Win or die

A review requested by Brian, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

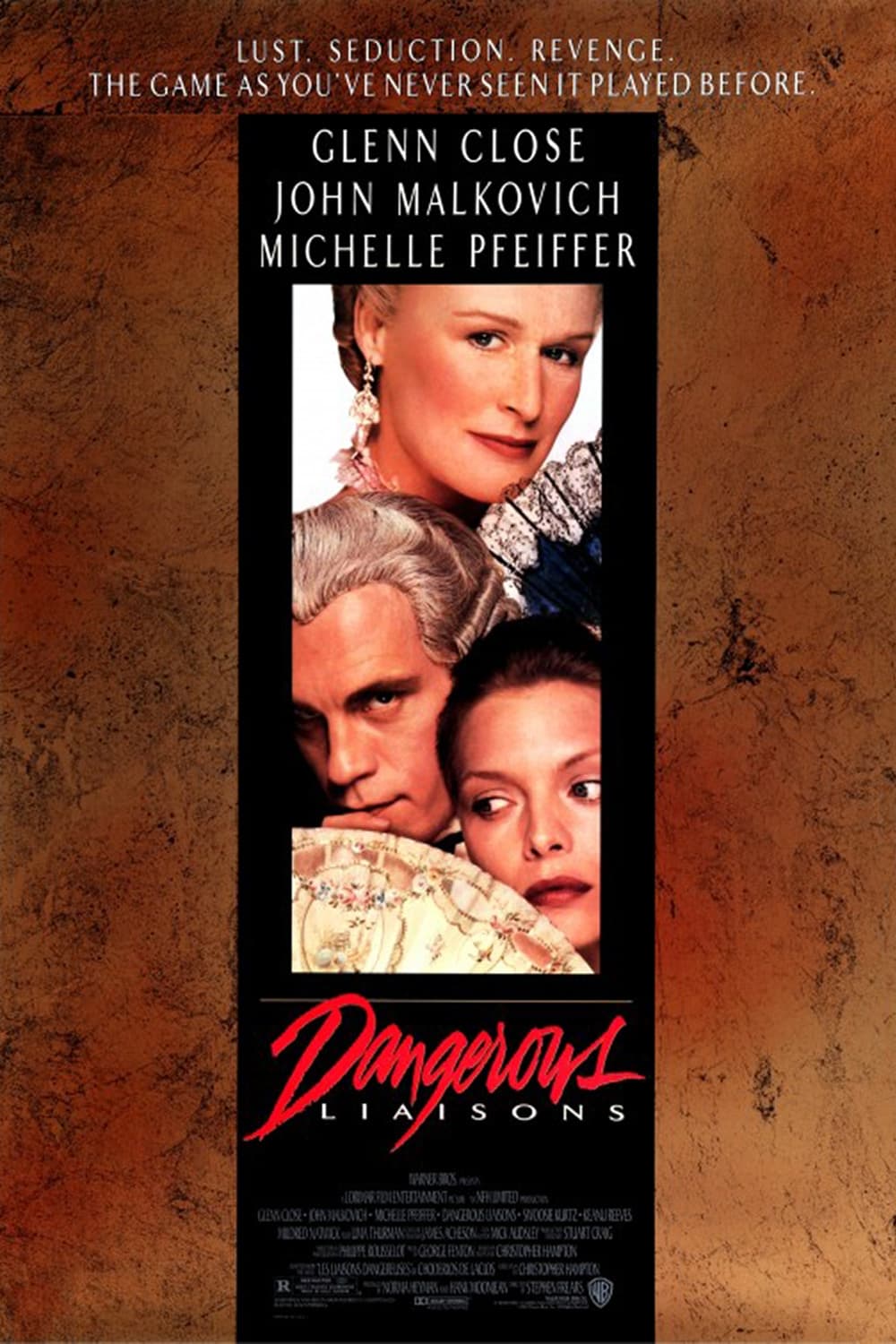

The costume drama is a genre as old as the movies themselves (The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots was made in 1895, and I don't actually know if it was the very first example of the form), and has literally never gone out of style in all the years that cinema has existed. But like any other long-lived genre, it has its ebbs and flows, its periods of strength and it long stretches of mediocrity, and I would be inclined to say that period from around the mid-1980s to sometime in the second half of the 1990s was a particular golden age for the form (if we had to bracket it, I'd probably use 1984's Amadeus and 1998's Shakespeare in Love). And among the defining films of that golden age, I think, we would have to include Dangerous Liaisons, a 1988 adaptation by Christopher Hampton of his own hit play itself adapted from the 1782 novel Les Liaisons dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. And that novel has enjoyed quite a robust life at the movies - Dangerous Liaisons was itself the first of new fewer than three English-language feature adaptations - but this particularly adaptation is my favorite of the ones I've seen, for a pretty straightforward reason: it is the most excessively meanspirited and cruel.

For cruelty is, in this case, very much the point (heck, one of those three English adaptations - the one that pulls its punches the most, ironically - is titled Cruel Intentions). The degree to which the original novel is a sharp-toothed satire of the depraved boredom of wealthy aristocrats in Ancien Régime Paris, versus how much it's just a salacious wallow in their depravity that accidentally seemed to become a satire due to the lucky timing of a revolution only seven years after it came out, has been a matter of debate amongst literary scholars for more than 200 years at this point, and I'm not in a position to offer an opinion. I haven't even read the book in the original French. But I can say this, at least: the two main characters, the Marquise de Merteuil (Glenn Close) and the Vicomte de Valmont (John Malkovich) are unambiguously and unmixedly disgusting human beings. They are vicious beasts who destroy and torment other people not even for fun, because fun implies something more active and upbeat than what we see. They do it because they are desperately terrified of ever feeling bored. And the story forces us to identify with them, since we have no other options: we know exactly what they know and it's a ton more than any other main character knows, and so we get to just hang out watching them