Stalin for time

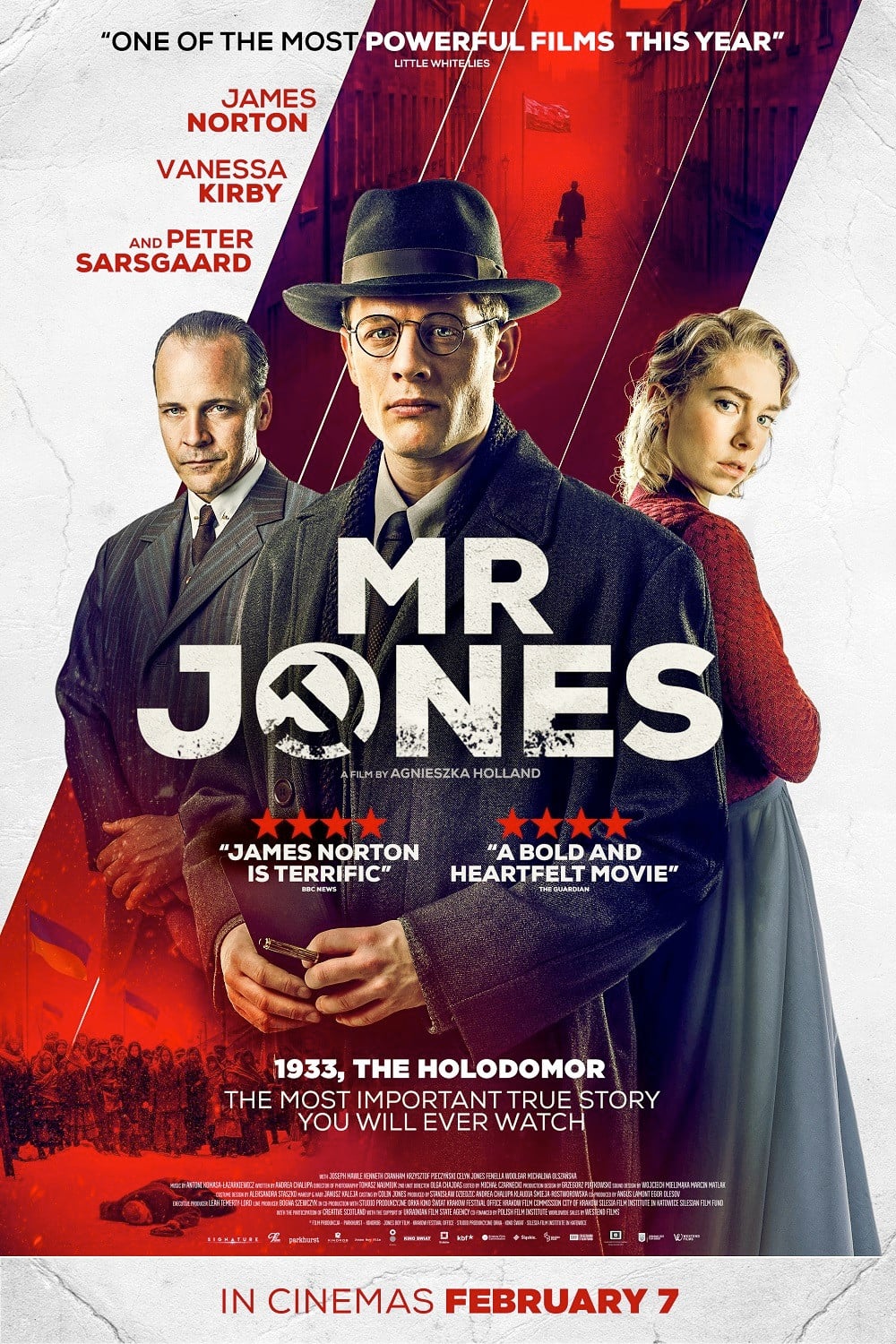

The great Polish director Agnieszka Holland is in the pantheon of European master filmmakers whose work we are more or less required to grapple with, if we take seriously the idea that cinema is an art form. And in this light, it's not surprising that Mr. Jones, a political history lesson that premiered at the Berlinale in 2019 and then took eight months to make its first non-festival appearance, is a superlatively well-directed movie. It's not that the stylistic gestures the film makes are especially shocking or unprecedented, but to make them, and to make them so often, in a film of this genre, speaks to a refusal to ease up on the viewer when easing up will allow them to experience a film comfortably. This is a movie about shocking, unsettling things; so let the viewer be shocked and unsettled.

