I can't help falling in love with you

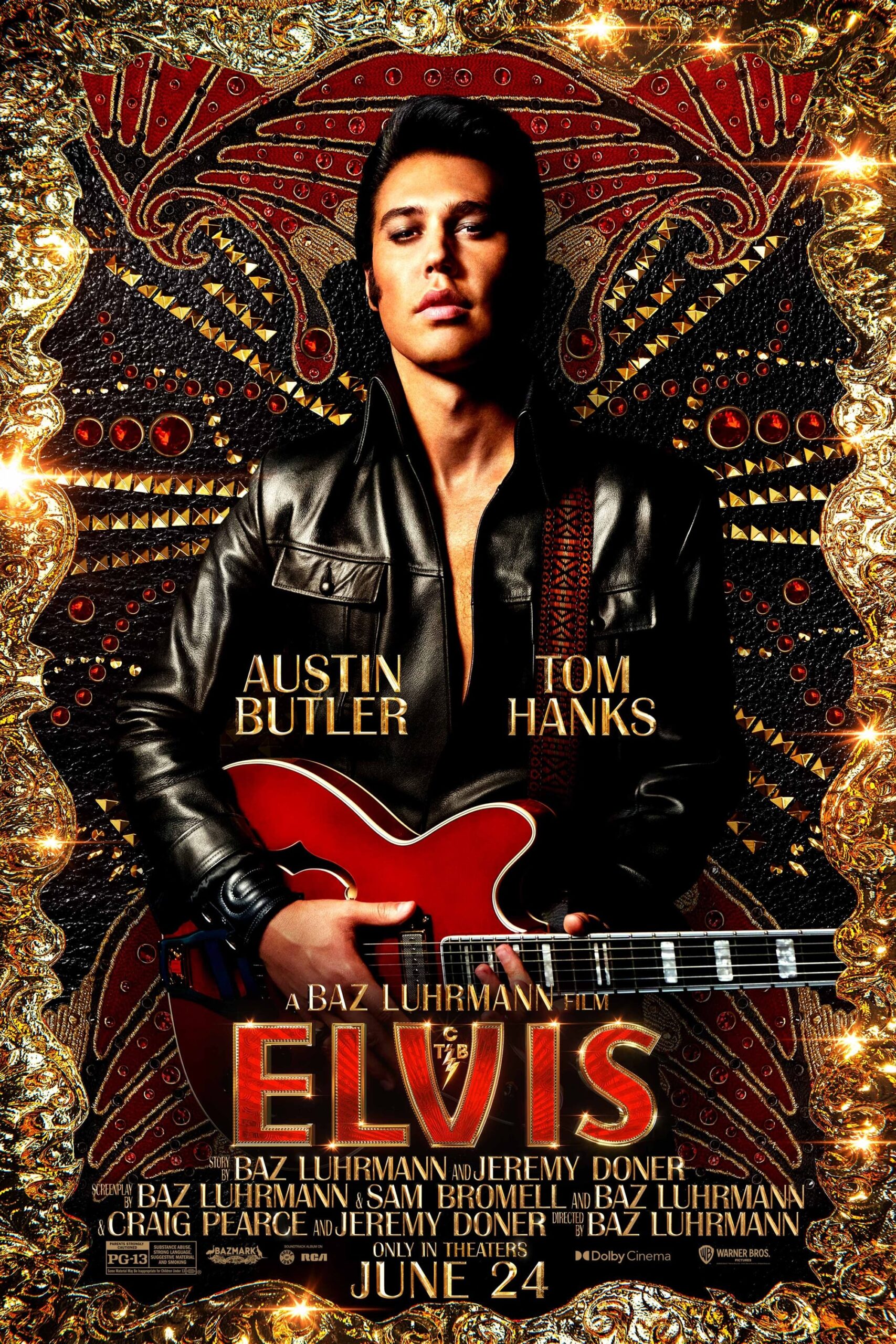

The grand-scale spectacular biopic Elvis (the fourth narrative treatment of the life of Elvis Presley in any filmed medium to go by that precise title, and at 159 minutes, somehow, also the shortest*) is the first feature directed by Baz Luhrmann in the nine years since The Great Gatsby. It's been considerably longer since his last feature that was good and worth watching: depending on where you come down on Australia, it's been more than two full decades, in fact, with Moulin Rouge! having turned 21 years old in the same month that Elvis was released. That's a very long time to go without having a proper project from English-language cinema's foremost maximalist sensualist, and thus the best news first: Elvis is a hell of a good Baz Luhrmann film. It's also a pretty damn good Elvis Presley film, for that matter, and it's a little bit surprising that those two things aren't more directly in conflict with each other.

The good Luhrmann parts first: literally, in fact, since the opening 15 or 20 minutes of Elvis feel somewhat like a direct remake of the opening 15 or 20 minutes of Moulin Rouge!, and they're also barely about Elvis Presley (played here by Austin Butler, who has been toiling away for years, mostly in television for young adolescents, and is pretty clearly set to become a much bigger deal on the back of this film). The film opens 20 years after his death at age 42, in fact, in a hospital room overlooking the '90s family-friendly version of Las Vegas (Star Trek: The Experience, housed at the time in the hotel where Presley held his celebrated series of Vegas shows starting in 1969, receives a bizarre amount of attention†). Here, a vampire mummy (Tom Hanks) shuffles around, surrounded either by the relics of his life or a montage of the now-forgotten items he used to define himself by; a slurry relationship between "what is" and "what is being subjectively brought into focus by editing that collapses diegetic and non-diegetic elements" is common in Elvis, and it's very nearly the only way the opening few minutes are structured at all. This is very much the "Luhrmann" part of it, and I think there's a real possibility that editors Jonathan Redmond and Matt Villa are the two people most responsible for the film's success, despite their only prior work together coming on The Great Gatsby, the worst-edited of the director's films.

