Your lion eyes

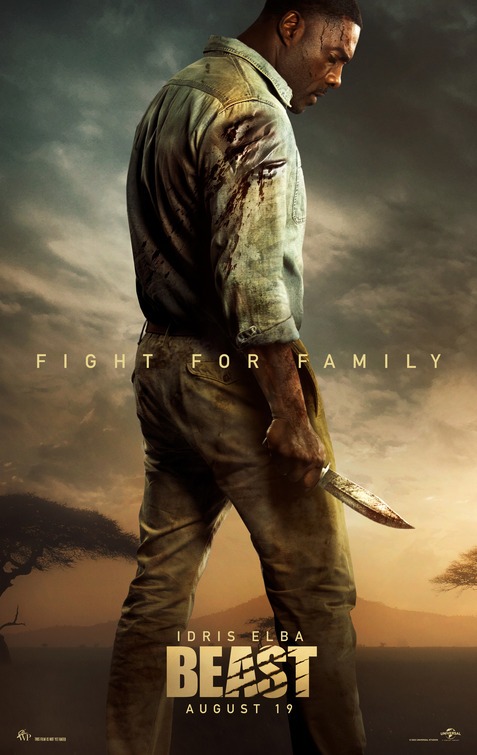

It would be accurate to describe Beast as "the movie where Idris Elba kicks a CGI lion in the face". But it would be even more accurate to describe Beast as "the movie where Idris Elba kicks a CGI lion in the face twice", which of course means it is twice as good. And as far as that goes, this is basically as good as I can possibly imagine "the movie where Idris Elba kicks a CGI lion in the face twice" being. I can, to be sure, imagine tweaks to Beast that would have made me happier; "the movie where Idris Elba kicks an animatronic lion in the face twice", for example. But it's 2022 and I'm not greedy enough to allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good in this matter.

The film, all of 93 minutes long, gets us to the point pretty quickly: Dr. Nate Samuels (Elba) has taken his two daughters, Meredith or "Mer" (Iyana Halley) and Norah (Leah Jeffries) to South Africa, in the region of that country where their late mother was born and grew up. This is, we figure out in no time, an apology trip: Nate and his wife had been separated at the time of her death from cancer, and Mer, at least, is happy to tell him to his face that his absence in her declining months has led to a rift between father and daughter that's not getting patched soon, or ever. Why, just about the only thing that might cause Mer to soften towards Nate is if they get trapped together in an SUV by a huge, erratically hostile lion, and he repeatedly risks his life to protect the girls, and later risks his life even more to carry Mer to a location where he can perform emergency field surgery to protect her from the grievous wounds that she has incurred from the selfsame lion.

That's nearly all of the content of Beast, though I have, in my quest to be pithy, overlooked the fourth character of significance, Martin Battles (Sharlto Copley), a friend of Mom's from way back, who introduced her and Nate in the first place. The first act of the film largely consists of the three Americans (it's not explained precisely how the girls ended up with that accent if their dad is Idris Elba and their mom was from South Africa, but whatever, it's a movie) arriving at Martin's remote house on the edge of a wildlife preserve, where most of that exposition gets blasted out on the sides of scenes that are largely doing other things to set up the plot, and three cheers to screenwriter Ryan Engle for racing through all that material so quickly and cleanly. Their first morning, he then drives them out on a private tour of the parts of the reserve that are closed to the public, stopping for a visit with a lackadaisical pride of lions so we can get some heavy foreshadowing, and eventually arriving at a small village that is suspiciously empty of people, though as Nate and Martin start poking around, they find that at least some of those people have stayed behind, in the form of horribly mangled people. Martin directly shifts into "official park warden" mode and drives them at top speed towards a station to report what he's seen, but along they way they stop to rescue one of the villagers, covered in blood and clearly not long for this world, and it's while they're stopped that they get a most unwelcome visitor in the form of an enormous and foul-tempered male lion, the soul survivor of a poaching ambush the previous night that killed his entire harem, as we saw in the film's opening scene. So really, he's just out for revenge, though he's not being especially judicious in who he decides to attack.

