Amicus Horror: You don't have to be mad to work here, but it helps

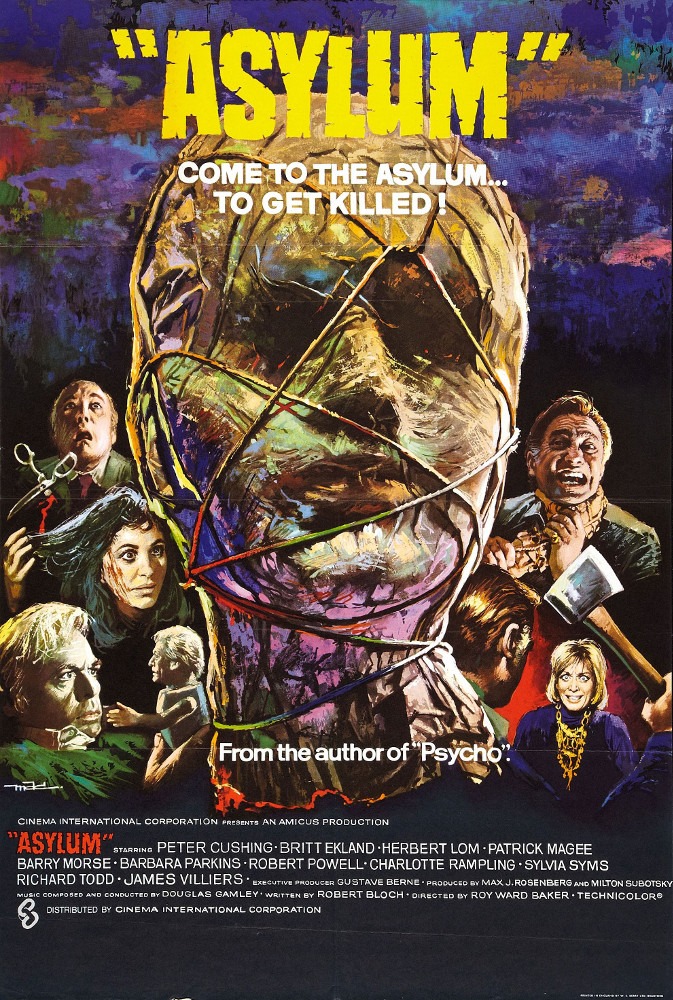

Asylum might have the single best hook of any anthology film I have seen. The story opens with Dr. Martin (Robert Powell), a young psychiatrist, arriving at a remote insane asylum for a job interview. The man who runs the place, Dr. Rutherford (Parick McGee), seems like a bit of an asshole, the kind of person who usually has a position of authority at a movie asylum, who views the patients more as experiments to run than people to help. And he has an experiment in mind right now: if Martin is so good, surely he won't have any problem figuring out which of four particularly misbegotten souls is the former head of the asylum, Dr. Starr, who has had a complete mental breakdown and adopted an entirely new personality. Guided to the hallway where these patients live by orderly Max Reynolds (Geoffrey Bayldon), Martin listens to each of their tales, all surely the sign of a profoundly broken mind. Cue the individual segments, adapted by Robert Bloch from his own short stories.

I regret to say that Asylum's individual tales of madness and terror don't end up entirely live up to the pulpy brilliance of that framing narrative, though it would take a whole hell of a lot for them to do so. And the film sort of knows it: the framing narrative is unusually active, so much so that this stretches the very idea of an "anthology" film (or, to use the favored word of Amicus Productions, who created Asylum, a "portmanteau") to the point where it barely feels like it still applies. The conclusion to the third story is given in the framework, and fourth story takes place within the framing narrative, such that it really doesn't make sense to talk about them as separate things. And even without these things, the framework gets an unusual amount of attention, both stylistically and narratively, starting right from its delightfully tongue-in-cheek opening, with Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain storming across the shots of Martin arriving at the asylum, adding a nice note of over-the-top horror movie grumbling (Mussorgsky will return, in the form of Pictures at an Exhibition, and Douglas Gamley's playfully clichéd "original" score echoing the composer's work as well). There's also an odd sense that the stakes of the framework narrative matter more than the stakes of the individual segments: since we're meeting the narrators of those tales, we know that they're not going to die, and they end up not really resolving in any other way; they reach a point of emotional climax and then leap right back to the storyteller looking aghast while Martin ponders their words.

