Summer of Blood: Back to Norman

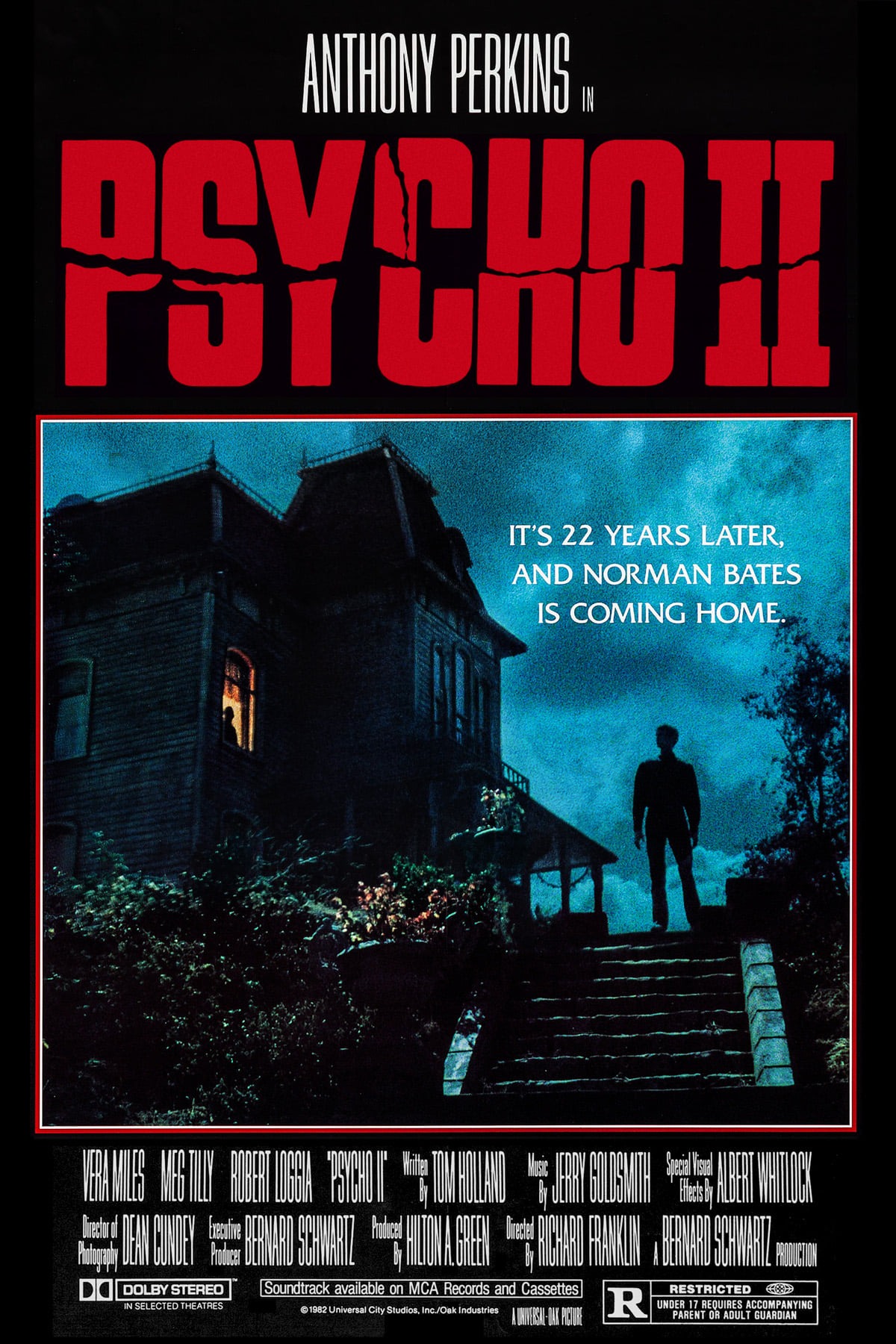

There probably aren't more than a half-dozen movies in the history of American cinema more sacrosanct than Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho from 1960, a film standing proudly alone as such a defining achievement in cinema that the mere notion of ever trying to cash in on it in any way is genuinely immoral. Which hasn't stood in the way of Psycho becoming a sprawling franchise, with three sequels, another sequel in a different continuity, a remake, and a prequel TV series, and so much for "sacrosanct" as a word that means a good god-damn to anybody in Hollywood when there's a buck to be made. But here's the twist (for you need a twist if you're talking about Psycho, yes?), and it's a happy one: although I would have responded to the news, in 1983, that Universal was making a Psycho II by earnestly entreating the government to extradite every single member of the production team to The Hague in order to be tried for crimes against humanity, it actually turns out to be the case that Psycho II is pretty good - far, far better than 23-years-later follow-up to Psycho had any right to be, on top of being far, far better than a slasher sequel had any right to be in 1983.

