Gentleman of the West

A review requested by Stephen, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

I think there is a very strong argument to be made that Leo McCarey was the greatest conservative filmmaker in the history of Hollywood - and the argument isn't, just to be clear, whether he was a conservative. His major passion project, 1945's The Bells of St. Mary's, was a pro-Catholic propaganda film, and he was only able to secure financing for it by making a different pro-Catholic propaganda film, 1944's Going My Way. He was a friendly witness for HUAC. There can be no reasonable doubt about his views. And I'm also not remotely arguing that he was the greatest filmmaker who held conservative personal beliefs; setting aside the thorny question of what exactly John Ford's politics were, we still have Howard Hawks sitting right there. What I'm suggesting is that his greatest films - outside of the special case of Duck Soup, a Marx Brothers film more than a McCarey film - generally share an unmissable conservative bent, and this cannot be disentangled from their greatness. The Awful Truth: the defining movie in the "comedy of remarriage" cycle, in which divorce is viewed with a kind of genial disgust, as we wait for the couple to realise that they were damn fools for trying to separate. Make Way for Tomorrow: an unfathomably devastating tragedy about the horrors of children who don't love their parents enough. Even the smoldering paean to extramarital romance, Love Affair (and its McCarey-directed remake, An Affair to Remember) ends up feeling more about the communion and spiritual commitment of two souls, rather than the electric connection of two bodies.