None of this is a complaint! The good news is that Asylum has the filmmaking chops to compensate for the slightly half-baked feeling of its horrifying little anecdotes. Director Roy Ward Baker had a well-honed talent in genre schlock, having made several pictures for Hammer Films prior to this, the first of three movies he directed at Amicus, and he also had some substantial Hollywood credits to his name, including one of the finest of the '50s 3-D movies, Inferno. Though he is almost unquestionably best-known for the British-made 1958 account of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, A Night to Remember, by general acclaim the most artistically and historically successful film on the subject. He was bringing a lot of different skills to Asylum is what I mean to say, and you see them on display in various throughout the whole movie. But he's going overboard in making the titular asylum seem menacing and disorienting, including a hell of a weird POV shot as Martin looks at creepy sketches hanging on the wall, and the camera cranes around in a way suggesting that the young doctor is currently levitating at a 135-degree angle to the floor.

Anyway, Dr. Martin's first visit is to Bonnie (Barbara Perkins) - Rutherford has already nastily mocked him for presuming that Dr. Starr had to be a "him" - and she tells him the story "Frozen Fear": her lover, Walter (Richard Todd), concocted a plan with her to murder his wife Ruth (Sylvia Syms). And this plan involved hiding her body by chopping it into pieces, wrapping them in brown paper, and stashing them in the big coffin freezer in the basement, later to dispose of them bit by bit. And so this he does, coolly offing his wife in a scene that proceeds with the nastiest briskness and lack of any sort of sentiment: Ruth seems nice, outside of her aggressive jealous streak, Walter is a cold-blooded psychopath, and we've got nowhere to go while we watch him chop her down without so much as breaking into a sweat.

Even for a single segment of an anthology film, that's not nearly enough for an actual story, of course, so it's not at all shocking that there's more to it than that. Ruth, as it so happens, has been studying voodoo lately, and she had a protective charm on when she was dumped into the freezer. This has the unexpected effect of resuscitating all of her pieces, which prove to be astonishingly effective at exacting revenge on her killer, though this is much because he's pinned down in amazed terror as anything else. Meanwhile, Bonnie is due to come around to see how her lover has fared in getting rid of the one big roadblock to their happiness, and what she sees will be just the sort of thing that might make you sound like a gibbering maniac who needs to be sent to an insane asylum, if you tried to describe it to the cops.

One of the fascinating things about Asylum is that every one of the segments has notably different strengths and weaknesses, and in this case, there's no mistaking the strength: the sequence in which Ruth's parts crawl out of the freezer to attack Walter is extraordinarily unnerving, one of the most genuinely scary things in any Amicus film. It gets this in large part by plying one of the simplest tricks it could imaginably play: there's hardly any sound other than music after Ruth dies. And so what plays out is a kind of horrible silent ballet of inexplicable movement, with the wrapped body parts (which look creepy as hell even just sitting there) slowly tugged in front of the lens in little jerks along the ground it has a genuinely otherworldly quality, with the kind of horribly inevitability of a dream you can't wake up from, and as much as the film has given us only reasons to despise Walter, it's hard not to share his frozen fear , if you will, at the eerie sight, filmed by Baker and cinematographer Denys Coop in such an unexceptional realistic mode.

There are different strengths and weaknesses in each segment, I said, and "Frozen Fear" also has its downside: while all three of the segments feel more or less incomplete, the other two at least feel like stories. This one really just feels like a sketch, or an anecdote. None of Bonnie, Walter or Ruth have any personality at all, they're just props in a little chain of man kills wife; man dismembers wife; wife's hand kills him. It's only the fact that the horrifying imagery hits so hard that the segment holds any interest at all.