That takes barely more time to play out than it took me to write it, and once the lion shows up, Beast transforms into a drum-tight survival thriller as the three main characters spend a huge number of those 93 minutes either inside, atop, or beneath Martin's SUV, trying to come up with ways to evade the lion, and maybe put a few tranquilizer darts into its hard (Martin spends most of this part of the film stuck on a small muddy outcropping in a pond a few minutes' walk into the brush, bleeding out from his own unsuccessful first meeting with the lion). It's not quite a single-location thriller - the first and third acts take place in entirely different locations, and there are three main "spots" even in the middle sequence - but the appeal of Beast is very much the appeal of such movies, as part of the oppressive tension generated comes from the sense of being stuck in a car that feels a bit less secure every time the lion rams it at top speed.

In that respect, the film benefits mightily from the mildly show-offy directing of Baltasar Kormákur, an Icelandic director who has mostly been making junky garbage since he came to the U.S. film industry, and has been failing over and over again to make an American film on par with his terrific 2012 survival thriller The Deep. Beast doesn't get us there, but it comes closer than anything else he's done (I say this even while being a larger-than-average fan of his last film, 2018's Adrift), and a huge part of the reason why is a trick he uses that really, really felt like a hacky gimmick in the early going. Most of the scenes in Beast take place across sinuous tracking shots that last for very long portions of the scenes, gliding around and flipping back and forth to take in all the spaces we visit. When it's Nate and his daughters visiting Martin's house, this feels like a tedious bit of needlessly "hip" digital style, as Kormákur and cinematographer Philippe Rousselot demonstrate that they sure know how to use lightweight cameras in an indiscriminate way. Once the lion shows up, though, the motive behind the aesthetic suddenly becomes terribly clear: it is a great way to give a huge shot of adrenaline to the tension, as the camera spins about tensely, trying to look every possible way to see where the hell the lion might be coming from next, and making it painfully, dreadfully clear that what we can see is a fairly insubstantial of what we can't. It makes for some of the tensest suspense cinema in a long while, a real-time nightmare of limited perspective and uncertainty.

This isn't the only card Beast has up its sleeve. It also has an actually pretty good lion; not one that you'd ever mistake for the real thing, but it's kept in movement enough that it's possible to play along. And part of the reason it's very clear that the big cat is a visual effect is that it has been given blatantly unrealistic facial expressions, angry snarls that convey the wrath of a cunning predator with hot-blooded revenge on its mind. It's a mean animal, and as hokey as it is, I kind of really loved how palpable that meanness was. It's a damn sight better than the all-CGI cats in the 2019 The Lion King, anyways.

Another thing that gives the film a considerable leg up is that Nate, Mer, and Norah are such interestingly-defined figures; not that they are interesting, since the facts of their lives and their recent trauma is such boilerplate. But the way the script and the actors build the characters out is kind of weird and offbeat, and extremely gratifying. Their three-way relationship is expressed in a shaggy sort of naturalism, where what makes them feel real and organic isn't so much what the characters say as how they do it, between Nate's difficulty remaining focused, Mer's readiness to pick fights (Halley does exemplary work playing the kind of person who has a knack for saying extremely cutting, meanspirited things and then immediately regretting that she did so, but doubling-down on it anyway because to do otherwise would be to admit that she made a mistake; she's one of the most teenaged teenagers I've seen in a movie in a good while, in that respect), and Norah's habit of immediately falling into referee mode, not because she hates the fights, but because she's been doing this for so long it happens without planning. Once that exact dynamic gets transferred to the lion attack scenes, it becomes exciting and prickly and tremendously human, making these people feel more like people and less like the generic types who tend to find themselves in the midst of wild animal attacks in the movies.