On the other hand, eight months from world premiere to first release in commercial theaters in its native Poland (and a full year before it showed up basically anywhere else) is not a good sign by any stretch of the imagination, and here's where we have to get to the dark, ugly truth about Mr. Jones: it doesn't really work. The film is the solitary credit in any capacity for writer-producer Andrea Chalupa, and while I'm not sure that I'd have been able to guess "this is a first-time writer" out of all the possible choices for what's wrong it the script, it's not a very surprising fact to have learned. Mr. Jones has the almost vibratory enthusiasm of a morally righteous passion project: something horrible happened in the world, and we have to use the power of The Cinema to tell everybody about it right now! Except that the events in question precede the film's release by almost three-quarters of a century, so in principle there should have been plenty of time to figure out a way to lash them into a tight narrative structure.

Instead, Mr. Jones feels weirdly shapeless, several clumps of story material crammed in next to each other with a kind of allergy to smoothness or artfulness or creativity, or basically other than just reading directly out of a history book. This is most aggressive in the end, when the main narrative thrust has run out, but the lesson isn't over, so it just adds extra scenes. The festival cut of the film was more than 20 minutes longer than the one given commercial release, and it would be interesting to know what exactly was cut; it's easy to imagine a longer version of the film having the room to transition between sequences more fluidly, but it's just as easy to imagine it being an even longer cluster of disjointed "this happened and then this happened"-style scenes.

The history being recounted, anyways, is that of Mr. Gareth Jones (James Norton), a freelance Welsh journalist in the mid-1930s who, in this telling at least, had a bit of a Cassandra-like gift for seeing exactly where the political winds were blowing, much too early for the comfort of those around him. His big calling card was an interview with Chancellor Adolf Hitler of Germany, which convinced him well before anybody else was willing to see it that the newly-installed Nazi party was looking to start aggressively expanding across Europe, and while he had the ear of former Prime Minister David Lloyd George (Kenneth Cranham), that wasn't really enough to do anything for him. Still, it put him on the "nice chats with foreign dictators" beat, and in that capacity, he hoped to similarly interview Josef Stalin. Instead, his trip to the Soviet Union put him in a position to witness firsthand the famines in Ukraine that nobody was willing to openly talk about, what with the Soviet Union and United Kingdom already considering the uneasy patnership that would eventually form the nucleus of the Allied Forces once war broke out a few years down the line, and what with the much-heralded journalist Walter Duranty (Peter Sarsgaard) assuring the world that of course there's no famine, and of course the famine that isn't there has nothing to do with Stalin's conscious decision to sacrifice Ukrainian lives as part of a mad strategy to make the Soviet Union look financially solvent on paper despite being just as crushed by the global economic depression as the rest of the world.

That's the film's message, basically: the Holodomor (the Ukrainian name of this famine, with an emphasis on the ways it which it was man-made and possibly even a deliberate act of genocide) existed, and hasn't been publicised enough,and we might not even know about at all if not for Jones's actions, in the face of great institutional hostility and at great personal risk, in telling the world outside the Soviet Union that it existed. This is not at all the same thing as being a story, and turning this into a story is where Mr. Jones can't quite figure things out. Individual scenes work: Norton's guileless is a little much in the scenes where he has to navigate the complex bureaucracies running Eastern Europe in the '30s, but it serves him in excellent stead when Jones arrives in the heart of the famine and is shocked to his core by the bleak horrors he sees. Sarsgaard's greasy, lizardlike performance as Duranty moves much too far in the direction of unabashed melodrama, but there's no denying it's arresting to watch. Vanessa Kirby, as Duranty's colleague Ada Brooks, who finds herself torn between professional obligations and the ghastly truth, is stuck with a pretty unrewarding role, but in her aghast reactions do what they need to.

And, to bring it all back full circle, Holland is directing the hell out of this. But she's directing to compensate for the script, not to augment or accentuate it. The deeper into the film we get, the harder it is to shake the feeling that the only thing holding it together at all is Holland and cinematographer Tomasz Naumiuk's use of shaky long takes that whip around spaces like the camera is running to keep up with the characters and their conversations, or with the sudden bursts of jagged editing. It's certainly exciting, and it certainly gives Mr. Jones some kind of wired sense of danger that suits it well, but it's fighting the shagginess of the script at every turn. And it's such a shaggy script, piling on scenes, dragging in George Orwell (Joseph Mawle) against historical fact to bizarrely insist that the most interesting thing about Jones's work was that it inspired the writing of Animal Farm (which it didn't, and if it did, that wouldn't be the most important thing about it anyway), and ending up declaring that Duranty, not Stalin, is the real villain of the affair. In its extreme zeal to be good history before being good cinema, Mr. Jones ends up being neither, though Holland is doing everything in her power to at least offer the arresting simulation of the latter.

