Catholic tastes

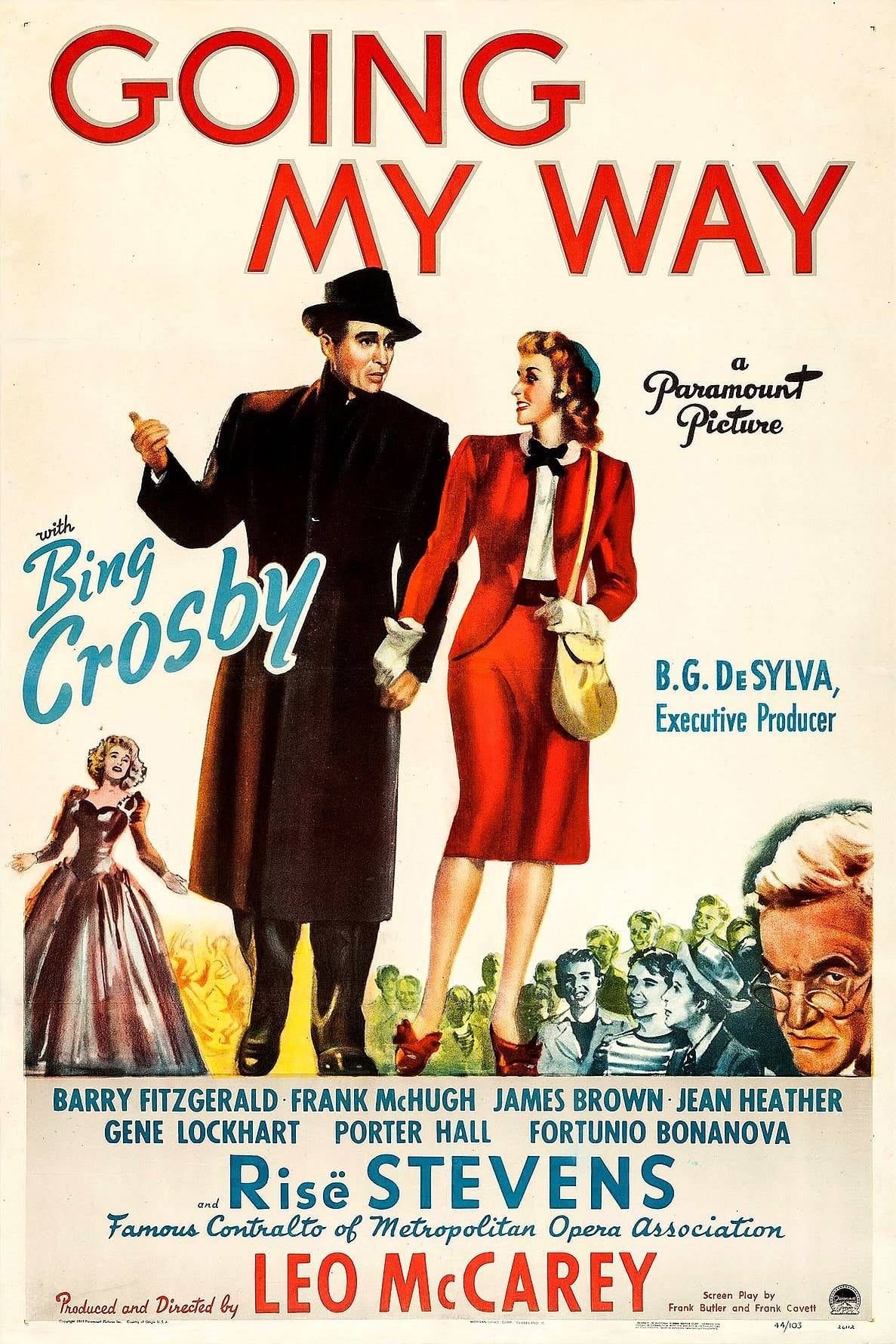

Before going into anything other details about 1944's Going My Way, it's probably appropriate to note that it was an enormous hit. It was the third highest-grossing film released during World War II in the United States, behind This Is the Army and For Whom the Bell Tolls (both released in 1943), making such an enormous quantity of money that it single-handedly turned Bing Crosby into the biggest movie star of the 1940s. And then went to win seven Oscars (one shy of the record at that time) out of 10 nominations, including Best Picture. It struck something in the Zeigest, no two ways about it, and I cannot honestly tell you what that was. "It's uplifting!" - well, sure, but a lot of other movies are too, more in the '40 than in modern times, for that matter. And it's not, like that uplifting. There's actually an unexpected, sort of appealing looseness to the film that means, among many other things, that it never really acts like a big triumphant crowdpleaser. It just sort of shuffles around, occasionally warming our hearts but also just as occasionally remaining slightly cool and downbeat. Besides which, the film is, like, extraordinarily Catholic, which seems like it ought to have curtailed its financial hopes at least somewhat.

Anyway, I have no answers to the question of why, exactly, Going My Way should be one of the defining films of 1940s popular cinema, but it does seem important to acknowledge that it most certainly was. This puts a certain pressure on it that it's not really built to endure - this is one of the quintessential "that won Best Picture?" movies, and not only because it beat Double Indemnity, one of the most enduring films of the decade. Lots of movies beat better movies for Oscars, and plenty of downright shitty movies have been dubiously named Best Picture, but even something as abject as 1937's The Life of Emile Zola still makes sense, cynically: it rather strenuously declares its importance and weight and demands respect. One of the most salient characteristics of Going My Way is that it doesn't do that at all; it's very easygoing and light and while it probably doesn't mind if we walk out feeling like we've learned something, it's not really going out of its way to teach us anything.

Even the existence of the film is something of a "sure, why not" story. Director and producer Leo McCarey, a devout Irish-American Catholic, had a story idea he badly wanted to make into film, about a progressive priest and a strait-laced nun who butt heads over how best to help secure the future of a run-down parochial school in New York. That idea was turned into a screenplay by Dudley Nichols, under the name The Bells of St. Mary's, and McCarey tried his god-damnedest gosh-darnedest to get it made, but none of the studios would bite. For reason that I do not quite understand, however, Paramount