Star child

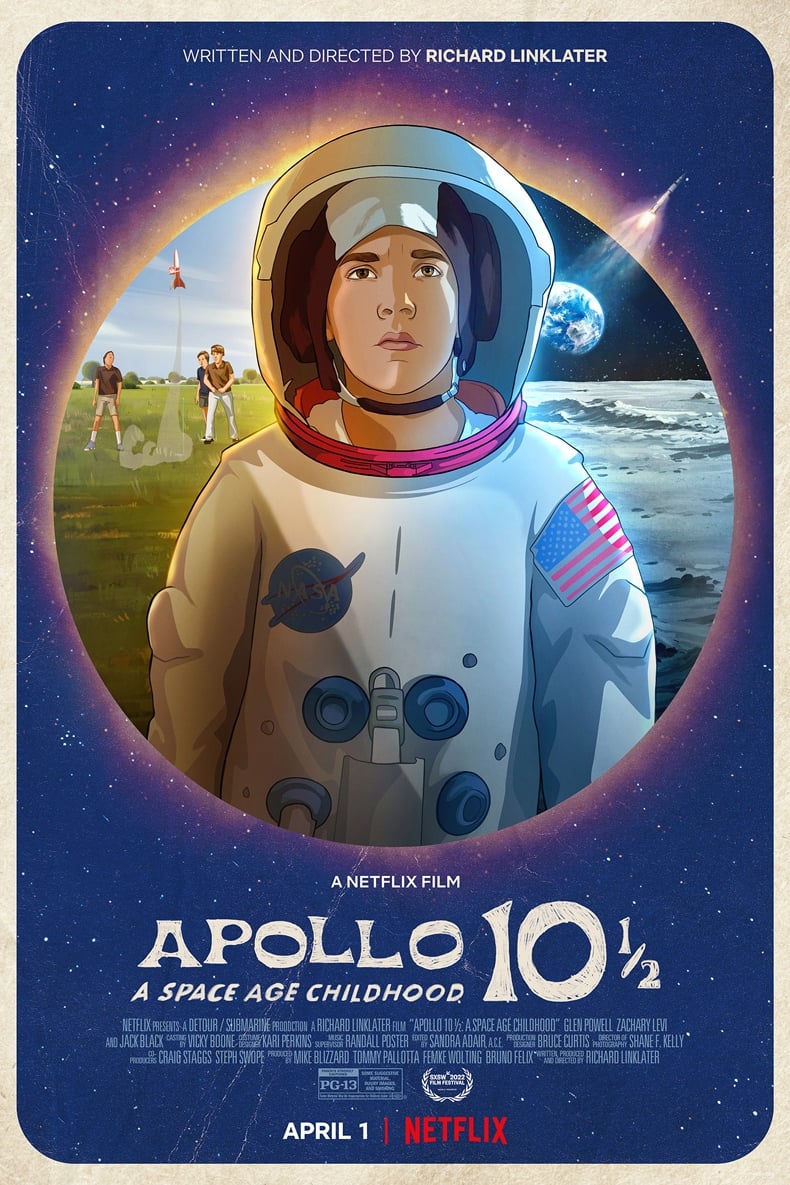

The genre in which the intermittently great American filmmaker Richard Linklater most consistently demonstrates his greatness (outside of "Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke walk around a city having epistemological debates") must surely be "Richard Linklater revisits a very particular slice of Richard Linklater's own life". And as far as that goes, he's perhaps never gone so very hard into doing that specific thing as he does with Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, which represents one of the rare and precious times that Netflix throwing money at a filmmaker has resulted in an immediate and unmistakable upswing in the quality of their work. For Linklater was in desperate need of a little, scruffy, personal one: his last film was Where'd You Go, Bernadette in 2019, and his last film before that was Last Flag Flying in 2017, and that wasn't a good place for him to be at all. We get that, with Linklater; a couple two, three good or very good or downright great movies in a row, and then he suddenly collapses into a pool of ugly quasi-Oscarbait that's terrible at it, and feels like what somebody who doesn't ever actually watch literary adaptations think that literary adaptations look like. And then he rights himself.

