Blockbuster History: Bullet trains

To wrap up the summer movie season, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to a wide-release film from the last few weeks. From August 5: Bullet Train takes place in the highly tense environment of a metal tube screaming through the Japanese country side at several dozen kilometers per hour. It's no surprise that such a location has attracted filmmakers before now.

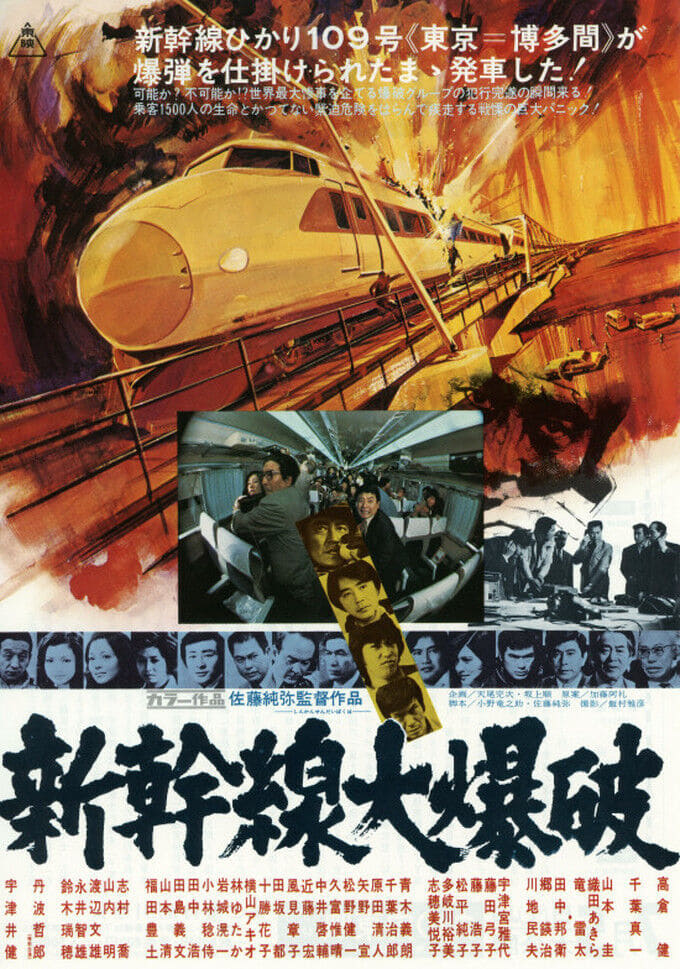

There are two cuts of the 1975 Japanese thriller The Bullet Train, directed by Sato Jun'ya from a screenplay he wrote with Ono Ryunosuke. The one that Toei, the production company, sent out to the world at large was 115 minutes; the one released in Japan was 152 minutes. Both have been released around the world, but in the HD era, the longer Japanese cut has mostly become the "default", and this is as it should be; slicing apart a finished movie because of some concerns about whether or not any given audience can deal with it is a low, low thing to do. And this is true even though the 152-minute version of The Bullet Train would absolutely benefit from being much closer to 115 minutes.

I doubt very much that the actually-existing 115-minute cut would be the way to get there, though. Most of what is best about The Bullet Train has very little to do with its action-sounding hook: somebody has planted a bomb on one of the high-speed trains running on the Shinkansen, the trans-Japanese network of high-tech railways that had gone into operation in the mid-1960s (the film's Japanese title translates as something close to Big Shinkansen Explosion). If the train in question, Hikari 109, drops below 80 KPH, the bomb will explode. And before you ask, this was the avowed inspiration for the 1994 Hollywood action film Speed, though I believe Speed's writer, Graham Yost, had not actually seen The Bullet Train before writing the movie, and I don't mean that it the snarky sense that Speed is a dumb, coarse American action picture instead of a wise, subtle Japanese character drama. I mean he literally hadn't read it, if I follow the story correctly.

Though, comparatively, Speed is a dumb, coarse American picture while The Bullet Train is a Japanese character drama, which gets back the point I was making about the two cuts. The best material in this film is almost never its ostensible selling point, which is the high-speed bomb-defusing thrills. The best material is the accumulated scenes of the bomber, Okita Tetsuo (Takakura Ken), sitting in sullen loneliness as he ponders what he's done. Not having seen the 115-minute cut, I can't say with authority that this is obviously some of the material that you'd cut, if you were trying to make this as appealing as possible to a global audience. But I have my very strong suspicions. And losing this material would make The Bullet Train a much less rich experience indeed.