This is all terribly satisying stuff, impeccably well-made cinematic junk food; this does not mean it transcends being junk food, not at all. Beast is extremely ridiculous in ways that are very tough to overlook, mostly in that the film decides that Nate, an urban medical doctor from the United States, is approximately evenly-matched with a very large and irrationally cruel lion. I don't make it as far in fights with my housecats as Nate does with an enormous, hyper-violent predator. That's all part of the fun, of course, but it's one thing to know intellectually that movie heroes would die in real life, and to see Elba kick the CGI lion twice, both times without immediately losing everything below the knee, or to see him outrun the lion (at the very least, he keeps pace with it), or to watch a climactic fight where he manages to wrestle with it, unaided, for a good 45 seconds. That last one was the part I could not keep my suspension of disbelief alive any longer, for the record. This kind of thing can all be implied without us actually seeing it right there onscreen, and the more fights Nate survives, the harder it is to take the tension seriously, since obviously this man is impervious to physical damage. But that's more the film overplaying its hand than seriously compromising itself; even at its goofiest (and it's all pretty much goofy), Beast is a delightful summertime killer animal flick, and one of the most gratifyingly unfussy, trimmed-down, "just wants to be good at this one thing" wide-release American movies since the last delightful summertime killer animal flick, Crawl in 2019. Damn good company to be in, and Beast fully earns that comparison.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

The film, all of 93 minutes long, gets us to the point pretty quickly: Dr. Nate Samuels (Elba) has taken his two daughters, Meredith or "Mer" (Iyana Halley) and Norah (Leah Jeffries) to South Africa, in the region of that country where their late mother was born and grew up. This is, we figure out in no time, an apology trip: Nate and his wife had been separated at the time of her death from cancer, and Mer, at least, is happy to tell him to his face that his absence in her declining months has led to a rift between father and daughter that's not getting patched soon, or ever. Why, just about the only thing that might cause Mer to soften towards Nate is if they get trapped together in an SUV by a huge, erratically hostile lion, and he repeatedly risks his life to protect the girls, and later risks his life even more to carry Mer to a location where he can perform emergency field surgery to protect her from the grievous wounds that she has incurred from the selfsame lion.

That's nearly all of the content of Beast, though I have, in my quest to be pithy, overlooked the fourth character of significance, Martin Battles (Sharlto Copley), a friend of Mom's from way back, who introduced her and Nate in the first place. The first act of the film largely consists of the three Americans (it's not explained precisely how the girls ended up with that accent if their dad is Idris Elba and their mom was from South Africa, but whatever, it's a movie) arriving at Martin's remote house on the edge of a wildlife preserve, where most of that exposition gets blasted out on the sides of scenes that are largely doing other things to set up the plot, and three cheers to screenwriter Ryan Engle for racing through all that material so quickly and cleanly. Their first morning, he then drives them out on a private tour of the parts of the reserve that are closed to the public, stopping for a visit with a lackadaisical pride of lions so we can get some heavy foreshadowing, and eventually arriving at a small village that is suspiciously empty of people, though as Nate and Martin start poking around, they find that at least some of those people have stayed behind, in the form of horribly mangled people. Martin directly shifts into "official park warden" mode and drives them at top speed towards a station to report what he's seen, but along they way they stop to rescue one of the villagers, covered in blood and clearly not long for this world, and it's while they're stopped that they get a most unwelcome visitor in the form of an enormous and foul-tempered male lion, the soul survivor of a poaching ambush the previous night that killed his entire harem, as we saw in the film's opening scene. So really, he's just out for revenge, though he's not being especially judicious in who he decides to attack.

That takes barely more time to play out than it took me to write it, and once the lion shows up, Beast transforms into a drum-tight survival thriller as the three main characters spend a huge number of those 93 minutes either inside, atop, or beneath Martin's SUV, trying to come up with ways to evade the lion, and maybe put a few tranquilizer darts into its hard (Martin spends most of this part of the film stuck on a small muddy outcropping in a pond a few minutes' walk into the brush, bleeding out from his own unsuccessful first meeting with the lion). It's not quite a single-location thriller - the first and third acts take place in entirely different locations, and there are three main "spots" even in the middle sequence - but the appeal of Beast is very much the appeal of such movies, as part of the oppressive tension generated comes from the sense of being stuck in a car that feels a bit less secure every time the lion rams it at top speed.

