In Heaven, everything is fine

A review requested by Michael, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

"Eraserhead is about David Lynch's terrified disgust at the thought of being a father" is such a well-worn piece of conventional wisdom that makes so much sense relative to the content of the film, I think the most important thing we can do is to immediately chuck that interpretation in the shitcan and never bring it up again. First, it's trite dimestore Freudianism, applied to a filmmaker whose work routinely seems Freudian mostly without being Freudian. Second, it requires you to ignore quite a lot of stuff, including the magnificent opening scene. Third, it gives us a handle on Eraserhead: it makes it feel like something that's been solved and can be encountered from a vantage point of relative safety and stability, since we know what it "means", and you absolutely should not ever feel like you have a handle on Eraserhead. This is a terrifying, the bottom-is-falling-out-from-beneath-us type of movie. Even with the "hatred of children" angle there to serve as our True North, the film is still pretty vertiginous in this way; it's a lot to deal with and a lot of it is confusing. But having an agreed-upon starting point at least makes us feel like there's something we can use as a foundation as we try to manage the rest of it into shape. And my argument is, we shouldn't have that foundation. We should feel horribly lost, wallowing in the film's aura of transcendent decay and wondering if we're ever going to find a way out. This isn't a Twin Peaks or a Mulholland Dr., where it feels like a puzzle inviting us to solve it (even if that feeling is an illusion). If this is a puzzle, the box it came in was all torn up, and inside there aren't even any puzzle pieces, just engorged maggots.

Plus, the narrative of Lynch's 1977 debut feature is actually very straightforward: Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) is forced into a shotgun wedding with his girlfriend Mary X (Charlotte Stewart) by her parents (Allen Joseph and Jeanne Bates), after... okay, it's not actually straightforward. Because the film puts in a particularly freaky line that makes it hard for one to just blithely say "there's a baby", and even if it's a baby, I don't know that we actually have evidence that Mary gave birth to it, nor is that claim ever made as such. But Mr. and Mrs. X operate from the principle that Mary gave birth to a baby, and while Henry seems quite certain that it's not his, they get married anyway. After living with the child for a short time - I'm about to start spoiling the movie, but you know what, you just straight-up cannot spoil a film whose interests lie as far away from narrative as Eraserhead - Mary abandons her family, since she simply cannot cope with its incessant shrill cries. Neither can Henry, and it's not much longer before he stabs the... baby... with scissors. Killing it, maybe, though "causing it to enter the next stage of its revolting alien lifecycle" could be just as likely a description of whatever it is we see.

So ambiguity, but it's not a puzzle. We know exactly what this is. It's a plunge into despair so profound it seems to infect the air. Lynch was intensely miserable when he made Eraserhead - he didn't want to be married (and in fact his wife divorced him during the film's years-long production), he didn't want to be a father, he didn't want to live in Philadelphia. Based on the evidence of the film, "he didn't want to live in Philadelphia" might have even been the most important part of that, because Eraserhead's urban environment has been grotesquely distorted through Herbert Cardwell's cinematography (he was replaced by Frederick Elmes as the production stretched on) and Lynch's own production design, until it feels hardly like a place at all, and more just a collection of expressionistic states. It's not enough to say that the city at the end of the universe where Eraserhead takes place looks "foggy". It is covered in enough smeary grain that it seems like the film stock itself is starting to dissolve into a filthy mist.

It's not sporting to play the "what future David Lynch project does this remind me of?" game, since people encountering this shockingly hazy, gorgeously repulsive object wouldn't have had that luxury, but on the other hand, Eraserhead really does feel like it contains almost everything the director would try out later on, in some form; I do not think it would be a huge exaggeration to claim that his entire subsequent career has been refining or building upon what's going on here, in some places much more plainly than others. And the two things that I am primarily thinking of right in this moment, in connection with the rotting beauty of the film's cinematography and its hollow, refuse-like art direction, are 2006's INLAND EMPIRE and Part 3 and Part 8 of the 2017 revival of Twin Peaks, which I bring up in part because the first and third items on that list are probably my two favorite things Lynch has made in all the years since Eraserhead. What these all share in common with the 1977 film is an impulse to try and warp and bend cinema not just as a visual medium, but as a recording medium, trying to make something shocking and disturbing out of the very process by which light registers photochemically on film, or has its qualities recorded by a digital sensor, as the case may be. And in that regard, I would point out that Lynch and the cinematographers, in shooting Eraserhead, have married that thick, messy grain structure with an almost wicked refusal to light scenes well, resulting in something that feels almost physically like anti-cinema - like it does not merely fail to project light, it actually pulls the light out of the space in which you're watching it. It's a choking, muddy blackness, terribly unpleasant and uncomfortable to watch.