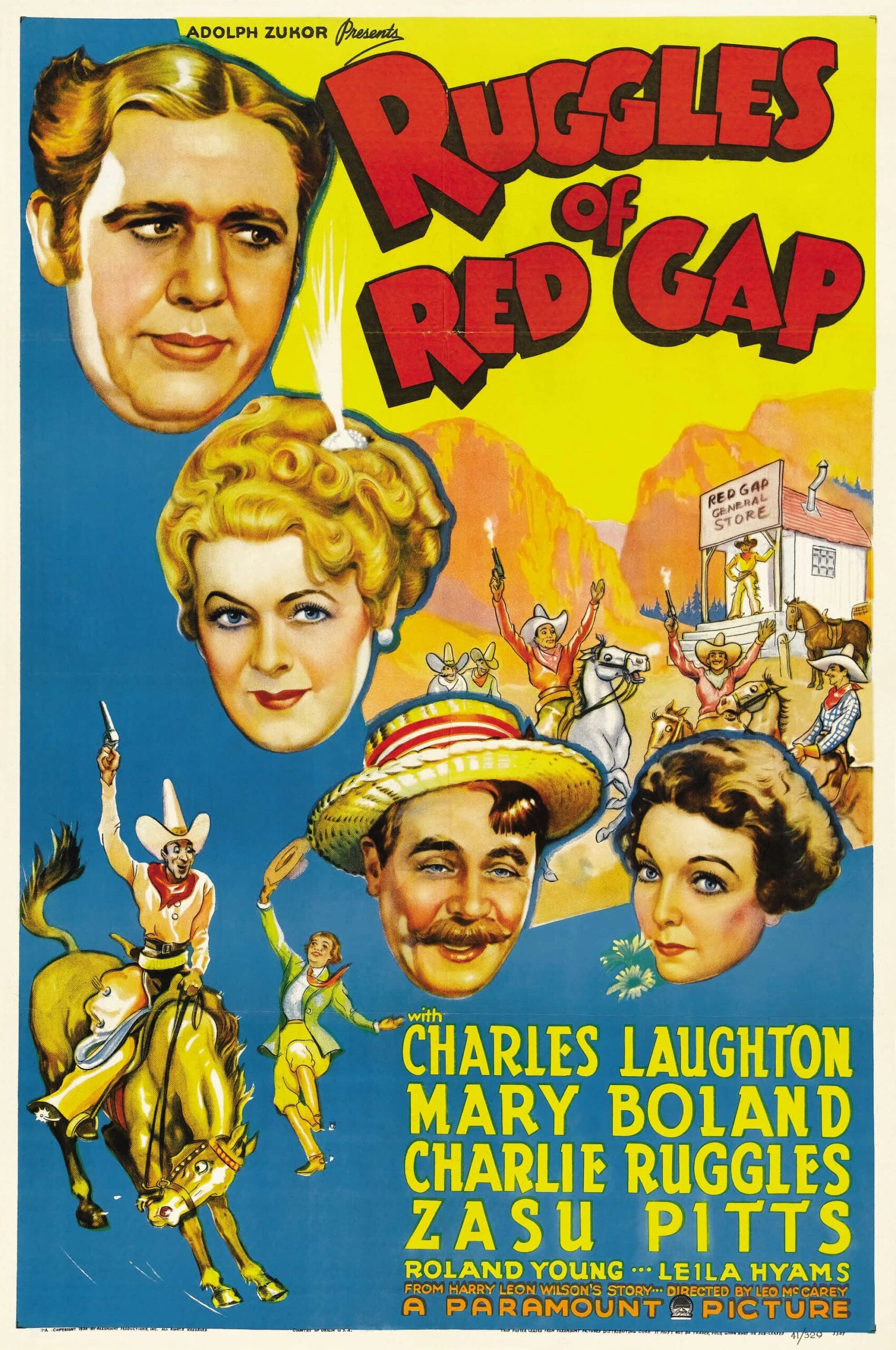

This is, of course, all leading me to Ruggles of Red Gap, the 1935 film with which McCarey began to transition out of the first major phase of his feature directorial career, where he was mostly working to facilitate movies around major comic stars: Eddie Cantor, the Marxes, W.C. Fields, Mae West. He wasn't quite done with that mode - his very next film was The Milky Way, Harold Lloyd's most successful sound film - but despite the presence of its own major star in Charles Laughton (who was not, of course, primarily or even significantly a comic actor), Ruggles of Red Gap feels much more in keeping with the more delicately-built, character-driven pieces that would start with his next film after The Milky Way, that very same ultra-depressing Make Way for Tomorrow. It's absolutely terrific, playing an exceptionally high concept for loose, improvisatory character beats rather than big laughs; and the reason I started with that big long musing on McCarey's politics is that I think this is also, outside of the Catholic dyad, perhaps the film where his conservative impulses are laid bare most clearly, and to finest effect. Made right smack-dab in the middle of the Great Depression, Ruggles of Red Gap is a celebration of the mythology of the United States of America as the great land of egalitarianism and democracy, where every man belongs to himself and can carve out his own place in the world just as long as he has the can-do gumption to do it. Its signature moment - and a hell of a scene it is - finds a bar full of Western ruffians stopping cold in patriotic sentimentality at a recitation of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address - delivered by a foreigner, no less. It's a film that believes in the daydream version of America as a land of apple pie and opportunity and all those homey things with as much fervor as any movie has every believed in those things.

What sets this apart from the mildewy, gummy trash that "conservative cinema" has become in the last decades is that McCarey was an absolute genius, particularly when it came to working with actors and giving them room to play around with beats, building characters from the moments between moments. Ruggles of Red Gap is a particularly impressive achievement on this front, given that it was packed with actors who, in the wrong hands, could be mercilessly prone to hammy mugging. Laughton was one of these, of course: I love him a lot, but it would be a filthy lie to say he was interested in restraint, and even when he was doing careful, disciplined character work, it tended to be pitched awfully loud. In the supporting case, we find plenty of other actors prone to eschewing subtlety: Charlie Ruggles as a hootin' and hollerin' embodiment of frontier ruggedness, Mary Boland as a snippy, snappish uncouth woman shouting indignantly at anything remotely smacking of tomfoolery, Roland Young as an addled English blueblood whose upper lip would snap right off if it was any stiffer, and ZaSu Pitts as... anything at all, really. Not to say that Ruggles of Red Gap finds these people all working in a register of subdued naturalism all of the time, but it's certainly not an endless broadside of caricatured comic beats.

