Amicus Horror: Sade face

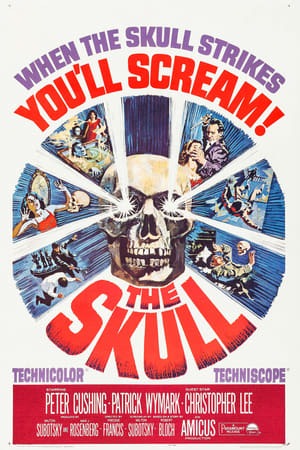

It of course doesn't describe every one of the studio's 28 features, not even most of them, but I think there's a fairly clear platonic ideal of an Amicus Productions film: a horror anthology, directed by Freddie Francis, with a script adapted from the work of author Robert Bloch, starring Peter Cushing. 1965's The Skull, the studio's second horror film, gets us almost all the way there: it's not an anthology film. And while it is indeed adapted from Bloch's short story "The Skull of the Marquis de Sade", I feel like it would be even better if it had a screenplay written by Bloch. Instead, the adaptation was done by studio head Milton Subotsky, though Francis insisted afterwards that what Subotsky provided was more of a sketch, and the script had to be bulked up later on to provide the actual material for a feature.

But disregarding all of that, I think it's still fair to say that The Skull finds Amicus pretty comfortably settling into the groove of being Amicus, several months after Dr. Terrible's House of Horrors successfully transitioned the company to the work of making horror films. Though it's worth noting that Amicus was keeping its options open at this point: the same week that The Skull opened, the company released its first sci-fi movie, the TV adaptation Dr. Who and the Daleks (given the films' immediate proximity, I would be tempted to assume they were released as a double feature, but a cursory search turns up no evidence of such a thing). And that's well and good, especially since Dr. Who made quite a substantial amount of money for Amicus, but The Skull is proof enough that focusing on horror films was going to be a good strategy for Subotsky and producing partner Max Rosenberg going forward: it's a damn good example of the form, brazenly creative in ways that very much feel like what you get when the guys in second place decide to show off so that everybody can see how exciting and ambitious they can be, compared to the guys in first.

That being Hammer Film Productions, of course, and The Skull opens with a sequence that I cannot possibly take to be anything but a direct, deliberate pastiche of Hammer's style. We open in an as-yet indeterminate period, but it's certainly a costume drama epoch (it is, in fact, the late 1810s), and the very first shot positions us squarely in the realm of stately Gothic horror, with gloomy shadows pouring over the ground of a very moody and very artificial-looking graveyard, first spied through the bars of an iron fence. Before too long, this sequence will be over and we'll skip ahead to England in the 1960s, but it's a faultless Hammer riff up to that point, from the beautifully stagey location to the inclusion of some saucy almost-nudity, the form of a woman (April Olrich) taking a bath when her grave-robbing lover (Maurice Good) comes in, positioned juuuuust right so that we can never see anything.

It's all very fun and tongue-in-cheek, ending on its must fun and tongue-in-cheek touch when the grave robber, having boiled the flesh off the skull he's just stolen, dies offscreen in some manner so appalling that they can't even show it onscreen; we just see and hear the woman screaming in a frenzy (Olrich is a fantastic screamer, it turns out). As a matter of fact, we'll return to this moment later in the movie, and it's quite a disappointment to discover that it's not really very appalling at all, but in this moment, as we crash into the opening credits sequence, it's nice to have room to think whatever wretched, nightmarish things we want.

The movie then arrives at its main plot, which starts on the friendly competition between dueling collectors of occult curios, Christopher Maitland (Cushing) and Sir Matthew Phillips ("special guest star" Christopher Lee). They're buying this or that ugly little demonic gewgaw at auction, and Sir Matthew has gotten the better haul this time around, but Maitland is shortly thereafter visited by his shady dealer, Anthony Marco (Patrick Wymark). Marco has a few of the usual spooky odds and ends, but he also has something pretty special and bizarre this time: a skull that he claims to be the former possession of Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade. Maitland is both curious and dubious, but soon enough he learns that the skull is the real deal that it was stolen from Sir Matthew's possession, and that Sir Matthew is extremely glad to be rid of it. Before Maitland has a chance to buy it off of Marco, though, the dealer ends up dead, under extremely suspicious circumstances; Maitland, who discovered the body, takes this opportunity to acquire the skull for free.

