No place like Holmes

There are so god-damned many film and television incarnations of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle's iconic misanthropic detective, it would be ludicrous to make a definitive claim about any of them being the best or worst, the most or least faithful, or just about anything else. But I will nudge far enough into this dangerous territory to say that I have not personally seen any version of Holmes that gave me less pleasure than director Guy Ritchie's 2009 Sherlock Holmes and 2011 Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, which turned the brilliant thinker into a steampunk martial arts expert and surrounded him by a frantic whirlwind of cutting, visual effects, and overindulgent production design that firmly demonstrated for the first time (and, most regrettably, not the last) that Ritchie's extremely distinctive filmmaking style was not a very good fit for costume drama.

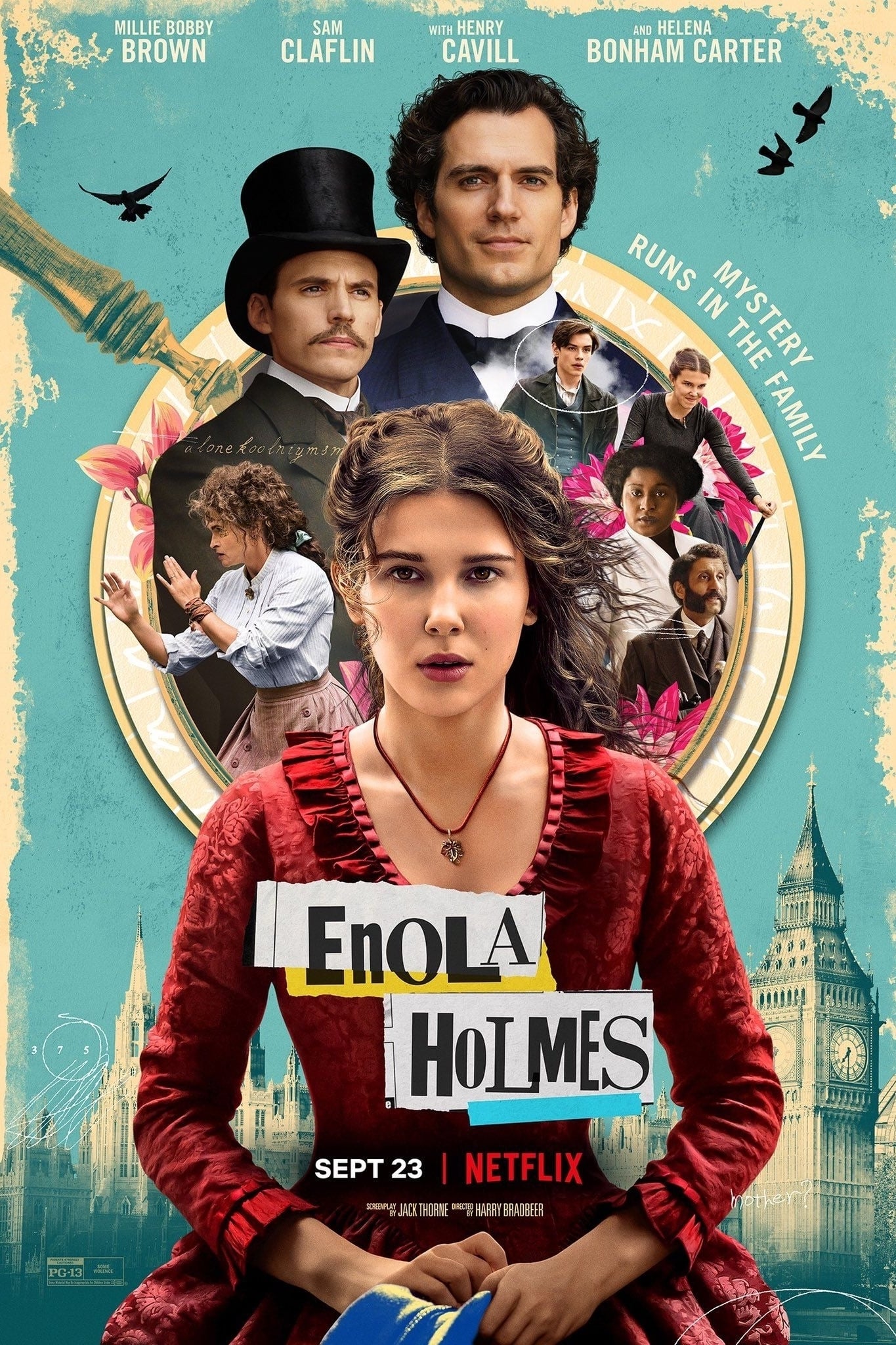

That being said, we've apparently hit a point in culture where Ritchie's films are Sherlock Holmes, or at least enough so that for no other apparent reason, director Harry Bradbeer, a TV veteran of some acclaim,* has looked to those films as his chief stylistic inspiration in crafting Enola Holmes, a kind of spin-off of the character. In the film, based upon Nancy Springer's 2000s series of young adult novels, Enola (Millie Bobby Brown) is Sherlock's (Henry Cavill) much younger teen sister, so much younger that he and eldest brother Mycroft (Sam Claflin) mostly try not to think about her. When their mother (Helena Bonham Carter) inexplicably disappears one morning, Enola goes off on a quest to find her, which necessarily means avoiding her irritated, meddlesome brothers who are trying to deposit her into a finishing school run by the harridan Miss Harrison (Fiona Shaw); this also snowballs into investigating her first case, the mystery of who is trying to kill Viscount Tewkesbury (Louis Partridge), a cute boy her own age who is also about to be seated in the House of Lords, following the suspicious death of his father, the Lord Tewkesbury.

