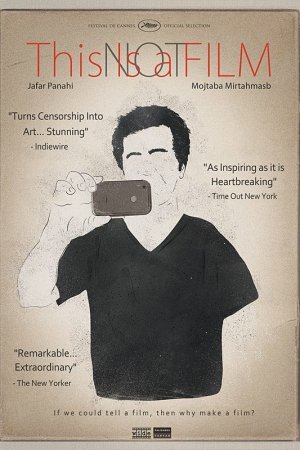

A portrait of the artist

This Is Not a Film. It is a legend passed around by cinephiles, of how Jafar Panahi, the director of several great, politically incendiary Iranian films (including The Circle and Offside), having been arrested by the government and forbidden from making any movies for 20 years, in addition to a six-year prison sentence, was able to make a documentary about his life in this period of intense pressure, smuggling it out of Iran in a USB flash drive hidden inside a cake, to play at the 2011 Cannes Festival.

This Is Not a Film. Because Panahi can't make a film, and co-conspirator Mojtaba Mirtahmasb can't help him. So if this was a film that would mean that they were breaking the law, duh.

This Is Not a Film. It's the psychoanalysis of a filmmaker,, who knows only one process by which he can absorb and discuss the world around him, and has had that taken away from him by the caprice of a terrified totalitarian government. At one point, Panahi tries to lift his spirits by remembering the project that he was developing with the officials took him into custody. With Mirtahmasb's help, he even attempts to stage a dramatic re-enactment, fussily taping the space representing the room scene in the first shot on his floor, and demonstrating where all the props would be, where the actors would be, how long the shot would take; he attempts to act out not just the dialogue but the stage directions as well, intermixed with his impromptu set design. Watching and listening as Panahi attempts to keep everything straight in his head and present it to the camera is delirious, magical: it is like watching a particularly bright and imaginative child at play. He is, in this moment, completely in his element and full of enthusiasm; it's that same enthusiasm that makes it so confusing for us watching to make sense of what he's trying to say and trying to demonstrate, and that enthusiasm that marks him out as perfectly suited to this one task, of telling a story and communicating characters through visual language. And that enthusiasm makes it even more chilling and heartbreaking when, the director pauses for a long moment and an anguished look passes over his face. "If we could tell a film, then why make a film?" he asks darkly, and walks away to be alone. The movie is always deeply aware of what Panahi has lost, and why it causes him such agony, but never does it communicate this with more force and disgust than here.

This Is Not a Film. It is the diary of a man with very, very little to do, and plenty of time to think about not doing it. Especially in the beginning, much of what we see consists of nothing but Panahi eating, watching his old movies and analyzing them, chatting with his lawyer and trying very hard not to get his hopes up, but you can just tell that it's still a punch to the gut when he finds out that even their best attempts to fight his fate will still result jail time at the least: the Iranian government has too much skin in the game to let him off free. In a very weird way, the most salient aspect of the film is not what it reveals about Panahi's personality, nor his lifestyle, nor his filmmaking technique, but that it is, ultimately, the work of a bored man - there is a thing called This Is Not a Film solely because Panahi was prevented from doing anything by force of law, but not being the kind of man who could sit still under indignity like that, he did what he knew how to come to grips with his new, inactive state of life: he made a movie. The last sequence gets into this marvelously: Mirtahmasb is leaving for the night, having set up the camera on a table so Panahi (who professes to know nothing at all about technology) can do some recording in front of it, and just as he's leaving - Panahi filming his departure on an iPhone - someone arrives at the door. There's an infinitely long moment in which the two criminal filmmakers freeze up in pure terror, as unbelievably tense a moment as cinema has to offer, but it turns out that the new arrival is just a temporary custodian, there to take out the trash, and to provide sympathy. So what does Panahi do? He starts interviewing the young man, and in no time at all he's all but made him the start of a one-take documentary, filming him going about his job in a cramped elevator. The marvel is that Panahi can't do anything else but make a movie: it just happens naturally.

