Slackers in Hell

In the early 1990's, Richard Linklater wrote and directed two films - Slacker and Dazed and Confused - that were masterpieces of laid-back, plotless observation. As suggested by their titles, these are films about just kind of being; hanging around, doing nothing, and talking a lot about what's on your mind but saying very little.

Linklater's latest, the Philip K. Dick adaptation A Scanner Darkly, plays like a nightmarish looking-glass version of those films. If before, slacking was the benign and zoned-out province of kids and students, here it is the life of paranoid druggies, watching their lives and their brains slip into hell.

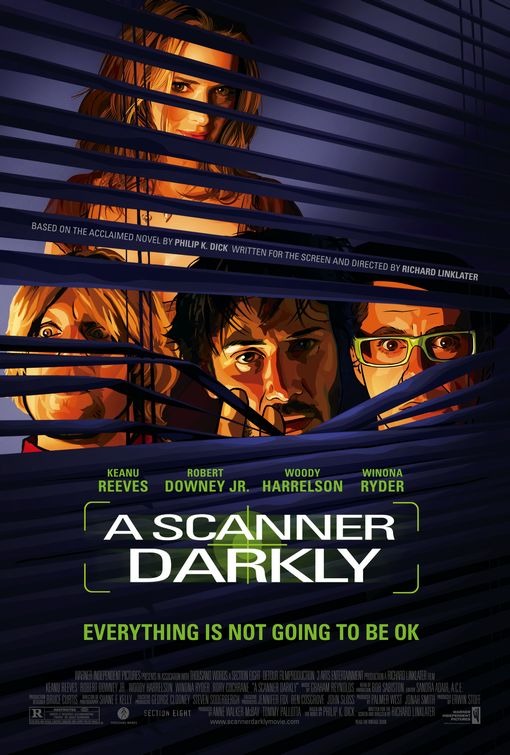

The plot: seven years from now (1994 in the 1977 novel), 20% of America is addicted to the hallucinogenic plant derivative Substance-D. Robert Arctor (Keanu Reeves) is an undercover agent assigned to infiltrate a cell of users and possible dealers - paranoid James Barris (Robert Downey, Jr.), blissed-out Ernie Luckman (Woody Harrelson) and affable but frigid Donna Hawthorne (Winona Ryder). Arctor gets himself addicted, and throughout the movie can't quite figure out who exactly he is or what's going on.

I've never read a Dick novel or story, but I've seen most of the film adaptations, and the film draws upon the usual tropes: unstable identity, inconstant memory, and technology that tends to render us weak and complacent. The rare genius of setting the story in the near future is that the gimmickry of Dick's style is stripped away and thus these tropes are all that remain. Just about the only sci-fi element of the entire plot is the "scramble suit" that Arctor wears to preserve his anonymity: a thin cloak that constantly shifts appearance, so that it's impossible to form any idea of what the wearer looks like in even a general way. It's a grand metaphor for a film whose overriding concern is the loss of self.

The first character we see to go over the bend from using Substance-D is Freck, played by Rory Cochrane. This is not the first time Cochrane has worked with Linklater; he played Slater, the chief pothead of Dazed and Confused. In that film, drugs were...not romanticized, not exactly, but treated as a mostly harmless, and Slater was played entirely for comedy. Thirteen years later, it's hard to forget that earlier role even as we see Slater/Freck descend into the heart of darkness in the very first scene. I do not claim that Linklater repudiates the earlier film; but he clearly has moved on from his onetime belief that "those were the days," and adopted a steely and even nihilistic viewpoint, that to continue living life as a slacker is to end up trapped in a filty house, convinced that aphids are crawling out of your dog. I exaggerate slightly; but as much as anything else, this is a film about abandoning youth's romanticism for a more clear-eyed, if terrifying adulthood.

(I can't claim that Dick viewed the story the same way, of course, but I wonder...the film ends with text taken from the dedication of the book, where Dick salutes all of his friends who died or were otherwise damaged during his younger days of drug use, an equally clear rejection of youthful folly).

On the subject of actors with meta-textual baggage, this film has been blessed with perhaps the most appropriate cast of any drug movie in history. Woody Harrelson is of course one of our nation's great marijuana advocates, and his character is the only one in the film who is generally joyful about his addictation, rather than psychotic. That reaction is left to Robert Downey, Jr. whose Barris is a twitching bag of insanity, almost uncomfortable to watch as his mania increases. It's one of the finest performances in any Linklater film. Keanu Reeves is a bit flat, unfortunately, the film's one serious misstep; I can understand the appeal of casting the lead from The Matrix in a Philip K. Dick story, but I was never convinced that he had much personality to lose.

