This is a story about love

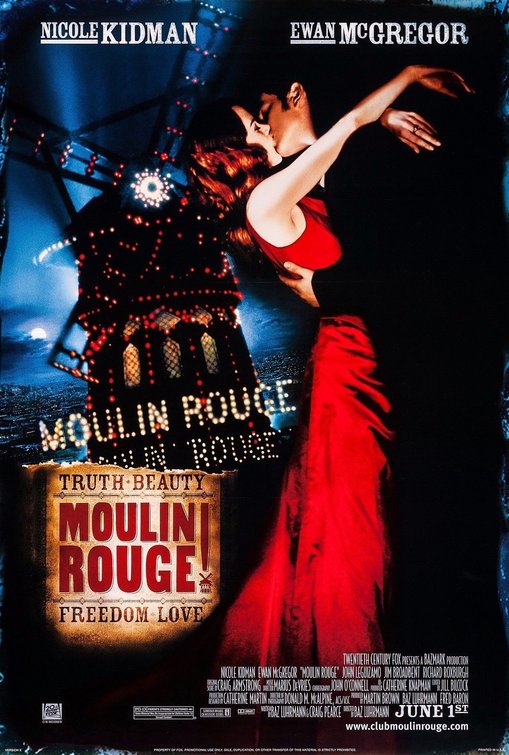

There is a very real possibility that out of the several thousand movies I've watched in my life, most of them in the twelve years since I was a wee film school freshman, Baz Luhrmann's candy-colored, hyperactive post-modern musical Moulin Rouge! has had more of an impact on me than anything else. Partially this is because it came out at the exact perfect time for a movie to make that kind of impact - the end of my first year at school, when I was at the exceptionally formative age of 19 - and it's probably fair to say that if Moulin Rouge! hadn't done the job, something else would have, and we'd be here for the inaugural essay on the films in my own personal canon discussing something else. Like, I don't know, Shrek, or something.

But the point is, I saw Moulin Rouge! (the punctuation is important for two reasons: to emphasise the film's non-stop madcap pace, and to distinguish it from John Huston's soporific Moulin Rouge of 1952) under circumstances that remain particularly memorable to me - it was the first time I'd ever really spent time with a now very dear friend, and the walk back from the movie theater included the first conversation I ever had about what special features I expected to show up on the future DVD (which, in the event, was a particularly well-stocked one; and, better yet, came out on my 20th birthday, which I took to be a good omen) - and it taught me the single most important lesson that I could have ever learned on the way to becoming the particular sort of cinephile I am today: that there could be a movie I loved for its energy, its color and lushness, its performances, its visual sense of humor, its manic editing, its commitment to bringing the long-dead musical genre back to life in a vigorously contemporary idiom without feeling hollow and hip - that there could be a movie that would so thoroughly delight me that even today, it's intractably on my Desert Island Top 10. And that it could be all of this despite possessing an unbelievably dumb script. And, in fairness, a purposefully unbelievably dumb script, but the fact remains that nobody could get away with calling Moulin Rouge! a triumph of screenwriting. This sudden, shocked understanding that I could - and did! - adore a film for reasons that had nothing at all to do with its narrative underlies pretty much all of the feelings I have towards movies nowadays, and while I will not say that it's Luhrmann's fault that I have since moved on to things like The Fall and Italian horror, I will also say that the exact nature of my enthusiasm for Moulin Rouge! is not so very different at all from the enthusiasm I hold for The Beyond.

