when the '70s and '80s had normalized the idea of warped, fucked-up children's entertainment in the United States, and Dr. Seuss (the creative wellspring for the story and the design) had transitioned fully into "beloved figure of nostalgia" rather than a major figure in contemporary children's pop culture, in the midst of writing his best-known and most iconic works. But it also really could only have been made in the '50s, during the waning days of the Hollywood studio system and the golden age of the stagebound Technicolor musical. So perhaps it was always doomed to the exact fate it received: massive mainstream failure preceding its later recovery as a cult film. Which is a rough fate for an unabashed kids' film, though I presume that actual children make up some small portion that cult.

The film came about because of Theodor Seuss Geisel's great success at having collaborated with Columbia Pictures on its Jolly Frolics cartoon series, produced by United Productions of America (UPA); he'd written the script for 1950 Oscar-winning Gerald McBoing-Boing, one of the great American cartoons, and immediately recognised as such. It presumably made a great deal of sense to both Geisel and Columbia to find new avenues to work together, though as it turned out, Geisel didn't necessarily know much about movies (his first draft of the screenplay was reportedly 1200 pages long), and the project had the misfortune to become a point of contention in the war between Columbia studio head Harry Cohn and producer Stanley Kramer. The result was an unequivocal dead end: Geisel wrote nothing else for Columbia nor any other Hollywood studio until working on the script for the 1966 television special How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, and there would never again be a feature-length Dr. Seuss project until years after Geisel's death in 1991, when the live-action 2000 Grinch came out and proved that live-action was probably not the right way to go.

At least, not the right way to go in 2000. 47 years earlier was a different time, and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is, if not an unmixed success, and in some key ways maybe not technically "good", at least it's lively and peculiar enough to feel like a worthy experiment in trying to make Seuss-style visuals work in live-action. One never likes to give credit to Kramer, who wanted to direct this himself but was blocked by Cohn but remained a very hands-on producer (the job was given to Roy Rowland, a journeyman director of sturdy-enough talent who made very few films of note, certainly none moreso than this), but this is a very intelligent and intentional approach to the task of making this visual translation happen. Certainly, the film benefits from the decades-later comparison of How the Grinch Stole Christmas, which found Ron Howard and his design team embracing a suffocating, aesthetically deadened literalism in simply using Seuss's drawings as a blueprint: The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T was designed to be a movie first and foremost, rather than retrofitted from a picture book, and so its impossible, otherworldly sets have been conceived as places for actors to move about with angles that will allow cameras to reveal their details gradually and purposefully, not just barfing all over us.

One particularly smart choice made by the design team - production designer Rudolph Sternad, art director Cary Odell, set decorator William Kiernan (the film has no credited costume designer, only one of those weird and unhelpful "gowns by" credits you see a lot in the '50s. The gowns were by Jean Louis, for what it's worth) - was to recognise that part of the visual appeal of Dr. Seuss's illustrations is, counterintuitively, their minimalism. They are, for the most part, line drawings: limited shading, backgrounds (especially exteriors) are often just large white spaces, most of his books have restricted color palettes. The particular effects of his illustrations are more about the shapes themselves, the serpentine and unpredictable lines, the detachment from realistic physics. There's not much that a movie shot on actual sets with actual people can do to detach itself from realistic physics (which isn't to say that it can do nothing), but The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T goes all in on the squirmy lines. And, for that matter, the negative space: this is a downright cavernous film in a lot of places, with its defining set (an enormous castle hall with an endless piano keyboard writhing around every wall on two levels) as notable for how shockingly empty it is, how most of what we see is an ominous grey wall, looming hugely over the keyboards. This is the most dramatic example of the film's strategy of, I don't know what to call it, "maximalist understatement", maybe. But there are a great many scenes throughout where the feeling of open air above the actors' heads dominates, along with the sparseness of the decor, and the limited range of the color palette. And this extends to its effects shots, the places where it uses some superb matte paintings to get at that Seussian anti-gravity; one of the most delightful shots in the film, to me, is very little other than a bright red ladder against a royal blue background, hovering impossibly in mid-air, with the main character a little smudge in extreme wide shot. It's genuinely dreamy and surreal like very little else in mainstream filmmaking in 1950s America, drawing on the basic principles of Expressionist filmmaking from 20 and 30 years earlier: surprising lines, strong contrast, physical illogic - but never excess.