In that respect, the film benefits mightily from the mildly show-offy directing of Baltasar Kormákur, an Icelandic director who has mostly been making junky garbage since he came to the U.S. film industry, and has been failing over and over again to make an American film on par with his terrific 2012 survival thriller The Deep. Beast doesn't get us there, but it comes closer than anything else he's done (I say this even while being a larger-than-average fan of his last film, 2018's Adrift), and a huge part of the reason why is a trick he uses that really, really felt like a hacky gimmick in the early going. Most of the scenes in Beast take place across sinuous tracking shots that last for very long portions of the scenes, gliding around and flipping back and forth to take in all the spaces we visit. When it's Nate and his daughters visiting Martin's house, this feels like a tedious bit of needlessly "hip" digital style, as Kormákur and cinematographer Philippe Rousselot demonstrate that they sure know how to use lightweight cameras in an indiscriminate way. Once the lion shows up, though, the motive behind the aesthetic suddenly becomes terribly clear: it is a great way to give a huge shot of adrenaline to the tension, as the camera spins about tensely, trying to look every possible way to see where the hell the lion might be coming from next, and making it painfully, dreadfully clear that what we can see is a fairly insubstantial of what we can't. It makes for some of the tensest suspense cinema in a long while, a real-time nightmare of limited perspective and uncertainty.

This isn't the only card Beast has up its sleeve. It also has an actually pretty good lion; not one that you'd ever mistake for the real thing, but it's kept in movement enough that it's possible to play along. And part of the reason it's very clear that the big cat is a visual effect is that it has been given blatantly unrealistic facial expressions, angry snarls that convey the wrath of a cunning predator with hot-blooded revenge on its mind. It's a mean animal, and as hokey as it is, I kind of really loved how palpable that meanness was. It's a damn sight better than the all-CGI cats in the 2019 The Lion King, anyways.

Another thing that gives the film a considerable leg up is that Nate, Mer, and Norah are such interestingly-defined figures; not that they are interesting, since the facts of their lives and their recent trauma is such boilerplate. But the way the script and the actors build the characters out is kind of weird and offbeat, and extremely gratifying. Their three-way relationship is expressed in a shaggy sort of naturalism, where what makes them feel real and organic isn't so much what the characters say as how they do it, between Nate's difficulty remaining focused, Mer's readiness to pick fights (Halley does exemplary work playing the kind of person who has a knack for saying extremely cutting, meanspirited things and then immediately regretting that she did so, but doubling-down on it anyway because to do otherwise would be to admit that she made a mistake; she's one of the most teenaged teenagers I've seen in a movie in a good while, in that respect), and Norah's habit of immediately falling into referee mode, not because she hates the fights, but because she's been doing this for so long it happens without planning. Once that exact dynamic gets transferred to the lion attack scenes, it becomes exciting and prickly and tremendously human, making these people feel more like people and less like the generic types who tend to find themselves in the midst of wild animal attacks in the movies.

This is all terribly satisying stuff, impeccably well-made cinematic junk food; this does not mean it transcends being junk food, not at all. Beast is extremely ridiculous in ways that are very tough to overlook, mostly in that the film decides that Nate, an urban medical doctor from the United States, is approximately evenly-matched with a very large and irrationally cruel lion. I don't make it as far in fights with my housecats as Nate does with an enormous, hyper-violent predator. That's all part of the fun, of course, but it's one thing to know intellectually that movie heroes would die in real life, and to see Elba kick the CGI lion twice, both times without immediately losing everything below the knee, or to see him outrun the lion (at the very least, he keeps pace with it), or to watch a climactic fight where he manages to wrestle with it, unaided, for a good 45 seconds. That last one was the part I could not keep my suspension of disbelief alive any longer, for the record. This kind of thing can all be implied without us actually seeing it right there onscreen, and the more fights Nate survives, the harder it is to take the tension seriously, since obviously this man is impervious to physical damage. But that's more the film overplaying its hand than seriously compromising itself; even at its goofiest (and it's all pretty much goofy), Beast is a delightful summertime killer animal flick, and one of the most gratifyingly unfussy, trimmed-down, "just wants to be good at this one thing" wide-release American movies since the last delightful summertime killer animal flick, Crawl in 2019. Damn good company to be in, and Beast fully earns that comparison.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Categories: action, summer movies, thrillers