Perhaps the most prominent single aspect of A Scanner Darkly is its style. It was filmed using the same interpolated rotoscoping as Linklater's Waking Life, although generally the animation is not so experimental as in that film. Many reviewers have questioned whether or not this technique was necessary, which strikes me as the wrong question: since Linklater clearly felt it was important, it falls to the audience to explore why. But I do think the technique was necessary, even vital: it gives the whole piece a sense of the uncanny, and like Waking Life the world seems to float on top of itself, like a series of plates. The result is a visceral depiction of the disorientation attendant with drug use like I've seen in no other film. It's easy to say "this character is losing his mind"; what Linklater has done is show an entire movie lose its mind. Dazed and confused, indeed.

Linklater's latest, the Philip K. Dick adaptation A Scanner Darkly, plays like a nightmarish looking-glass version of those films. If before, slacking was the benign and zoned-out province of kids and students, here it is the life of paranoid druggies, watching their lives and their brains slip into hell.

The plot: seven years from now (1994 in the 1977 novel), 20% of America is addicted to the hallucinogenic plant derivative Substance-D. Robert Arctor (Keanu Reeves) is an undercover agent assigned to infiltrate a cell of users and possible dealers - paranoid James Barris (Robert Downey, Jr.), blissed-out Ernie Luckman (Woody Harrelson) and affable but frigid Donna Hawthorne (Winona Ryder). Arctor gets himself addicted, and throughout the movie can't quite figure out who exactly he is or what's going on.

I've never read a Dick novel or story, but I've seen most of the film adaptations, and the film draws upon the usual tropes: unstable identity, inconstant memory, and technology that tends to render us weak and complacent. The rare genius of setting the story in the near future is that the gimmickry of Dick's style is stripped away and thus these tropes are all that remain. Just about the only sci-fi element of the entire plot is the "scramble suit" that Arctor wears to preserve his anonymity: a thin cloak that constantly shifts appearance, so that it's impossible to form any idea of what the wearer looks like in even a general way. It's a grand metaphor for a film whose overriding concern is the loss of self.

The first character we see to go over the bend from using Substance-D is Freck, played by Rory Cochrane. This is not the first time Cochrane has worked with Linklater; he played Slater, the chief pothead of Dazed and Confused. In that film, drugs were...not romanticized, not exactly, but treated as a mostly harmless, and Slater was played entirely for comedy. Thirteen years later, it's hard to forget that earlier role even as we see Slater/Freck descend into the heart of darkness in the very first scene. I do not claim that Linklater repudiates the earlier film; but he clearly has moved on from his onetime belief that "those were the days," and adopted a steely and even nihilistic viewpoint, that to continue living life as a slacker is to end up trapped in a filty house, convinced that aphids are crawling out of your dog. I exaggerate slightly; but as much as anything else, this is a film about abandoning youth's romanticism for a more clear-eyed, if terrifying adulthood.

(I can't claim that Dick viewed the story the same way, of course, but I wonder...the film ends with text taken from the dedication of the book, where Dick salutes all of his friends who died or were otherwise damaged during his younger days of drug use, an equally clear rejection of youthful folly).

On the subject of actors with meta-textual baggage, this film has been blessed with perhaps the most appropriate cast of any drug movie in history. Woody Harrelson is of course one of our nation's great marijuana advocates, and his character is the only one in the film who is generally joyful about his addictation, rather than psychotic. That reaction is left to Robert Downey, Jr. whose Barris is a twitching bag of insanity, almost uncomfortable to watch as his mania increases. It's one of the finest performances in any Linklater film. Keanu Reeves is a bit flat, unfortunately, the film's one serious misstep; I can understand the appeal of casting the lead from The Matrix in a Philip K. Dick story, but I was never convinced that he had much personality to lose.

Perhaps the most prominent single aspect of A Scanner Darkly is its style. It was filmed using the same interpolated rotoscoping as Linklater's Waking Life, although generally the animation is not so experimental as in that film. Many reviewers have questioned whether or not this technique was necessary, which strikes me as the wrong question: since Linklater clearly felt it was important, it falls to the audience to explore why. But I do think the technique was necessary, even vital: it gives the whole piece a sense of the uncanny, and like Waking Life the world seems to float on top of itself, like a series of plates. The result is a visceral depiction of the disorientation attendant with drug use like I've seen in no other film. It's easy to say "this character is losing his mind"; what Linklater has done is show an entire movie lose its mind. Dazed and confused, indeed.