Water, water every where

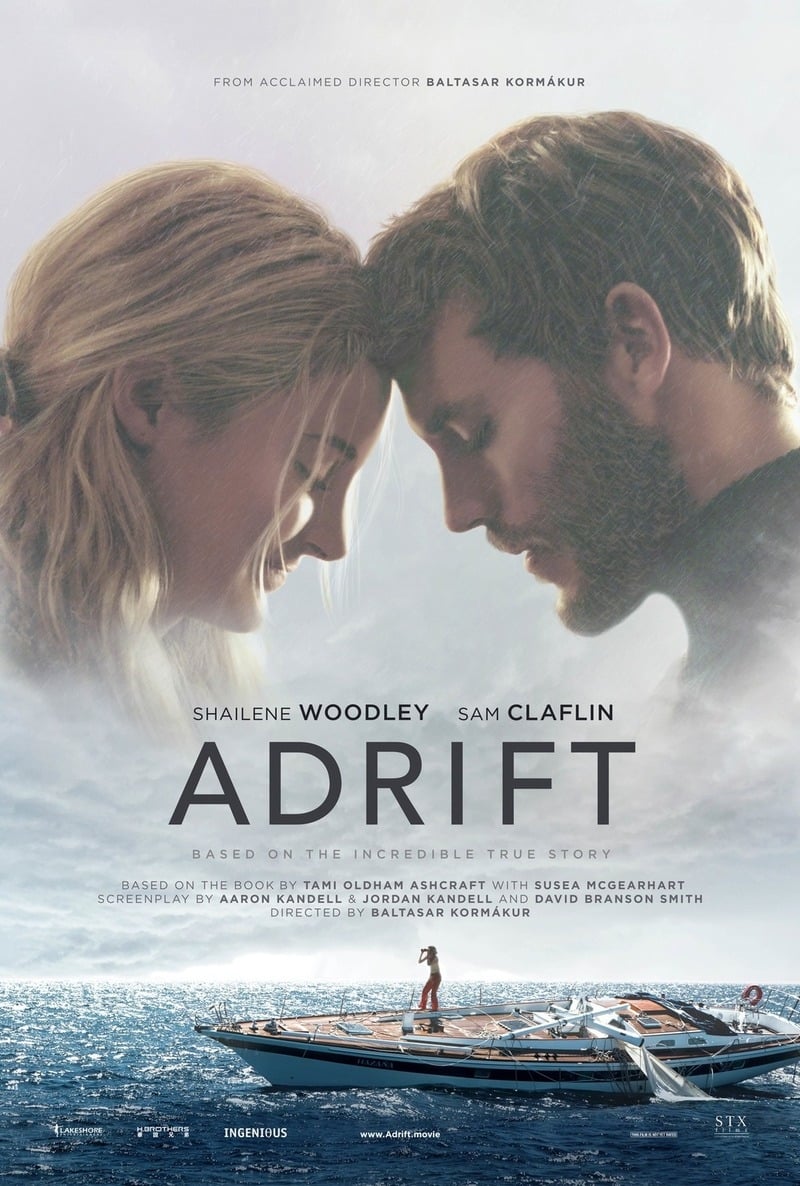

Adrift is a curious, inexplicable little beast. It starts out looking like one film and it ends up looking like a slightly but very importantly, different film, and neither of these look exactly like the film it was marketed as being. It's kind of too bad, because the film it ends up being is pretty strong for what it is (a quickie popcorn thriller with an on-the-rocks quasi-star and a killer plot hook), and would have been even stronger if the film's over desire to be clever and surprising hadn't gotten in the way of the story.

Not that there is much story. The film is taken from life: in 1983, 23-year-old Tami Oldham (Shailene Woodley) and 33-year-old Richard Sharp (Sam Claflin) met in Tahiti, where they both ended up during their respective "aimless wandering around the globe, doing nothing in particular while loving their irresponsible freedom" phases, and they fell in love. When Richard was given a healthy payday for sailing a yacht to San Diego, he asked Tami to come with him as his fiancé. All went well until they crossed the path of Hurricane Raymond, with exactly the results you'd expect from a two-person sailing yet getting caught up in a hurricane.

Adrift doesn't frontload that part; honestly, if the storm hadn't been front and center in the marketing campaign, I'd almost suggest that bringing it up was a spoiler. Instead, the film opens in the aftermath of a very nasty something, with Tami bolting awake, alone, on the ruined boat. For the next 96 minutes, the plot switches back and forth from Tami's frantic attempts to stay alive, find Richard floating on the upturned dinghy that used to be attached to the yacht, and figure out a way to navigate to the nearest land in the wide open Pacific, over to the couple's meeting and early flirtation on Tahiti, followed by their romantic journey off across the ocean to San Diego, where they fall even deeper in love. This other half of the movie builds up to that moment where Tami and Richard meet their fate, though it doesn't really lean on it. I don't suppose that it has to; the constant shuttling back to the desperate situation after the storm, where Richard has been laid up by a badly broken leg and cracked ribs, and both characters grow more caked with salty grime and sunburned flesh as the story grinds on brings in all the ominous fatalism that one summer B-picture can really claim to need.