agreed to make a different film about the same progressive priest, and so McCarey came up with an almost identical story replacing the nun with another priest, and having writers Frank Butler and Frank Cavett work it into a screenplay. After the success of Going My Way, McCarey got to make The Bells of St. Mary's, which was an even bigger hit, as well as being the better film, and there's some bits of mildly amusing trivia that centers on it that I'll go into at such time as I get around to reviewing it. The point being, Going My Way was relatively an afterthought, the movie McCarey made because he couldn't make the "real" one.

That's a shitty way of putting it, and it's not like Going My Way is some slopped-together hackwork. Indeed, at its best, the film ably showcases McCarey's excellent gift for stepping back and watching human behavior, ungainly and interesting as it can be (among other things, it is shockingly forthright about the existence of sex and prostitution). The film focuses on Father Chuck O'Malley (Crosby), who we know is a relaxed, modern sort because he goes by "Chuck"; he's been called from St. Louis to put some order into St. Dominic's in New York, a place that has been lovingly but ineptly run for 45 years by Father Fitzgibbon (Barry Fitzgerald). To save Fitzgibbon's pride, and avoid any squabbling, the bishop and O'Malley have agreed to let the old man suppose that O'Malley is just his assistant, while the younger man actually works as much as possible to get the church's affairs straightened up.

That's a situation, not a story, and it's one of the curiosities of Going My Way that it tends to build itself out of situations. The whole movie feels like it's made out of scrappy anecdotes that don't really fit together and aren't trying to; it's just the litany of stuff that happens while O'Malley finds his footing at St. Dominic's. There's the thread where he intervenes in the local gang of ne'er-do-well boys by teaching them how to sing in a choir; there's the thread where he offers life advice and singing instruction to Carol James (Jean Heather, who as fate would have it, also appears in Double Indemnity), a mildly rebellious teen girl who is eventually taken as mistress by Ted Haines, Jr. (James Brown), the son of Ted Haines, Sr. (Gene Lockhart), who's the very landlord that's current making life hell difficult for St. Dominic's, which is deep in debt; there's the thread where he reunites with his former lover and performing partner Jenny Tuffel (Risë Stevens), now a star at the Metropolitan Opera under the stage name Genevieve Linden. These all coalesce around the fact that this is a Bing Crosby vehicle and thus a musical, so the combined forces of an amateur boys choir and the Met end up serving as the path out of debt for the embattled church, along with O'Malley's surprisingly smooth baritone, for a priest.