Actually, I should refine what I've just said: it's not that the story of MR is a hatchet job, or anything; it's just very, very, very hackneyed, in ways that the script by Luhrmann and Craig Pearce takes great joy in pointing out - pretty much every beat in the "real" story also takes place in a stage musical being written by the characters, and we're meant to understand, I think, that this musical is a bit trite and overplayed, if extremely sincere. Besides the which, it's not like the writers are exactly hiding the fact that they're stealing almost everything from the operas La traviata and La bohème (Luhrmann directed a production of the latter shortly after the film's opening), and the Greek myth of Orpheus. And it's not true that the story is totally immaterial: it provides the framework for everything else to do what it does, and perhaps the real lesson of Moulin Rouge! is not that story doesn't matter if the style is right, but that the way a story is told can be far more important than the actual details of the story. For if the tale told here of an aspiring, bohemian writer named Christian (Ewan MacGregor) and a gorgeous, consumption-ridden courtesan named Satine (Nicole Kidman) is musty to the point of outright hilarity, the emotions that Luhrmann explores through it are true enough, and the method through which he explores them downright revelatory - while I, like many formerly youthful cinephiles, have learned to my dismay that many of the films I used to think were amazing turn out to be barely-hidden riffs on older movies, I've still not stumbled upon a precursor for this movie, which has not a single original idea to its name on any level, but combines those ideas in a shape previously unknown, and unseen since.