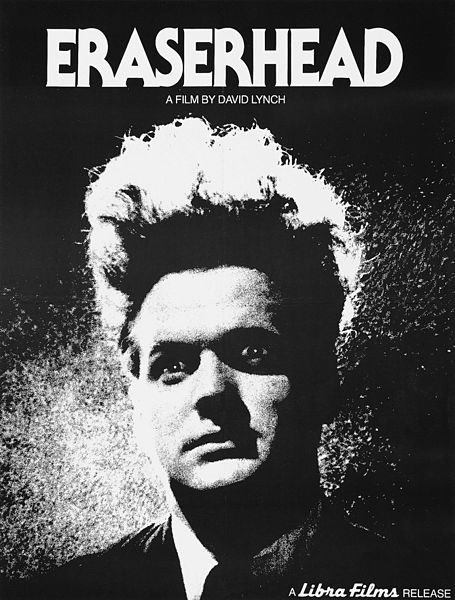

And so, back to whatever theme we want it to have: fatherhood or urban ennui or professional disappointment or just being consumed by existential depression. In any case, the film's chief approach is to make us feel as terribly uncomfortable as it possibly can. Making us feel uncomfortable would go on to become a great specialty of Lynch's; think of all those erratically flickering fluorescent lights, think of all those many, many droning hums rumbling along at the very bottom of what we can perceive on the soundtrack. He likes to make the experience of watching his films physically wearying, as a way of putting us in the off-kilter headspaces of his characters. For that matter, Eraserhead might be the most strongly empathic of his films. This has a whole lot to do with Nance's unimprovable performance as the watery-eyed everyman with a shock of Bride of Frankenstein hair who is at the centerpiece of every single scene. Nance, even more than he usually does, looks here like a cross between a surly middle-aged man and a giant baby, and he's both a grounding, expressive figure and one more uncanny visual object in a film made up of them. Either way, he has an unnerving way of pulling one in, his confused, panicked expressions providing a clear way directly into his character's constant feeling of unhappily being stuck in the wrong place with the wrong people. I genuinely don't know if we're meant to like Henry, and it couldn't possibly matter less; what the film wants for us is to be thrust into the audiovisual expression of his complete discomfort with the world around him, and it does this as well as literally any other film to have attempted this gesture that I can name.

Part of that is the imagery; more of it is the sound. If I did not otherwise already love Eraserhead, I would love it for how much attention it lavishes on the soundtrack, practically never the place that low-budget independent films spend their time and money. But this is Lynch, quite possibly the single American director of the last 50 years with the most keenly-developed understanding of how to manipulate our psychological state through auditory stimuli. And he was already there, right from the start: the throbbing hum underneath the dreamily weird opening sequence, in which Nance's head floats sideways in space, in what I can only imagine is a deliberate parody of 2001: A Space Odyssey (depending on what you make of the next few minutes, in which a man in a planet (Jack Fisk) seems to watch Henry giving birth to a wormlike creature through his silently screaming mouth, it may even in fact be a nightmare mirror version of that film's Star Baby. But I think I've probably already made it clear that I think trying to break down the symbolism in Eraserhead is a sucker's game - just let it smash into you with all its dreamy toxicity, it makes visceral sense even if it doesn't make intellectual sense). And then the hollow, cottony sounds of the city, omnipresent but distant, like the building where Henry lives is in the middle of a huge empty field ringed by factories. And the mercilessly bass drumming of rain that cuts suddenly loud in what is technically realistically motivated sound editing, but feels so hostile in the moment that seems hard to claim. And above all, in the constant squawking of the baby-thing.

