Street kids

I won't go so far as to say that there's nothing that can prepare you for Tekkonkinkreet, the 2006 film that, among its many traits, was the first significant Japanese-produced animated feature directed by a non-Japanese person (the man with that honor was Los Angeles-born Michael Arias, who got his start in visual effects and animation software design, before producing the 2003 animation anthology The Animatrix). There is in fact one thing that can prepare you for it very well: this was the very next film animated by Studio 4°C after the 2004 Mind Game, the first feature by Yuasa Masaaki, and it is very clear that the studio was applying the knowledge learned from that project on this one. Mind you, when the precedent for a film is that it borrows a little bit (mostly character design) from what might very well be the single most visually outré animated feature ever made, we're definitely not in "this is a normal-looking movie that does normal things" territory.

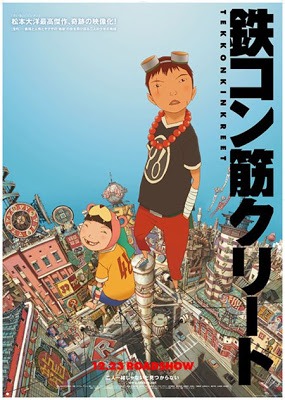

And indeed, Tekkonkinkreet is one of the most wholeheartedly and joyfully abnormal animated features of the 2000s. I am not familiar with Matsumoto Taiyo's manga, which ran from 1993-'94; my sense is that Anthony Weintraub's screenplay follows the plot fairly closely, and that the style draws only a little bit from the artwork. Certainly given that the book was published in black-and-white, the film's visual style can't be too indebted to it: one of the foremost traits of Tekkonkinkreet the movie is that it is intensely, eye-meltingly oversaturated, as bright and shining in its palette of primary colors as any movie could be. It's a top-notch example of the vast difference in how the Japanese animation industry took to using digital technologies compared to Hollywood: in this case, it's all about locking in the boldest, strongest hue through digital painting, creating a film that looks absolutely nothing like a handmade painting: it glows too much for that. The result is an extraordinarily striking, rich, vibrant world, one that seems more alive than life itself, almost uncanny in its vividness. And this ends up suiting the needs of the narrative in addition to being extremely pleasurable to look at in its own right. On top of this, the film is very aggressive in using three-dimensional CGI backgrounds (painted to look flat), a common enough trick in later anime feature, but rarely employed so vigorously as we see here: the camera races around at top speed, overshooting the characters as it look for them, floating and bobbing with no concern at all for gravity.

This is all to the best interest of a film that is, in large part, about representing a location. The film takes place in Treasure Town, a place that combines all the best East Asian world cities in a blender; the impression one gets is that it was a really spectacular, state-of-the-art place to live 20 or 30 years ago, but the march of time, economic collapse, and the rise of powerful crime syndicates have left it as a dystopic slum. Still, there's enough of the wonders that were for the place to remain brightly colored and full of sleek futuristic lines. Here, we find a pair of homeless orphans: teenage Black (Ninomiya Kazunari), prone to violence and territorial rage, modulated only by his protective stance towards 11-year-old White (Aoi Yu), who remains lighthearted and prone to flights of childlike fancy even in this hell world. Alongside this runs a parallel plot about the gangsters whose organization is trying to bulldoze Treasure Town, told mostly through the low-level criminal Kimura (Iseya Yusuke) and his mentor, the aging gangster Rat (Tanaka Min); they come into conflict with Black and White because of this, though it's not necessarily the most important thing going on in either thread.

Both stories circle around different ways of approaching the question, of what value is a place? For Kimura and the people around him, the slum is a gritty, spoiled urban wasteland, and their plotline accordingly follows the cruel rules of film noir or any other tradition of urban crime narratives you can name. For Black and White, Treasure Town is their home, full of excitement and danger and possibility, and so their plotline emphasises all the ways that urban squalor and ebullient wonder and imagination can co-exist - and hence we get all those luminous colors and that weightless sense of space. Tekkonkinkreet (a title derived from a mispronunciation of the Japanese for "reinforced concrete", making it clear just how much importance we're to put on the urban landscape itself) is not blind to the horrible, violent realities facing its young protagonists; for that matter, Black isn't blind to it himself. But it's also not looking to tell us a sober neorealist tale about the suffering that goes on in such places. It's a film of energy and savage joy, and in its treatment of the relationship between the two boys, it even manages to be sweet and tender, finding something noble and loving even in Black's reversion to an almost animalistic fury when he needs to defend White.

The style bringing this story to life is just as much of a marriage between sweetness and viciousness. The character design is extraordinary, rendering human bodies as sharp, slashing objects made up of points and angles; their legs taper into little fang-like representations of feet, their faces are geometric blocks with harshly-scrawled line drawings for faces that are then given texture and depth through the very lovely use of color and painting. The character drawings are brutal and crude, animated at a persistently low frame-rate that contrasts with the fluidity of the moving background to exaggerate the jerky movement of people even more than in other limited animation from Japan, the country where limited animation became high art. This is to say, there's a rawness to the characters, something violent and urgent, that both accentuates and conflicts with the buoyant color scheme and the digitally smoothed environments.