The greatest strength of Going My Way is that McCarey is happy to let his actors and characters find themselves in the moment. At the level of individual scenes, this is a frequently brilliant human study. Almost certainly the best individual scene comes late in the film, as Haines père finds the nest where his son has been keeping Carol, and over the course of a languid, unforced exchange of dialogue (so unforced that, in fact, old man Haines end up seeming a little bit slow on the uptake), and in several long but takes that don't make a big deal about themselves, the film floats between moods and tightens the shot scale to grow slowly more intimate until the film suddenly and bluntly slams into the one and only explicit nod to the war going on, bringing a blast of simple realism into what was looking like a melodrama, and giving this shaggy B-plot an anchor in basic humanity. It's a lovely moment that's earnest without being saccharine, and presented with an absolute minimum of fuss.

The other best scenes tend to center around Barry Fitzgerald, giving the only performance in history nominated for two Oscar nominations, as both lead and supporting actor (the rules were immediately changed to make sure it couldn't happen again - and it's ridiculous anyway to describe this as a lead performance). It's one of the most muted screen performances he ever gave, devoid of the ebullient broadness that he was encouraged towards by his most frequent and famous director, John Ford (his performances naturally drift towards broadness in part due to a natural-born Irish accent that makes him sound like a cartoon leprechaun); there's a sad fatigue to many of his scenes, a way of just slightly delaying his reactions and delivering his lines just a bit lower than his scene partners. In what is generally claimed to be a lightheated, upbeat film to raise your spirits, Fitzgerald's scenes consistently bring it back to the meat of the scenario: he has taken this to be a film about the anxiety of a traditional priest overwhelmed by the amount of pragmatic engagement with modern systems in order to keep his church running, and played it accordingly. His scenes with Crosby are in some way the strangest in the film, bringing our attention back around to the matter of being a bureaucrat in the Catholic hierarchy from wherever else they have gone, and they also generally tend to be the most interesting.

McCarey's approach is a double-eged sword, though. He's so interested in the individual moments that Going My Way feels like it has no larger-scale structure than the individual scene. The result is a film that feels like a collage of briefly-glimpsed passages from several different movies - some funny, some sad, some sweet and cute, but all rather pointedly different. The film lacks any sort of urgency: at one point, for example, we get to watch for a couple of minutes as Jenny performs in Carmen. And look, I like Carmen, and it's a thrill to see Stevens, one of her generation's foremost Carmens, recorded on film for even a fragment of a scene. But Jenny is barely even a secondary character, and there's not a single thing that watching her sing "L'amour est un oiseau rebelle" does for the film other than let us enjoy good opera performed well. Which isn't really what we're here for. Multiply that tendency across every moment in the movie, and you end up with an extremely slow-moving 126 minutes that seems to be made up almost entirely of unrelated notions.

This might work with a more dynamic central figure, but O'Malley finds Crosby at his most sedate and dispassionate. As with everything else here, there are moments that shine: watching O'Malley explain how he would interpret a song to Carol feels like we've been let into Crosby's own process rather than the character's, and the crisp, thoughtful professionalism he displays here is the liveliest and most alert he is in the entire film. Far more often, though, he's gliding through scenes as smoothly as he sings, and with as easy an effect on the viewer. It's a relaxed, "I'm just here hanging out" performance, the kind you get to do when you're a charismatic movie star, and I've liked it in plenty of other movies. But Going My Way needs help to make it work: it needs a version of O'Malley who's actively trying to force the subplots forward towards a shared endpoint. Crosby's just letting things happen, beatifically waiting for plot points to find him and for his scene partners to find the emotional weight of a scene so he can join them there. It's a pleasant, easygoing bit of screen acting, but it's a bad fit for a film that's already basically shapeless and meandering. Going My Way bets everything on the audience finding it to be an agreeable movie about decent people doing nice things, and it is, but it's so sluggish as to come awfully close to smothering all of that and leaving behind nothing but tacky, sleepy sentimentality.