Thus far, and we're about half through the movie, maybe a little less, The Skull has done absolutely nothing to distinguish itself. It is, to be sure, a very solid and satisfying version of bog-standard horror stuff. Cushing in is outstanding form throughout, perhaps taking license from the de Sade connection to play Maitland as someone whose fascination with the occult has a distinctly perverse element, though one buried deep in the foundations of the performance - it's not a kinky performance, and I don't think I can imagine (and certainly want to) what a thoroughly kinky Cushing performance might even look like. But there's a definite, albeit subdued hint of fetishism in the way he hungrily discusses his collection, aided and abetted by the way that Francis and cinematographer John Wilcox frame and light Cushing's face. His eyes get a lot of attention in this movie, close and bright in all their watery blue glory, and there's something almost distressingly intimate about it. My mental model for Cushing is that he has deep eye sockets that tend to catch shadows; seeing him with such strong eye lights that get so much focus gives his character's unspoken inner life and thoughts a forcefulness that feels a bit quietly monstrous, beneath all of the usual Cushing primness.

It is, in general, a film with some really interesting, forceful compositions. Some fun ones, too; setting the camera "inside" the skull to watch conversations through its empty eye sockets is goofy as hell, but its used at such a well-chosen point the transition us between scenes that I'll let the filmmakers have it. Otherwise, Francis's strategy is to make sure that the skull always has a prominent spot in the composition, building the entire frame to draw attention to whatever plane of action and whatever negative space houses the skull, just to make sure we're always aware of it. It's neither his most complex nor adventurous work as a director, and doesn't draw on his history as a cinematographer as much as some of his best films do, but it's more than enough to put over this strait-faced silliness about the haunted skull of a man whom the film has decided to pretend was a warlock, or I don't even know what. Not just a sex criminal and politically incendiary author of dirty books, I can tell you that (indeed, the Marquis's literary habits aren't even really touched on, and the expressly sexual elements of his attitudes have been scrubbed free and replaced with generic "love of cruelty" boilerplate. I imagine this is why Cushing felt the need to bring some of that back in). It's all very straightforward, but executed well enough; I wasn't excited, but I wasn't at all dissatisfied, either.

Then, somewhere along the line, the skull starts to work on Maitland, and the movie takes a major step up in quality, interest, and just plain all-around weirdness. I think it would be exaggerating to call it "psychedelic", especially given that in 1965, psychedelia was just starting to show up on the edges of the mainstream. But it has a definitely tinge of psychedelic terror to go along with its garishly colored Surrealism. Basically, Maitland experiences what can only rightfully be called a dream sequence, though it seems to happen while he's awake and existing in the real world, and while it looks pretty quaint by 21st Century standards, this is a sequence predating literally all of the analogues I would ordinarily think to compare it to. I mean, I can say that it looks like a combination of David Lynch and Mario Bava made by buttoned-up Brits for a buttoned-up audience, but that's 2020 talking - Lynch was more than a decade in the future, and I strongly doubt Francis and company had access to Bava at all, and certainly not his color films. So where in God's name does this blood-red freakout come from?