I am already begging the question. Is Psycho II a "slasher sequel"? Certainly, the existence of the slasher subgenre was a necessary prerequisite to its existence (as was, I suspect, Hitchcock's death in 1980 - I'm not sure that he had a legal right to prevent the existence of Psycho sequels, but I sure as hell can't imagine anybody having the cast-iron balls to try to make one without his blessing). But whether it counts as a "slasher film" is tricky to say. It has slasher-style deaths inside of a narrative that is nothing at all like a slasher movie; even with a final tally of six dead bodies, a 300% increase over the two victims in Psycho, I think it would be tough to call this a "body count movie" because of how they're distributed across to film (i.e. they aren't distributed "across" the film - most of them happen basically in one steady wave right at the end, as various characters' schemes and madness start go go of the rails). Outside of one shower scene, it offers very little to the meat-and-potatoes exploitation picture crowd, preferring to focus on a middle-aged man's unpromising attempts to keep himself together while the whole world is built around breaking him apart.

All of which points out another thing about Psycho Ii: it's a fair and not at all easy sequel to Psycho. It was conceived and written with a clear goal of trying to expand outwards from the situation where that film ended up, taking into account all the things that happened in it, and telling a story that feels like it's grappling with with the fallout from the first movie, and never just replicating it for cheap thrills. After 22 years in the custody of psychiatrists, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins, returning to the role that both made him a superstar and effectively ended his career, since it left him as badly typecast as any actor has been) has finally been declared of sound mind, having finally been disabused of the believe that his dead mother still lives and can take over his body. This horribly infuriates Lila Loomis (Vera Miles, also returning), sister of the dead Marion Crane, the penultimate victim of Norman's psychopathic behavior back in the '60s (Psycho II states, clear as a bell, that Norman was responsible for seven murders; my memory of the first film pretty confidently only gets us to four), but her fury isn't going to amount to anything: Norman is discharged and sent back to the small California town he came from, to restart live.

That get us to the one extravagant contrivance Psycho II needs to ask us to swallow in order to work: Norman is still the legal owner of the Bates Motel, which is presently being managed on his behalf by one Warren Toomey (Dennis Franz), and it seems like a good idea to everyone for Norman to just go straight back to the house where he lived with his dead mother's mummified corpse for many years. Even accepting the second part of that, it's already a lot to imagine that the state wouldn't have liquidated, like, all of his assets. But no matter, if the movie is going to be the movie, it needs to put Norman in the spooky old building that has already shattered his brain into tiny pieces once, so he can start reliving everything that happened there, and so begin to drive himself into a panic wondering if he might be heading right back into the homicidal madness he just got over.

That, in brief, is the whole of the film: Norman desperately wants to be healthy and not a psycho killer, and he's not sure that he has the fortitude to live up to that relatively simple dream. There's decoration around that: most importantly, Mary (Meg Tilly), his co-worker at a greasy spoon, ends up coming to live in his Gothic dump of a house, having been thrown out by her boyfriend, and letting Norman's desperate, panicky need to have anybody else in the building to keep him grounded overcome her visible nervousness at staying with him. But mostly, this is all about Norman, who has been made a far more sympathetic, relatable figure than he was in the 1960 film, mostly just by virtue of being front and center this time around. Perkins is giving an extremely good performance here, revisiting the timorous delicacy of the character the first time around, but amplifying it: 1960 Norman was scattered and nervous and fragile, but there was a slight youthful cockiness beneath it, a sharpness of tone and expression that flared up every now and then, but 1983 Norman is middle-aged and has the defeated fatigue of middle age to come with it. It's hard not to read Perkins' own dismal 23 years into the new performance: not only had his career gone completely off-track, he'd spent a sizable portion of the '70s deciding that the source of all his personal unhappiness was that he was gay, and diving with religious zeal into conversion therapy in an attempt to force himself to like women. It's hard not to see the new Norman, with his plaintively gaunt expressions of feeble hope the anguish that consumes his whole frame when he thinks he's hallucinating Mother again, and feel like we're seeing Perkins's own miseries fluttering across the screen like a broken-winged butterfly. Horribly tragic for the actor, no two ways about it, but it does a lot for Psycho II to have Norman turned into such a pitiable soul, anxious to take control of his own brain and unable to actually do so.