At some point in here, the mummy tells us, in an hypnotic Mitteleuropean accent that Hanks dredged up from God knows where (it's "supposed" to be Dutch, and it's probably just as close to that as it is to a dozen other things) that he's none other than Colonel Tom Parker, the promoter and manager who controlled Presley with an otherworldly amount of control for virtually his entire career, mismanaging into oblivion the considerable fortune that comes from being the bestselling solo artist in the history of music. Parker is talking directly to "us" - "us" being Elvis fans in 1997, or "us" being movie audiences in 2022, or "us" being every person who is still more connected to their sense of human kindness than the self-aggrandising predator spitting out the narration, it's impossible to say. But he thinks we're giant pieces of shit - and letting us know that we have it all wrong, he's not the monster who wrung the life out of Elvis and left him to die, the way the popular telling of the rock star's life would have it be. To prove it, he launches into a 159-minute narrative in which he himself comes across as some ancient gargoyle-like menace, a collection of sweaty jowls perched beneath the stabbing eyes and hungry teeth of a massive viper. So much for trying to prove us we're wrong.

I do greatly adore Hanks's work here; it's in the top 3 weirdest performances he's ever given (Cloud Atlas is weirder still, and I think The Ladykillers is pretty close to tied with this). He slides right into the stylistic extravagance and unrestrained, wantonly undisciplined all-the-movie-all-the-time madness that Luhrmann clearly has in mind for this character, who is not so much a representation of the actual human being, however much of a conman and liar responsible for many of the terrible things he's denying, as he is an embodiment of the spirit of exploitative Avarice. He resembles a mixture of the villain from a silent Soviet propaganda film, a Kentucky racehorse breeder, and Jabba the Hutt. Introducing himself to us through his career as a carnival huckster, he proudly describes his great work as a "snow man", confidently distracting audiences with appeals to their basest instincts.