That's enough to get me excited, and it's still just an appetizer for the film's bravura final act, in which Maitland flops and flails his way around as the skull torments him. For well more than a whole reel - Wikipedia pegs it at 25 minutes, and that seems long, but maybe it was just inordinately well-paced - there's basically no dialogue, basically no story, just a protracted sequence of Cushing sweating and looking panicked as the camera presses up against him, wringing every drop of terror from his face in close-up, and backing off to watch him throw his body around the set. I'm very certain that I'm not selling it all, but it is one-of-a-kind gripping stuff, one of the strangest exercises in pure terrified torment that a horror B-movie in the '60s was ever likely to indulge in. Cushing is a perfect actor to carry it off, too. Especially given how mildly by-the-books the first part of the movie was, this incredible swerve at the end makes The Skull vastly more fascinating than I was at all prepared for, and while I admit that the film perhaps lands at "interesting" more than necessarily "good", that's still a hell of a lot, and continues to demonstrate that, in its early years at least, Amicus was using its second-tier status as an excuse to go bonkers, rather than to play everything safe in the hopes of carving out a market niche.

But disregarding all of that, I think it's still fair to say that The Skull finds Amicus pretty comfortably settling into the groove of being Amicus, several months after Dr. Terrible's House of Horrors successfully transitioned the company to the work of making horror films. Though it's worth noting that Amicus was keeping its options open at this point: the same week that The Skull opened, the company released its first sci-fi movie, the TV adaptation Dr. Who and the Daleks (given the films' immediate proximity, I would be tempted to assume they were released as a double feature, but a cursory search turns up no evidence of such a thing). And that's well and good, especially since Dr. Who made quite a substantial amount of money for Amicus, but The Skull is proof enough that focusing on horror films was going to be a good strategy for Subotsky and producing partner Max Rosenberg going forward: it's a damn good example of the form, brazenly creative in ways that very much feel like what you get when the guys in second place decide to show off so that everybody can see how exciting and ambitious they can be, compared to the guys in first.

That being Hammer Film Productions, of course, and The Skull opens with a sequence that I cannot possibly take to be anything but a direct, deliberate pastiche of Hammer's style. We open in an as-yet indeterminate period, but it's certainly a costume drama epoch (it is, in fact, the late 1810s), and the very first shot positions us squarely in the realm of stately Gothic horror, with gloomy shadows pouring over the ground of a very moody and very artificial-looking graveyard, first spied through the bars of an iron fence. Before too long, this sequence will be over and we'll skip ahead to England in the 1960s, but it's a faultless Hammer riff up to that point, from the beautifully stagey location to the inclusion of some saucy almost-nudity, the form of a woman (April Olrich) taking a bath when her grave-robbing lover (Maurice Good) comes in, positioned juuuuust right so that we can never see anything.

It's all very fun and tongue-in-cheek, ending on its must fun and tongue-in-cheek touch when the grave robber, having boiled the flesh off the skull he's just stolen, dies offscreen in some manner so appalling that they can't even show it onscreen; we just see and hear the woman screaming in a frenzy (Olrich is a fantastic screamer, it turns out). As a matter of fact, we'll return to this moment later in the movie, and it's quite a disappointment to discover that it's not really very appalling at all, but in this moment, as we crash into the opening credits sequence, it's nice to have room to think whatever wretched, nightmarish things we want.

The movie then arrives at its main plot, which starts on the friendly competition between dueling collectors of occult curios, Christopher Maitland (Cushing) and Sir Matthew Phillips ("special guest star" Christopher Lee). They're buying this or that ugly little demonic gewgaw at auction, and Sir Matthew has gotten the better haul this time around, but Maitland is shortly thereafter visited by his shady dealer, Anthony Marco (Patrick Wymark). Marco has a few of the usual spooky odds and ends, but he also has something pretty special and bizarre this time: a skull that he claims to be the former possession of Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade. Maitland is both curious and dubious, but soon enough he learns that the skull is the real deal that it was stolen from Sir Matthew's possession, and that Sir Matthew is extremely glad to be rid of it. Before Maitland has a chance to buy it off of Marco, though, the dealer ends up dead, under extremely suspicious circumstances; Maitland, who discovered the body, takes this opportunity to acquire the skull for free.