Anyway, I have no answers to the question of why, exactly, Going My Way should be one of the defining films of 1940s popular cinema, but it does seem important to acknowledge that it most certainly was. This puts a certain pressure on it that it's not really built to endure - this is one of the quintessential "that won Best Picture?" movies, and not only because it beat Double Indemnity, one of the most enduring films of the decade. Lots of movies beat better movies for Oscars, and plenty of downright shitty movies have been dubiously named Best Picture, but even something as abject as 1937's The Life of Emile Zola still makes sense, cynically: it rather strenuously declares its importance and weight and demands respect. One of the most salient characteristics of Going My Way is that it doesn't do that at all; it's very easygoing and light and while it probably doesn't mind if we walk out feeling like we've learned something, it's not really going out of its way to teach us anything.

Even the existence of the film is something of a "sure, why not" story. Director and producer Leo McCarey, a devout Irish-American Catholic, had a story idea he badly wanted to make into film, about a progressive priest and a strait-laced nun who butt heads over how best to help secure the future of a run-down parochial school in New York. That idea was turned into a screenplay by Dudley Nichols, under the name The Bells of St. Mary's, and McCarey tried his god-damnedest gosh-darnedest to get it made, but none of the studios would bite. For reason that I do not quite understand, however, Paramount agreed to make a different film about the same progressive priest, and so McCarey came up with an almost identical story replacing the nun with another priest, and having writers Frank Butler and Frank Cavett work it into a screenplay. After the success of Going My Way, McCarey got to make The Bells of St. Mary's, which was an even bigger hit, as well as being the better film, and there's some bits of mildly amusing trivia that centers on it that I'll go into at such time as I get around to reviewing it. The point being, Going My Way was relatively an afterthought, the movie McCarey made because he couldn't make the "real" one.

That's a shitty way of putting it, and it's not like Going My Way is some slopped-together hackwork. Indeed, at its best, the film ably showcases McCarey's excellent gift for stepping back and watching human behavior, ungainly and interesting as it can be (among other things, it is shockingly forthright about the existence of sex and prostitution). The film focuses on Father Chuck O'Malley (Crosby), who we know is a relaxed, modern sort because he goes by "Chuck"; he's been called from St. Louis to put some order into St. Dominic's in New York, a place that has been lovingly but ineptly run for 45 years by Father Fitzgibbon (Barry Fitzgerald). To save Fitzgibbon's pride, and avoid any squabbling, the bishop and O'Malley have agreed to let the old man suppose that O'Malley is just his assistant, while the younger man actually works as much as possible to get the church's affairs straightened up.

That's a situation, not a story, and it's one of the curiosities of Going My Way that it tends to build itself out of situations. The whole movie feels like it's made out of scrappy anecdotes that don't really fit together and aren't trying to; it's just the litany of stuff that happens while O'Malley finds his footing at St. Dominic's. There's the thread where he intervenes in the local gang of ne'er-do-well boys by teaching them how to sing in a choir; there's the thread where he offers life advice and singing instruction to Carol James (Jean Heather, who as fate would have it, also appears in Double Indemnity), a mildly rebellious teen girl who is eventually taken as mistress by Ted Haines, Jr. (James Brown), the son of Ted Haines, Sr. (Gene Lockhart), who's the very landlord that's current making life hell difficult for St. Dominic's, which is deep in debt; there's the thread where he reunites with his former lover and performing partner Jenny Tuffel (Risë Stevens), now a star at the Metropolitan Opera under the stage name Genevieve Linden. These all coalesce around the fact that this is a Bing Crosby vehicle and thus a musical, so the combined forces of an amateur boys choir and the Met end up serving as the path out of debt for the embattled church, along with O'Malley's surprisingly smooth baritone, for a priest.