Excess, instead, comes in the form of the film's extremely joyful and downright cartoony costume design, which is part of why it frustrates me that there's no credited costume designer. Given that the ultimate origin of this film was Dr. Seuss's working relationship with UPA, it's desperately tempting to call this the live-action version of UPA's distinctive style: lots of sparse, flat, even undefined environments, with striking and weird "character animation". Which is an inappropriate way to describe flesh-and-blood actors, I concede, though in the case of Hans Conried's performance as the hambone villain, it's only barely inappropriate. But it's very much the same effect: most of the visual imagination accrues to the figures themselves, with the brightest colors, the most bizarre shapes, the most surreal and vaguely horrifying concepts. Sometimes it's cute, as in the little beanie with a rubbery hand worn by the put-upon child protagonist. Sometimes it's freaky and warped in a funny way, as in the dungeon full of musical instrument people. Sometimes it's just joyously goofy and silly, as in most of the things that Conried gets swaddled in, with their eye-searing pinks and purples and blues.

If all this makes it sound like the main appeal of The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is strictly related to its design, and the way it builds a giddy, goofy, surreal world: that's correct. The draw here is watching Seussian logic insisting itself upon actual humans. Which isn't to say that the story motivating all of that design is "bad". The final draft of the script, by Dr. Seuss & Allan Scott (a specialist in musicals nearing the end of his career, including most of the best-loved Astaire & Rogers pictures), tells a perfectly straightforward story that has been executed with admirably pure "child's logic": this little boy named Bartholomew Collins (Tommy Rettig) hates practicing piano under the bullying attention of Dr. Terwilliker (Conried), the author of a popular series of "teach your child to play piano" guides that I'm pretty sure we're meant to understand is a whole bunch of hogwash. But that's thinking like an adult, and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is not welcoming us to think like an adult. We just know that Terwilliker is a mean dick who makes Bart do something he hates, just because his middle-class widowed mother (Mary Healy) has obviously gotten it into her head that this is something nice middle-class children do. Apologies! Thinking like an adult again.

The bulk of the movie is a dream sequence, with Bart so wearied by playing that he drifts off into a nightmare in which Dr. Terwilliker is a mad scientist and slaver of children, who wishes to have 500 young boys play his greatest composition; in this nightmare, Mrs. Collins is his brainwashed second-in-command and the only ally Bart can find is the dream version of Mr. Zabladowski (Peter Lind Hayes), his mother's handyman in reality who is here presented as another one of Terwilliker's unwitting lackies, installing the sinks that are required if the mad doctor's castle/prison is to pass a health and safety inspection before he can stage his great boys' concert. Along the way, many weird and zany things are encountered, from that dungeon of musical instrument people to a pair of brothers conjoined at the beard (John & Robert Heasley). Many songs are performed, the best of which are vaguely menacing ditties with lots of squirrely Seussian wordplay (the best, by far, is a song in which Terwilliker sings about the outfits he wants to be dressed in), the worst of which are thin, syrupy ballads that I suspect felt less of an imposition when the film had more songs (part of the recuts involved reducing the song list by almost half), and I presume more silly songs.

It's cute enough, but not especially "new" - even by 1953 standards, I can't imagine not immediately clocking this as yet another Wizard of Oz riff - and I don't really imagine that the film would have any sort of reputation just based on the story. It's a perfectly well-executed version of the story, mostly because of how sincerely it commits to being the best possible movie about a child's understanding of the world it can be. Rettig is a good child actor by the standards of his era, which to be fair was among the worst times for child actors in the history of Hollywood. But that's not meant to be backhanded praise. He navigates the clunky exposition of the opening scene, full of direct address, with a decent amount of wry humor and rubbery facial expressions, and through the bulk of the film that requires him to do nothing more than gawk at the bizarre designs, he's doing so without hamming things up, reacting with the wariness of someone who constantly feels a low purr of danger, rather than being a little kid responding to the cue "be scared". And that matters a lot, in fact, because having Bart be relatively plain and normal is necessary if Conried's unhinged, ranting, bug-eyed performance is going to seem appropriately garish and destabilising.

Plus, Seuss & Scott's script very earnestly replicates the limited perspective and odd connections made by an observant but not particularly clever little boy who is trying his best to parse what seems like very strange behavior from the adults around him. This, more than anything, is what makes The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T feel emphatically like a children's movie, more than a "family movie", and certainly more than a cult movie; but the children of the world deserve movies made with care and attention by thoughtful filmmakers. It is, I would go so far to say, one of the best children's movies of its generation, never pandering, always imaginative, and always delightful to look at. There's never a sense that the creators are "lowering themselves" to work on such blatantly silly material, and we need more children's cinema for which that's true - hell, we need more adults' cinema for which that's true.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.