On the other hand, eight months from world premiere to first release in commercial theaters in its native Poland (and a full year before it showed up basically anywhere else) is not a good sign by any stretch of the imagination, and here's where we have to get to the dark, ugly truth about Mr. Jones: it doesn't really work. The film is the solitary credit in any capacity for writer-producer Andrea Chalupa, and while I'm not sure that I'd have been able to guess "this is a first-time writer" out of all the possible choices for what's wrong it the script, it's not a very surprising fact to have learned. Mr. Jones has the almost vibratory enthusiasm of a morally righteous passion project: something horrible happened in the world, and we have to use the power of The Cinema to tell everybody about it right now! Except that the events in question precede the film's release by almost three-quarters of a century, so in principle there should have been plenty of time to figure out a way to lash them into a tight narrative structure.

Instead, Mr. Jones feels weirdly shapeless, several clumps of story material crammed in next to each other with a kind of allergy to smoothness or artfulness or creativity, or basically other than just reading directly out of a history book. This is most aggressive in the end, when the main narrative thrust has run out, but the lesson isn't over, so it just adds extra scenes. The festival cut of the film was more than 20 minutes longer than the one given commercial release, and it would be interesting to know what exactly was cut; it's easy to imagine a longer version of the film having the room to transition between sequences more fluidly, but it's just as easy to imagine it being an even longer cluster of disjointed "this happened and then this happened"-style scenes.

The history being recounted, anyways, is that of Mr. Gareth Jones (James Norton), a freelance Welsh journalist in the mid-1930s who, in this telling at least, had a bit of a Cassandra-like gift for seeing exactly where the political winds were blowing, much too early for the comfort of those around him. His big calling card was an interview with Chancellor Adolf Hitler of Germany, which convinced him well before anybody else was willing to see it that the newly-installed Nazi party was looking to start aggressively expanding across Europe, and while he had the ear of former Prime Minister David Lloyd George (Kenneth Cranham), that wasn't really enough to do anything for him. Still, it put him on the "nice chats with foreign dictators" beat, and in that capacity, he hoped to similarly interview Josef Stalin. Instead, his trip to the Soviet Union put him in a position to witness firsthand the famines in Ukraine that nobody was willing to openly talk about, what with the Soviet Union and United Kingdom already considering the uneasy patnership that would eventually form the nucleus of the Allied Forces once war broke out a few years down the line, and what with the much-heralded journalist Walter Duranty (Peter Sarsgaard) assuring the world that of course there's no famine, and of course the famine that isn't there has nothing to do with Stalin's conscious decision to sacrifice Ukrainian lives as part of a mad strategy to make the Soviet Union look financially solvent on paper despite being just as crushed by the global economic depression as the rest of the world.

That's the film's message, basically: the Holodomor (the Ukrainian name of this famine, with an emphasis on the ways it which it was man-made and possibly even a deliberate act of genocide) existed, and hasn't been publicised enough,and we might not even know about at all if not for Jones's actions, in the face of great institutional hostility and at great personal risk, in telling the world outside the Soviet Union that it existed. This is not at all the same thing as being a story, and turning this into a story is where Mr. Jones can't quite figure things out. Individual scenes work: Norton's guileless is a little much in the scenes where he has to navigate the complex bureaucracies running Eastern Europe in the '30s, but it serves him in excellent stead when Jones arrives in the heart of the famine and is shocked to his core by the bleak horrors he sees. Sarsgaard's greasy, lizardlike performance as Duranty moves much too far in the direction of unabashed melodrama, but there's no denying it's arresting to watch. Vanessa Kirby, as Duranty's colleague Ada Brooks, who finds herself torn between professional obligations and the ghastly truth, is stuck with a pretty unrewarding role, but in her aghast reactions do what they need to.

And, to bring it all back full circle, Holland is directing the hell out of this. But she's directing to compensate for the script, not to augment or accentuate it. The deeper into the film we get, the harder it is to shake the feeling that the only thing holding it together at all is Holland and cinematographer Tomasz Naumiuk's use of shaky long takes that whip around spaces like the camera is running to keep up with the characters and their conversations, or with the sudden bursts of jagged editing. It's certainly exciting, and it certainly gives Mr. Jones some kind of wired sense of danger that suits it well, but it's fighting the shagginess of the script at every turn. And it's such a shaggy script, piling on scenes, dragging in George Orwell (Joseph Mawle) against historical fact to bizarrely insist that the most interesting thing about Jones's work was that it inspired the writing of Animal Farm (which it didn't, and if it did, that wouldn't be the most important thing about it anyway), and ending up declaring that Duranty, not Stalin, is the real villain of the affair. In its extreme zeal to be good history before being good cinema, Mr. Jones ends up being neither, though Holland is doing everything in her power to at least offer the arresting simulation of the latter.