be the most appalling monsters you can imagine, and the dirty trick is that it's a hell of a lot of fun. Because in addition to being horrifyingly unmoral, Merteuil and Valmon Sot are extremely intelligent, well-read, and quick-witted, and it is a pleasure, no two ways about it, to listen to their immaculately-crafted words as they execute their immaculately-crafted plots. So in a sense, the more venomous these snakes can get, the more delightful Dangerous Liaisons gets, and that is the moral trap Laclos set way back in the 1780s, and which we continue to fall into right up the present day.

Dangerous Liaisons, 1988 edition, does as fine a job baiting that trap as I can imagine any adaptation in English ever doing. First, it has Hampton's breezy adaptation, porting over many fine and cutting lines from the book; second, it has Stephen Frears, who was at this point still at the point of being an exciting new British director making interesting and thorny movies like My Beautiful Laundrette, Prick Up Your Ears, and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, and indeed it was mostly likely Dangerous Liaisons itself that triggered his career transition to become a maker of handsome, literary-ish period Oscarbait. That didn't really take hold until the 2000s, though, and in the meantime, Frears mostly remained a smart and confident filmmaker whose style was mostly pretty quiet and unglamorous, while being still kind of exactly perfect for providing the right visuals at the right time. Dangerous Liaisons, for example, opens with a terrific cross-cutting credits sequence of Merteuil and Valmont getting ready for war, i.e. dressing themselves in the elaborate multi-layered head-to-toe fashion of pre-Revolutionary France, and it's well-done, but what makes it extremely clever is that we start by seeing Merteuil's face (echoed when her face will prove to also be the last thing we see), and her half of the cross-cutting structure always lets us see her expressions as she's dressed and made up by her ladies in waiting; while Valmont is given one of those "we're conspicuously not seeing this character's face" sequences that only ends once the very final finishing touches have been laid in, and he pulls an inhuman, cone-shaped face protector off, revealing Malkovich staring into the camera with dead lizard eyes. And this silently ends up playing into the character dynamics for the rest of the movie. Merteuil, limited by the domineering masculinity of her society, must necessarily rely on her own beauty and sex appeal as her only weapon; Valmont has access to the forms and power dynamics of that society more directly. Ergo, a focus on the face versus a focus on the costume.