Apollo 10½, to be clear, doesn't find Linklater righting himself with anything like the serene confidence he did with Bernie in 2012, the last time he had to play that trick (that one was coming off the one-two-three punch of Bad News Bears in 2005, Fast Food Nation in 2006, and Me and Orson Welles in 2008 - a uniquely dire stretch, even allowing that 2006's A Scanner Darkly means that it wasn't precisely three consecutive films; still; I think there's a fair argument that any one of those three could be called the director's worst feature). It is such a dreamy swim through nostalgia for a specific time at a specific place that it somewhat forgets to have any kind of structure at all. And Linklater's films typically do better without too much structure, but this takes that to some previously unexplored extreme, where time passes without marking itself, emotional states replace each other without warning, and the subplot that gives the film its title keeps flicking on and off at random intervals, and never takes place chronologically with the rest.

That subplot is also pretty handily the worst thing about the film, or at any rate the least successful. Stan (Milo Coy), a Houston boy of around 8 or 9 in the summer of 1969 (we only know for sure that he was born in the '60s; Linklater himself turned 9 on 30 July of that year), is visited by two men from NASA, Kranz (Zachary Levi) and Bostick (Glen Powell), who are embarrassed to admit that they built the Apollo capsule too small for an adult, but they think a smart, brave boy like Stan would fit into it pretty well, and giving the mission the nickname Apollo 10½, they plan to secretly put him into space ahead of the Apollo 11 flight, just to avoid falling behind in the space race against the Soviet Union. And right when he gets into basic training, the older version of Stan doing all the narrating (Jack Black) decides that we've gotten ahead of ourselves, and and he'd best give us some context of life in Houston during the latter half of the 1960s, with a dad who was himself a NASA functionary. What it was like to have a space age childhood, if you will.

The Apollo 10½ never, ever gels: clearly, we understand it must be some manner of fantasy, whether Stan's or adult Stan's, but the movie Apollo 10½ doesn't have the heightened energy or comic tone that would sell that. So after it reappears, midway through the 97-minute film, the basic training and spaceflight subplot just kind of slots into the same dreamy diffusion of things clearly marked out as real, and things marked out as filtered through a thick lens of mostly uncritical nostalgia; adult Stan's or Linklater's, it's hard to say, and at any rate Stan clearly isn't exactly Linklater the child. But the movie clearly comes from Linklater's childhood memories, which clearly make him very happy, and which remain precise and unerringly detailed in all of the textures, designs, and the general mood of the world in those heady days to be a young middle class American boy. All of which is terrifically watchable, but that's a different point than the one I was making, which is that the fantasy Apollo 10½ cutaways just don't play, and they add a lot of clutter to a film that does start to lose its way right around that same midway point.

Basically, there are three tendrils here: the Apollo 10½ material, the broader material about being simultaneously excited for the impending moon landing and then somewhat bored by how much of the actual mission consisted of stentorian men on the news talking about things we can't see, and the broadest material about just what it was like to be alive in the 1960s, with the society-wide fascination with Space Age and Atomic Age cultural trappings and the last lingering vestiges of mid-century modern design adding just a little elegant class to the bright kitsch of it all. This broadest material, which dominates the first half and continues to put in appearances thereafter, is by far my favorite aspect of Apollo 10½, not least because it's where Linklater seems the least trapped inside his own head, and best able to get at the spirit of a historical time in the way that makes 1993's Dazed and Confused remain one of the very best films of his entire career. It's still very much the Space Age "as seen by a child", not an objective, god's-eye-view attempt to bring the period to life, but this approach works extremely well. The live-action footage has been entirely covered by a digital paint job akin to the one used for Linklater's 2001 Waking Life and 2006 A Scanner Darkly: ambition-wise, this one probably falls in-between those two, with some feints towards a wide range of styles, and even the illusion of multimedia animation in the early going. But this doesn't keep up; the film has one style that it mostly focuses on, and that style gives the film a bright, flat sheen of solid colors that pull it just a little bit out of reality, and yoke it tightly to the perspective of a child whose media diet includes enough animation that thinking of the world as "animated" comes naturally to him (and I'm not going to make a big thing about whether "rotoscoping" technically counts as "animation", or whether what we see in this film is "rotoscoping" in any meaningful sense, but I am going to leave an unnecessarily wordy parenthetical here to gum up the flow of the review and make sure you're all thinking about it). To Stan, as presumably to young Linklater, as to I'm sure others of us in our childhoods, the world is kind of a cartoon place, might as well give it a cartoon veneer.