Indeed, Ruggles of Red Gap isn't really terribly "funny" for something made by a comedy specialist and with such an avowedly farcical premise: Ruggles (Laughton) the valet of the watery Earl of Burnstead (Young) is lost in a poker game to Egbert Floud (Ruggles), a nouveau riche oilman from Washington state, which at this point in time - the film is set in 1908 - hadn't been out of its "rough and tumble frontier wilderness" phase for all that long. Long enough, however, for the creeping influence of civilisation to show up, and Egbert's wife Effie (Boland) has decided that she wants to be the finest family in the town of Red Gap - and what better way to demonstrate how very sophisticated the Flouds are than to come back from a European vacation with an English valet in tow? And so it is that Ruggles finds himself in Red Gap, a place where his extremely traditionalist, class-fixated worldview finds absolutely no purchase, even by the standards of what the film insists is the resolutely class-blind U.S. of A. And once the culture shock wears off, Ruggles finds that he likes this very much, particularly once he starts flirting with the widow Judson (Pitts), a cook in the employ of local barkeep Nell Kenner (Leila Hyams).

The promise of Charles Laughton playing a haughty, stuck-up Brit being constantly amazed by the uncouth ways of Americans in the coarsest part of America doesn't last for very long; Ruggles of Red Gap is, somewhat surprisingly and definitely to its benefit, not really a culture-clash comedy. There's a bit of that early on, when Ruggles is first attached to the Flouds in Paris, during the rather unexpectedly stretched-out first act (the film just barely passes by 90 minutes; about one-third of that time is spent in France). This really the only part of the film where Laughton plays Ruggles "big", and of course bigness in this case must be amended by noting that sort the whole "thing" is that Ruggles is so serenely restrained and collected that he doesn't permit himself to have actual reactions. What I rather mean is that it's mostly during this first act that Laughton allows us to see the profound terror that Ruggles feels at the thought of being manservant to some idiot Yanks, almost exclusively through widening his eyes and flicking his gaze back and forth with more frantic energy than he'll display later in the film. Laughton strikes a singular mixture of almost complete stasis - he's generally holding his entire body and head rock steady in these beats - with excessive, damn near campy over-emphasis in how much he's selling these tiny, tiny gestures. It's kind of weird, but I think it works superbly: the sense of all-encompassing panic that Ruggles exudes in the early going, while retaining his ironclad commitment to surfaces and propriety, is both some of the movie's funniest material and a terrific introduction to the character whose gentle, gradual softening will be the film's primary focus.

Which gets me back to the thing where despite its enormous charms and its almost exclusively goofy cast, Ruggles of Red Gap never seems to be going for uproarious laughter. It's ultimately a character story: about how one uptight Brit, welcomed to the casual and laid-back world of Red Gap, finds himself able to just enjoy himself. This is occasionally played for the broadest of comedy, as when Ruggles and Egbert have a drunken carouse in Paris, but just as often, it's mostly just nice: watching pleasant enough character - and I don't think Laughton ever played a more genial, purely likable character, and even in the same year as his monstrous Captain Bligh in Mutiny on the Bounty, no less - unwind and learn how to at chummy and to speak up for himself.

This is an extraordinary swerve for McCarey to make, and it would pay off wonderfully, here and in his subsequent career. He is, I think, one of the great (and greatly underappreciated) directors of actors from his generation of Hollywood, in large part because of how much he room he allowed his casts to improvise and explore and find the contours of their characters, rather than letting them lean into the types offered by the script. This results in things like Irene Dunne's career-best performance as rather shockingly low-key melodrama heroine in Love Affair or Barry Fitzgerald's career-best performance as a muted and tired Irish priest in Going My Way, with none of the actor's characteristic cartoon affectations. "Naturalism" would be stretching it, but it's all very loose and casual, organic character beats trumping mechanically precise ones; we're often watching characters in-between their dramatic beats, in a way, focused more on reactions than actions. This approach is particularly remarkable in Ruggles of Red Gap, which gets this cast of all casts to commit to underplaying: Charlie Ruggles is probably the only actor who goes broad more often than not (in large part because he's the only actor whose part is substantially based in dialect humor, given Egbert's big cornpone accent and unrefined speech patterns).