Martin's next subject is Bruno (Barry Morse), a tailor who recalls the bizarre events of his last job in "The Weird Tailor" - a title which is, if nothing, a world-class self-aware pun. Times have been tough, and he ends up facing an ultimatum from his landlord Stebbins (John Franklyn-Robbins) that he cannot possibly hope to meet. Luck apparently comes to him, though, when a very odd and obviously untrustworthy man calling himself Smith (Peter Cushing) comes by with a piece of extraordinary cloth that seems to glow in multiple colors. He also has an extremely specific set of instructions for how that cloth needs to be cut and sewed, too, and while this all spells bad news, or at least a client who is definitely hiding something, Bruno and his wife Anna (Ann Firbank) are in such desperate straits, and the payday promises to be so lucrative, that the tailor decides to overlook the red flags and muscle through the very odd request. This being the kind of film it is, with the title this segment has, it's not at all a surprise when the suit is being used for an eldritch reason - though also a sad one, if Bruno could see that through his terror.

In a pinch, I'd be inclined to call "The Weird Tailor" the highlight of Asylum: it certainly tells the most complete story of any of the segments. At heart, this is a story of two very sad and very desperate people talking past each other, and the horrible results of this miscommunication, and Morse and Cushing do a great job of embodying those elements of the characters. The balance between the two of them, and the panicky misunderstanding that rises when they confront each other over Smith's secret, is so good that the sequence suffers instantly from the fact that this isn't actually the conflict; there's a whole "act" of the story leftover after the tailor flees Smith's chambers, and it feels oddly-motivated, and a little bit like this was quickly revised to add some stronger horror elements than had initially been part of the story. Still, the acting, and the uncomfortable amount of blank empty spaces that fill many of the interiors in this sequence, keep it working; there's an abstract quality that amplifies the horror, making it disquieting if not actively scary.

The next patient, Barbara (Charlotte Rampling) is unnervingly self-aware: she knows about her own mental disturbances, having been in an asylum once before. And the story of what happened after she was released is told in "Lucy Comes to Stay", which like "The Weird Tailor" feels very little like horror, or a genre film at all, for most of its length; when horror comes in, though, it's generally more organic and inevitable than it was there. Barbara, we learn, was under the thumb of her brother George (James Villiers), and the nurse Miss Higgins (Megs Jenkins), whose treatment of her felt awfully peremptory and authoritarian. Happily, her wonderful friend Lucy (Britt Ekland) pops up just then to help keep her spirits up. Lucy is quite a bit less placid than Barbara, and quite a bit more willing to be a thorn in the sides of George and Higgins, and this initially delights Barbara. But eventually, Lucy's antics take on a more vicious streak.

There's more to it still - I mentioned that this was the segment whose narrative resolution actually takes place in the framing story, and that's a big part of why "Lucy Comes to Stay" feels sort of like it doesn't actually have a narrative. Also because it turns out to be awfully trite, once we get that resolution. Still, there's something magnetic in the interactions between Rampling and Elkand, a pair of actors who are each other's polar opposites in skill level and career path: they're drawing something incredible out of each other, while also providing a striking contrast in screen presence. As a snapshot of an off-kilter but clearly nourishing friendship, their camaraderie is tremendously appealing, and the places that the narrative goes adds a layer of twisted tragedy to this relationship. It's all a little aimless, and a bit hackneyed in the end, but it's watchable enough, even if its primary strengths aren't ones I'd expect to see in a horror anthology.