That conflict is at the heart of Tekkonkinkreet's whole project, which is both joyous and bitter, depending on the moment; it admires the young protagonists for the indefatigable spirits while being repulsed by the life they live, and even the actions they have to take to preserve that life. It is, ultimately, a film about the failure of urban spaces to provide for their residents, but the pleasures that still exist in those spaces, filtered through a boys' own adventure-cum-yakuza adventure with loose sci-fi overtones, and the tension between the stunning, spectacular fun of the film and the gravity of its content give the whole thing a remarkable nervous energy that never resolves. It's a real one-of-a-kind movie, with a remarkable animation aesthetic like nothing else out there; but the way it approaches its boilerplate story isn't all that much weaker, honestly.

And indeed, Tekkonkinkreet is one of the most wholeheartedly and joyfully abnormal animated features of the 2000s. I am not familiar with Matsumoto Taiyo's manga, which ran from 1993-'94; my sense is that Anthony Weintraub's screenplay follows the plot fairly closely, and that the style draws only a little bit from the artwork. Certainly given that the book was published in black-and-white, the film's visual style can't be too indebted to it: one of the foremost traits of Tekkonkinkreet the movie is that it is intensely, eye-meltingly oversaturated, as bright and shining in its palette of primary colors as any movie could be. It's a top-notch example of the vast difference in how the Japanese animation industry took to using digital technologies compared to Hollywood: in this case, it's all about locking in the boldest, strongest hue through digital painting, creating a film that looks absolutely nothing like a handmade painting: it glows too much for that. The result is an extraordinarily striking, rich, vibrant world, one that seems more alive than life itself, almost uncanny in its vividness. And this ends up suiting the needs of the narrative in addition to being extremely pleasurable to look at in its own right. On top of this, the film is very aggressive in using three-dimensional CGI backgrounds (painted to look flat), a common enough trick in later anime feature, but rarely employed so vigorously as we see here: the camera races around at top speed, overshooting the characters as it look for them, floating and bobbing with no concern at all for gravity.

This is all to the best interest of a film that is, in large part, about representing a location. The film takes place in Treasure Town, a place that combines all the best East Asian world cities in a blender; the impression one gets is that it was a really spectacular, state-of-the-art place to live 20 or 30 years ago, but the march of time, economic collapse, and the rise of powerful crime syndicates have left it as a dystopic slum. Still, there's enough of the wonders that were for the place to remain brightly colored and full of sleek futuristic lines. Here, we find a pair of homeless orphans: teenage Black (Ninomiya Kazunari), prone to violence and territorial rage, modulated only by his protective stance towards 11-year-old White (Aoi Yu), who remains lighthearted and prone to flights of childlike fancy even in this hell world. Alongside this runs a parallel plot about the gangsters whose organization is trying to bulldoze Treasure Town, told mostly through the low-level criminal Kimura (Iseya Yusuke) and his mentor, the aging gangster Rat (Tanaka Min); they come into conflict with Black and White because of this, though it's not necessarily the most important thing going on in either thread.

Both stories circle around different ways of approaching the question, of what value is a place? For Kimura and the people around him, the slum is a gritty, spoiled urban wasteland, and their plotline accordingly follows the cruel rules of film noir or any other tradition of urban crime narratives you can name. For Black and White, Treasure Town is their home, full of excitement and danger and possibility, and so their plotline emphasises all the ways that urban squalor and ebullient wonder and imagination can co-exist - and hence we get all those luminous colors and that weightless sense of space. Tekkonkinkreet (a title derived from a mispronunciation of the Japanese for "reinforced concrete", making it clear just how much importance we're to put on the urban landscape itself) is not blind to the horrible, violent realities facing its young protagonists; for that matter, Black isn't blind to it himself. But it's also not looking to tell us a sober neorealist tale about the suffering that goes on in such places. It's a film of energy and savage joy, and in its treatment of the relationship between the two boys, it even manages to be sweet and tender, finding something noble and loving even in Black's reversion to an almost animalistic fury when he needs to defend White.

The style bringing this story to life is just as much of a marriage between sweetness and viciousness. The character design is extraordinary, rendering human bodies as sharp, slashing objects made up of points and angles; their legs taper into little fang-like representations of feet, their faces are geometric blocks with harshly-scrawled line drawings for faces that are then given texture and depth through the very lovely use of color and painting. The character drawings are brutal and crude, animated at a persistently low frame-rate that contrasts with the fluidity of the moving background to exaggerate the jerky movement of people even more than in other limited animation from Japan, the country where limited animation became high art. This is to say, there's a rawness to the characters, something violent and urgent, that both accentuates and conflicts with the buoyant color scheme and the digitally smoothed environments.

That conflict is at the heart of Tekkonkinkreet's whole project, which is both joyous and bitter, depending on the moment; it admires the young protagonists for the indefatigable spirits while being repulsed by the life they live, and even the actions they have to take to preserve that life. It is, ultimately, a film about the failure of urban spaces to provide for their residents, but the pleasures that still exist in those spaces, filtered through a boys' own adventure-cum-yakuza adventure with loose sci-fi overtones, and the tension between the stunning, spectacular fun of the film and the gravity of its content give the whole thing a remarkable nervous energy that never resolves. It's a real one-of-a-kind movie, with a remarkable animation aesthetic like nothing else out there; but the way it approaches its boilerplate story isn't all that much weaker, honestly.