On first glance, this two-pronged structure feels all wrong, but as Adrift floated on, it started to grow on me a great deal. There is, for one thing, the small perversity of how it's both a parallel and a mirror structure, which will involve the very mildest of MILD SPOILERS (but come on, it's not like this is going to end with two corpses dried up in a boat in the Pacific; we know just from the opening credits that Tami Oldham survived to write the memoir upon which the film is based): we have here a flashback plotline that jumps through several days and weeks of pastoral happiness and young people romance before suddenly everything goes bad, running exactly in tandem with a present-tense plotline that jumps in a similar way through several days and weeks of increasing misery and suffering before suddenly everything ends well. The result is a genuinely interesting and unexpected way of using the ol' "all plotlines climax at the same time" device that is, basically, the only reason for doing cross-cutting, since the climaxes reverse each other. I think one could go too far in praising screenwriters Aaron Kandell, Jordan Kandell, and David Branson Smith in finding this elegant, tightly-pieced approach, but it is tight, and elegant too. It's an admirable little piece of storytelling, far beyond the basic requirements of a summertime survival thriller.

The other thing the structure does is to quietly push our attention away from what it looks like the movie is doing - All Is Lost with a woman and an almost totally useless Sam Claflin* - towards what it is actually doing, which is less the "what" of surviving on a boat lost in the Pacific, than the "how". We understand from the Tahiti scenes, and from Woodley's generally determined, square-jawed performance (it is, by some distance, the most I've ever liked her in a movie) that Tami is plucky and resourceful, and to a certain degree, that gets us where we need to be; but there's "resourceful" and there's having the bottomless self-reliance and untapped strength to survive for six weeks in the absolute middle of nowhere with meager resources. Adrift is really, secretly the story of what Tami has to do within herself to keep going, and the flashbacks, which are always subjectively cued but generally not in ways that make a big deal about it, are really there to show us what she's drawing on.

All of that would be enough to catch my attention: in the increasingly crowded "isolationist survival" genre, having some interesting layers of psychology is enough to put Adrift a notch above many of its peers. I would expect nothing less from Baltasar Kormákur, an Icelandic director whose English-language films have all been a touch wheezy and rickety, but whose 2012 film The Deep is one of the best survivalist films of the 2010s, and not for dissimilar reasons: it's about emotional fortitude rather than pure physical endurance, and this is perhaps the difference between a movie and something less-than.

That being said, Adrift has one more card to play: it is immodestly well-made. The film boasts some stupidly good camerawork, courtesy of the great Robert Richardson; he and Kormákur have hit upon the world's most obvious way to suggest floating, which does not mean that it's ineffective, which is to indulge in many longish tracking shots, gliding and bobbing along in an apparent abandonment of the physics of the space they inhabit. Any film shot in a boat on water has to deal with the great conflict between keeping the horizon line steady or keeping the actors in front of that horizon steady; Adrift deals with this by introducing a third level of rocking movement, so that the camera does not seem to be rocking with the boat nor holding steady, but rocking with some other source entirely. It sounds like it should be repulsively nauseating, but it ends up being the most natural thing in the world, giving a hugely natural, environmental character to the camera that contributes to our sense of the ocean's overwhelming presence even in the shots on dry land. Hell, Richardson even manages to make that hoary old "the camera is one-quarter submerged, so occasionally it drops below the water level and we see the characters' legs, and then it bobs back up" trick that's as old as in-water cinematography do useful, interesting things. Add to that the film's excellent sound mix, which evokes the flat echoing quality of sounds in a huge empty space, as well as the constant little thuds and thwacks that happen as water smacks into a boat, wave after wave, and you have a film that evokes the omnipresence of water when you're in a boat better than anything has in a good long while. The film is not without its problems - the biggest being some questionable decisions about when to withhold information from the audience and when to provide it, as well as Claflin being completely awful and sort of wrecking the romance that is meant to be the foundation of everything else - but it's very thoughtfully made and viscerally effective for what amounts to a trashy summertime potboiler.

*I understand that this phrase is redundant.

Not that there is much story. The film is taken from life: in 1983, 23-year-old Tami Oldham (Shailene Woodley) and 33-year-old Richard Sharp (Sam Claflin) met in Tahiti, where they both ended up during their respective "aimless wandering around the globe, doing nothing in particular while loving their irresponsible freedom" phases, and they fell in love. When Richard was given a healthy payday for sailing a yacht to San Diego, he asked Tami to come with him as his fiancé. All went well until they crossed the path of Hurricane Raymond, with exactly the results you'd expect from a two-person sailing yet getting caught up in a hurricane.