Takakura was, during his career, one of the most estimable actors in the Japanese film industry; he was the first actor to win the Japanese Academy Prize four times (a number that has been tied by two women and four other men, but never surpassed), including the very first time that award was given out, in 1977; he was the only person to win that prize four times in the category of Best Lead Actor. But he's an obscure figure to Western audiences: The Bullet Train and 1977's The Yellow Handkerchief probably come the closest to being well-known in the West, and I have very little doubt that most Americans who've seen him have seen one of the three U.S. productions set in Japan where he shows up as "the main Japanese guy": 1974's The Yakuza, 1989's Black Rain, and 1992's Mr. Baseball. Not a worthy fate for a man who is, if my newfound sample size of one is any indication, a tremendously talented actor with jaw-dropping screen presence. Okita has already been written as the film's de facto main character: the scenes of law enforcement officials and Shinkansen technicians gathering in offices to discuss what to do are designed to make sure that we can largely recognise faces and sort them roughly into a hierarchy, but the only one who really comes across as a "character" is Kuramochi (Utsui Ken), the company director who ends up serving as the public face of the attempt to communicate with Okita; the next closest is Miyashita (Watanabe Fumio), the company's security head, but he's much more then most successful example of "faces we can largely recognise" than a psychological figure in his own right. The 1500 passengers on the train and the employees running it are even more conceived of as basically just a mass of humans; conductor Aoki ("Sonny" Chiba Shin'ichi) unquestionably makes the most impression, both because he's got the most distinctive and plot-consequential job, and because he's played by Sonny Chiba, in literally the first possible year for the presence of Chiba to be a reflection of his fame and not because he was a working character actor. But if you were to watch The Bullet Train because you wanted a good Sonny Chiba vehicle, you would be devastated with disappointment, unless you think "he steadily and with great concentration maneuvers the lever controlling the train's speed down just a few notches" is exciting on the same level as "he literally punches a dude's face off of his skull".

This is, none of it, a problem with The Bullet Train; on the contrary, setting up Okita as the only truly distinct character in the entire film is the most interesting single choice the writers make, doing wonderfully offbeat things to the movie's tone and mood. On the one hand - the hand where we find all of the scenes of meetings, of looking fearfully at boards of yellow lights, of screaming back and forth about diagrams - this is a story about the power of Japanese bureaucracy to identify and then solve problems; on the other hand, this is the story about a man who has fallen out of the system and is lost, lost beyond hope of being found. The contrast between Okita and the busy mass of people trying to stop him is the movie, and while I'd need to be more up on my Japanese sociology to really be able to explain what's going on here, I do know that in 1975, the Economic Miracle of the 1960s had only slowed from "unprecedented growth" to "very good growth". I also know that the Shinkansen trains were one of the many symbols of the speed and success with which post-war Japan had reinvented itself as one of the most sophisticated, forward-moving economies and cultures in the developed world. Okita is presented as a man who has missed out on all of that. He's gambled away his money, his wife (Utsunomiya Masayo) has left him and taken their son, he's all washed up. And so, in a fit of desperation, he decides that his last chance to make money will be by taking as hostage one of those exact same symbols of the country's meteoric rise that has left him far behind, too far to ever catch up.

The film strikes an impressively narrow balance in portraying Okita. He's pitiable without being sympathetic; the script takes pains to make sure that we see his callous indifference to the 1500 lives he's gambling with, particularly in how it treats the mid-film development that one of the passengers, a pregnant woman, miscarries from the stress, and how this fact gently dissipates against the brick wall of unblinking conviction that Takakura has built around Okita. At the same time, the unmistakable, omnipresent individuality of Okita makes it hard not to think of him as the Last True Man in world racing towards the future so fast that it has left behind some of its human feeling. And Takakura makes this come through as well, making Okita a well-etched individual, smart but broken, taciturn as way to keep from weeping.

The version of The Bullet Train all about spending time with this fascinatingly humane and terrifyingly misguided individual is actively great. The version of The Bullet Train about keeping a bullet train from blowing up is... intermittently great, I guess. It gets better as it goes along, until the last 40 minutes are a virtually non-stop run of agonisingly tense moments, with the jerry-rigged efforts to deal with the bomb feeling all the more precarious because of how sweaty and tired all of the characters have gotten by this point in their very long, horrible day. I'll say this much for that running time: there's a ton of material in this film, and all of it benefits from a sense of exhausting duration. All of it would, I think, still receive that benefit at only two hours. But no matter: the film eventually works itself up to being a suffocatingly nervy thriller, and manages to keep it up even once the final 15 minutes prove to be entirely different than anything else we've seen up to that point.