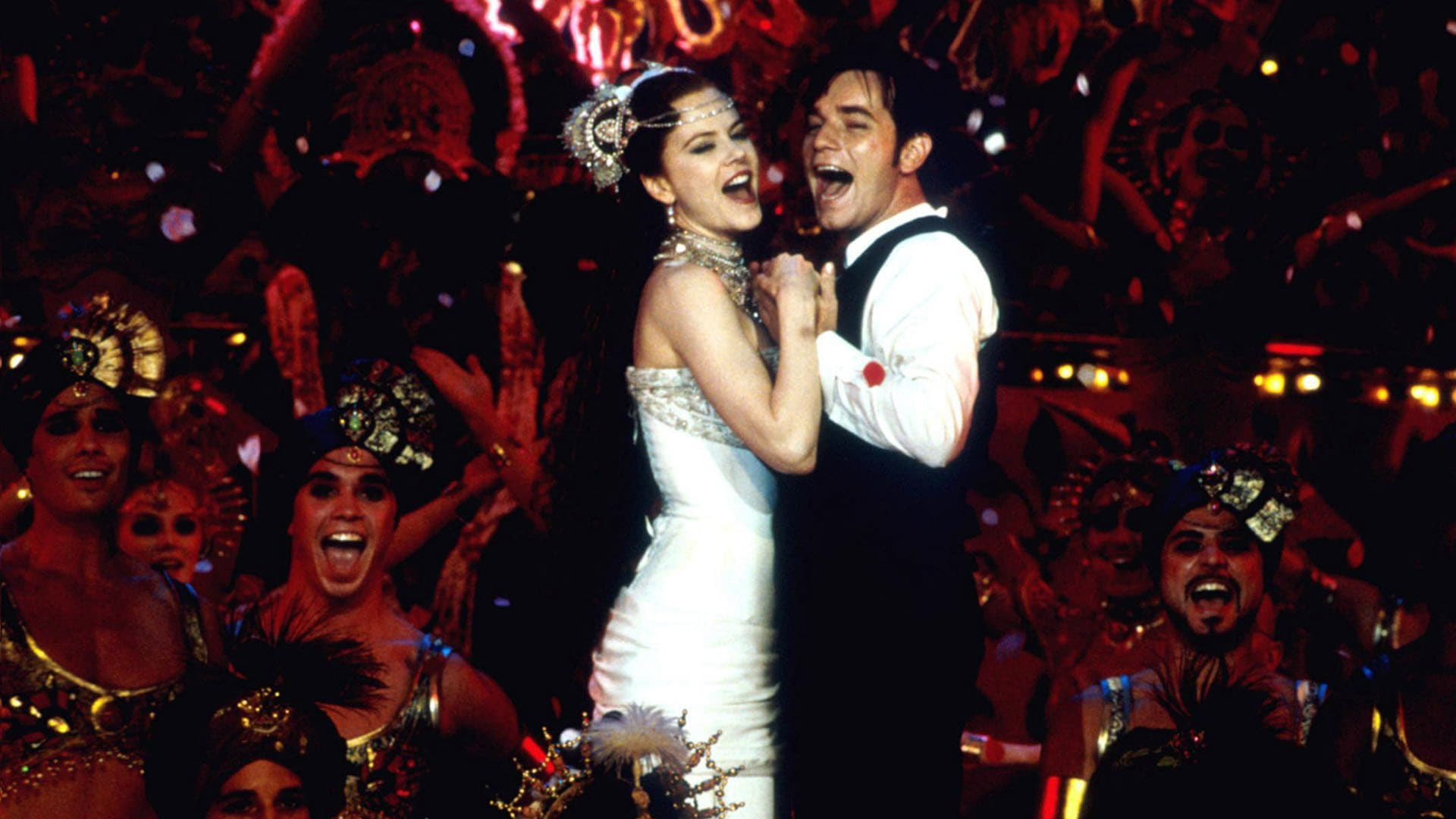

"Above all, this is a story about love" - but it is also a story about the death of innocence, and the discovery that beauty and agony can come from the same place. What the film does best is to depict this arc, married to the arc of falling in love for the first time and finding it overwhelming, through entirely visual means, having stated at the outset, "this, by the way, is the theme you are looking for". It's not a subtle or restrained movie in any regard whatsoever: almost bullying, in fact, though I prefer to think of it in the terms laid out within the film by nightclub impresario Harold Zidler (Jim Broadbent): "A magnificent, opulent, tremendous, stupendous, gargantuan, bedazzlement, a sensual ravishment." My word, yes, one's senses do get quite ravished by Moulin Rouge!, particularly whichever sense is responsible for paying attention during quickly-edited scenes, of which there is no other kind in this film. Even in an era where shot lengths have been shortening precipitously, the film remains singularly fast-pitched; but even so recently as 2001, films this hectic were virtually unheard of, and the film felt somewhat like sitting at the heart of a neutron bomb explosion.

The point - for that's what makes Jill Bilcock's editing special, that there actually is a point, and not just chaos for the sake of it like the dozens of contemporary movies with cuts set to the rhythm of Hell's Geiger counter - is that the feverish editing is meant to create in the viewer the experience of being the protagonist: this is nowhere clearer than in the opening ten minutes, which go from a haunting, dissolve-heavy montage of inchoate images (which we'll eventually learn represents Christian's free association of thoughts from a period one year later than the main part of the film), settling on the young hero writing down the great tragic love story that happened on his arrival in Paris in 1899, and it's all subdued and abstractly shot; and then, when we fully commit to the flashback, the movie jolts along so psychotically that it's terrifying if not out-and-out unpleasant to watch: 1900-Christian's narration shifts tones almost by the word as 1899-Christian meets a whole garret full of weird characters, who rope him into helping compose their new bohemian revolutionary musical for which he supplies the key line, "The hills are alive with the sound of music." Things are thrown at us fast in this sequence, and the cinematography is so distorted as to seem grotesque; even a familiarity with the film that, itself, borders on the grotesque hasn't managed to immunize me against how damn giddy those first ten minutes are, and I think this is a deliberate gambit: Luhrmann and Bilcock and DP Donald McAlpine are throwing us right into the deep end, sort of the "weed-out" part of the movie: if you can keep up with whatever the hell is going on here, you'll be fine for the rest of it.

Not that it's that hard to parse, just that it's incredibly aggressive. But straightforward enough: Christian is caught off guard by a dazzling, strange world, and so the viewer, by means of the editing, is caught off guard the same way; just like, later on in the film, editing is used to whip the viewer back and forth in a cinematic replication of the sensation of dance, rather than the look of dance (for, as needs hardly be said, a movie with this kind of machine-gun editing isn't really equipped to give us a good look at its dancers, though in at least one number, "El Tango de Roxanne", the quick cutting does a good job of drawing our attention to the dancer's individual movements, if not the flow between movements).

That kind of pure experiential way of appreciating the film has always been my favorite thing about it; but in the manner of all truly great art, there are plenty of ways into Moulin Rouge!: its appropriation of cinematic history is a good one, with references to everything from Georges Méliès to Jane Campion, and especially Hollywood musicals of the '40s and '50s, whose florid full-color excess is recreated with considerable ebullience by Luhrmann and McAlpine, and even moreso by Lurhmann's wife Catherine Martin on production and costume design detail (the latter credit shared with Angus Strathie). It's a movie high on spectacle - there is a song, "The Pitch (Spectacular Spectacular)" that could double as Luhrmann's manifesto to create something unimaginably big and imaginative and gaudy and delightful - and the spectacle is well and truly good.