Hanks is having a blast playing one of the few out-and-out villains of his career as a grandiose live-action cartoon, made-up to look like a sweaty, corpulent toad, and sneering at us in his loopy affected voice. It's a maximalist performance that matches well with Luhrmann's positioning of the character as the rotten, obese id of American entrepreneurship, a creature designed only to exploit talent for easy money, sucking it dry and leaving it a husk. Nothing about this is subtle - nothing in all of Luhrmann is subtle, but Hanks's balls-out performance is unsubtle even by the director's standards. A good moment comes early on, when Parker learns that the soulful young man singing "That's All Right" is in fact white, and therefore can be sold to white audiences who would be scandalised to purchase an album of "Black Music": "He's white?" growls Hanks in a hungry daze that sounds like it's had the bass digitally boosted, while the camera pushes in straight to his face, and I think the image darkens, though maybe I was just overwriting it that way in my brain. It is a bit impressive that Luhrmann resisted the impulse to have Hanks's eyes spin around like the tumblers in a slot machine and come up as dollar signs.

A terrifically ungainly, preposterous performance of a warped character in a film that, as long as it focuses on Parker's hostile narration, is a real whirlwind of stimulation. Elvis collides images in long dissolves, throws up garish title cards, cuts scenes into small pieces and turns them into little mini-montages, and generally feels exactly like the druggy memories of an angry man reliving his greatest triumph. The first time we see Butler's Elvis in full (preceded with plenty of old-school "LOOK AT HOW WE'RE NOT SHOWING YOU HIS FACE" hokum, of the best sort is a terrific little musical number, sparingly staged but with footage cut and manipulated to have a dizzying effect visually, perfectly matching the orgasmic intensity with which the sound mix amplifies the over-the-top performances of the extras. Stuff like that.

As long as it focuses on Parker. The fact of the matter is, though, that Elvis is a biopic of Elvis, and it is by and large a good one. Butler's performance is terrific, both as mimicry of one of the 20th Century's most famous and recognisable humans, and as a way of digging out the actual psychology behind the mushy speech and squirmy body language. He plays Presley as a basically shy and unconfident kid who became a superstar before he became emotionally prepared for dealing with superstardom, leading him to overrely on Parker as a guardian devil; it's a small kernel of relatable humanity in the midst of the film's kaleidscope of visual excess and blunt-force emotional tones. He even manages to hold steady when the bottom drops out and the film gets to the Unrelenting Drug Abuse years; given a chance to go big and over the top, Butler mostly tries to stay grounded in the physicality of his performance and the emotions he's already laid into the character. It's much better than the baseline of "impersonating a famous person in the hopes of Oscar glory" performances, even though it's still basically that; even more importantly, it's a counterweight to the extreme Tom Hanksness of it all, making sure that the film is still trafficking in real feelings, and not just a garish pantomime of feelings.

Butler's performance, good as it is, doesn't entirely hide what a by-the-books script the film has, though. Written by a rat's nest of writers (the screenplay credits go to Baz Luhrmann & Sam Bromell and Baz Luhrmann [again] & Craig Pearce and Jeremy Doner; the story credits go to Luhrmann and Doner. So we're looking at at least three distinct layers of drafts that got cobbled together), the film is quite unafraid of all the usual biopic clichés, and at 159 minutes, it can indulge them all at great length. To some extent, the filmmaking covers for the flimsy writing - not just the hyperactive editing, but also things like the way Catherine Martin and Karen Murphy's production design creates a kind of "storybook" realism out of the film's real-world locations, where they basically look as they did in reality, but have been romanticised a bit in the colors, the lines, and the "bigness" of them (the bustling and cramped version of Beale Street in Memphis, is a good example of this, especially as augmented by high-contrast lighting between the starkly sunshiney exteriors and the romantically gloomy interiors. So is the very specific instance of the sign outside the International Hotel in Vegas, which is staged and shot like a religious shrine). The musical performances, a mainstay of the musician biopic, also rise above the genre, both from the cutting and cinematographer Mandy Walker's camerawork, but also the terrific music editing, which blends Butler's voice, Presley's recordings, and contemporary music forms to create something almost impressionistic out of some of the most familiar songs in American history.