It helps a lot that the film's screenplay, written by Tom Holland, manages to be so persuasively ambiguous over what the hell is going on. We know this much: somebody is dressing up like a skinny old woman and murdering people with a knife in and around the Bates Motel. But the film largely does a good job of keeping its options open as to who that might be. Eventually, when it explains what's going on, it does so in the form of a just incredibly shitty twist, though to its credit, the twist for sure gives Perkins some big notes to play. They're unsatisfying notes, but they're big. But for the bulk of the film, Psycho II focuses mostly on the ambiguity, giving us more information that Norman gets, but not about anything that would actually let us answer the question of who is dressing up as Mother.

It is, in other words, a character drama that has put on the clothes of a slasher film so it can be marketed and sold, and mostly a very good character drama. Perkins is great, Tilly is great, and they're great together, even though he apparently hated her on set. Not all of the material around them is great: I appreciated Miles's gusto in going for the she goes for, but it feels like the film has to character assassinate Lila a bit to tell the story it wants. And that does bring us to the question I've been sort of not looking at too directly: so, how is it as a sequel to Psycho? Is it literally possible for a film to exist that answers that question as "pretty great"? At the very least, it's not a lazy retread. The film was directed by Richard Franklin, who very obviously got the job because of Roadgames, a 1981 Australian thriller that was all but officially a remake of Hitchcock's Rear Window, which made him probably best choice to make a Hitchcock sequel of any filmmaker after Brian De Palma, who said no when they asked him. And Franklin is up to difficult game: he's copying the original, riffing on it, and very pointedly going in different directions, all on a scene by scene basis. So, for example, there's a kill scene that copies, exactly, one of the editing tricks from the shower scene in the original movie. For that matter, we see the actual shower scene, played not quite in full right at the start of this movie, in the most blatantly artless, cynical decision the film ever makes. And a ruinous one, because if there's one thing that's going to make your movie look stale and inept, it would be giving the viewer nice fresh memories of a sequence that undoubtedly still seemed bold and transgressive in 1983, because it still seemed that way in 2022.

But I distracted myself. One murder copies the shower scene; but it's not in a shower. There's a shower scene, but it's not a murder. The weird and discombobulating "look straight down from ninety degrees" angle that Hitchcock used to frame his film's second killing keeps showing up in scenes that have nothing to do with death. The "eye illuminated by a peephole" shot is replicated but the implications of voyeurism aren't. So Psycho II is very eagerly reminding us of Psycho, but never replicating its effects. Meanwhile, Franklin is trotting out a bunch of new tricks that have nothing at all to do with the original: canted angles to mark out the places where Norman is feeling particularly unsteady about what's real and what isn't; repeatedly showing us knives entering skin, something that the original movie famously and specifically does not do. He tends to block scenes "backwards": Norman is on the opposite side of the screen than he was in the 1960 film in a scene discussing a light sandwich-based dinner.

Franklin isn't the only one who's doing this, either. The film's score was by Jerry Goldsmith, taking on the extraordinary task of writing the music for a sequel to a movie with one of the all-time legendary scores, and on top of it, he had been mentored for a time by Bernard Herrmann. What he came up with is far from his best work, but it's conceptually fascinating, replacing Herrmann's strings-only orchestrations with a full orchestra in which the strings are specifically never prominent, keeping Herrmann's rhythms while avoiding any of his melodies. It's basically the mirror of the Psycho score, a little bit like how the blocking mirrors the original.

All of this, especially as anchored around Perkins's pointedly "the same thing only even more so" performance gives Psycho II a very gratifying mixture of familiarity and freshness, competently gesturing towards Psycho without using it as a crutch. This cuts both ways: it's hard to shake the feeling that it's finding clever, unexpected ways to answer questions that fundamentally had no business whatsover getting asked, and its commitment to following the implicit logic of the Psycho lore gets tangled up with the inconvenient fact that "Psycho lore" had no reason to exist prior to this film's creation. And yet, this is so much closer to the best-case-imaginable version of this concept that I have to admire it. It's tasteful, classic, and psychologiclally sensitive despite being a tacky cash-in, and an attempt to keep the slasher boom going all the way in 1983. It should be repulsive doggerel, and instead it's one of the only films of its era to actually care (and care intensely) about trying to feel its way into the fractured mind of a dangerous killer, as a pathetic human rather than as a savage monster. It's pretty remarkable, and frankly it's downright unreasonable for it to be this successful at the terribly misguided games it's playing.

Body Count: 6, as mentioned, not counting Marion's death in the opening footage taken from the 1960 film, nor counting the death of Norman's mother, which we hear but do not see in flashback.