It's also genuinely warm and human, with a whole mess of strong performances in the middle of it: Kidman is the obvious best in show, doing remarkably shaded work as a woman with layers upon layers, to the point that she's just about lost track of where the real center is, with a number of small moments, tossed-off asides really, where Satine-the-actress stops playing for just a second when nobody is watching. Almost as good is Broadbent's broad, genial Zidler, a buffoonish showman with a deep, hidden paternal streak, and the shift from one to other is exactly tailored to his best strengths as a performer. If nobody else is at that level - MacGregor is a bit too callow, Richard Roxburgh as the antagonistic Duke and John Leguizamo as Toulouse-Lautrec hanging to one note each (though it's hard to imagine, particularly in Roxburgh's case, that more depth would have done much good) - it's not a slam on them or the film; and the human element extends to the singing, which never feels quite professional, but this only adds to the film's charm, I find, that the characters thus feel more like people.

And with the music all consisting of rejiggered pop songs, there's less distinction between great and adequate singing anyway; for Moulin Rouge! is, after all, a jukebox musical, consisting of a slurry of various eras and styles covered in all sorts of styles (a comic opera "Like a Virgin", a tango "Roxanne"). There's a danger in attempting a jukebox musical; there are so very many ways for them to go bad. But Moulin Rouge! is so conceptually self-assured that it works as well here as I think it ever has, for this was not Luhrmann's first time at something like this; the film is the third in a loosely-defined "Red Curtain Trilogy", in which the director uses conscious artifice to separate us out from the reality of the film, and then uses a specific gimmick to draw us back in at a heightened level - mechanically deconstructed dancing in Strictly Ballroom, distractingly modern-dress Shakespeare in William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet, and unexpected reconfigurations of familiar songs in this, by far the most successful and sustained of the three. By taking us outside of the story - which, again is not just dumb cliché, but willfully and pointedly so - and allowing us to watch the characters' emotions from outside, and then using the gimmick to dislodge us and pull us back in (it's this that he does much better in Moulin Rouge! than the others - Romeo + Juliet in particular never stops feeling distant and alienated) so that we can re-experience those emotions from a different point "inside" the material. It's a way of contemplating what the movie depicts and feeling it at the same time, a detached immersion of sorts. And Luhrmann makes this all happen inside a movie that is filled with wall-to-wall eye and ear candy, so the more subtle abstractions happen almost without our paying attention to them, since so much is going on to distract us from the games he's playing with our identification with the characters.

Sensual ravishment, indeed. And so delighting that I suspect it shall in fact still be here in fifty years, if never a widely-regarded classic, than still the object of intense, cultish devotion that it has enjoyed for eleven years that haven't caused the movie to age a day.

But the point is, I saw Moulin Rouge! (the punctuation is important for two reasons: to emphasise the film's non-stop madcap pace, and to distinguish it from John Huston's soporific Moulin Rouge of 1952) under circumstances that remain particularly memorable to me - it was the first time I'd ever really spent time with a now very dear friend, and the walk back from the movie theater included the first conversation I ever had about what special features I expected to show up on the future DVD (which, in the event, was a particularly well-stocked one; and, better yet, came out on my 20th birthday, which I took to be a good omen) - and it taught me the single most important lesson that I could have ever learned on the way to becoming the particular sort of cinephile I am today: that there could be a movie I loved for its energy, its color and lushness, its performances, its visual sense of humor, its manic editing, its commitment to bringing the long-dead musical genre back to life in a vigorously contemporary idiom without feeling hollow and hip - that there could be a movie that would so thoroughly delight me that even today, it's intractably on my Desert Island Top 10. And that it could be all of this despite possessing an unbelievably dumb script. And, in fairness, a purposefully unbelievably dumb script, but the fact remains that nobody could get away with calling Moulin Rouge! a triumph of screenwriting. This sudden, shocked understanding that I could - and did! - adore a film for reasons that had nothing at all to do with its narrative underlies pretty much all of the feelings I have towards movies nowadays, and while I will not say that it's Luhrmann's fault that I have since moved on to things like The Fall and Italian horror, I will also say that the exact nature of my enthusiasm for Moulin Rouge! is not so very different at all from the enthusiasm I hold for The Beyond.