In general, Frears can be counted on to frame the action as a matter of tense stand-offs between close-ups; the film's Oscar-winning production design, by Stuart Craig, looks exquisite, but the film isn't really selling it. This is not costume drama as spectacle, not really; the lavish sets and costumes (which also won an Oscar for James Acheson) and hair and make-up aren't the stars of the show, they're the necessary work being done to frame a long-dead (and good riddance!) culture, so we can understand how that culture frames the story, even as Hampton (who won the film's third Oscar, since I'm mentioning it) makes the characters feel bright and alive. Dangerous Liaisons is both about behavior in an exceptionally specific, bounded context, and about a kind of human ugliness that transcends eras, and which comes out in the extraordinary performances of Close, Malkovich, and Michelle Pfeiffer, as the primary target of Valmont's plotting, and the subject of a hideous bet between the two anti-heroes. They're the best of a strong ensemble; Uma Thurman, in her big break-out role, isn't great at modulating between "dewy ingenue" and "sex-hungry moron", and as Thurman's mother, Swoosie Kurtz, though she's fantastic at capturing the stress of living in a society dominated by exacting physical presentations of behavior, hasn't entirely pinned down her accent. Keanu Reeves, as the charming, hunky pawn that Merteuil is using to humiliate a few of her rivals simultaneously, is just plain bad - I'd love to have something nuanced to say about him, but there really isn't anything. It's a role outside of his skill set, and it's not big or important enough that he can really break anything, but he's just flat-out bad, at physical carriage and accent work and line delivery and exuding any kind of sexuality, in this story that's all about different ways of being horny, generally to bad ends.

Dangerous Liaisons, the movie, is generally a bit less horny and bit more angry than the book (I cannot speak of the intermediate play); it's primarily focused on how sex is used as a weapon by bored sociopaths, as part of a broader game of maneuvering through the elaborate social codes of 1780s France. That's really the main focus of Hampton's script, and accordingly Frears's directing of the actors: the sheer amount of calculation it takes to just exist in this world, and how it almost inevitably produces Merteuils and Valmonts, even if not everyone is going to become like them. But they are perfectly evolved into this world, and Close and Malkovich's work reflects this, especially Close's; it's my very favorite of all her screen performances, in no small part because how effortlessly she seems to sink into the environments - she wears her costumes, stands on the sets, and addresses the camera, all like she's an organic part of the world, ethereally comfortable and perfect there. It's part of what makes the film's final scene feel a bit jarring; in all incarnations, Les Liaisons dangereuses needs Merteuil to suffer at the end, like the rest of the cast suffers, but the way her suffering manifests here feels oddly unfair, like she's getting jeered at simply for being more perfect than everybody else, and Close's iceberg expression in the last shot gives one the sense that she feels that way too. It's a brilliant final performance beat, at least, even if I have questions as to whether it's as good a final dramatic beat.

But otherwise, this is a wonderful clockwork mechanism, moving its characters through an always-changing maze of interpersonal hostilities, letting us watch along with the puppetmasters as they jerk along the rest of the characters, so it remains delightfully clear what traps are being set and sprung no matter how convoluted they get. It gets a little pacy sometime in the second half, largely by getting too bogged down on the Thurman-Reeves material, and there are multiple stretches where Close is kept offscreen for too long (and not just in the sense that "Glenn Close isn't onscreen right this second" is always kind of too long, for my tastes, with this performance). But its marriage of story beats with the beautifully constructed setting and the meticulous sonic framework of George Fenton's Classical-flavored score is always done very well, even when the story beats themselves are of less interest, and the film in general keeps a delicate balance between "all this hedonism is despicable" and "all this hedonism is delectable", from its quippy script through to its performances. For all that this looks like an overly-manicured prestige picture, and it has the Oscar and BAFTA nomination hauls to go along with it, Dangeous Liaisons is also just, like, a really good movie, putting a handsome gloss on sordid material in a way that might not quite feel "dangerous", but is at least extremely bracing.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