The last patient, Dr. Byron (Herbert Lom), doesn't have a story, just a strange obsession: he's made little robot replicas of his former colleagues, and he's convinced that he can transfer human souls into these weird dolls, including his own. With that, Martin heads back to Rutherford, and it's here that we discover that this is Byron's story, "Mannikins of Horror", and that his robot scheme is partially about creating a race of tiny assassins to deal with his hated enemy Rutherford. And this is, frankly, pretty rushed and unsatisfying - the best part about it is the way it repurposes the material of the framking narrative, and gives Asylum as a whole such a natural organic shape. And a secondary strength is that it's bringing in Lom (for a whole half-day of work) to lend some of his imperious arrogance to the proceedings, a very welcome addition indeed. But "Mannikins of Horror" doesn't really do anything other than give us a suitably creepy image of a tiny wax Lom carrying a scalpel like a javelin, and it makes it awfully hard to transition back into the resolution to the actual plot - where is the mad Dr. Starr? - when at least one of the candidates turns out to be some kind of actual wizard.

Still, for all that Asylum ends up fizzling to a close (the ending is sort of so unpredictable that it's the most predictable thing), there's enough strong that it still ends up as one of the stronger Amicus portmanteau films regardless. Baker's directing gives a distinct texture to every new phase of the movie, dramatically changing styles between the asylum and each of the three major segments, while also encouraging different kinds of performances from the actors. And the question raised by the set-up gives the whole thing a strong shape that makes this feel like one of the only anthology films I can name that's easier to think of as a complete whole than as the sum total of its individual elements. It's not an example of Amicus at its most perfect, maybe, but it's an unusually good showcase for what the Amicus approach to anthology filmmaking can provide to a movie that it otherwise would lack. It's arguably the studio's most interesting film, I guess I mean to say, and I certainly count "interesting" for a whole lot.

I regret to say that Asylum's individual tales of madness and terror don't end up entirely live up to the pulpy brilliance of that framing narrative, though it would take a whole hell of a lot for them to do so. And the film sort of knows it: the framing narrative is unusually active, so much so that this stretches the very idea of an "anthology" film (or, to use the favored word of Amicus Productions, who created Asylum, a "portmanteau") to the point where it barely feels like it still applies. The conclusion to the third story is given in the framework, and fourth story takes place within the framing narrative, such that it really doesn't make sense to talk about them as separate things. And even without these things, the framework gets an unusual amount of attention, both stylistically and narratively, starting right from its delightfully tongue-in-cheek opening, with Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain storming across the shots of Martin arriving at the asylum, adding a nice note of over-the-top horror movie grumbling (Mussorgsky will return, in the form of Pictures at an Exhibition, and Douglas Gamley's playfully clichéd "original" score echoing the composer's work as well). There's also an odd sense that the stakes of the framework narrative matter more than the stakes of the individual segments: since we're meeting the narrators of those tales, we know that they're not going to die, and they end up not really resolving in any other way; they reach a point of emotional climax and then leap right back to the storyteller looking aghast while Martin ponders their words.

None of this is a complaint! The good news is that Asylum has the filmmaking chops to compensate for the slightly half-baked feeling of its horrifying little anecdotes. Director Roy Ward Baker had a well-honed talent in genre schlock, having made several pictures for Hammer Films prior to this, the first of three movies he directed at Amicus, and he also had some substantial Hollywood credits to his name, including one of the finest of the '50s 3-D movies, Inferno. Though he is almost unquestionably best-known for the British-made 1958 account of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, A Night to Remember, by general acclaim the most artistically and historically successful film on the subject. He was bringing a lot of different skills to Asylum is what I mean to say, and you see them on display in various throughout the whole movie. But he's going overboard in making the titular asylum seem menacing and disorienting, including a hell of a weird POV shot as Martin looks at creepy sketches hanging on the wall, and the camera cranes around in a way suggesting that the young doctor is currently levitating at a 135-degree angle to the floor.