Actually, I should refine what I've just said: it's not that the story of MR is a hatchet job, or anything; it's just very, very, very hackneyed, in ways that the script by Luhrmann and Craig Pearce takes great joy in pointing out - pretty much every beat in the "real" story also takes place in a stage musical being written by the characters, and we're meant to understand, I think, that this musical is a bit trite and overplayed, if extremely sincere. Besides the which, it's not like the writers are exactly hiding the fact that they're stealing almost everything from the operas La traviata and La bohème (Luhrmann directed a production of the latter shortly after the film's opening), and the Greek myth of Orpheus. And it's not true that the story is totally immaterial: it provides the framework for everything else to do what it does, and perhaps the real lesson of Moulin Rouge! is not that story doesn't matter if the style is right, but that the way a story is told can be far more important than the actual details of the story. For if the tale told here of an aspiring, bohemian writer named Christian (Ewan MacGregor) and a gorgeous, consumption-ridden courtesan named Satine (Nicole Kidman) is musty to the point of outright hilarity, the emotions that Luhrmann explores through it are true enough, and the method through which he explores them downright revelatory - while I, like many formerly youthful cinephiles, have learned to my dismay that many of the films I used to think were amazing turn out to be barely-hidden riffs on older movies, I've still not stumbled upon a precursor for this movie, which has not a single original idea to its name on any level, but combines those ideas in a shape previously unknown, and unseen since.

"Above all, this is a story about love" - but it is also a story about the death of innocence, and the discovery that beauty and agony can come from the same place. What the film does best is to depict this arc, married to the arc of falling in love for the first time and finding it overwhelming, through entirely visual means, having stated at the outset, "this, by the way, is the theme you are looking for". It's not a subtle or restrained movie in any regard whatsoever: almost bullying, in fact, though I prefer to think of it in the terms laid out within the film by nightclub impresario Harold Zidler (Jim Broadbent): "A magnificent, opulent, tremendous, stupendous, gargantuan, bedazzlement, a sensual ravishment." My word, yes, one's senses do get quite ravished by Moulin Rouge!, particularly whichever sense is responsible for paying attention during quickly-edited scenes, of which there is no other kind in this film. Even in an era where shot lengths have been shortening precipitously, the film remains singularly fast-pitched; but even so recently as 2001, films this hectic were virtually unheard of, and the film felt somewhat like sitting at the heart of a neutron bomb explosion.

The point - for that's what makes Jill Bilcock's editing special, that there actually is a point, and not just chaos for the sake of it like the dozens of contemporary movies with cuts set to the rhythm of Hell's Geiger counter - is that the feverish editing is meant to create in the viewer the experience of being the protagonist: this is nowhere clearer than in the opening ten minutes, which go from a haunting, dissolve-heavy montage of inchoate images (which we'll eventually learn represents Christian's free association of thoughts from a period one year later than the main part of the film), settling on the young hero writing down the great tragic love story that happened on his arrival in Paris in 1899, and it's all subdued and abstractly shot; and then, when we fully commit to the flashback, the movie jolts along so psychotically that it's terrifying if not out-and-out unpleasant to watch: 1900-Christian's narration shifts tones almost by the word as 1899-Christian meets a whole garret full of weird characters, who rope him into helping compose their new bohemian revolutionary musical for which he supplies the key line, "The hills are alive with the sound of music." Things are thrown at us fast in this sequence, and the cinematography is so distorted as to seem grotesque; even a familiarity with the film that, itself, borders on the grotesque hasn't managed to immunize me against how damn giddy those first ten minutes are, and I think this is a deliberate gambit: Luhrmann and Bilcock and DP Donald McAlpine are throwing us right into the deep end, sort of the "weed-out" part of the movie: if you can keep up with whatever the hell is going on here, you'll be fine for the rest of it.

