Culture of death

It's not literally the case that every single anthology film that has ever been made has one segment that threatens to seriously undo all the good work done by the rest of them, but it feels that way sometime. And There Is No Evil, the Golden Bear winner at the 2020 Berlinale, makes things extra hard on itself in that respect, at least twice over: the worst of its four segments (by a lot, and I have not yet encountered a dissenting voice on the subject) is also the last one, which hurts; it's also the longest at around 44 minutes,, which hurts even more, especially since the entire film clocks in at a prodigious 151 minutes. Do literally nothing other than go straight to the end credits after the end of the third story, and you have, in a stroke, made a much more digestible movie that's much more focused in its themes and would unhesitatingly present itself as one of the very best movies released in the United States in the first half of 2021.

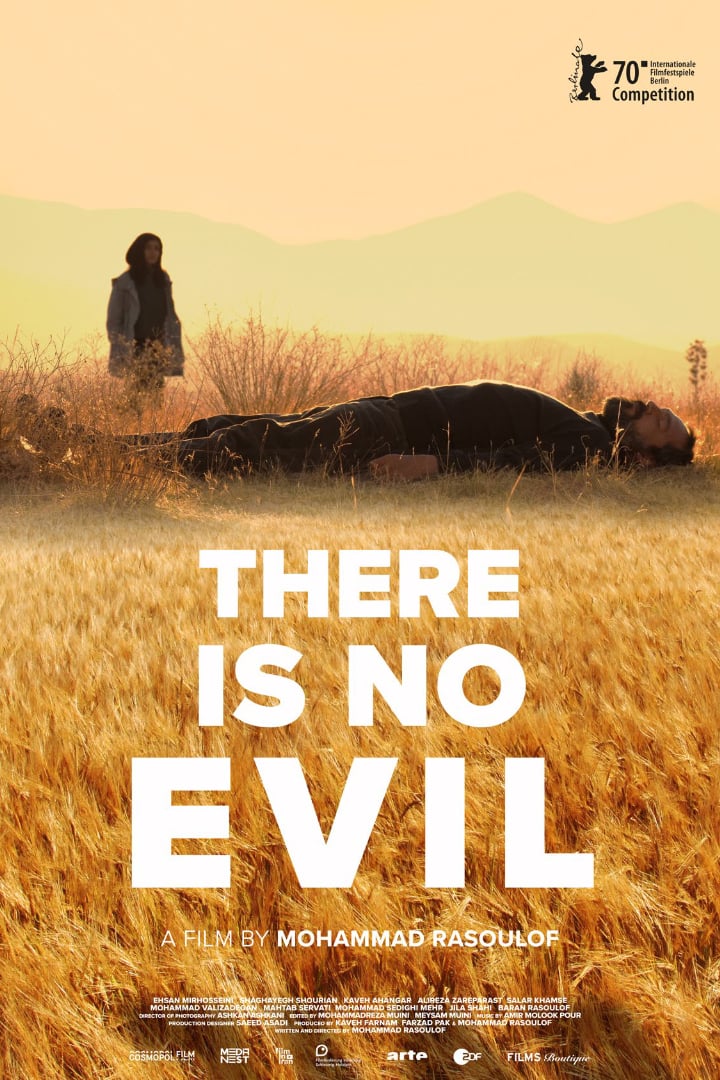

I mean, it still is that - the first half of 2021 still being in full "there's a pandemic on" crisis mode and all - and even needlessly diluting itself for so long at the end, the fundamental power of There Is No Evil is absolutely impossible to miss. The film is the newest entry in what has become a weirdly burgeoning genre of Iranian cinema, the "I am legally forbidden from making movies, but fuck you, Iranian government" film. Its writer and director, Mohammad Rasoulof, has been in more or less perpetual legal trouble since 2010 (his 2011 Cannes prizewinner Goodbye thus being one of the main sources of his troubles), but it was his 2017 A Man of Integrity that led to the hammer being brought down hard enough that he had to film his latest project in secret. And that fact alone makes There Is No Evil something of a bonafide miracle, since it absolutely does not even a little bit feel like a movie made in defiance of a ban from an authoritarian government. Unlike his countryman, colleague, and ally Jafar Panahi, who has turned every one of his own "outlaw films" (such as 2015's Taxi) into a narrative and aesthetic referendum on the ban, in essence making a series of meta-movies - they don't get much more meta than a film titled This Is Not a Film - Rasoulof is still working in broad daylight and in full view here, particularly in the first segement, and I'm not even going to try to tell you how he did it.