Anyway, Dr. Martin's first visit is to Bonnie (Barbara Perkins) - Rutherford has already nastily mocked him for presuming that Dr. Starr had to be a "him" - and she tells him the story "Frozen Fear": her lover, Walter (Richard Todd), concocted a plan with her to murder his wife Ruth (Sylvia Syms). And this plan involved hiding her body by chopping it into pieces, wrapping them in brown paper, and stashing them in the big coffin freezer in the basement, later to dispose of them bit by bit. And so this he does, coolly offing his wife in a scene that proceeds with the nastiest briskness and lack of any sort of sentiment: Ruth seems nice, outside of her aggressive jealous streak, Walter is a cold-blooded psychopath, and we've got nowhere to go while we watch him chop her down without so much as breaking into a sweat.

Even for a single segment of an anthology film, that's not nearly enough for an actual story, of course, so it's not at all shocking that there's more to it than that. Ruth, as it so happens, has been studying voodoo lately, and she had a protective charm on when she was dumped into the freezer. This has the unexpected effect of resuscitating all of her pieces, which prove to be astonishingly effective at exacting revenge on her killer, though this is much because he's pinned down in amazed terror as anything else. Meanwhile, Bonnie is due to come around to see how her lover has fared in getting rid of the one big roadblock to their happiness, and what she sees will be just the sort of thing that might make you sound like a gibbering maniac who needs to be sent to an insane asylum, if you tried to describe it to the cops.

One of the fascinating things about Asylum is that every one of the segments has notably different strengths and weaknesses, and in this case, there's no mistaking the strength: the sequence in which Ruth's parts crawl out of the freezer to attack Walter is extraordinarily unnerving, one of the most genuinely scary things in any Amicus film. It gets this in large part by plying one of the simplest tricks it could imaginably play: there's hardly any sound other than music after Ruth dies. And so what plays out is a kind of horrible silent ballet of inexplicable movement, with the wrapped body parts (which look creepy as hell even just sitting there) slowly tugged in front of the lens in little jerks along the ground it has a genuinely otherworldly quality, with the kind of horribly inevitability of a dream you can't wake up from, and as much as the film has given us only reasons to despise Walter, it's hard not to share his frozen fear , if you will, at the eerie sight, filmed by Baker and cinematographer Denys Coop in such an unexceptional realistic mode.

There are different strengths and weaknesses in each segment, I said, and "Frozen Fear" also has its downside: while all three of the segments feel more or less incomplete, the other two at least feel like stories. This one really just feels like a sketch, or an anecdote. None of Bonnie, Walter or Ruth have any personality at all, they're just props in a little chain of man kills wife; man dismembers wife; wife's hand kills him. It's only the fact that the horrifying imagery hits so hard that the segment holds any interest at all.

Martin's next subject is Bruno (Barry Morse), a tailor who recalls the bizarre events of his last job in "The Weird Tailor" - a title which is, if nothing, a world-class self-aware pun. Times have been tough, and he ends up facing an ultimatum from his landlord Stebbins (John Franklyn-Robbins) that he cannot possibly hope to meet. Luck apparently comes to him, though, when a very odd and obviously untrustworthy man calling himself Smith (Peter Cushing) comes by with a piece of extraordinary cloth that seems to glow in multiple colors. He also has an extremely specific set of instructions for how that cloth needs to be cut and sewed, too, and while this all spells bad news, or at least a client who is definitely hiding something, Bruno and his wife Anna (Ann Firbank) are in such desperate straits, and the payday promises to be so lucrative, that the tailor decides to overlook the red flags and muscle through the very odd request. This being the kind of film it is, with the title this segment has, it's not at all a surprise when the suit is being used for an eldritch reason - though also a sad one, if Bruno could see that through his terror.

In a pinch, I'd be inclined to call "The Weird Tailor" the highlight of Asylum: it certainly tells the most complete story of any of the segments. At heart, this is a story of two very sad and very desperate people talking past each other, and the horrible results of this miscommunication, and Morse and Cushing do a great job of embodying those elements of the characters. The balance between the two of them, and the panicky misunderstanding that rises when they confront each other over Smith's secret, is so good that the sequence suffers instantly from the fact that this isn't actually the conflict; there's a whole "act" of the story leftover after the tailor flees Smith's chambers, and it feels oddly-motivated, and a little bit like this was quickly revised to add some stronger horror elements than had initially been part of the story. Still, the acting, and the uncomfortable amount of blank empty spaces that fill many of the interiors in this sequence, keep it working; there's an abstract quality that amplifies the horror, making it disquieting if not actively scary.