Still, there's only so much that can be done with some of this material, and there are places where Luhrmann and company just flat-out give up; Butler seems to be the only person who isn't taking the path of least resistance in cramming the drug material in there, for example. I would hardly say that there's enough of this to ruin Elvis, but there's certainly enough to make it feel like we didn't get the "most" version of this movie we could have, and that 159 minutes is quite a stupid amount of time for a fairly straightforward story that is in some way the Ur-text of out of control musician biopics.

But then, Luhrmann never met a straightforward, overfamiliar story he couldn't use as the pretext for creating a warped and stylised meditation on the themes of that story. Elvis is a little bit like his 1996 breakthrough William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet in that regard: it's less about telling Elvis Presley's story, than about using that story's familiarity as a way of digging into the big primordial Stuff fueling that story. In this case, it's all about the notion of pop stardom, the frenzy and glamor and libidinous energy, and the filthy ugly greed and exploitation, all spun up into a whirlwind of style that's giddy and ecstatic right until it crashes down into something harrowing and grossly unsatisfying at the end. Luhrmann's thing isn't to tease out sensitive emotions from his scenarios, but to plaster Big Fucking Feelings all over those scenarios in gorgeously garish colors and general sensory overload. And he's doing that here as a way of exploring the feelings of aesthetic pleasure and sexual desire and vicarious luxury that Presley specifically and music stars in general whip up in their fans, all of it bold-faced and italicised and blasted out through a bullhorn. It's easy to understand why someone would find that tiresome and unsophisticated and trashy, but I love the hell out of it, and it's the mode that Elvis is triumphing in for a good two-thirds of its massive bloat of a running time.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

*The best-known of the others is undoubtedly the 1979 telefilm Elvis, directed by John Carpenter and starring Kurt Russell. Then comes the 2005 two-part TV miniseries Elvis, starring Jonathan Rhys Meyers, and then a clear-cut last place with the obscure 1990 TV series Elvis, which focused on the very start of Presley's professional career, and was cancelled before it could air all ten of its produced episodes.

†Nor will this be the last time that the film reveals a peculiar fixation on Star Trek: during a long, tense scene set during the contentious production of Presley's 1968 comeback special on NBC, there are two well-lit and in-focus posters on the back wall of Trek actors in costume, one of William Shatner & Leonard Nimoy, the other of Nichelle Nichols. I literally cannot imagine what the hell this is about.

The good Luhrmann parts first: literally, in fact, since the opening 15 or 20 minutes of Elvis feel somewhat like a direct remake of the opening 15 or 20 minutes of Moulin Rouge!, and they're also barely about Elvis Presley (played here by Austin Butler, who has been toiling away for years, mostly in television for young adolescents, and is pretty clearly set to become a much bigger deal on the back of this film). The film opens 20 years after his death at age 42, in fact, in a hospital room overlooking the '90s family-friendly version of Las Vegas (Star Trek: The Experience, housed at the time in the hotel where Presley held his celebrated series of Vegas shows starting in 1969, receives a bizarre amount of attention†). Here, a vampire mummy (Tom Hanks) shuffles around, surrounded either by the relics of his life or a montage of the now-forgotten items he used to define himself by; a slurry relationship between "what is" and "what is being subjectively brought into focus by editing that collapses diegetic and non-diegetic elements" is common in Elvis, and it's very nearly the only way the opening few minutes are structured at all. This is very much the "Luhrmann" part of it, and I think there's a real possibility that editors Jonathan Redmond and Matt Villa are the two people most responsible for the film's success, despite their only prior work together coming on The Great Gatsby, the worst-edited of the director's films.