Perfect innocuous stuff; giving Sherlock Holmes a whip-smart younger sister is exactly the kind of fannish addition to the source material can give it a fresh, playful feeling, if it's done well. The problem is that Enola Holmes hasn't done it well, and this gets back to that first point: this is a Holmes spin-off (or whatever we want to call it) for which the favored model of "real" Holmes storytelling are the cluttered, noisy, manic, ugly, and just plain dumb Ritchie films. And say what one will about the Ritchie films - as indeed I just said five things - but at least Guy Ritchie made them himself. They come by their stylistic excess honestly and organically. Bradbeer, meanwhile, is strenuously copying Ritchie's aesthetic, and it's not organic at all; every snappy visual punchline of a choppy cut, every animated intertitle, every bulbous use of a wide-angle lens, feels extremely methodical, which is entirely fatal to this kind of style. If it's going to work at all, it needs to work because it feels like everybody on set and behind the camera was channeling some kind of shared mania, and was just vomiting up style without thinking about it. It must have a fearless messiness, if it is to have any messiness. And Enola Holmes has a very manicured, deliberate messiness that is just the fucking dreariest thing. Seriously, it is an exhausting film to watch, all florid, wild nonsense that feels like it's being played at 75% speed.

The most obvious example, and also the most enervating to me, is the film's addiction to breaking the fourth wall: screenwriter Jack Thorne keeps having Enola, right in the middle of scenes with other characters, switch over into narrator mode and chats with us in her very wordy manner. This happens almost constantly in the first quarter or so of the 123-minute film (oh, that's another thing; this has a simply immoral running time for its trivial quantity of plot, though to be fair that's because it's spending the last third of its running time planting seeds for the franchise it transparently wants to build), and it never works even a single time. The sluggish pacing is part of it: Brown's looks into the camera all feel like she's slowly and effortfully winding her entire face up, so that she can give the appropriate litany of heavy eye rolls and side glances towards us and exaggerated twists to her mouth. The mugging is bad enough; the way that she foreshadows the mugging, that Bradbeer arranges things so that we can feel the mugging coming upon us like a wave of stormclouds, that's what makes it painful. And so, frankly does the zippy, mindless energy of the writing; Enola may be stated to be Sherlock's intellectual equal, but these endless direct-address marathons present her as somebody who cannot follow an individual thought to completion without tripping over three or four other ones on the way.

All this being said, I'd still rather watch this than the Ritchie films, if only because it takes place in something that meaningfully resembles Victorian London, and has a narrative that largely revolves around an observant investigator finding and then correctly interpreting clues. Enola's detective skills are a little undernourished, based on the evidence we actually get: mostly, she seems to be very good at word jumbles, and solving puzzles rather than piecing together shards of inadvertent evidence. Indeed, she misidentifies the main villain and only learns their true identity when they step into a shadowy hallway and state, essentially in so many words, "aha, it was actually me all along". Still, the Ritchie films didn't even give us this much. And Enola Holmes also has some good location shooting and outdoor sets that feel like they have a bustling physical presence, enough to make it feel like it exists somewhere real.

Besides all of which, the story is at least solid; the mystery angle is undernourished, but it is a children's movie at heart, and it's not trying to overwhelm us with its cunning, but make sure we're keeping up. The B-plot of Sherlock and Mycroft hunting Enola could certainly do with some trimming (not least because Cavill and Claflin are both pretty stiff; Brown, mugging and all, at least appears to be having fun), and it's annoying how blatantly everything involving Enola's mother is there to lead us into future films, rather than to do anything in this film; it is doubly annoying in that Bonham Carter is so far and away the best actor in the cast that it's almost hard to quantify it, bringing an alert, tense liveliness that feels more authentic and human than anything being done by all three of her screen children put together, and she's doing it with less than five minutes of cumulative screentime, and I just really want her movie. Still, the bones of the thing are good, and the idea of a children's Holmes variant based around his younger sister chafing at the gender roles of Victorian England when all she wants to do is go out and be a master detective is precisely the right amount of clever without being smug. I cannot imagine that a sequel will correct this film's faults, but I can it least imagine that it could, and there are enough strengths to give it something to grow on.

*Most notably, he directed all but the first episode of Fleabag, which I imagine is what got him the job here.