The costume drama is a genre as old as the movies themselves (The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots was made in 1895, and I don't actually know if it was the very first example of the form), and has literally never gone out of style in all the years that cinema has existed. But like any other long-lived genre, it has its ebbs and flows, its periods of strength and it long stretches of mediocrity, and I would be inclined to say that period from around the mid-1980s to sometime in the second half of the 1990s was a particular golden age for the form (if we had to bracket it, I'd probably use 1984's Amadeus and 1998's Shakespeare in Love). And among the defining films of that golden age, I think, we would have to include Dangerous Liaisons, a 1988 adaptation by Christopher Hampton of his own hit play itself adapted from the 1782 novel Les Liaisons dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. And that novel has enjoyed quite a robust life at the movies - Dangerous Liaisons was itself the first of new fewer than three English-language feature adaptations - but this particularly adaptation is my favorite of the ones I've seen, for a pretty straightforward reason: it is the most excessively meanspirited and cruel.

For cruelty is, in this case, very much the point (heck, one of those three English adaptations - the one that pulls its punches the most, ironically - is titled Cruel Intentions). The degree to which the original novel is a sharp-toothed satire of the depraved boredom of wealthy aristocrats in Ancien Régime Paris, versus how much it's just a salacious wallow in their depravity that accidentally seemed to become a satire due to the lucky timing of a revolution only seven years after it came out, has been a matter of debate amongst literary scholars for more than 200 years at this point, and I'm not in a position to offer an opinion. I haven't even read the book in the original French. But I can say this, at least: the two main characters, the Marquise de Merteuil (Glenn Close) and the Vicomte de Valmont (John Malkovich) are unambiguously and unmixedly disgusting human beings. They are vicious beasts who destroy and torment other people not even for fun, because fun implies something more active and upbeat than what we see. They do it because they are desperately terrified of ever feeling bored. And the story forces us to identify with them, since we have no other options: we know exactly what they know and it's a ton more than any other main character knows, and so we get to just hang out watching them be the most appalling monsters you can imagine, and the dirty trick is that it's a hell of a lot of fun. Because in addition to being horrifyingly unmoral, Merteuil and Valmon Sot are extremely intelligent, well-read, and quick-witted, and it is a pleasure, no two ways about it, to listen to their immaculately-crafted words as they execute their immaculately-crafted plots. So in a sense, the more venomous these snakes can get, the more delightful Dangerous Liaisons gets, and that is the moral trap Laclos set way back in the 1780s, and which we continue to fall into right up the present day.

Dangerous Liaisons, 1988 edition, does as fine a job baiting that trap as I can imagine any adaptation in English ever doing. First, it has Hampton's breezy adaptation, porting over many fine and cutting lines from the book; second, it has Stephen Frears, who was at this point still at the point of being an exciting new British director making interesting and thorny movies like My Beautiful Laundrette, Prick Up Your Ears, and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, and indeed it was mostly likely Dangerous Liaisons itself that triggered his career transition to become a maker of handsome, literary-ish period Oscarbait. That didn't really take hold until the 2000s, though, and in the meantime, Frears mostly remained a smart and confident filmmaker whose style was mostly pretty quiet and unglamorous, while being still kind of exactly perfect for providing the right visuals at the right time. Dangerous Liaisons, for example, opens with a terrific cross-cutting credits sequence of Merteuil and Valmont getting ready for war, i.e. dressing themselves in the elaborate multi-layered head-to-toe fashion of pre-Revolutionary France, and it's well-done, but what makes it extremely clever is that we start by seeing Merteuil's face (echoed when her face will prove to also be the last thing we see), and her half of the cross-cutting structure always lets us see her expressions as she's dressed and made up by her ladies in waiting; while Valmont is given one of those "we're conspicuously not seeing this character's face" sequences that only ends once the very final finishing touches have been laid in, and he pulls an inhuman, cone-shaped face protector off, revealing Malkovich staring into the camera with dead lizard eyes. And this silently ends up playing into the character dynamics for the rest of the movie. Merteuil, limited by the domineering masculinity of her society, must necessarily rely on her own beauty and sex appeal as her only weapon; Valmont has access to the forms and power dynamics of that society more directly. Ergo, a focus on the face versus a focus on the costume.