To further encourage this overall feeling of laid-back people-watching, McCarey relies on some extremely long takes; a common approach in comedies of this era, to be sure, but there are a few key moments where the sense of living in a moment and just seeing where it goes completely dominates the plotting. This is the heart of that wonderful Gettysburg Address scene, which begins with Egbert making some semi-pretentious remark about "what Lincoln said", at which point it becomes clear that neither he nor any other patron of Nell's place in fact knows what Lincoln said. To get there, McCarey and cinematographer Alfred Gilks send the camera on a meandering spiral around the inside of the bar, following the flow of conversation as it gets handed off from one barfly to the next, each of them stymied in trying to recall the text. It's such a lovely, incredibly present moment, connecting all of the characters in a cozy little web, making the room and its inhabitants feel all tangled up in each other's lives, and making the camera itself a desperately curious member of that community, looking around at each one of these people. The punchline, of course, is that Ruggles knows it all by heart, and here the film reverses itself, revisiting each of those men with cuts, rather than camera movement, giving them a chance to be alone with their reaction to Laughton's careful and soothing delivery of the speech.

It's the showiest moment in a film that rarely wants to show off, which is undoubtedly part of why it lands so well. At the same time, the filmmaking in Ruggles of Red Gap always feels precise, carefully shaping the characters and world even as the characters themselves feel like they're constantly surprising themselves and us. I don't think it's his best film - Duck Soup and Make Way for Tomorrow are obviously better, and it's hard to come up with a good argument against either of the Irene Dunne pictures - but I think it is maybe the one that best shows off this particular strength of his, this kind of hyper-precise looseness. And even ignoring auteurist concerns, the warmth of the character work and the deep earnestness of its belief that people deserve every opportunity and encouragement to become their best selves would be enough to make this one of the great hidden gems of 1930s American cinema.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

I think there is a very strong argument to be made that Leo McCarey was the greatest conservative filmmaker in the history of Hollywood - and the argument isn't, just to be clear, whether he was a conservative. His major passion project, 1945's The Bells of St. Mary's, was a pro-Catholic propaganda film, and he was only able to secure financing for it by making a different pro-Catholic propaganda film, 1944's Going My Way. He was a friendly witness for HUAC. There can be no reasonable doubt about his views. And I'm also not remotely arguing that he was the greatest filmmaker who held conservative personal beliefs; setting aside the thorny question of what exactly John Ford's politics were, we still have Howard Hawks sitting right there. What I'm suggesting is that his greatest films - outside of the special case of Duck Soup, a Marx Brothers film more than a McCarey film - generally share an unmissable conservative bent, and this cannot be disentangled from their greatness. The Awful Truth: the defining movie in the "comedy of remarriage" cycle, in which divorce is viewed with a kind of genial disgust, as we wait for the couple to realise that they were damn fools for trying to separate. Make Way for Tomorrow: an unfathomably devastating tragedy about the horrors of children who don't love their parents enough. Even the smoldering paean to extramarital romance, Love Affair (and its McCarey-directed remake, An Affair to Remember) ends up feeling more about the communion and spiritual commitment of two souls, rather than the electric connection of two bodies.