At some point in here, the mummy tells us, in an hypnotic Mitteleuropean accent that Hanks dredged up from God knows where (it's "supposed" to be Dutch, and it's probably just as close to that as it is to a dozen other things) that he's none other than Colonel Tom Parker, the promoter and manager who controlled Presley with an otherworldly amount of control for virtually his entire career, mismanaging into oblivion the considerable fortune that comes from being the bestselling solo artist in the history of music. Parker is talking directly to "us" - "us" being Elvis fans in 1997, or "us" being movie audiences in 2022, or "us" being every person who is still more connected to their sense of human kindness than the self-aggrandising predator spitting out the narration, it's impossible to say. But he thinks we're giant pieces of shit - and letting us know that we have it all wrong, he's not the monster who wrung the life out of Elvis and left him to die, the way the popular telling of the rock star's life would have it be. To prove it, he launches into a 159-minute narrative in which he himself comes across as some ancient gargoyle-like menace, a collection of sweaty jowls perched beneath the stabbing eyes and hungry teeth of a massive viper. So much for trying to prove us we're wrong.

I do greatly adore Hanks's work here; it's in the top 3 weirdest performances he's ever given (Cloud Atlas is weirder still, and I think The Ladykillers is pretty close to tied with this). He slides right into the stylistic extravagance and unrestrained, wantonly undisciplined all-the-movie-all-the-time madness that Luhrmann clearly has in mind for this character, who is not so much a representation of the actual human being, however much of a conman and liar responsible for many of the terrible things he's denying, as he is an embodiment of the spirit of exploitative Avarice. He resembles a mixture of the villain from a silent Soviet propaganda film, a Kentucky racehorse breeder, and Jabba the Hutt. Introducing himself to us through his career as a carnival huckster, he proudly describes his great work as a "snow man", confidently distracting audiences with appeals to their basest instincts.

Hanks is having a blast playing one of the few out-and-out villains of his career as a grandiose live-action cartoon, made-up to look like a sweaty, corpulent toad, and sneering at us in his loopy affected voice. It's a maximalist performance that matches well with Luhrmann's positioning of the character as the rotten, obese id of American entrepreneurship, a creature designed only to exploit talent for easy money, sucking it dry and leaving it a husk. Nothing about this is subtle - nothing in all of Luhrmann is subtle, but Hanks's balls-out performance is unsubtle even by the director's standards. A good moment comes early on, when Parker learns that the soulful young man singing "That's All Right" is in fact white, and therefore can be sold to white audiences who would be scandalised to purchase an album of "Black Music": "He's white?" growls Hanks in a hungry daze that sounds like it's had the bass digitally boosted, while the camera pushes in straight to his face, and I think the image darkens, though maybe I was just overwriting it that way in my brain. It is a bit impressive that Luhrmann resisted the impulse to have Hanks's eyes spin around like the tumblers in a slot machine and come up as dollar signs.

A terrifically ungainly, preposterous performance of a warped character in a film that, as long as it focuses on Parker's hostile narration, is a real whirlwind of stimulation. Elvis collides images in long dissolves, throws up garish title cards, cuts scenes into small pieces and turns them into little mini-montages, and generally feels exactly like the druggy memories of an angry man reliving his greatest triumph. The first time we see Butler's Elvis in full (preceded with plenty of old-school "LOOK AT HOW WE'RE NOT SHOWING YOU HIS FACE" hokum, of the best sort is a terrific little musical number, sparingly staged but with footage cut and manipulated to have a dizzying effect visually, perfectly matching the orgasmic intensity with which the sound mix amplifies the over-the-top performances of the extras. Stuff like that.

As long as it focuses on Parker. The fact of the matter is, though, that Elvis is a biopic of Elvis, and it is by and large a good one. Butler's performance is terrific, both as mimicry of one of the 20th Century's most famous and recognisable humans, and as a way of digging out the actual psychology behind the mushy speech and squirmy body language. He plays Presley as a basically shy and unconfident kid who became a superstar before he became emotionally prepared for dealing with superstardom, leading him to overrely on Parker as a guardian devil; it's a small kernel of relatable humanity in the midst of the film's kaleidscope of visual excess and blunt-force emotional tones. He even manages to hold steady when the bottom drops out and the film gets to the Unrelenting Drug Abuse years; given a chance to go big and over the top, Butler mostly tries to stay grounded in the physicality of his performance and the emotions he's already laid into the character. It's much better than the baseline of "impersonating a famous person in the hopes of Oscar glory" performances, even though it's still basically that; even more importantly, it's a counterweight to the extreme Tom Hanksness of it all, making sure that the film is still trafficking in real feelings, and not just a garish pantomime of feelings.

