In the South the war is what AD is elsewhere; they date from it

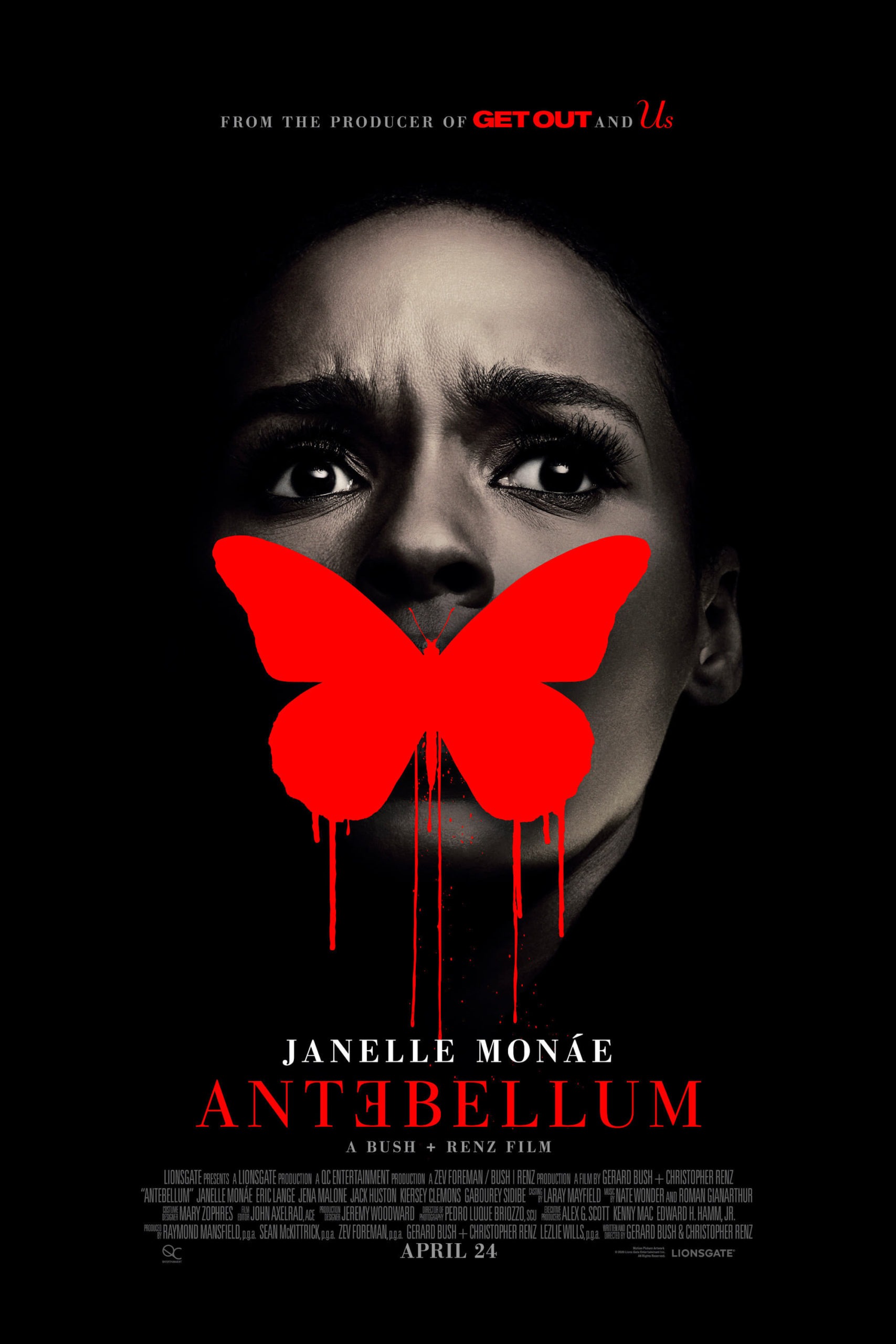

The second-most illuminating fact about Antebellum, a new piece of "elevated horror" that's not all that elevated and is pretty bad as horror, is that it's coming to us, as the ad campaign says, "from the producers of Get Out and Us", which is true if you accept that "the producers" is a shorthand for "some of the producers, but not the ones you've heard of", while also erasing the difference between "producer" and "executive producer". In fact, Sean McKittrick is the only person to have the same role on all three films (Edward H. Hamm, Jr. had a producer credit on Get Out and an EP credit on Antebellum; Raymond Mansfield has the exact reverse; neither man was a producer on Us), and Jordan Peele, the name the ad campaign is hoping you were thinking about, had nothing to do with Antebellum at all. Anyway, the "from the producers of" gambit is one of the surest signs out there that the new movie in question is a blatant ripoff made by people whose job is humping a commercially-viable trend to death, and given that much of Antebellum seems designed to answer the question nobody has ever once asked, "what if Get Out was terrible and sucked?" it capably lives down to this stereotype.

Now, that was the second-most illuminating fact about Antebellum. The most-illuminating fact is one that has been living in the expository boilerplate interviews with the writer-directors, Gerard Bush & Christopher Renz. This is their first feature film, but they've been working together for some time, under the brand name Bush+Renz, running marketing campaigns for social justice issues. To put it bluntly: they're ad men. And with Antebellum, they have made the movie that ad men would make. It is is a film that imagines, and actively wants, a viewer that has no capacity for thought, leading to some of the bluntest, least-sophisticated messaging of any message movie I can recall in quite some time. It communicates in social media aphorisms instead of dialogue and treats its characters as lifestyle brands rather than personalities. It packages its very serious, senstive, and delicate content in a box of the glossiest cinematography imaginable, courtesy of Pedro Luque, giving some hideous, depraved content a plush sheen. It has an aggressive shallowness that would be off-putting no matter what, but is completely horrifying in the particular context that the film gives us.

