Mommy issues

Studio 4°C doesn't have the same name recognition of the best-known and best-loved Japanese animation studios in the West, which I imagine is at least in part because its best and boldest work is at this point well over a decade in the past. But it have some irresistibly interesting credits to their name, with a killer run right at the start of its work in features: the studio's first five theatrical films, made over an eleven-year span, includes two-thirds of the 1995 anthology Memories, 1998's Spriggan, 2001's Princess Arete, 2004's Mind Game (the first feature by the magnificent Yuasa Masaaki), and 2006's Tekkonkinkreet. Not every one of those is a slam-dunk medium-redefining masterpiece, but at least the last two are, and that's enough for a pretty damn impressive batting average that should be sufficient on its own to make the release of a new Studio 4°C feature a matter of at least above-average curiosity.

I bring this up, of course, because of the release of a new Studio 4°C feature, Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko, which finally finds a new work by the studio coming out in a fairly high-profile release in the United States that hasn't been compromised by the shuttering of movie studios during a pandemic: the studio's Children of the Sea, its first collaboration with Lady Nikuko director Watanabe Ayumu (a workhorse for years, making a significant leap up in artistic ambition with that film), was one of the very first North American films to have its theatrical release postponed and ultimately cancelled in the spring of 2020. So it's cause for at least a little bit of celebration, and then a little bit more, because Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko is a very lovely domestic comedy that has enough of the stylistic edge of the studio's great triumphs of old that it feels a bit more adventuresome than its admittedly boilerplate writing would suggest.

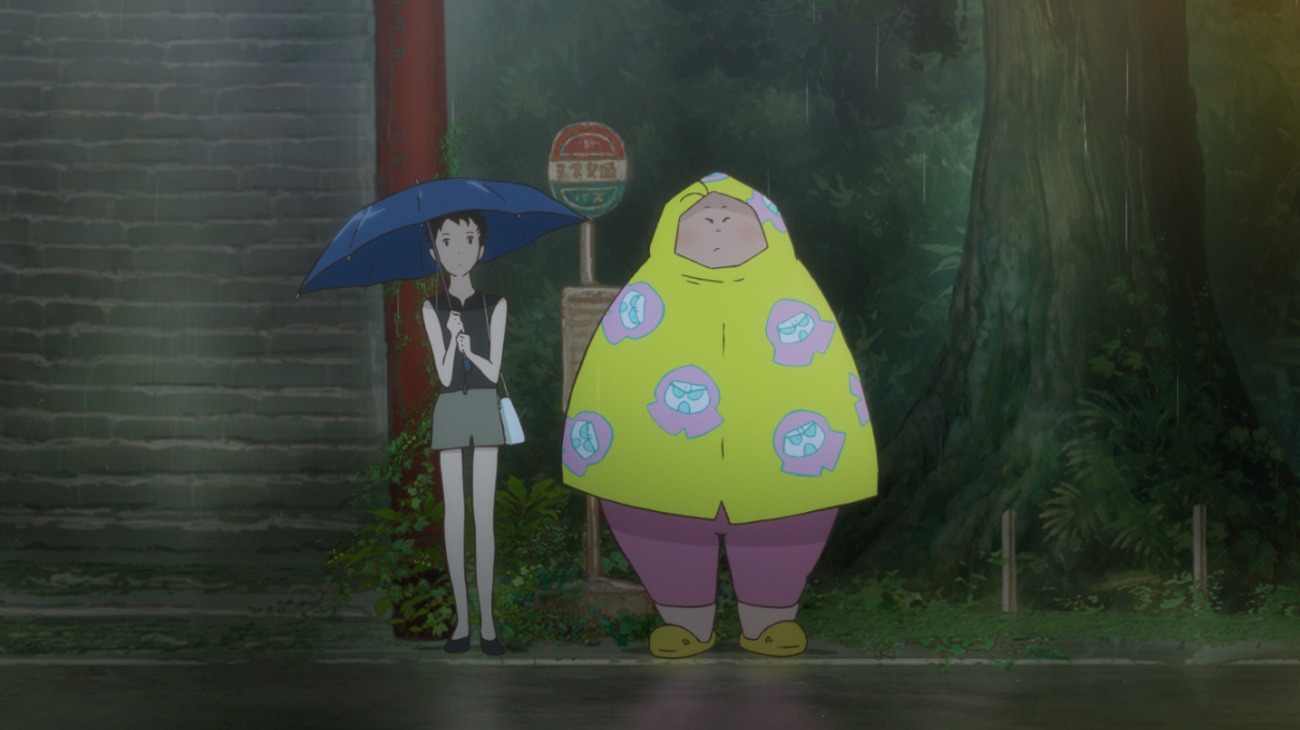

Notwithstanding the title, Nikuko (Otake Shinobu) is no lady; she's a broke single mother who has spent the last several years lurching from one crummy job in a rough part of whichever random town she finds herself, to the next job, in the next down. By the time we meet her, her daughter Kikuko (Kimura Cocomi) has become a socially awkward tween, and like all tweens, she has developed a healthy sense of mortification about her mother. This has been made all the worse for her since Nikuko is a very big personality, inside a big body: she's a loudmouth who finds everything funny, finds everything amusing, and finds everything delicious. She's an unbridled enthusiast and voracious epicure, and Kikuko's adolescent humiliation at being forever linked to this woman has led to her being as aggressively introverted and quiet as her mother is vibrant and overwhelming.