The four parts of There Is No Evil, a title laden with all the ambiguity and irony you'd suppose it would have to be, are all elliptically about the death penalty, but there's never in any of them a feeling of a "message" being told to us; these are all very slow-moving character studies, building up a central figure and a series of interpersonal relationships around them. Only once that work has been done, as patiently and methodically as is necessary, does Rasoulof confront us with the hard questions of how these people fit into the system of politically-sanctioned murder in Iran, to what degree they are complicit in that system and thus to what degree they are morally culpable, and what the appropriate response to that culpability might be.

The first story, also titled "There Is No Evil", is arguably the best, and certainly the hardest-hitting, though it doesn't appear that way at first. This is, in fact, the slowest-building of all four segments, possessing almost no narrative whatsoever, instead watching moments in the life of Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini), an extraordinarily anonymous middle-class man whose daily routine of struggling with little problems and sitting mostly comfortably with his family feels almost purposefully anti-cinematic; it works in that it is so aggressive in its lack of affect that the dramatic emptiness itself becomes the point, as we are confronted with the spectacle of a perfectly average man simply living his life on the screen. This all serves to set us up, or rather, to not set us up for the cut between the sequence's penultimate and final shots, when Heshmat's burning averageness is suddenly situated in the context of Iran's regime of executions, and the title goes from a curious bit of incoherent poetry to a sick, ironic twist, particularly given the exact framing of the final shot, which does not suggest that there is no evil, but that it is a desperate, horrifying need for people like Heshmat to hold up that pretense.

The second segment, "She Said, You Can Do It", is maybe even better; it relies less on the impact of a single cut, and has better acting in the form of Pouya (Kaveh Ahangar), a soldier who, as we meet him in the midst of a long, wearying debate with his comrades, is not feeling at all up to the task of executing prisoners, and has come up with a scheme that will allow him to avoid doing so. It's a glacial art film that unexpectedly and effectively turns into a lean crime thriller, and offers the closest that There Is No Evil has to some measure of optimism that people of good conscience can resist taking part in a system they despise. Though that optimism is severely tempered by the fact that Pouya still has to sacrifice elements of his life and even compromise other parts of his conscience to get to that point. The third segment, "Birthday", is a distinct touch weaker than those two, leaning hard on strained literary irony and a somewhat trite performance by Mohammad Valizadegan as a soulfully tormented hunk who wants to propose to his girlfriend (Mahtab Servati), but has chosen a uniquely inapt time to think about doing so.

"Birthday" is, however, maybe the most visually appealing slice of There Is No Evil, taking place in a wooded region that feels detached from humanity in a way that lends its story the weight of a parable, rather than the strict urban realism of the first two. What's true of all three segments, as well as the fourth, "The Kiss", is that Rasoulof and his cinematographer Askhan Ashkani have managed to focus their framing on the world around the characters - this film has a tendency to make everything feel like landscape shots, including at least some of the wider interiors - while blocking the characters within the frame so that we are keenly aware of how they fit, or don't into the world. It is a film very vividly about humans in locations, that is to say, often imprisoned even by what feel like wide open spaces with no borders in sight. They're sophisticated images by any standard, simple-looking except for the complicated, uneasy feelings they generate; that they were produced under such adverse circumstances is simply extraordinary.

That feeling, at least, persists even into "The Kiss", which is otherwise a dragged-out, redundant story about an expatriate, Darya (Baran Rasoulof, the director's daughter), who returns to Iran to visit her uncle (Mohammad Seddighimehr), now living in apparently self-imposed exile in the rural parts of the country, harboring a secret. It's a loose, puffy story, at times hard to follow, weighed down with the only trite symbolism in the movie, and far too long for what it is has to say (which is any not fresh, by this point in the film). And it is a real pity that such a thoughtful work ends up feeling like it exhausts itself and passes out rather than drawing to a pointed, powerful conclusion. Still, three out of four isn't bad, especially with the first two working so well to coldly and angrily demand that we think hard, uncomfortable thoughts about what it means to live in a repressive society and be part of it. The film's shortcomings are obvious, but so are its strengths, and the strengths simply matter so much more.

I mean, it still is that - the first half of 2021 still being in full "there's a pandemic on" crisis mode and all - and even needlessly diluting itself for so long at the end, the fundamental power of There Is No Evil is absolutely impossible to miss. The film is the newest entry in what has become a weirdly burgeoning genre of Iranian cinema, the "I am legally forbidden from making movies, but fuck you, Iranian government" film. Its writer and director, Mohammad Rasoulof, has been in more or less perpetual legal trouble since 2010 (his 2011 Cannes prizewinner Goodbye thus being one of the main sources of his troubles), but it was his 2017 A Man of Integrity that led to the hammer being brought down hard enough that he had to film his latest project in secret. And that fact alone makes There Is No Evil something of a bonafide miracle, since it absolutely does not even a little bit feel like a movie made in defiance of a ban from an authoritarian government. Unlike his countryman, colleague, and ally Jafar Panahi, who has turned every one of his own "outlaw films" (such as 2015's Taxi) into a narrative and aesthetic referendum on the ban, in essence making a series of meta-movies - they don't get much more meta than a film titled This Is Not a Film - Rasoulof is still working in broad daylight and in full view here, particularly in the first segement, and I'm not even going to try to tell you how he did it.