That context is: the United States' history of chattel slavery. The film opens on a plantation, where Luque's airy, floating camera gives us a pantomimed tour of a slave's life in the fields in a lengthy steadicam tracking shot that immediately robs the material of any real weight and places it securely in the realm of the atmospheric and stylish. Oh, that's one of the other things the film keeps mishandling: tone. This wants to be a horror film, I think; at the very least, Roman GianArthur and Nate wonder's music demands, right from the start, that we think of this in those terms, with its threatening minor-key melodies and haunted house string section. And since the music is probably the only thing that unabashedly works in the movie, it tends to overwhelm everything else. So atmospheric, scary horror it is, but the film isn't really "doing" horror, it's more of a character drama (which is tough to do with characters who have been written this badly). So on the one hand, the aesthetics, visually and sonically, say "ooh, how creepy", while the writing says "this is a serious message movie", and the acting says, well, the acting is too busy trying to cope with the writing to say much of anything. Anyway, making a horror message movie takes a special alchemy, and Antebellum fucks it up; it would so clearly be better (though I imagine, not actively "good") if it simply dropped the pretense to genre at all.

Anyway, on the plantation, a runaway slave, Eden (Janelle Monáe) has just been caught and brought back, right around the time that a new slave (Kiersey Clemons), having just been assigned the name Julia, arrives. The Civil War is apparently going well for the Confederacy at the moment, and the smug way the slave drivers rub this in has lead to increasing discontent; indeed, it seems that a full-on slave rebellion is about the break out. But Eden, grim-faced and silent, seems quite disinterested in joining Julia or Eli (Tongayi Charisa) in planning an escape attempt. And as this plays out - or doesn't more like - the film subjects us to the various torture and violence perpetrated by the guards on their captives. We're not even really into the meat of why the film is so jaw-droppingly bad yet, but already things are going horribly awry: the film is playing with some of the most charged imagery it's possible to play with, and treating it with the vigor of, well, a cheap horror film, preferring to wallop us with shocking content more for the sake of the shocks than doing anything with it. Again, this is the work of advertising whizzes who are certainly better at pushing buttons than triggering some kind of intellectual engagement with this most difficult material (for the record, Bush is African-American, Renz is white).