This is, of course, all leading me to Ruggles of Red Gap, the 1935 film with which McCarey began to transition out of the first major phase of his feature directorial career, where he was mostly working to facilitate movies around major comic stars: Eddie Cantor, the Marxes, W.C. Fields, Mae West. He wasn't quite done with that mode - his very next film was The Milky Way, Harold Lloyd's most successful sound film - but despite the presence of its own major star in Charles Laughton (who was not, of course, primarily or even significantly a comic actor), Ruggles of Red Gap feels much more in keeping with the more delicately-built, character-driven pieces that would start with his next film after The Milky Way, that very same ultra-depressing Make Way for Tomorrow. It's absolutely terrific, playing an exceptionally high concept for loose, improvisatory character beats rather than big laughs; and the reason I started with that big long musing on McCarey's politics is that I think this is also, outside of the Catholic dyad, perhaps the film where his conservative impulses are laid bare most clearly, and to finest effect. Made right smack-dab in the middle of the Great Depression, Ruggles of Red Gap is a celebration of the mythology of the United States of America as the great land of egalitarianism and democracy, where every man belongs to himself and can carve out his own place in the world just as long as he has the can-do gumption to do it. Its signature moment - and a hell of a scene it is - finds a bar full of Western ruffians stopping cold in patriotic sentimentality at a recitation of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address - delivered by a foreigner, no less. It's a film that believes in the daydream version of America as a land of apple pie and opportunity and all those homey things with as much fervor as any movie has every believed in those things.

What sets this apart from the mildewy, gummy trash that "conservative cinema" has become in the last decades is that McCarey was an absolute genius, particularly when it came to working with actors and giving them room to play around with beats, building characters from the moments between moments. Ruggles of Red Gap is a particularly impressive achievement on this front, given that it was packed with actors who, in the wrong hands, could be mercilessly prone to hammy mugging. Laughton was one of these, of course: I love him a lot, but it would be a filthy lie to say he was interested in restraint, and even when he was doing careful, disciplined character work, it tended to be pitched awfully loud. In the supporting case, we find plenty of other actors prone to eschewing subtlety: Charlie Ruggles as a hootin' and hollerin' embodiment of frontier ruggedness, Mary Boland as a snippy, snappish uncouth woman shouting indignantly at anything remotely smacking of tomfoolery, Roland Young as an addled English blueblood whose upper lip would snap right off if it was any stiffer, and ZaSu Pitts as... anything at all, really. Not to say that Ruggles of Red Gap finds these people all working in a register of subdued naturalism all of the time, but it's certainly not an endless broadside of caricatured comic beats.

Indeed, Ruggles of Red Gap isn't really terribly "funny" for something made by a comedy specialist and with such an avowedly farcical premise: Ruggles (Laughton) the valet of the watery Earl of Burnstead (Young) is lost in a poker game to Egbert Floud (Ruggles), a nouveau riche oilman from Washington state, which at this point in time - the film is set in 1908 - hadn't been out of its "rough and tumble frontier wilderness" phase for all that long. Long enough, however, for the creeping influence of civilisation to show up, and Egbert's wife Effie (Boland) has decided that she wants to be the finest family in the town of Red Gap - and what better way to demonstrate how very sophisticated the Flouds are than to come back from a European vacation with an English valet in tow? And so it is that Ruggles finds himself in Red Gap, a place where his extremely traditionalist, class-fixated worldview finds absolutely no purchase, even by the standards of what the film insists is the resolutely class-blind U.S. of A. And once the culture shock wears off, Ruggles finds that he likes this very much, particularly once he starts flirting with the widow Judson (Pitts), a cook in the employ of local barkeep Nell Kenner (Leila Hyams).

The promise of Charles Laughton playing a haughty, stuck-up Brit being constantly amazed by the uncouth ways of Americans in the coarsest part of America doesn't last for very long; Ruggles of Red Gap is, somewhat surprisingly and definitely to its benefit, not really a culture-clash comedy. There's a bit of that early on, when Ruggles is first attached to the Flouds in Paris, during the rather unexpectedly stretched-out first act (the film just barely passes by 90 minutes; about one-third of that time is spent in France). This really the only part of the film where Laughton plays Ruggles "big", and of course bigness in this case must be amended by noting that sort the whole "thing" is that Ruggles is so serenely restrained and collected that he doesn't permit himself to have actual reactions. What I rather mean is that it's mostly during this first act that Laughton allows us to see the profound terror that Ruggles feels at the thought of being manservant to some idiot Yanks, almost exclusively through widening his eyes and flicking his gaze back and forth with more frantic energy than he'll display later in the film. Laughton strikes a singular mixture of almost complete stasis - he's generally holding his entire body and head rock steady in these beats - with excessive, damn near campy over-emphasis in how much he's selling these tiny, tiny gestures. It's kind of weird, but I think it works superbly: the sense of all-encompassing panic that Ruggles exudes in the early going, while retaining his ironclad commitment to surfaces and propriety, is both some of the movie's funniest material and a terrific introduction to the character whose gentle, gradual softening will be the film's primary focus.