It's a perfect visual match to the warm nostalgia of the storytelling and the slight lilt of knowing, detached sophistication that Black brings to his voiceover narration (the film is never quite "critical" of Stan's childhood perspective of the adult world, but Black at least makes sure that adult Stan isn't just romanticising boyish innocence). The film's attitude strikes a between "the cultural trappings of the Space Age were so neat" and "the cultural trappings of the Space Age were so silly", and it obviously doesn't believe for an instant that these are irreconcilable positions. Painting the images in smooth digital colors helps to sell that mixed tone, given that animation is routinely something that is both neat and silly (this gets an especially engaging workout when Stand discovers 2001: A Space Odyssey, which is made to look handsomely odd thanks to the application of the same digital ink and paint). It allows the film to present several vignettes of childhood in midcentury suburban Texas as a mixture of the dreamy, diaristic mode of e.g. The Tree of Life (not at all a comparison that favors Apollo 10½, but I kept coming back to it) and the inherent detachment provided by the the aesthetic, consigning all of this firmly to the realm of "anyway, that's all done now". Those vignettes are all over the place: some as brief as one shot, some a few moments long, some stretched into full-on anecdotes (the recreation of Houston's long-gone Astroworld theme park and its iconic Alpine Sleighs ride is particularly lively and attentive). Some are affectionate portraits of the strong bonds of love inside a family, some are more ambivalent about the tensions that come from two adults and six children living under one roof; some present childhood as a time of wonderful discovery, some present it as a source of unreflective pettiness and even cruelty. All of these are treated by the director with his characteristic candor, attentive observation, and a complete lack of judgment or moralizing.

This is all marvelous and sweet-natured, but at a certain point it becomes clear that we're not going to get any more than that. I don't know that we need any more; Linklater's films are always about that calm, generous mood - he is, I think, English-language cinema's all-time best "hang-out movie" director, and Apollo 10½ is about nothing if it's not about hanging out. But sometimes, like in Dazed and Confused, the hanging out is combined with a keen sense of what it means to be part of the messiness of humanity. Apollo 10½, ultimately, feels like it's mostly about what it means to be 9-year-old Richard Linklater. God knows, no artist owes us anything more than honesty, and this is an achingly honest film; I wish it had more oomph to it, is all.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Apollo 10½, to be clear, doesn't find Linklater righting himself with anything like the serene confidence he did with Bernie in 2012, the last time he had to play that trick (that one was coming off the one-two-three punch of Bad News Bears in 2005, Fast Food Nation in 2006, and Me and Orson Welles in 2008 - a uniquely dire stretch, even allowing that 2006's A Scanner Darkly means that it wasn't precisely three consecutive films; still; I think there's a fair argument that any one of those three could be called the director's worst feature). It is such a dreamy swim through nostalgia for a specific time at a specific place that it somewhat forgets to have any kind of structure at all. And Linklater's films typically do better without too much structure, but this takes that to some previously unexplored extreme, where time passes without marking itself, emotional states replace each other without warning, and the subplot that gives the film its title keeps flicking on and off at random intervals, and never takes place chronologically with the rest.

That subplot is also pretty handily the worst thing about the film, or at any rate the least successful. Stan (Milo Coy), a Houston boy of around 8 or 9 in the summer of 1969 (we only know for sure that he was born in the '60s; Linklater himself turned 9 on 30 July of that year), is visited by two men from NASA, Kranz (Zachary Levi) and Bostick (Glen Powell), who are embarrassed to admit that they built the Apollo capsule too small for an adult, but they think a smart, brave boy like Stan would fit into it pretty well, and giving the mission the nickname Apollo 10½, they plan to secretly put him into space ahead of the Apollo 11 flight, just to avoid falling behind in the space race against the Soviet Union. And right when he gets into basic training, the older version of Stan doing all the narrating (Jack Black) decides that we've gotten ahead of ourselves, and and he'd best give us some context of life in Houston during the latter half of the 1960s, with a dad who was himself a NASA functionary. What it was like to have a space age childhood, if you will.

The Apollo 10½ never, ever gels: clearly, we understand it must be some manner of fantasy, whether Stan's or adult Stan's, but the movie Apollo 10½ doesn't have the heightened energy or comic tone that would sell that. So after it reappears, midway through the 97-minute film, the basic training and spaceflight subplot just kind of slots into the same dreamy diffusion of things clearly marked out as real, and things marked out as filtered through a thick lens of mostly uncritical nostalgia; adult Stan's or Linklater's, it's hard to say, and at any rate Stan clearly isn't exactly Linklater the child. But the movie clearly comes from Linklater's childhood memories, which clearly make him very happy, and which remain precise and unerringly detailed in all of the textures, designs, and the general mood of the world in those heady days to be a young middle class American boy. All of which is terrifically watchable, but that's a different point than the one I was making, which is that the fantasy Apollo 10½ cutaways just don't play, and they add a lot of clutter to a film that does start to lose its way right around that same midway point.