Also notwithstanding its title, Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko is in fact Kikuko's movie, and I imagine it would have to be. I can hardly imagine this being the comparison Ayumu and screenwriter Ohshima Satomi intended, in adapting Nishi Kanako's 2014 novel, but she reminds me irresistibly of Falstaff from the Henry IV plays, a massive life force of good-humored selfishness and unashamed lusts, and there's a reason why, Orson Welles notwithstanding, Falstaff has to kept as a supporting character. The point of such a figure is to be overpowering, to the audience no less than to the rest of the cast, and the emotional arc of Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko anyways needs to fall on Kikuko. Nikuko, after all, is utterly comfortable with herself from the moment we meet her, and she remains comfortable until a melodramatic third-act twist that has everything to do with Kikuko anyways. The learning and growing all falls on the daughter, who must, over the course of the film, come to appreciate Nikuko's rich vitalism as much as the film has invited us to do from its opening moments.

It's an incredibly mirthful film, taking its cues from Nikuko's trait, revealed to us in the very first moments by Kikuko's narration, of finding puns in the fabric of everyday life. It's basically turning the world into a playground, and it creates an enormous challenge for the non-speaker of Japanese, such as myself: this is a film that is completely saturated with wordplay, not just in its dialogue but in its relationship between word and image, and between sound effect and image. The subtitle translation that GKIDS has commissioned for the U.S. release does exhaustive work in trying to make this come together, but there's an unmistakable limit to how far even the most gifted translator can take us, and there are a lot of nuances to the story, emotions, and characters that are clearly getting lost, to say nothing of the vast gulf between "let me laboriously explain why this seemingly innocuous turn of phrase is in fact a joke" and "haha, that was funny". Still, that's on us dopey anglophones, not on Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko itself, and enough of the wordplay makes it through to clearly demonstrate how much joyful energy the filmmakers have poured into this, much of it erupting out in the transitions of objects into shapes and shapes into objects, and the spread of bright colors throughout.

Which gets us back to where I was going earlier, which is that this is a very intriguing exercise in taming the excessive, energetic style of Studio 4°C's best films into the formulaic beats of an angsty adolescent drama. Nikuko and Kikuko are drawn in wholly incompatible styles, to start with: Kikuko looks like a pretty stock-issue anime teen, while Nikuko has the erratic, angular shapes and messy geometry of some of the studio's bolder early work, Tekkonkinkreet especially. That's nothing more than a direct visual embodiment of the main narrative conflict between the two, but Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko goes beyond simple symbolism in playing around with the color palette and endless flexibility of form, mostly in concert with Nikuko's flights of whimsy. It's not a hugely aggressive as all that; this is still, ultimately, a low-key and at times sedate little tale about a shy adolescent, and Kikuko's scenes never have the bravura explosions of style that Nikuko's do.

But she does still have her own touches of magical whimsy: one of the film's persistent gags is that Kikuko imagines all of the sounds of the world around her - water, wind, birds - as literally speaking to her. So these sounds are all created by voice actors, giving a playful sense of animism to the world that suggests Nikuko's love of puns has descended onto Kikuko in a different form. It's a sweet touch that helps to make Kikuko a distinctive personality in her own right, something that the film struggles with initially, having given her such a routine adolescent problem, and pairing her with the far more appealing and interesting Nikuko. It allows the film to retreat from its high-energy whiz-bang playfulness into something more calm and humane, and that, in turn, pays off at the very end, when the film's main dramatic spine resolves in a very simple and intimate human moment that's communicated literally by nothing other than changing the way that one character's eyes are drawn. None of this necessarily adds up to a great, must-see triumph of anime, but it's incredibly beguiling, and more delicately layered than the simplest reading of its standard-issue scenario would suggest.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

I bring this up, of course, because of the release of a new Studio 4°C feature, Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko, which finally finds a new work by the studio coming out in a fairly high-profile release in the United States that hasn't been compromised by the shuttering of movie studios during a pandemic: the studio's Children of the Sea, its first collaboration with Lady Nikuko director Watanabe Ayumu (a workhorse for years, making a significant leap up in artistic ambition with that film), was one of the very first North American films to have its theatrical release postponed and ultimately cancelled in the spring of 2020. So it's cause for at least a little bit of celebration, and then a little bit more, because Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko is a very lovely domestic comedy that has enough of the stylistic edge of the studio's great triumphs of old that it feels a bit more adventuresome than its admittedly boilerplate writing would suggest.