Sato keeps all of this moving crisply; it's a kinetic movie, constantly worrying itself in form of crash zooms and fast pans and jittery handheld camerawork. It freely moves between the present and flashbacks without ever doing much to mark it out, so the whole thing demands a great deal of alertness from us, paying attention to the shifts in scenes to place ourselves. A few times, always linked to Okita's stormy mental state, it throws out a blast of surreal stylistic exuberance. The 152 minutes are not, that is to say, slow. But they are often unproductive, and this is the biggest problem with the film: it mistakes, somewhat, "collective decisionmaking is great, but it leaves the powers-that-be in a tough spot when they need to take quick action" with "the movie is slow and repetitive because bureaucracy is slow and repetitive". It's still a thriller, after all, and could do with being a bit more thrilling. But enough of this works - and what works comes along with such perfect timing - that I think it's worth cutting the film a bit of slack. As if it needed to be more slack!! I'm sorry, that was mean.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

There are two cuts of the 1975 Japanese thriller The Bullet Train, directed by Sato Jun'ya from a screenplay he wrote with Ono Ryunosuke. The one that Toei, the production company, sent out to the world at large was 115 minutes; the one released in Japan was 152 minutes. Both have been released around the world, but in the HD era, the longer Japanese cut has mostly become the "default", and this is as it should be; slicing apart a finished movie because of some concerns about whether or not any given audience can deal with it is a low, low thing to do. And this is true even though the 152-minute version of The Bullet Train would absolutely benefit from being much closer to 115 minutes.

I doubt very much that the actually-existing 115-minute cut would be the way to get there, though. Most of what is best about The Bullet Train has very little to do with its action-sounding hook: somebody has planted a bomb on one of the high-speed trains running on the Shinkansen, the trans-Japanese network of high-tech railways that had gone into operation in the mid-1960s (the film's Japanese title translates as something close to Big Shinkansen Explosion). If the train in question, Hikari 109, drops below 80 KPH, the bomb will explode. And before you ask, this was the avowed inspiration for the 1994 Hollywood action film Speed, though I believe Speed's writer, Graham Yost, had not actually seen The Bullet Train before writing the movie, and I don't mean that it the snarky sense that Speed is a dumb, coarse American action picture instead of a wise, subtle Japanese character drama. I mean he literally hadn't read it, if I follow the story correctly.

Though, comparatively, Speed is a dumb, coarse American picture while The Bullet Train is a Japanese character drama, which gets back the point I was making about the two cuts. The best material in this film is almost never its ostensible selling point, which is the high-speed bomb-defusing thrills. The best material is the accumulated scenes of the bomber, Okita Tetsuo (Takakura Ken), sitting in sullen loneliness as he ponders what he's done. Not having seen the 115-minute cut, I can't say with authority that this is obviously some of the material that you'd cut, if you were trying to make this as appealing as possible to a global audience. But I have my very strong suspicions. And losing this material would make The Bullet Train a much less rich experience indeed.

Takakura was, during his career, one of the most estimable actors in the Japanese film industry; he was the first actor to win the Japanese Academy Prize four times (a number that has been tied by two women and four other men, but never surpassed), including the very first time that award was given out, in 1977; he was the only person to win that prize four times in the category of Best Lead Actor. But he's an obscure figure to Western audiences: The Bullet Train and 1977's The Yellow Handkerchief probably come the closest to being well-known in the West, and I have very little doubt that most Americans who've seen him have seen one of the three U.S. productions set in Japan where he shows up as "the main Japanese guy": 1974's The Yakuza, 1989's Black Rain, and 1992's Mr. Baseball. Not a worthy fate for a man who is, if my newfound sample size of one is any indication, a tremendously talented actor with jaw-dropping screen presence. Okita has already been written as the film's de facto main character: the scenes of law enforcement officials and Shinkansen technicians gathering in offices to discuss what to do are designed to make sure that we can largely recognise faces and sort them roughly into a hierarchy, but the only one who really comes across as a "character" is Kuramochi (Utsui Ken), the company director who ends up serving as the public face of the attempt to communicate with Okita; the next closest is Miyashita (Watanabe Fumio), the company's security head, but he's much more then most successful example of "faces we can largely recognise" than a psychological figure in his own right. The 1500 passengers on the train and the employees running it are even more conceived of as basically just a mass of humans; conductor Aoki ("Sonny" Chiba Shin'ichi) unquestionably makes the most impression, both because he's got the most distinctive and plot-consequential job, and because he's played by Sonny Chiba, in literally the first possible year for the presence of Chiba to be a reflection of his fame and not because he was a working character actor. But if you were to watch The Bullet Train because you wanted a good Sonny Chiba vehicle, you would be devastated with disappointment, unless you think "he steadily and with great concentration maneuvers the lever controlling the train's speed down just a few notches" is exciting on the same level as "he literally punches a dude's face off of his skull".