The greatest strength of Going My Way is that McCarey is happy to let his actors and characters find themselves in the moment. At the level of individual scenes, this is a frequently brilliant human study. Almost certainly the best individual scene comes late in the film, as Haines père finds the nest where his son has been keeping Carol, and over the course of a languid, unforced exchange of dialogue (so unforced that, in fact, old man Haines end up seeming a little bit slow on the uptake), and in several long but takes that don't make a big deal about themselves, the film floats between moods and tightens the shot scale to grow slowly more intimate until the film suddenly and bluntly slams into the one and only explicit nod to the war going on, bringing a blast of simple realism into what was looking like a melodrama, and giving this shaggy B-plot an anchor in basic humanity. It's a lovely moment that's earnest without being saccharine, and presented with an absolute minimum of fuss.

The other best scenes tend to center around Barry Fitzgerald, giving the only performance in history nominated for two Oscar nominations, as both lead and supporting actor (the rules were immediately changed to make sure it couldn't happen again - and it's ridiculous anyway to describe this as a lead performance). It's one of the most muted screen performances he ever gave, devoid of the ebullient broadness that he was encouraged towards by his most frequent and famous director, John Ford (his performances naturally drift towards broadness in part due to a natural-born Irish accent that makes him sound like a cartoon leprechaun); there's a sad fatigue to many of his scenes, a way of just slightly delaying his reactions and delivering his lines just a bit lower than his scene partners. In what is generally claimed to be a lightheated, upbeat film to raise your spirits, Fitzgerald's scenes consistently bring it back to the meat of the scenario: he has taken this to be a film about the anxiety of a traditional priest overwhelmed by the amount of pragmatic engagement with modern systems in order to keep his church running, and played it accordingly. His scenes with Crosby are in some way the strangest in the film, bringing our attention back around to the matter of being a bureaucrat in the Catholic hierarchy from wherever else they have gone, and they also generally tend to be the most interesting.

McCarey's approach is a double-eged sword, though. He's so interested in the individual moments that Going My Way feels like it has no larger-scale structure than the individual scene. The result is a film that feels like a collage of briefly-glimpsed passages from several different movies - some funny, some sad, some sweet and cute, but all rather pointedly different. The film lacks any sort of urgency: at one point, for example, we get to watch for a couple of minutes as Jenny performs in Carmen. And look, I like Carmen, and it's a thrill to see Stevens, one of her generation's foremost Carmens, recorded on film for even a fragment of a scene. But Jenny is barely even a secondary character, and there's not a single thing that watching her sing "L'amour est un oiseau rebelle" does for the film other than let us enjoy good opera performed well. Which isn't really what we're here for. Multiply that tendency across every moment in the movie, and you end up with an extremely slow-moving 126 minutes that seems to be made up almost entirely of unrelated notions.

This might work with a more dynamic central figure, but O'Malley finds Crosby at his most sedate and dispassionate. As with everything else here, there are moments that shine: watching O'Malley explain how he would interpret a song to Carol feels like we've been let into Crosby's own process rather than the character's, and the crisp, thoughtful professionalism he displays here is the liveliest and most alert he is in the entire film. Far more often, though, he's gliding through scenes as smoothly as he sings, and with as easy an effect on the viewer. It's a relaxed, "I'm just here hanging out" performance, the kind you get to do when you're a charismatic movie star, and I've liked it in plenty of other movies. But Going My Way needs help to make it work: it needs a version of O'Malley who's actively trying to force the subplots forward towards a shared endpoint. Crosby's just letting things happen, beatifically waiting for plot points to find him and for his scene partners to find the emotional weight of a scene so he can join them there. It's a pleasant, easygoing bit of screen acting, but it's a bad fit for a film that's already basically shapeless and meandering. Going My Way bets everything on the audience finding it to be an agreeable movie about decent people doing nice things, and it is, but it's so sluggish as to come awfully close to smothering all of that and leaving behind nothing but tacky, sleepy sentimentality.