Reviews in this series

Psycho (Hitchcock, 1960)

Psycho II (Franklin, 1983)

Psycho III (Perkins, 1986)

Psycho IV: The Beginning (Garris, 1990)

Psycho (Van Sant, 1998)

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

I am already begging the question. Is Psycho II a "slasher sequel"? Certainly, the existence of the slasher subgenre was a necessary prerequisite to its existence (as was, I suspect, Hitchcock's death in 1980 - I'm not sure that he had a legal right to prevent the existence of Psycho sequels, but I sure as hell can't imagine anybody having the cast-iron balls to try to make one without his blessing). But whether it counts as a "slasher film" is tricky to say. It has slasher-style deaths inside of a narrative that is nothing at all like a slasher movie; even with a final tally of six dead bodies, a 300% increase over the two victims in Psycho, I think it would be tough to call this a "body count movie" because of how they're distributed across to film (i.e. they aren't distributed "across" the film - most of them happen basically in one steady wave right at the end, as various characters' schemes and madness start go go of the rails). Outside of one shower scene, it offers very little to the meat-and-potatoes exploitation picture crowd, preferring to focus on a middle-aged man's unpromising attempts to keep himself together while the whole world is built around breaking him apart.

All of which points out another thing about Psycho Ii: it's a fair and not at all easy sequel to Psycho. It was conceived and written with a clear goal of trying to expand outwards from the situation where that film ended up, taking into account all the things that happened in it, and telling a story that feels like it's grappling with with the fallout from the first movie, and never just replicating it for cheap thrills. After 22 years in the custody of psychiatrists, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins, returning to the role that both made him a superstar and effectively ended his career, since it left him as badly typecast as any actor has been) has finally been declared of sound mind, having finally been disabused of the believe that his dead mother still lives and can take over his body. This horribly infuriates Lila Loomis (Vera Miles, also returning), sister of the dead Marion Crane, the penultimate victim of Norman's psychopathic behavior back in the '60s (Psycho II states, clear as a bell, that Norman was responsible for seven murders; my memory of the first film pretty confidently only gets us to four), but her fury isn't going to amount to anything: Norman is discharged and sent back to the small California town he came from, to restart live.

That get us to the one extravagant contrivance Psycho II needs to ask us to swallow in order to work: Norman is still the legal owner of the Bates Motel, which is presently being managed on his behalf by one Warren Toomey (Dennis Franz), and it seems like a good idea to everyone for Norman to just go straight back to the house where he lived with his dead mother's mummified corpse for many years. Even accepting the second part of that, it's already a lot to imagine that the state wouldn't have liquidated, like, all of his assets. But no matter, if the movie is going to be the movie, it needs to put Norman in the spooky old building that has already shattered his brain into tiny pieces once, so he can start reliving everything that happened there, and so begin to drive himself into a panic wondering if he might be heading right back into the homicidal madness he just got over.

That, in brief, is the whole of the film: Norman desperately wants to be healthy and not a psycho killer, and he's not sure that he has the fortitude to live up to that relatively simple dream. There's decoration around that: most importantly, Mary (Meg Tilly), his co-worker at a greasy spoon, ends up coming to live in his Gothic dump of a house, having been thrown out by her boyfriend, and letting Norman's desperate, panicky need to have anybody else in the building to keep him grounded overcome her visible nervousness at staying with him. But mostly, this is all about Norman, who has been made a far more sympathetic, relatable figure than he was in the 1960 film, mostly just by virtue of being front and center this time around. Perkins is giving an extremely good performance here, revisiting the timorous delicacy of the character the first time around, but amplifying it: 1960 Norman was scattered and nervous and fragile, but there was a slight youthful cockiness beneath it, a sharpness of tone and expression that flared up every now and then, but 1983 Norman is middle-aged and has the defeated fatigue of middle age to come with it. It's hard not to read Perkins' own dismal 23 years into the new performance: not only had his career gone completely off-track, he'd spent a sizable portion of the '70s deciding that the source of all his personal unhappiness was that he was gay, and diving with religious zeal into conversion therapy in an attempt to force himself to like women. It's hard not to see the new Norman, with his plaintively gaunt expressions of feeble hope the anguish that consumes his whole frame when he thinks he's hallucinating Mother again, and feel like we're seeing Perkins's own miseries fluttering across the screen like a broken-winged butterfly. Horribly tragic for the actor, no two ways about it, but it does a lot for Psycho II to have Norman turned into such a pitiable soul, anxious to take control of his own brain and unable to actually do so.