The next patient, Barbara (Charlotte Rampling) is unnervingly self-aware: she knows about her own mental disturbances, having been in an asylum once before. And the story of what happened after she was released is told in "Lucy Comes to Stay", which like "The Weird Tailor" feels very little like horror, or a genre film at all, for most of its length; when horror comes in, though, it's generally more organic and inevitable than it was there. Barbara, we learn, was under the thumb of her brother George (James Villiers), and the nurse Miss Higgins (Megs Jenkins), whose treatment of her felt awfully peremptory and authoritarian. Happily, her wonderful friend Lucy (Britt Ekland) pops up just then to help keep her spirits up. Lucy is quite a bit less placid than Barbara, and quite a bit more willing to be a thorn in the sides of George and Higgins, and this initially delights Barbara. But eventually, Lucy's antics take on a more vicious streak.

There's more to it still - I mentioned that this was the segment whose narrative resolution actually takes place in the framing story, and that's a big part of why "Lucy Comes to Stay" feels sort of like it doesn't actually have a narrative. Also because it turns out to be awfully trite, once we get that resolution. Still, there's something magnetic in the interactions between Rampling and Elkand, a pair of actors who are each other's polar opposites in skill level and career path: they're drawing something incredible out of each other, while also providing a striking contrast in screen presence. As a snapshot of an off-kilter but clearly nourishing friendship, their camaraderie is tremendously appealing, and the places that the narrative goes adds a layer of twisted tragedy to this relationship. It's all a little aimless, and a bit hackneyed in the end, but it's watchable enough, even if its primary strengths aren't ones I'd expect to see in a horror anthology.

The last patient, Dr. Byron (Herbert Lom), doesn't have a story, just a strange obsession: he's made little robot replicas of his former colleagues, and he's convinced that he can transfer human souls into these weird dolls, including his own. With that, Martin heads back to Rutherford, and it's here that we discover that this is Byron's story, "Mannikins of Horror", and that his robot scheme is partially about creating a race of tiny assassins to deal with his hated enemy Rutherford. And this is, frankly, pretty rushed and unsatisfying - the best part about it is the way it repurposes the material of the framking narrative, and gives Asylum as a whole such a natural organic shape. And a secondary strength is that it's bringing in Lom (for a whole half-day of work) to lend some of his imperious arrogance to the proceedings, a very welcome addition indeed. But "Mannikins of Horror" doesn't really do anything other than give us a suitably creepy image of a tiny wax Lom carrying a scalpel like a javelin, and it makes it awfully hard to transition back into the resolution to the actual plot - where is the mad Dr. Starr? - when at least one of the candidates turns out to be some kind of actual wizard.

Still, for all that Asylum ends up fizzling to a close (the ending is sort of so unpredictable that it's the most predictable thing), there's enough strong that it still ends up as one of the stronger Amicus portmanteau films regardless. Baker's directing gives a distinct texture to every new phase of the movie, dramatically changing styles between the asylum and each of the three major segments, while also encouraging different kinds of performances from the actors. And the question raised by the set-up gives the whole thing a strong shape that makes this feel like one of the only anthology films I can name that's easier to think of as a complete whole than as the sum total of its individual elements. It's not an example of Amicus at its most perfect, maybe, but it's an unusually good showcase for what the Amicus approach to anthology filmmaking can provide to a movie that it otherwise would lack. It's arguably the studio's most interesting film, I guess I mean to say, and I certainly count "interesting" for a whole lot.

Categories: amicus productions, anthology films, british cinema, horror