This is, none of it, a problem with The Bullet Train; on the contrary, setting up Okita as the only truly distinct character in the entire film is the most interesting single choice the writers make, doing wonderfully offbeat things to the movie's tone and mood. On the one hand - the hand where we find all of the scenes of meetings, of looking fearfully at boards of yellow lights, of screaming back and forth about diagrams - this is a story about the power of Japanese bureaucracy to identify and then solve problems; on the other hand, this is the story about a man who has fallen out of the system and is lost, lost beyond hope of being found. The contrast between Okita and the busy mass of people trying to stop him is the movie, and while I'd need to be more up on my Japanese sociology to really be able to explain what's going on here, I do know that in 1975, the Economic Miracle of the 1960s had only slowed from "unprecedented growth" to "very good growth". I also know that the Shinkansen trains were one of the many symbols of the speed and success with which post-war Japan had reinvented itself as one of the most sophisticated, forward-moving economies and cultures in the developed world. Okita is presented as a man who has missed out on all of that. He's gambled away his money, his wife (Utsunomiya Masayo) has left him and taken their son, he's all washed up. And so, in a fit of desperation, he decides that his last chance to make money will be by taking as hostage one of those exact same symbols of the country's meteoric rise that has left him far behind, too far to ever catch up.

The film strikes an impressively narrow balance in portraying Okita. He's pitiable without being sympathetic; the script takes pains to make sure that we see his callous indifference to the 1500 lives he's gambling with, particularly in how it treats the mid-film development that one of the passengers, a pregnant woman, miscarries from the stress, and how this fact gently dissipates against the brick wall of unblinking conviction that Takakura has built around Okita. At the same time, the unmistakable, omnipresent individuality of Okita makes it hard not to think of him as the Last True Man in world racing towards the future so fast that it has left behind some of its human feeling. And Takakura makes this come through as well, making Okita a well-etched individual, smart but broken, taciturn as way to keep from weeping.

The version of The Bullet Train all about spending time with this fascinatingly humane and terrifyingly misguided individual is actively great. The version of The Bullet Train about keeping a bullet train from blowing up is... intermittently great, I guess. It gets better as it goes along, until the last 40 minutes are a virtually non-stop run of agonisingly tense moments, with the jerry-rigged efforts to deal with the bomb feeling all the more precarious because of how sweaty and tired all of the characters have gotten by this point in their very long, horrible day. I'll say this much for that running time: there's a ton of material in this film, and all of it benefits from a sense of exhausting duration. All of it would, I think, still receive that benefit at only two hours. But no matter: the film eventually works itself up to being a suffocatingly nervy thriller, and manages to keep it up even once the final 15 minutes prove to be entirely different than anything else we've seen up to that point.

Sato keeps all of this moving crisply; it's a kinetic movie, constantly worrying itself in form of crash zooms and fast pans and jittery handheld camerawork. It freely moves between the present and flashbacks without ever doing much to mark it out, so the whole thing demands a great deal of alertness from us, paying attention to the shifts in scenes to place ourselves. A few times, always linked to Okita's stormy mental state, it throws out a blast of surreal stylistic exuberance. The 152 minutes are not, that is to say, slow. But they are often unproductive, and this is the biggest problem with the film: it mistakes, somewhat, "collective decisionmaking is great, but it leaves the powers-that-be in a tough spot when they need to take quick action" with "the movie is slow and repetitive because bureaucracy is slow and repetitive". It's still a thriller, after all, and could do with being a bit more thrilling. But enough of this works - and what works comes along with such perfect timing - that I think it's worth cutting the film a bit of slack. As if it needed to be more slack!! I'm sorry, that was mean.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Categories: blockbuster history, crime pictures, japanese cinema, thrillers