Not that it's that hard to parse, just that it's incredibly aggressive. But straightforward enough: Christian is caught off guard by a dazzling, strange world, and so the viewer, by means of the editing, is caught off guard the same way; just like, later on in the film, editing is used to whip the viewer back and forth in a cinematic replication of the sensation of dance, rather than the look of dance (for, as needs hardly be said, a movie with this kind of machine-gun editing isn't really equipped to give us a good look at its dancers, though in at least one number, "El Tango de Roxanne", the quick cutting does a good job of drawing our attention to the dancer's individual movements, if not the flow between movements).

That kind of pure experiential way of appreciating the film has always been my favorite thing about it; but in the manner of all truly great art, there are plenty of ways into Moulin Rouge!: its appropriation of cinematic history is a good one, with references to everything from Georges Méliès to Jane Campion, and especially Hollywood musicals of the '40s and '50s, whose florid full-color excess is recreated with considerable ebullience by Luhrmann and McAlpine, and even moreso by Lurhmann's wife Catherine Martin on production and costume design detail (the latter credit shared with Angus Strathie). It's a movie high on spectacle - there is a song, "The Pitch (Spectacular Spectacular)" that could double as Luhrmann's manifesto to create something unimaginably big and imaginative and gaudy and delightful - and the spectacle is well and truly good.

It's also genuinely warm and human, with a whole mess of strong performances in the middle of it: Kidman is the obvious best in show, doing remarkably shaded work as a woman with layers upon layers, to the point that she's just about lost track of where the real center is, with a number of small moments, tossed-off asides really, where Satine-the-actress stops playing for just a second when nobody is watching. Almost as good is Broadbent's broad, genial Zidler, a buffoonish showman with a deep, hidden paternal streak, and the shift from one to other is exactly tailored to his best strengths as a performer. If nobody else is at that level - MacGregor is a bit too callow, Richard Roxburgh as the antagonistic Duke and John Leguizamo as Toulouse-Lautrec hanging to one note each (though it's hard to imagine, particularly in Roxburgh's case, that more depth would have done much good) - it's not a slam on them or the film; and the human element extends to the singing, which never feels quite professional, but this only adds to the film's charm, I find, that the characters thus feel more like people.

And with the music all consisting of rejiggered pop songs, there's less distinction between great and adequate singing anyway; for Moulin Rouge! is, after all, a jukebox musical, consisting of a slurry of various eras and styles covered in all sorts of styles (a comic opera "Like a Virgin", a tango "Roxanne"). There's a danger in attempting a jukebox musical; there are so very many ways for them to go bad. But Moulin Rouge! is so conceptually self-assured that it works as well here as I think it ever has, for this was not Luhrmann's first time at something like this; the film is the third in a loosely-defined "Red Curtain Trilogy", in which the director uses conscious artifice to separate us out from the reality of the film, and then uses a specific gimmick to draw us back in at a heightened level - mechanically deconstructed dancing in Strictly Ballroom, distractingly modern-dress Shakespeare in William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet, and unexpected reconfigurations of familiar songs in this, by far the most successful and sustained of the three. By taking us outside of the story - which, again is not just dumb cliché, but willfully and pointedly so - and allowing us to watch the characters' emotions from outside, and then using the gimmick to dislodge us and pull us back in (it's this that he does much better in Moulin Rouge! than the others - Romeo + Juliet in particular never stops feeling distant and alienated) so that we can re-experience those emotions from a different point "inside" the material. It's a way of contemplating what the movie depicts and feeling it at the same time, a detached immersion of sorts. And Luhrmann makes this all happen inside a movie that is filled with wall-to-wall eye and ear candy, so the more subtle abstractions happen almost without our paying attention to them, since so much is going on to distract us from the games he's playing with our identification with the characters.

Sensual ravishment, indeed. And so delighting that I suspect it shall in fact still be here in fifty years, if never a widely-regarded classic, than still the object of intense, cultish devotion that it has enjoyed for eleven years that haven't caused the movie to age a day.