Oh, yes, the baby. I've put it off because I have nothing new to say, but it's impossible to deny that the most powerful emotional punch Eraserhead can throw is built entirely around the thing that Henry and Mary raise as their child. The prop, appearing for all the world like an aborted mammal fetus about two feet in length, is an extraordinary organic construction, wet and pulsing, looking more and more necrotic as the film progresses; as far as I am aware, Lynch still hasn't told how he built it, and I wouldn't want to know. It is a magnificent, horrible object, just to look at it, the embodiment of every slimy, fleshy terror living in the most primitive part of our lizard brains, that's good enough for me. And that's when we look at it. When we hear it, it becomes that much more profoundly upsetting. Much of the sound Lynch and Alan R. Splet have cut into the soundtrack is simply the noises made by a human baby, and hearing the soft lip smacking and cowlicky twitching of an infant attached, with eerie precision, to the mouth movements of the bay - this is one of the most deeply unsettling things in all cinema, from the 1890s right to the present day. It gets at the most deeply built-in programs running in our savage ape brains, the part where we have an immediate, instinctive response to the sound of a peaceful infant of our species sleeping and mewling and complaining. And this is, in a wretchedly painful and disorienting way, not an infant. The uncanny disconnect it creates is matched by literally nothing else I can name.

So, I mean, to love Eraserhead - and I do - is to understand that it is a vicious, bleary thing. It's full of dark humor, of course: arguably, it consists solely of dark humor, and is in fact a comic parody of an inept father being smacked around by life. Plus its just 89. So it's neither a hard slog, nor necessarily an unenjoyable, unpleasant thing to sit through. But it is unrelenting, Lynch pouring everything that made him miserable and none of what made him happy into a chain of imageries that proceed with unearthly detachment from the reality of the waking world. That's another thing that first shows up here: so much imagery that feels laden with symbolic meaning while also seeming like the creation of pure, thoughtless id, wrenched out of Lynch's subconscious directly, like he was afraid it would break if he stopped to think about what it was doing. And oh, there are some wonderful dream images: a roasted chicken kicking out its legs as black viscous liquid oozes from its body; a woman living in a radiator (Laurel Near) with huge scarred cheeks constructed out of terribly unconvincing, beaming cheerily out of a cramped theatrical stage. The latter comes very along in the film, after I have started unraveling completely, and it's always been enough to finish me off: a jarring jump cut that rips us away from a close-up of that woman to a medium shot, right as she begins to sing that "In Heaven, everything is fine" with a lack of irony far more terrifying and distressing than it would have been if Lynch were being ironic. And everything about this feels so weightless, the purest version of the surreal cabarets that would follow Lynch throughout his career, just a moment of swoony bliss and beatific peace and skin-crawling horror all tied up in one.

Yes, pure. That's what I love about Eraserhead: it is Lynch's purest film. He's looking to work us over and give us lacerating emotional experience, and that's what he does, letting us get caught in a spider-web of cultural references and character psychology and unresolved questions, while the film simply rages and rages on some pre-rational level, using image and sound and rhythm as the tools for moving us to be most receptive to its vision of spiritual malaise and physical decay. It's not the first film doing this kind of thing, and thanks in part to inspiring waves of imitators, it's definitely not the last. But I am very content to call it the best.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

"Eraserhead is about David Lynch's terrified disgust at the thought of being a father" is such a well-worn piece of conventional wisdom that makes so much sense relative to the content of the film, I think the most important thing we can do is to immediately chuck that interpretation in the shitcan and never bring it up again. First, it's trite dimestore Freudianism, applied to a filmmaker whose work routinely seems Freudian mostly without being Freudian. Second, it requires you to ignore quite a lot of stuff, including the magnificent opening scene. Third, it gives us a handle on Eraserhead: it makes it feel like something that's been solved and can be encountered from a vantage point of relative safety and stability, since we know what it "means", and you absolutely should not ever feel like you have a handle on Eraserhead. This is a terrifying, the bottom-is-falling-out-from-beneath-us type of movie. Even with the "hatred of children" angle there to serve as our True North, the film is still pretty vertiginous in this way; it's a lot to deal with and a lot of it is confusing. But having an agreed-upon starting point at least makes us feel like there's something we can use as a foundation as we try to manage the rest of it into shape. And my argument is, we shouldn't have that foundation. We should feel horribly lost, wallowing in the film's aura of transcendent decay and wondering if we're ever going to find a way out. This isn't a Twin Peaks or a Mulholland Dr., where it feels like a puzzle inviting us to solve it (even if that feeling is an illusion). If this is a puzzle, the box it came in was all torn up, and inside there aren't even any puzzle pieces, just engorged maggots.