Notwithstanding the title, Nikuko (Otake Shinobu) is no lady; she's a broke single mother who has spent the last several years lurching from one crummy job in a rough part of whichever random town she finds herself, to the next job, in the next down. By the time we meet her, her daughter Kikuko (Kimura Cocomi) has become a socially awkward tween, and like all tweens, she has developed a healthy sense of mortification about her mother. This has been made all the worse for her since Nikuko is a very big personality, inside a big body: she's a loudmouth who finds everything funny, finds everything amusing, and finds everything delicious. She's an unbridled enthusiast and voracious epicure, and Kikuko's adolescent humiliation at being forever linked to this woman has led to her being as aggressively introverted and quiet as her mother is vibrant and overwhelming.

Also notwithstanding its title, Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko is in fact Kikuko's movie, and I imagine it would have to be. I can hardly imagine this being the comparison Ayumu and screenwriter Ohshima Satomi intended, in adapting Nishi Kanako's 2014 novel, but she reminds me irresistibly of Falstaff from the Henry IV plays, a massive life force of good-humored selfishness and unashamed lusts, and there's a reason why, Orson Welles notwithstanding, Falstaff has to kept as a supporting character. The point of such a figure is to be overpowering, to the audience no less than to the rest of the cast, and the emotional arc of Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko anyways needs to fall on Kikuko. Nikuko, after all, is utterly comfortable with herself from the moment we meet her, and she remains comfortable until a melodramatic third-act twist that has everything to do with Kikuko anyways. The learning and growing all falls on the daughter, who must, over the course of the film, come to appreciate Nikuko's rich vitalism as much as the film has invited us to do from its opening moments.

It's an incredibly mirthful film, taking its cues from Nikuko's trait, revealed to us in the very first moments by Kikuko's narration, of finding puns in the fabric of everyday life. It's basically turning the world into a playground, and it creates an enormous challenge for the non-speaker of Japanese, such as myself: this is a film that is completely saturated with wordplay, not just in its dialogue but in its relationship between word and image, and between sound effect and image. The subtitle translation that GKIDS has commissioned for the U.S. release does exhaustive work in trying to make this come together, but there's an unmistakable limit to how far even the most gifted translator can take us, and there are a lot of nuances to the story, emotions, and characters that are clearly getting lost, to say nothing of the vast gulf between "let me laboriously explain why this seemingly innocuous turn of phrase is in fact a joke" and "haha, that was funny". Still, that's on us dopey anglophones, not on Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko itself, and enough of the wordplay makes it through to clearly demonstrate how much joyful energy the filmmakers have poured into this, much of it erupting out in the transitions of objects into shapes and shapes into objects, and the spread of bright colors throughout.

Which gets us back to where I was going earlier, which is that this is a very intriguing exercise in taming the excessive, energetic style of Studio 4°C's best films into the formulaic beats of an angsty adolescent drama. Nikuko and Kikuko are drawn in wholly incompatible styles, to start with: Kikuko looks like a pretty stock-issue anime teen, while Nikuko has the erratic, angular shapes and messy geometry of some of the studio's bolder early work, Tekkonkinkreet especially. That's nothing more than a direct visual embodiment of the main narrative conflict between the two, but Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko goes beyond simple symbolism in playing around with the color palette and endless flexibility of form, mostly in concert with Nikuko's flights of whimsy. It's not a hugely aggressive as all that; this is still, ultimately, a low-key and at times sedate little tale about a shy adolescent, and Kikuko's scenes never have the bravura explosions of style that Nikuko's do.

But she does still have her own touches of magical whimsy: one of the film's persistent gags is that Kikuko imagines all of the sounds of the world around her - water, wind, birds - as literally speaking to her. So these sounds are all created by voice actors, giving a playful sense of animism to the world that suggests Nikuko's love of puns has descended onto Kikuko in a different form. It's a sweet touch that helps to make Kikuko a distinctive personality in her own right, something that the film struggles with initially, having given her such a routine adolescent problem, and pairing her with the far more appealing and interesting Nikuko. It allows the film to retreat from its high-energy whiz-bang playfulness into something more calm and humane, and that, in turn, pays off at the very end, when the film's main dramatic spine resolves in a very simple and intimate human moment that's communicated literally by nothing other than changing the way that one character's eyes are drawn. None of this necessarily adds up to a great, must-see triumph of anime, but it's incredibly beguiling, and more delicately layered than the simplest reading of its standard-issue scenario would suggest.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!