About a third of the way through, the film does one of the only cool things it will ever do stylistically: waking up Eden with a ringing cellphone. Except it turns out to be a soundbridge over to the 21st Century, where we meet Veronica (Monáe), a famous talking head and the author of some popular sociology books, who has recently been making waves with some vociferous anti-racist arguments. We get a terrific example of how little Antebellum cares about arguing its points rather than simply squawking "racism is very bad and so is slavery" when we see Veronica on a generic news program opposite a puffy old white guy (Bernard Hocke); both of them spout out what amounts to nonsense syllables that refer to nothing at all but the broadest culture war bromides, and it's clear that the movie believes that we'll agree that we just saw her win a thrilling rhetorical battle. Anyway, shortly before heading into the Southern U.S. for a seminar, Veronica takes a video call from a woman named Elizabeth (Jena Malone), who claims to have some kind of business proposition, but really just wants to make passive-aggressive racist insults. Malone, by the way, is either the best or worst member of the cast: while most people, like Monáe and Gabourey Sidibe as Veronica's friend, are mostly just trying to find a way to motivate their characters' arbitrary behavior and finding ways of phrasing the clichés they're reciting as though they're actually original thoughts, Malone has decided to play her mustache-twirling villainous racist as camp, glomming onto a purring Southern accent and grinning with malicious hunger as she stares her snakelike stare at Veronica. It's gaudy and hilarious in the wrong ways, but it's also one of only two things about Antebellum I expect to remember very far down the line.

The other thing is the complete hash the movie makes of its own narrative. I'm not going to tell you what happens, or how the Civil War timeline and Veronica's adventures as a seminar leader end up communicating with each other, though I don't know why I should bother with such niceties; the plot twist tying this together is so predictable that my first thought was "no way would they actually do that", followed, after a few minutes, by "they for sure would do that", once I realised how allergic Antebellum was going to be to original thoughts or aesthetic dignity. Suffice it to say that in their anxious desire to give us a big surprise, Bush+Renz have rendered their argument incoherent, incapable of any more nuance than the most blunt-force "racism bad" message. And they've also gutted their story; the revelations of the last third make it quite impossible to parse what the hell is going on with a single one of the characters in the first third, who could not possibly behave the way we saw them behave, unless they knew that they were the pawns of a movie with a humiliatingly superficial metaphor about racism in America as its primary narrative engine. And it also simply doesn't make sense: there are implications to how the world must work for this story to work that the writers cannot possibly have thought through. Or worse, they did think it through, and thought it was clever. I was prepared from fairly early to write this off as a bad movie made in bad taste and with questionable morals; the last third upgrades (downgrades?) that to a transfixing boondoggle that has treated slavery at a level of tacky exploitation that we haven't seen since the '70s.

Now, that was the second-most illuminating fact about Antebellum. The most-illuminating fact is one that has been living in the expository boilerplate interviews with the writer-directors, Gerard Bush & Christopher Renz. This is their first feature film, but they've been working together for some time, under the brand name Bush+Renz, running marketing campaigns for social justice issues. To put it bluntly: they're ad men. And with Antebellum, they have made the movie that ad men would make. It is is a film that imagines, and actively wants, a viewer that has no capacity for thought, leading to some of the bluntest, least-sophisticated messaging of any message movie I can recall in quite some time. It communicates in social media aphorisms instead of dialogue and treats its characters as lifestyle brands rather than personalities. It packages its very serious, senstive, and delicate content in a box of the glossiest cinematography imaginable, courtesy of Pedro Luque, giving some hideous, depraved content a plush sheen. It has an aggressive shallowness that would be off-putting no matter what, but is completely horrifying in the particular context that the film gives us.

That context is: the United States' history of chattel slavery. The film opens on a plantation, where Luque's airy, floating camera gives us a pantomimed tour of a slave's life in the fields in a lengthy steadicam tracking shot that immediately robs the material of any real weight and places it securely in the realm of the atmospheric and stylish. Oh, that's one of the other things the film keeps mishandling: tone. This wants to be a horror film, I think; at the very least, Roman GianArthur and Nate wonder's music demands, right from the start, that we think of this in those terms, with its threatening minor-key melodies and haunted house string section. And since the music is probably the only thing that unabashedly works in the movie, it tends to overwhelm everything else. So atmospheric, scary horror it is, but the film isn't really "doing" horror, it's more of a character drama (which is tough to do with characters who have been written this badly). So on the one hand, the aesthetics, visually and sonically, say "ooh, how creepy", while the writing says "this is a serious message movie", and the acting says, well, the acting is too busy trying to cope with the writing to say much of anything. Anyway, making a horror message movie takes a special alchemy, and Antebellum fucks it up; it would so clearly be better (though I imagine, not actively "good") if it simply dropped the pretense to genre at all.