This Is Not a Film. It is an act of defiance. It is a provocation. It is a dangerous movie, for the men who made it, and risked who knows what if they were caught. In a career that has been dominated by aggressively political statements - prior to now, Panahi's last three features were all banned in his home country - this is still the boldest, both because of its content, which is taken up to a great degree with the legal hell of trying to get justice in Iran, and simply because it exists at all: it is a great screaming "fuck you!" to authoritarian control of art, to suppression by means of violence, to governmental bullying. The last words spoken are a warning to Panahi not to be seen carrying a camera around, and yet he doesn't really duck out of the way: half hanging back, longingly looking at a world that has been cut off; half daring anybody to come find him, capturing one moment of beauty in the face of all the shit that has come his way.

This Is Not a Film, but it manages to be a bloody great one, anyway.

This Is Not a Film. Because Panahi can't make a film, and co-conspirator Mojtaba Mirtahmasb can't help him. So if this was a film that would mean that they were breaking the law, duh.

This Is Not a Film. It's the psychoanalysis of a filmmaker,, who knows only one process by which he can absorb and discuss the world around him, and has had that taken away from him by the caprice of a terrified totalitarian government. At one point, Panahi tries to lift his spirits by remembering the project that he was developing with the officials took him into custody. With Mirtahmasb's help, he even attempts to stage a dramatic re-enactment, fussily taping the space representing the room scene in the first shot on his floor, and demonstrating where all the props would be, where the actors would be, how long the shot would take; he attempts to act out not just the dialogue but the stage directions as well, intermixed with his impromptu set design. Watching and listening as Panahi attempts to keep everything straight in his head and present it to the camera is delirious, magical: it is like watching a particularly bright and imaginative child at play. He is, in this moment, completely in his element and full of enthusiasm; it's that same enthusiasm that makes it so confusing for us watching to make sense of what he's trying to say and trying to demonstrate, and that enthusiasm that marks him out as perfectly suited to this one task, of telling a story and communicating characters through visual language. And that enthusiasm makes it even more chilling and heartbreaking when, the director pauses for a long moment and an anguished look passes over his face. "If we could tell a film, then why make a film?" he asks darkly, and walks away to be alone. The movie is always deeply aware of what Panahi has lost, and why it causes him such agony, but never does it communicate this with more force and disgust than here.

This Is Not a Film. It is the diary of a man with very, very little to do, and plenty of time to think about not doing it. Especially in the beginning, much of what we see consists of nothing but Panahi eating, watching his old movies and analyzing them, chatting with his lawyer and trying very hard not to get his hopes up, but you can just tell that it's still a punch to the gut when he finds out that even their best attempts to fight his fate will still result jail time at the least: the Iranian government has too much skin in the game to let him off free. In a very weird way, the most salient aspect of the film is not what it reveals about Panahi's personality, nor his lifestyle, nor his filmmaking technique, but that it is, ultimately, the work of a bored man - there is a thing called This Is Not a Film solely because Panahi was prevented from doing anything by force of law, but not being the kind of man who could sit still under indignity like that, he did what he knew how to come to grips with his new, inactive state of life: he made a movie. The last sequence gets into this marvelously: Mirtahmasb is leaving for the night, having set up the camera on a table so Panahi (who professes to know nothing at all about technology) can do some recording in front of it, and just as he's leaving - Panahi filming his departure on an iPhone - someone arrives at the door. There's an infinitely long moment in which the two criminal filmmakers freeze up in pure terror, as unbelievably tense a moment as cinema has to offer, but it turns out that the new arrival is just a temporary custodian, there to take out the trash, and to provide sympathy. So what does Panahi do? He starts interviewing the young man, and in no time at all he's all but made him the start of a one-take documentary, filming him going about his job in a cramped elevator. The marvel is that Panahi can't do anything else but make a movie: it just happens naturally.

This Is Not a Film. It is an act of defiance. It is a provocation. It is a dangerous movie, for the men who made it, and risked who knows what if they were caught. In a career that has been dominated by aggressively political statements - prior to now, Panahi's last three features were all banned in his home country - this is still the boldest, both because of its content, which is taken up to a great degree with the legal hell of trying to get justice in Iran, and simply because it exists at all: it is a great screaming "fuck you!" to authoritarian control of art, to suppression by means of violence, to governmental bullying. The last words spoken are a warning to Panahi not to be seen carrying a camera around, and yet he doesn't really duck out of the way: half hanging back, longingly looking at a world that has been cut off; half daring anybody to come find him, capturing one moment of beauty in the face of all the shit that has come his way.

This Is Not a Film, but it manages to be a bloody great one, anyway.