Butler's performance, good as it is, doesn't entirely hide what a by-the-books script the film has, though. Written by a rat's nest of writers (the screenplay credits go to Baz Luhrmann & Sam Bromell and Baz Luhrmann [again] & Craig Pearce and Jeremy Doner; the story credits go to Luhrmann and Doner. So we're looking at at least three distinct layers of drafts that got cobbled together), the film is quite unafraid of all the usual biopic clichés, and at 159 minutes, it can indulge them all at great length. To some extent, the filmmaking covers for the flimsy writing - not just the hyperactive editing, but also things like the way Catherine Martin and Karen Murphy's production design creates a kind of "storybook" realism out of the film's real-world locations, where they basically look as they did in reality, but have been romanticised a bit in the colors, the lines, and the "bigness" of them (the bustling and cramped version of Beale Street in Memphis, is a good example of this, especially as augmented by high-contrast lighting between the starkly sunshiney exteriors and the romantically gloomy interiors. So is the very specific instance of the sign outside the International Hotel in Vegas, which is staged and shot like a religious shrine). The musical performances, a mainstay of the musician biopic, also rise above the genre, both from the cutting and cinematographer Mandy Walker's camerawork, but also the terrific music editing, which blends Butler's voice, Presley's recordings, and contemporary music forms to create something almost impressionistic out of some of the most familiar songs in American history.

Still, there's only so much that can be done with some of this material, and there are places where Luhrmann and company just flat-out give up; Butler seems to be the only person who isn't taking the path of least resistance in cramming the drug material in there, for example. I would hardly say that there's enough of this to ruin Elvis, but there's certainly enough to make it feel like we didn't get the "most" version of this movie we could have, and that 159 minutes is quite a stupid amount of time for a fairly straightforward story that is in some way the Ur-text of out of control musician biopics.

But then, Luhrmann never met a straightforward, overfamiliar story he couldn't use as the pretext for creating a warped and stylised meditation on the themes of that story. Elvis is a little bit like his 1996 breakthrough William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet in that regard: it's less about telling Elvis Presley's story, than about using that story's familiarity as a way of digging into the big primordial Stuff fueling that story. In this case, it's all about the notion of pop stardom, the frenzy and glamor and libidinous energy, and the filthy ugly greed and exploitation, all spun up into a whirlwind of style that's giddy and ecstatic right until it crashes down into something harrowing and grossly unsatisfying at the end. Luhrmann's thing isn't to tease out sensitive emotions from his scenarios, but to plaster Big Fucking Feelings all over those scenarios in gorgeously garish colors and general sensory overload. And he's doing that here as a way of exploring the feelings of aesthetic pleasure and sexual desire and vicarious luxury that Presley specifically and music stars in general whip up in their fans, all of it bold-faced and italicised and blasted out through a bullhorn. It's easy to understand why someone would find that tiresome and unsophisticated and trashy, but I love the hell out of it, and it's the mode that Elvis is triumphing in for a good two-thirds of its massive bloat of a running time.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

*The best-known of the others is undoubtedly the 1979 telefilm Elvis, directed by John Carpenter and starring Kurt Russell. Then comes the 2005 two-part TV miniseries Elvis, starring Jonathan Rhys Meyers, and then a clear-cut last place with the obscure 1990 TV series Elvis, which focused on the very start of Presley's professional career, and was cancelled before it could air all ten of its produced episodes.

†Nor will this be the last time that the film reveals a peculiar fixation on Star Trek: during a long, tense scene set during the contentious production of Presley's 1968 comeback special on NBC, there are two well-lit and in-focus posters on the back wall of Trek actors in costume, one of William Shatner & Leonard Nimoy, the other of Nichelle Nichols. I literally cannot imagine what the hell this is about.