Plus, the narrative of Lynch's 1977 debut feature is actually very straightforward: Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) is forced into a shotgun wedding with his girlfriend Mary X (Charlotte Stewart) by her parents (Allen Joseph and Jeanne Bates), after... okay, it's not actually straightforward. Because the film puts in a particularly freaky line that makes it hard for one to just blithely say "there's a baby", and even if it's a baby, I don't know that we actually have evidence that Mary gave birth to it, nor is that claim ever made as such. But Mr. and Mrs. X operate from the principle that Mary gave birth to a baby, and while Henry seems quite certain that it's not his, they get married anyway. After living with the child for a short time - I'm about to start spoiling the movie, but you know what, you just straight-up cannot spoil a film whose interests lie as far away from narrative as Eraserhead - Mary abandons her family, since she simply cannot cope with its incessant shrill cries. Neither can Henry, and it's not much longer before he stabs the... baby... with scissors. Killing it, maybe, though "causing it to enter the next stage of its revolting alien lifecycle" could be just as likely a description of whatever it is we see.

So ambiguity, but it's not a puzzle. We know exactly what this is. It's a plunge into despair so profound it seems to infect the air. Lynch was intensely miserable when he made Eraserhead - he didn't want to be married (and in fact his wife divorced him during the film's years-long production), he didn't want to be a father, he didn't want to live in Philadelphia. Based on the evidence of the film, "he didn't want to live in Philadelphia" might have even been the most important part of that, because Eraserhead's urban environment has been grotesquely distorted through Herbert Cardwell's cinematography (he was replaced by Frederick Elmes as the production stretched on) and Lynch's own production design, until it feels hardly like a place at all, and more just a collection of expressionistic states. It's not enough to say that the city at the end of the universe where Eraserhead takes place looks "foggy". It is covered in enough smeary grain that it seems like the film stock itself is starting to dissolve into a filthy mist.

It's not sporting to play the "what future David Lynch project does this remind me of?" game, since people encountering this shockingly hazy, gorgeously repulsive object wouldn't have had that luxury, but on the other hand, Eraserhead really does feel like it contains almost everything the director would try out later on, in some form; I do not think it would be a huge exaggeration to claim that his entire subsequent career has been refining or building upon what's going on here, in some places much more plainly than others. And the two things that I am primarily thinking of right in this moment, in connection with the rotting beauty of the film's cinematography and its hollow, refuse-like art direction, are 2006's INLAND EMPIRE and Part 3 and Part 8 of the 2017 revival of Twin Peaks, which I bring up in part because the first and third items on that list are probably my two favorite things Lynch has made in all the years since Eraserhead. What these all share in common with the 1977 film is an impulse to try and warp and bend cinema not just as a visual medium, but as a recording medium, trying to make something shocking and disturbing out of the very process by which light registers photochemically on film, or has its qualities recorded by a digital sensor, as the case may be. And in that regard, I would point out that Lynch and the cinematographers, in shooting Eraserhead, have married that thick, messy grain structure with an almost wicked refusal to light scenes well, resulting in something that feels almost physically like anti-cinema - like it does not merely fail to project light, it actually pulls the light out of the space in which you're watching it. It's a choking, muddy blackness, terribly unpleasant and uncomfortable to watch.

And so, back to whatever theme we want it to have: fatherhood or urban ennui or professional disappointment or just being consumed by existential depression. In any case, the film's chief approach is to make us feel as terribly uncomfortable as it possibly can. Making us feel uncomfortable would go on to become a great specialty of Lynch's; think of all those erratically flickering fluorescent lights, think of all those many, many droning hums rumbling along at the very bottom of what we can perceive on the soundtrack. He likes to make the experience of watching his films physically wearying, as a way of putting us in the off-kilter headspaces of his characters. For that matter, Eraserhead might be the most strongly empathic of his films. This has a whole lot to do with Nance's unimprovable performance as the watery-eyed everyman with a shock of Bride of Frankenstein hair who is at the centerpiece of every single scene. Nance, even more than he usually does, looks here like a cross between a surly middle-aged man and a giant baby, and he's both a grounding, expressive figure and one more uncanny visual object in a film made up of them. Either way, he has an unnerving way of pulling one in, his confused, panicked expressions providing a clear way directly into his character's constant feeling of unhappily being stuck in the wrong place with the wrong people. I genuinely don't know if we're meant to like Henry, and it couldn't possibly matter less; what the film wants for us is to be thrust into the audiovisual expression of his complete discomfort with the world around him, and it does this as well as literally any other film to have attempted this gesture that I can name.