That being said, we've apparently hit a point in culture where Ritchie's films are Sherlock Holmes, or at least enough so that for no other apparent reason, director Harry Bradbeer, a TV veteran of some acclaim,* has looked to those films as his chief stylistic inspiration in crafting Enola Holmes, a kind of spin-off of the character. In the film, based upon Nancy Springer's 2000s series of young adult novels, Enola (Millie Bobby Brown) is Sherlock's (Henry Cavill) much younger teen sister, so much younger that he and eldest brother Mycroft (Sam Claflin) mostly try not to think about her. When their mother (Helena Bonham Carter) inexplicably disappears one morning, Enola goes off on a quest to find her, which necessarily means avoiding her irritated, meddlesome brothers who are trying to deposit her into a finishing school run by the harridan Miss Harrison (Fiona Shaw); this also snowballs into investigating her first case, the mystery of who is trying to kill Viscount Tewkesbury (Louis Partridge), a cute boy her own age who is also about to be seated in the House of Lords, following the suspicious death of his father, the Lord Tewkesbury.

Perfect innocuous stuff; giving Sherlock Holmes a whip-smart younger sister is exactly the kind of fannish addition to the source material can give it a fresh, playful feeling, if it's done well. The problem is that Enola Holmes hasn't done it well, and this gets back to that first point: this is a Holmes spin-off (or whatever we want to call it) for which the favored model of "real" Holmes storytelling are the cluttered, noisy, manic, ugly, and just plain dumb Ritchie films. And say what one will about the Ritchie films - as indeed I just said five things - but at least Guy Ritchie made them himself. They come by their stylistic excess honestly and organically. Bradbeer, meanwhile, is strenuously copying Ritchie's aesthetic, and it's not organic at all; every snappy visual punchline of a choppy cut, every animated intertitle, every bulbous use of a wide-angle lens, feels extremely methodical, which is entirely fatal to this kind of style. If it's going to work at all, it needs to work because it feels like everybody on set and behind the camera was channeling some kind of shared mania, and was just vomiting up style without thinking about it. It must have a fearless messiness, if it is to have any messiness. And Enola Holmes has a very manicured, deliberate messiness that is just the fucking dreariest thing. Seriously, it is an exhausting film to watch, all florid, wild nonsense that feels like it's being played at 75% speed.

The most obvious example, and also the most enervating to me, is the film's addiction to breaking the fourth wall: screenwriter Jack Thorne keeps having Enola, right in the middle of scenes with other characters, switch over into narrator mode and chats with us in her very wordy manner. This happens almost constantly in the first quarter or so of the 123-minute film (oh, that's another thing; this has a simply immoral running time for its trivial quantity of plot, though to be fair that's because it's spending the last third of its running time planting seeds for the franchise it transparently wants to build), and it never works even a single time. The sluggish pacing is part of it: Brown's looks into the camera all feel like she's slowly and effortfully winding her entire face up, so that she can give the appropriate litany of heavy eye rolls and side glances towards us and exaggerated twists to her mouth. The mugging is bad enough; the way that she foreshadows the mugging, that Bradbeer arranges things so that we can feel the mugging coming upon us like a wave of stormclouds, that's what makes it painful. And so, frankly does the zippy, mindless energy of the writing; Enola may be stated to be Sherlock's intellectual equal, but these endless direct-address marathons present her as somebody who cannot follow an individual thought to completion without tripping over three or four other ones on the way.

All this being said, I'd still rather watch this than the Ritchie films, if only because it takes place in something that meaningfully resembles Victorian London, and has a narrative that largely revolves around an observant investigator finding and then correctly interpreting clues. Enola's detective skills are a little undernourished, based on the evidence we actually get: mostly, she seems to be very good at word jumbles, and solving puzzles rather than piecing together shards of inadvertent evidence. Indeed, she misidentifies the main villain and only learns their true identity when they step into a shadowy hallway and state, essentially in so many words, "aha, it was actually me all along". Still, the Ritchie films didn't even give us this much. And Enola Holmes also has some good location shooting and outdoor sets that feel like they have a bustling physical presence, enough to make it feel like it exists somewhere real.

Besides all of which, the story is at least solid; the mystery angle is undernourished, but it is a children's movie at heart, and it's not trying to overwhelm us with its cunning, but make sure we're keeping up. The B-plot of Sherlock and Mycroft hunting Enola could certainly do with some trimming (not least because Cavill and Claflin are both pretty stiff; Brown, mugging and all, at least appears to be having fun), and it's annoying how blatantly everything involving Enola's mother is there to lead us into future films, rather than to do anything in this film; it is doubly annoying in that Bonham Carter is so far and away the best actor in the cast that it's almost hard to quantify it, bringing an alert, tense liveliness that feels more authentic and human than anything being done by all three of her screen children put together, and she's doing it with less than five minutes of cumulative screentime, and I just really want her movie. Still, the bones of the thing are good, and the idea of a children's Holmes variant based around his younger sister chafing at the gender roles of Victorian England when all she wants to do is go out and be a master detective is precisely the right amount of clever without being smug. I cannot imagine that a sequel will correct this film's faults, but I can it least imagine that it could, and there are enough strengths to give it something to grow on.

*Most notably, he directed all but the first episode of Fleabag, which I imagine is what got him the job here.