It helps a lot that the film's screenplay, written by Tom Holland, manages to be so persuasively ambiguous over what the hell is going on. We know this much: somebody is dressing up like a skinny old woman and murdering people with a knife in and around the Bates Motel. But the film largely does a good job of keeping its options open as to who that might be. Eventually, when it explains what's going on, it does so in the form of a just incredibly shitty twist, though to its credit, the twist for sure gives Perkins some big notes to play. They're unsatisfying notes, but they're big. But for the bulk of the film, Psycho II focuses mostly on the ambiguity, giving us more information that Norman gets, but not about anything that would actually let us answer the question of who is dressing up as Mother.

It is, in other words, a character drama that has put on the clothes of a slasher film so it can be marketed and sold, and mostly a very good character drama. Perkins is great, Tilly is great, and they're great together, even though he apparently hated her on set. Not all of the material around them is great: I appreciated Miles's gusto in going for the she goes for, but it feels like the film has to character assassinate Lila a bit to tell the story it wants. And that does bring us to the question I've been sort of not looking at too directly: so, how is it as a sequel to Psycho? Is it literally possible for a film to exist that answers that question as "pretty great"? At the very least, it's not a lazy retread. The film was directed by Richard Franklin, who very obviously got the job because of Roadgames, a 1981 Australian thriller that was all but officially a remake of Hitchcock's Rear Window, which made him probably best choice to make a Hitchcock sequel of any filmmaker after Brian De Palma, who said no when they asked him. And Franklin is up to difficult game: he's copying the original, riffing on it, and very pointedly going in different directions, all on a scene by scene basis. So, for example, there's a kill scene that copies, exactly, one of the editing tricks from the shower scene in the original movie. For that matter, we see the actual shower scene, played not quite in full right at the start of this movie, in the most blatantly artless, cynical decision the film ever makes. And a ruinous one, because if there's one thing that's going to make your movie look stale and inept, it would be giving the viewer nice fresh memories of a sequence that undoubtedly still seemed bold and transgressive in 1983, because it still seemed that way in 2022.

But I distracted myself. One murder copies the shower scene; but it's not in a shower. There's a shower scene, but it's not a murder. The weird and discombobulating "look straight down from ninety degrees" angle that Hitchcock used to frame his film's second killing keeps showing up in scenes that have nothing to do with death. The "eye illuminated by a peephole" shot is replicated but the implications of voyeurism aren't. So Psycho II is very eagerly reminding us of Psycho, but never replicating its effects. Meanwhile, Franklin is trotting out a bunch of new tricks that have nothing at all to do with the original: canted angles to mark out the places where Norman is feeling particularly unsteady about what's real and what isn't; repeatedly showing us knives entering skin, something that the original movie famously and specifically does not do. He tends to block scenes "backwards": Norman is on the opposite side of the screen than he was in the 1960 film in a scene discussing a light sandwich-based dinner.

Franklin isn't the only one who's doing this, either. The film's score was by Jerry Goldsmith, taking on the extraordinary task of writing the music for a sequel to a movie with one of the all-time legendary scores, and on top of it, he had been mentored for a time by Bernard Herrmann. What he came up with is far from his best work, but it's conceptually fascinating, replacing Herrmann's strings-only orchestrations with a full orchestra in which the strings are specifically never prominent, keeping Herrmann's rhythms while avoiding any of his melodies. It's basically the mirror of the Psycho score, a little bit like how the blocking mirrors the original.

All of this, especially as anchored around Perkins's pointedly "the same thing only even more so" performance gives Psycho II a very gratifying mixture of familiarity and freshness, competently gesturing towards Psycho without using it as a crutch. This cuts both ways: it's hard to shake the feeling that it's finding clever, unexpected ways to answer questions that fundamentally had no business whatsover getting asked, and its commitment to following the implicit logic of the Psycho lore gets tangled up with the inconvenient fact that "Psycho lore" had no reason to exist prior to this film's creation. And yet, this is so much closer to the best-case-imaginable version of this concept that I have to admire it. It's tasteful, classic, and psychologiclally sensitive despite being a tacky cash-in, and an attempt to keep the slasher boom going all the way in 1983. It should be repulsive doggerel, and instead it's one of the only films of its era to actually care (and care intensely) about trying to feel its way into the fractured mind of a dangerous killer, as a pathetic human rather than as a savage monster. It's pretty remarkable, and frankly it's downright unreasonable for it to be this successful at the terribly misguided games it's playing.

Body Count: 6, as mentioned, not counting Marion's death in the opening footage taken from the 1960 film, nor counting the death of Norman's mother, which we hear but do not see in flashback.

Reviews in this series

Psycho (Hitchcock, 1960)

Psycho II (Franklin, 1983)

Psycho III (Perkins, 1986)

Psycho IV: The Beginning (Garris, 1990)

Psycho (Van Sant, 1998)

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Categories: mysteries, needless sequels, slashers, summer of blood, thrillers, worthy sequels