Part of that is the imagery; more of it is the sound. If I did not otherwise already love Eraserhead, I would love it for how much attention it lavishes on the soundtrack, practically never the place that low-budget independent films spend their time and money. But this is Lynch, quite possibly the single American director of the last 50 years with the most keenly-developed understanding of how to manipulate our psychological state through auditory stimuli. And he was already there, right from the start: the throbbing hum underneath the dreamily weird opening sequence, in which Nance's head floats sideways in space, in what I can only imagine is a deliberate parody of 2001: A Space Odyssey (depending on what you make of the next few minutes, in which a man in a planet (Jack Fisk) seems to watch Henry giving birth to a wormlike creature through his silently screaming mouth, it may even in fact be a nightmare mirror version of that film's Star Baby. But I think I've probably already made it clear that I think trying to break down the symbolism in Eraserhead is a sucker's game - just let it smash into you with all its dreamy toxicity, it makes visceral sense even if it doesn't make intellectual sense). And then the hollow, cottony sounds of the city, omnipresent but distant, like the building where Henry lives is in the middle of a huge empty field ringed by factories. And the mercilessly bass drumming of rain that cuts suddenly loud in what is technically realistically motivated sound editing, but feels so hostile in the moment that seems hard to claim. And above all, in the constant squawking of the baby-thing.

Oh, yes, the baby. I've put it off because I have nothing new to say, but it's impossible to deny that the most powerful emotional punch Eraserhead can throw is built entirely around the thing that Henry and Mary raise as their child. The prop, appearing for all the world like an aborted mammal fetus about two feet in length, is an extraordinary organic construction, wet and pulsing, looking more and more necrotic as the film progresses; as far as I am aware, Lynch still hasn't told how he built it, and I wouldn't want to know. It is a magnificent, horrible object, just to look at it, the embodiment of every slimy, fleshy terror living in the most primitive part of our lizard brains, that's good enough for me. And that's when we look at it. When we hear it, it becomes that much more profoundly upsetting. Much of the sound Lynch and Alan R. Splet have cut into the soundtrack is simply the noises made by a human baby, and hearing the soft lip smacking and cowlicky twitching of an infant attached, with eerie precision, to the mouth movements of the bay - this is one of the most deeply unsettling things in all cinema, from the 1890s right to the present day. It gets at the most deeply built-in programs running in our savage ape brains, the part where we have an immediate, instinctive response to the sound of a peaceful infant of our species sleeping and mewling and complaining. And this is, in a wretchedly painful and disorienting way, not an infant. The uncanny disconnect it creates is matched by literally nothing else I can name.

So, I mean, to love Eraserhead - and I do - is to understand that it is a vicious, bleary thing. It's full of dark humor, of course: arguably, it consists solely of dark humor, and is in fact a comic parody of an inept father being smacked around by life. Plus its just 89. So it's neither a hard slog, nor necessarily an unenjoyable, unpleasant thing to sit through. But it is unrelenting, Lynch pouring everything that made him miserable and none of what made him happy into a chain of imageries that proceed with unearthly detachment from the reality of the waking world. That's another thing that first shows up here: so much imagery that feels laden with symbolic meaning while also seeming like the creation of pure, thoughtless id, wrenched out of Lynch's subconscious directly, like he was afraid it would break if he stopped to think about what it was doing. And oh, there are some wonderful dream images: a roasted chicken kicking out its legs as black viscous liquid oozes from its body; a woman living in a radiator (Laurel Near) with huge scarred cheeks constructed out of terribly unconvincing, beaming cheerily out of a cramped theatrical stage. The latter comes very along in the film, after I have started unraveling completely, and it's always been enough to finish me off: a jarring jump cut that rips us away from a close-up of that woman to a medium shot, right as she begins to sing that "In Heaven, everything is fine" with a lack of irony far more terrifying and distressing than it would have been if Lynch were being ironic. And everything about this feels so weightless, the purest version of the surreal cabarets that would follow Lynch throughout his career, just a moment of swoony bliss and beatific peace and skin-crawling horror all tied up in one.

Yes, pure. That's what I love about Eraserhead: it is Lynch's purest film. He's looking to work us over and give us lacerating emotional experience, and that's what he does, letting us get caught in a spider-web of cultural references and character psychology and unresolved questions, while the film simply rages and rages on some pre-rational level, using image and sound and rhythm as the tools for moving us to be most receptive to its vision of spiritual malaise and physical decay. It's not the first film doing this kind of thing, and thanks in part to inspiring waves of imitators, it's definitely not the last. But I am very content to call it the best.