Adrift doesn't frontload that part; honestly, if the storm hadn't been front and center in the marketing campaign, I'd almost suggest that bringing it up was a spoiler. Instead, the film opens in the aftermath of a very nasty something, with Tami bolting awake, alone, on the ruined boat. For the next 96 minutes, the plot switches back and forth from Tami's frantic attempts to stay alive, find Richard floating on the upturned dinghy that used to be attached to the yacht, and figure out a way to navigate to the nearest land in the wide open Pacific, over to the couple's meeting and early flirtation on Tahiti, followed by their romantic journey off across the ocean to San Diego, where they fall even deeper in love. This other half of the movie builds up to that moment where Tami and Richard meet their fate, though it doesn't really lean on it. I don't suppose that it has to; the constant shuttling back to the desperate situation after the storm, where Richard has been laid up by a badly broken leg and cracked ribs, and both characters grow more caked with salty grime and sunburned flesh as the story grinds on brings in all the ominous fatalism that one summer B-picture can really claim to need.

On first glance, this two-pronged structure feels all wrong, but as Adrift floated on, it started to grow on me a great deal. There is, for one thing, the small perversity of how it's both a parallel and a mirror structure, which will involve the very mildest of MILD SPOILERS (but come on, it's not like this is going to end with two corpses dried up in a boat in the Pacific; we know just from the opening credits that Tami Oldham survived to write the memoir upon which the film is based): we have here a flashback plotline that jumps through several days and weeks of pastoral happiness and young people romance before suddenly everything goes bad, running exactly in tandem with a present-tense plotline that jumps in a similar way through several days and weeks of increasing misery and suffering before suddenly everything ends well. The result is a genuinely interesting and unexpected way of using the ol' "all plotlines climax at the same time" device that is, basically, the only reason for doing cross-cutting, since the climaxes reverse each other. I think one could go too far in praising screenwriters Aaron Kandell, Jordan Kandell, and David Branson Smith in finding this elegant, tightly-pieced approach, but it is tight, and elegant too. It's an admirable little piece of storytelling, far beyond the basic requirements of a summertime survival thriller.

The other thing the structure does is to quietly push our attention away from what it looks like the movie is doing - All Is Lost with a woman and an almost totally useless Sam Claflin* - towards what it is actually doing, which is less the "what" of surviving on a boat lost in the Pacific, than the "how". We understand from the Tahiti scenes, and from Woodley's generally determined, square-jawed performance (it is, by some distance, the most I've ever liked her in a movie) that Tami is plucky and resourceful, and to a certain degree, that gets us where we need to be; but there's "resourceful" and there's having the bottomless self-reliance and untapped strength to survive for six weeks in the absolute middle of nowhere with meager resources. Adrift is really, secretly the story of what Tami has to do within herself to keep going, and the flashbacks, which are always subjectively cued but generally not in ways that make a big deal about it, are really there to show us what she's drawing on.

All of that would be enough to catch my attention: in the increasingly crowded "isolationist survival" genre, having some interesting layers of psychology is enough to put Adrift a notch above many of its peers. I would expect nothing less from Baltasar Kormákur, an Icelandic director whose English-language films have all been a touch wheezy and rickety, but whose 2012 film The Deep is one of the best survivalist films of the 2010s, and not for dissimilar reasons: it's about emotional fortitude rather than pure physical endurance, and this is perhaps the difference between a movie and something less-than.

That being said, Adrift has one more card to play: it is immodestly well-made. The film boasts some stupidly good camerawork, courtesy of the great Robert Richardson; he and Kormákur have hit upon the world's most obvious way to suggest floating, which does not mean that it's ineffective, which is to indulge in many longish tracking shots, gliding and bobbing along in an apparent abandonment of the physics of the space they inhabit. Any film shot in a boat on water has to deal with the great conflict between keeping the horizon line steady or keeping the actors in front of that horizon steady; Adrift deals with this by introducing a third level of rocking movement, so that the camera does not seem to be rocking with the boat nor holding steady, but rocking with some other source entirely. It sounds like it should be repulsively nauseating, but it ends up being the most natural thing in the world, giving a hugely natural, environmental character to the camera that contributes to our sense of the ocean's overwhelming presence even in the shots on dry land. Hell, Richardson even manages to make that hoary old "the camera is one-quarter submerged, so occasionally it drops below the water level and we see the characters' legs, and then it bobs back up" trick that's as old as in-water cinematography do useful, interesting things. Add to that the film's excellent sound mix, which evokes the flat echoing quality of sounds in a huge empty space, as well as the constant little thuds and thwacks that happen as water smacks into a boat, wave after wave, and you have a film that evokes the omnipresence of water when you're in a boat better than anything has in a good long while. The film is not without its problems - the biggest being some questionable decisions about when to withhold information from the audience and when to provide it, as well as Claflin being completely awful and sort of wrecking the romance that is meant to be the foundation of everything else - but it's very thoughtfully made and viscerally effective for what amounts to a trashy summertime potboiler.

*I understand that this phrase is redundant.