Which gets me back to the thing where despite its enormous charms and its almost exclusively goofy cast, Ruggles of Red Gap never seems to be going for uproarious laughter. It's ultimately a character story: about how one uptight Brit, welcomed to the casual and laid-back world of Red Gap, finds himself able to just enjoy himself. This is occasionally played for the broadest of comedy, as when Ruggles and Egbert have a drunken carouse in Paris, but just as often, it's mostly just nice: watching pleasant enough character - and I don't think Laughton ever played a more genial, purely likable character, and even in the same year as his monstrous Captain Bligh in Mutiny on the Bounty, no less - unwind and learn how to at chummy and to speak up for himself.

This is an extraordinary swerve for McCarey to make, and it would pay off wonderfully, here and in his subsequent career. He is, I think, one of the great (and greatly underappreciated) directors of actors from his generation of Hollywood, in large part because of how much he room he allowed his casts to improvise and explore and find the contours of their characters, rather than letting them lean into the types offered by the script. This results in things like Irene Dunne's career-best performance as rather shockingly low-key melodrama heroine in Love Affair or Barry Fitzgerald's career-best performance as a muted and tired Irish priest in Going My Way, with none of the actor's characteristic cartoon affectations. "Naturalism" would be stretching it, but it's all very loose and casual, organic character beats trumping mechanically precise ones; we're often watching characters in-between their dramatic beats, in a way, focused more on reactions than actions. This approach is particularly remarkable in Ruggles of Red Gap, which gets this cast of all casts to commit to underplaying: Charlie Ruggles is probably the only actor who goes broad more often than not (in large part because he's the only actor whose part is substantially based in dialect humor, given Egbert's big cornpone accent and unrefined speech patterns).

To further encourage this overall feeling of laid-back people-watching, McCarey relies on some extremely long takes; a common approach in comedies of this era, to be sure, but there are a few key moments where the sense of living in a moment and just seeing where it goes completely dominates the plotting. This is the heart of that wonderful Gettysburg Address scene, which begins with Egbert making some semi-pretentious remark about "what Lincoln said", at which point it becomes clear that neither he nor any other patron of Nell's place in fact knows what Lincoln said. To get there, McCarey and cinematographer Alfred Gilks send the camera on a meandering spiral around the inside of the bar, following the flow of conversation as it gets handed off from one barfly to the next, each of them stymied in trying to recall the text. It's such a lovely, incredibly present moment, connecting all of the characters in a cozy little web, making the room and its inhabitants feel all tangled up in each other's lives, and making the camera itself a desperately curious member of that community, looking around at each one of these people. The punchline, of course, is that Ruggles knows it all by heart, and here the film reverses itself, revisiting each of those men with cuts, rather than camera movement, giving them a chance to be alone with their reaction to Laughton's careful and soothing delivery of the speech.

It's the showiest moment in a film that rarely wants to show off, which is undoubtedly part of why it lands so well. At the same time, the filmmaking in Ruggles of Red Gap always feels precise, carefully shaping the characters and world even as the characters themselves feel like they're constantly surprising themselves and us. I don't think it's his best film - Duck Soup and Make Way for Tomorrow are obviously better, and it's hard to come up with a good argument against either of the Irene Dunne pictures - but I think it is maybe the one that best shows off this particular strength of his, this kind of hyper-precise looseness. And even ignoring auteurist concerns, the warmth of the character work and the deep earnestness of its belief that people deserve every opportunity and encouragement to become their best selves would be enough to make this one of the great hidden gems of 1930s American cinema.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.