Anyway, on the plantation, a runaway slave, Eden (Janelle Monáe) has just been caught and brought back, right around the time that a new slave (Kiersey Clemons), having just been assigned the name Julia, arrives. The Civil War is apparently going well for the Confederacy at the moment, and the smug way the slave drivers rub this in has lead to increasing discontent; indeed, it seems that a full-on slave rebellion is about the break out. But Eden, grim-faced and silent, seems quite disinterested in joining Julia or Eli (Tongayi Charisa) in planning an escape attempt. And as this plays out - or doesn't more like - the film subjects us to the various torture and violence perpetrated by the guards on their captives. We're not even really into the meat of why the film is so jaw-droppingly bad yet, but already things are going horribly awry: the film is playing with some of the most charged imagery it's possible to play with, and treating it with the vigor of, well, a cheap horror film, preferring to wallop us with shocking content more for the sake of the shocks than doing anything with it. Again, this is the work of advertising whizzes who are certainly better at pushing buttons than triggering some kind of intellectual engagement with this most difficult material (for the record, Bush is African-American, Renz is white).

About a third of the way through, the film does one of the only cool things it will ever do stylistically: waking up Eden with a ringing cellphone. Except it turns out to be a soundbridge over to the 21st Century, where we meet Veronica (Monáe), a famous talking head and the author of some popular sociology books, who has recently been making waves with some vociferous anti-racist arguments. We get a terrific example of how little Antebellum cares about arguing its points rather than simply squawking "racism is very bad and so is slavery" when we see Veronica on a generic news program opposite a puffy old white guy (Bernard Hocke); both of them spout out what amounts to nonsense syllables that refer to nothing at all but the broadest culture war bromides, and it's clear that the movie believes that we'll agree that we just saw her win a thrilling rhetorical battle. Anyway, shortly before heading into the Southern U.S. for a seminar, Veronica takes a video call from a woman named Elizabeth (Jena Malone), who claims to have some kind of business proposition, but really just wants to make passive-aggressive racist insults. Malone, by the way, is either the best or worst member of the cast: while most people, like Monáe and Gabourey Sidibe as Veronica's friend, are mostly just trying to find a way to motivate their characters' arbitrary behavior and finding ways of phrasing the clichés they're reciting as though they're actually original thoughts, Malone has decided to play her mustache-twirling villainous racist as camp, glomming onto a purring Southern accent and grinning with malicious hunger as she stares her snakelike stare at Veronica. It's gaudy and hilarious in the wrong ways, but it's also one of only two things about Antebellum I expect to remember very far down the line.

The other thing is the complete hash the movie makes of its own narrative. I'm not going to tell you what happens, or how the Civil War timeline and Veronica's adventures as a seminar leader end up communicating with each other, though I don't know why I should bother with such niceties; the plot twist tying this together is so predictable that my first thought was "no way would they actually do that", followed, after a few minutes, by "they for sure would do that", once I realised how allergic Antebellum was going to be to original thoughts or aesthetic dignity. Suffice it to say that in their anxious desire to give us a big surprise, Bush+Renz have rendered their argument incoherent, incapable of any more nuance than the most blunt-force "racism bad" message. And they've also gutted their story; the revelations of the last third make it quite impossible to parse what the hell is going on with a single one of the characters in the first third, who could not possibly behave the way we saw them behave, unless they knew that they were the pawns of a movie with a humiliatingly superficial metaphor about racism in America as its primary narrative engine. And it also simply doesn't make sense: there are implications to how the world must work for this story to work that the writers cannot possibly have thought through. Or worse, they did think it through, and thought it was clever. I was prepared from fairly early to write this off as a bad movie made in bad taste and with questionable morals; the last third upgrades (downgrades?) that to a transfixing boondoggle that has treated slavery at a level of tacky exploitation that we haven't seen since the '70s.