Thus far, and we're about half through the movie, maybe a little less, The Skull has done absolutely nothing to distinguish itself. It is, to be sure, a very solid and satisfying version of bog-standard horror stuff. Cushing in is outstanding form throughout, perhaps taking license from the de Sade connection to play Maitland as someone whose fascination with the occult has a distinctly perverse element, though one buried deep in the foundations of the performance - it's not a kinky performance, and I don't think I can imagine (and certainly want to) what a thoroughly kinky Cushing performance might even look like. But there's a definite, albeit subdued hint of fetishism in the way he hungrily discusses his collection, aided and abetted by the way that Francis and cinematographer John Wilcox frame and light Cushing's face. His eyes get a lot of attention in this movie, close and bright in all their watery blue glory, and there's something almost distressingly intimate about it. My mental model for Cushing is that he has deep eye sockets that tend to catch shadows; seeing him with such strong eye lights that get so much focus gives his character's unspoken inner life and thoughts a forcefulness that feels a bit quietly monstrous, beneath all of the usual Cushing primness.

It is, in general, a film with some really interesting, forceful compositions. Some fun ones, too; setting the camera "inside" the skull to watch conversations through its empty eye sockets is goofy as hell, but its used at such a well-chosen point the transition us between scenes that I'll let the filmmakers have it. Otherwise, Francis's strategy is to make sure that the skull always has a prominent spot in the composition, building the entire frame to draw attention to whatever plane of action and whatever negative space houses the skull, just to make sure we're always aware of it. It's neither his most complex nor adventurous work as a director, and doesn't draw on his history as a cinematographer as much as some of his best films do, but it's more than enough to put over this strait-faced silliness about the haunted skull of a man whom the film has decided to pretend was a warlock, or I don't even know what. Not just a sex criminal and politically incendiary author of dirty books, I can tell you that (indeed, the Marquis's literary habits aren't even really touched on, and the expressly sexual elements of his attitudes have been scrubbed free and replaced with generic "love of cruelty" boilerplate. I imagine this is why Cushing felt the need to bring some of that back in). It's all very straightforward, but executed well enough; I wasn't excited, but I wasn't at all dissatisfied, either.

Then, somewhere along the line, the skull starts to work on Maitland, and the movie takes a major step up in quality, interest, and just plain all-around weirdness. I think it would be exaggerating to call it "psychedelic", especially given that in 1965, psychedelia was just starting to show up on the edges of the mainstream. But it has a definitely tinge of psychedelic terror to go along with its garishly colored Surrealism. Basically, Maitland experiences what can only rightfully be called a dream sequence, though it seems to happen while he's awake and existing in the real world, and while it looks pretty quaint by 21st Century standards, this is a sequence predating literally all of the analogues I would ordinarily think to compare it to. I mean, I can say that it looks like a combination of David Lynch and Mario Bava made by buttoned-up Brits for a buttoned-up audience, but that's 2020 talking - Lynch was more than a decade in the future, and I strongly doubt Francis and company had access to Bava at all, and certainly not his color films. So where in God's name does this blood-red freakout come from?

That's enough to get me excited, and it's still just an appetizer for the film's bravura final act, in which Maitland flops and flails his way around as the skull torments him. For well more than a whole reel - Wikipedia pegs it at 25 minutes, and that seems long, but maybe it was just inordinately well-paced - there's basically no dialogue, basically no story, just a protracted sequence of Cushing sweating and looking panicked as the camera presses up against him, wringing every drop of terror from his face in close-up, and backing off to watch him throw his body around the set. I'm very certain that I'm not selling it all, but it is one-of-a-kind gripping stuff, one of the strangest exercises in pure terrified torment that a horror B-movie in the '60s was ever likely to indulge in. Cushing is a perfect actor to carry it off, too. Especially given how mildly by-the-books the first part of the movie was, this incredible swerve at the end makes The Skull vastly more fascinating than I was at all prepared for, and while I admit that the film perhaps lands at "interesting" more than necessarily "good", that's still a hell of a lot, and continues to demonstrate that, in its early years at least, Amicus was using its second-tier status as an excuse to go bonkers, rather than to play everything safe in the hopes of carving out a market niche.

Categories: amicus productions, british cinema, horror