In general, Frears can be counted on to frame the action as a matter of tense stand-offs between close-ups; the film's Oscar-winning production design, by Stuart Craig, looks exquisite, but the film isn't really selling it. This is not costume drama as spectacle, not really; the lavish sets and costumes (which also won an Oscar for James Acheson) and hair and make-up aren't the stars of the show, they're the necessary work being done to frame a long-dead (and good riddance!) culture, so we can understand how that culture frames the story, even as Hampton (who won the film's third Oscar, since I'm mentioning it) makes the characters feel bright and alive. Dangerous Liaisons is both about behavior in an exceptionally specific, bounded context, and about a kind of human ugliness that transcends eras, and which comes out in the extraordinary performances of Close, Malkovich, and Michelle Pfeiffer, as the primary target of Valmont's plotting, and the subject of a hideous bet between the two anti-heroes. They're the best of a strong ensemble; Uma Thurman, in her big break-out role, isn't great at modulating between "dewy ingenue" and "sex-hungry moron", and as Thurman's mother, Swoosie Kurtz, though she's fantastic at capturing the stress of living in a society dominated by exacting physical presentations of behavior, hasn't entirely pinned down her accent. Keanu Reeves, as the charming, hunky pawn that Merteuil is using to humiliate a few of her rivals simultaneously, is just plain bad - I'd love to have something nuanced to say about him, but there really isn't anything. It's a role outside of his skill set, and it's not big or important enough that he can really break anything, but he's just flat-out bad, at physical carriage and accent work and line delivery and exuding any kind of sexuality, in this story that's all about different ways of being horny, generally to bad ends.

Dangerous Liaisons, the movie, is generally a bit less horny and bit more angry than the book (I cannot speak of the intermediate play); it's primarily focused on how sex is used as a weapon by bored sociopaths, as part of a broader game of maneuvering through the elaborate social codes of 1780s France. That's really the main focus of Hampton's script, and accordingly Frears's directing of the actors: the sheer amount of calculation it takes to just exist in this world, and how it almost inevitably produces Merteuils and Valmonts, even if not everyone is going to become like them. But they are perfectly evolved into this world, and Close and Malkovich's work reflects this, especially Close's; it's my very favorite of all her screen performances, in no small part because how effortlessly she seems to sink into the environments - she wears her costumes, stands on the sets, and addresses the camera, all like she's an organic part of the world, ethereally comfortable and perfect there. It's part of what makes the film's final scene feel a bit jarring; in all incarnations, Les Liaisons dangereuses needs Merteuil to suffer at the end, like the rest of the cast suffers, but the way her suffering manifests here feels oddly unfair, like she's getting jeered at simply for being more perfect than everybody else, and Close's iceberg expression in the last shot gives one the sense that she feels that way too. It's a brilliant final performance beat, at least, even if I have questions as to whether it's as good a final dramatic beat.

But otherwise, this is a wonderful clockwork mechanism, moving its characters through an always-changing maze of interpersonal hostilities, letting us watch along with the puppetmasters as they jerk along the rest of the characters, so it remains delightfully clear what traps are being set and sprung no matter how convoluted they get. It gets a little pacy sometime in the second half, largely by getting too bogged down on the Thurman-Reeves material, and there are multiple stretches where Close is kept offscreen for too long (and not just in the sense that "Glenn Close isn't onscreen right this second" is always kind of too long, for my tastes, with this performance). But its marriage of story beats with the beautifully constructed setting and the meticulous sonic framework of George Fenton's Classical-flavored score is always done very well, even when the story beats themselves are of less interest, and the film in general keeps a delicate balance between "all this hedonism is despicable" and "all this hedonism is delectable", from its quippy script through to its performances. For all that this looks like an overly-manicured prestige picture, and it has the Oscar and BAFTA nomination hauls to go along with it, Dangeous Liaisons is also just, like, a really good movie, putting a handsome gloss on sordid material in a way that might not quite feel "dangerous", but is at least extremely bracing.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Categories: costume dramas, love stories, oscarbait, satire, worthy adaptations