The four parts of There Is No Evil, a title laden with all the ambiguity and irony you'd suppose it would have to be, are all elliptically about the death penalty, but there's never in any of them a feeling of a "message" being told to us; these are all very slow-moving character studies, building up a central figure and a series of interpersonal relationships around them. Only once that work has been done, as patiently and methodically as is necessary, does Rasoulof confront us with the hard questions of how these people fit into the system of politically-sanctioned murder in Iran, to what degree they are complicit in that system and thus to what degree they are morally culpable, and what the appropriate response to that culpability might be.

The first story, also titled "There Is No Evil", is arguably the best, and certainly the hardest-hitting, though it doesn't appear that way at first. This is, in fact, the slowest-building of all four segments, possessing almost no narrative whatsoever, instead watching moments in the life of Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini), an extraordinarily anonymous middle-class man whose daily routine of struggling with little problems and sitting mostly comfortably with his family feels almost purposefully anti-cinematic; it works in that it is so aggressive in its lack of affect that the dramatic emptiness itself becomes the point, as we are confronted with the spectacle of a perfectly average man simply living his life on the screen. This all serves to set us up, or rather, to not set us up for the cut between the sequence's penultimate and final shots, when Heshmat's burning averageness is suddenly situated in the context of Iran's regime of executions, and the title goes from a curious bit of incoherent poetry to a sick, ironic twist, particularly given the exact framing of the final shot, which does not suggest that there is no evil, but that it is a desperate, horrifying need for people like Heshmat to hold up that pretense.

The second segment, "She Said, You Can Do It", is maybe even better; it relies less on the impact of a single cut, and has better acting in the form of Pouya (Kaveh Ahangar), a soldier who, as we meet him in the midst of a long, wearying debate with his comrades, is not feeling at all up to the task of executing prisoners, and has come up with a scheme that will allow him to avoid doing so. It's a glacial art film that unexpectedly and effectively turns into a lean crime thriller, and offers the closest that There Is No Evil has to some measure of optimism that people of good conscience can resist taking part in a system they despise. Though that optimism is severely tempered by the fact that Pouya still has to sacrifice elements of his life and even compromise other parts of his conscience to get to that point. The third segment, "Birthday", is a distinct touch weaker than those two, leaning hard on strained literary irony and a somewhat trite performance by Mohammad Valizadegan as a soulfully tormented hunk who wants to propose to his girlfriend (Mahtab Servati), but has chosen a uniquely inapt time to think about doing so.

"Birthday" is, however, maybe the most visually appealing slice of There Is No Evil, taking place in a wooded region that feels detached from humanity in a way that lends its story the weight of a parable, rather than the strict urban realism of the first two. What's true of all three segments, as well as the fourth, "The Kiss", is that Rasoulof and his cinematographer Askhan Ashkani have managed to focus their framing on the world around the characters - this film has a tendency to make everything feel like landscape shots, including at least some of the wider interiors - while blocking the characters within the frame so that we are keenly aware of how they fit, or don't into the world. It is a film very vividly about humans in locations, that is to say, often imprisoned even by what feel like wide open spaces with no borders in sight. They're sophisticated images by any standard, simple-looking except for the complicated, uneasy feelings they generate; that they were produced under such adverse circumstances is simply extraordinary.

That feeling, at least, persists even into "The Kiss", which is otherwise a dragged-out, redundant story about an expatriate, Darya (Baran Rasoulof, the director's daughter), who returns to Iran to visit her uncle (Mohammad Seddighimehr), now living in apparently self-imposed exile in the rural parts of the country, harboring a secret. It's a loose, puffy story, at times hard to follow, weighed down with the only trite symbolism in the movie, and far too long for what it is has to say (which is any not fresh, by this point in the film). And it is a real pity that such a thoughtful work ends up feeling like it exhausts itself and passes out rather than drawing to a pointed, powerful conclusion. Still, three out of four isn't bad, especially with the first two working so well to coldly and angrily demand that we think hard, uncomfortable thoughts about what it means to live in a repressive society and be part of it. The film's shortcomings are obvious, but so are its strengths, and the strengths simply matter so much more.