Basically, there are three tendrils here: the Apollo 10½ material, the broader material about being simultaneously excited for the impending moon landing and then somewhat bored by how much of the actual mission consisted of stentorian men on the news talking about things we can't see, and the broadest material about just what it was like to be alive in the 1960s, with the society-wide fascination with Space Age and Atomic Age cultural trappings and the last lingering vestiges of mid-century modern design adding just a little elegant class to the bright kitsch of it all. This broadest material, which dominates the first half and continues to put in appearances thereafter, is by far my favorite aspect of Apollo 10½, not least because it's where Linklater seems the least trapped inside his own head, and best able to get at the spirit of a historical time in the way that makes 1993's Dazed and Confused remain one of the very best films of his entire career. It's still very much the Space Age "as seen by a child", not an objective, god's-eye-view attempt to bring the period to life, but this approach works extremely well. The live-action footage has been entirely covered by a digital paint job akin to the one used for Linklater's 2001 Waking Life and 2006 A Scanner Darkly: ambition-wise, this one probably falls in-between those two, with some feints towards a wide range of styles, and even the illusion of multimedia animation in the early going. But this doesn't keep up; the film has one style that it mostly focuses on, and that style gives the film a bright, flat sheen of solid colors that pull it just a little bit out of reality, and yoke it tightly to the perspective of a child whose media diet includes enough animation that thinking of the world as "animated" comes naturally to him (and I'm not going to make a big thing about whether "rotoscoping" technically counts as "animation", or whether what we see in this film is "rotoscoping" in any meaningful sense, but I am going to leave an unnecessarily wordy parenthetical here to gum up the flow of the review and make sure you're all thinking about it). To Stan, as presumably to young Linklater, as to I'm sure others of us in our childhoods, the world is kind of a cartoon place, might as well give it a cartoon veneer.

It's a perfect visual match to the warm nostalgia of the storytelling and the slight lilt of knowing, detached sophistication that Black brings to his voiceover narration (the film is never quite "critical" of Stan's childhood perspective of the adult world, but Black at least makes sure that adult Stan isn't just romanticising boyish innocence). The film's attitude strikes a between "the cultural trappings of the Space Age were so neat" and "the cultural trappings of the Space Age were so silly", and it obviously doesn't believe for an instant that these are irreconcilable positions. Painting the images in smooth digital colors helps to sell that mixed tone, given that animation is routinely something that is both neat and silly (this gets an especially engaging workout when Stand discovers 2001: A Space Odyssey, which is made to look handsomely odd thanks to the application of the same digital ink and paint). It allows the film to present several vignettes of childhood in midcentury suburban Texas as a mixture of the dreamy, diaristic mode of e.g. The Tree of Life (not at all a comparison that favors Apollo 10½, but I kept coming back to it) and the inherent detachment provided by the the aesthetic, consigning all of this firmly to the realm of "anyway, that's all done now". Those vignettes are all over the place: some as brief as one shot, some a few moments long, some stretched into full-on anecdotes (the recreation of Houston's long-gone Astroworld theme park and its iconic Alpine Sleighs ride is particularly lively and attentive). Some are affectionate portraits of the strong bonds of love inside a family, some are more ambivalent about the tensions that come from two adults and six children living under one roof; some present childhood as a time of wonderful discovery, some present it as a source of unreflective pettiness and even cruelty. All of these are treated by the director with his characteristic candor, attentive observation, and a complete lack of judgment or moralizing.

This is all marvelous and sweet-natured, but at a certain point it becomes clear that we're not going to get any more than that. I don't know that we need any more; Linklater's films are always about that calm, generous mood - he is, I think, English-language cinema's all-time best "hang-out movie" director, and Apollo 10½ is about nothing if it's not about hanging out. But sometimes, like in Dazed and Confused, the hanging out is combined with a keen sense of what it means to be part of the messiness of humanity. Apollo 10½, ultimately, feels like it's mostly about what it means to be 9-year-old Richard Linklater. God knows, no artist owes us anything more than honesty, and this is an achingly honest film; I wish it had more oomph to it, is all.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!