Australian Winter of Blood: Alice doesn't live here anymore

I hope I will not devalue Lake Mungo if I describe it as a film that feels absolutely perfect for 2008. That suggests, I am afraid, that it has very little to offer for those of us living later than 2008, and this is not at all the case. But I think the film would have been inconceivable not that many years earlier, and it would have been poorly-made not that many years later. So: absolutely perfect for 2008.

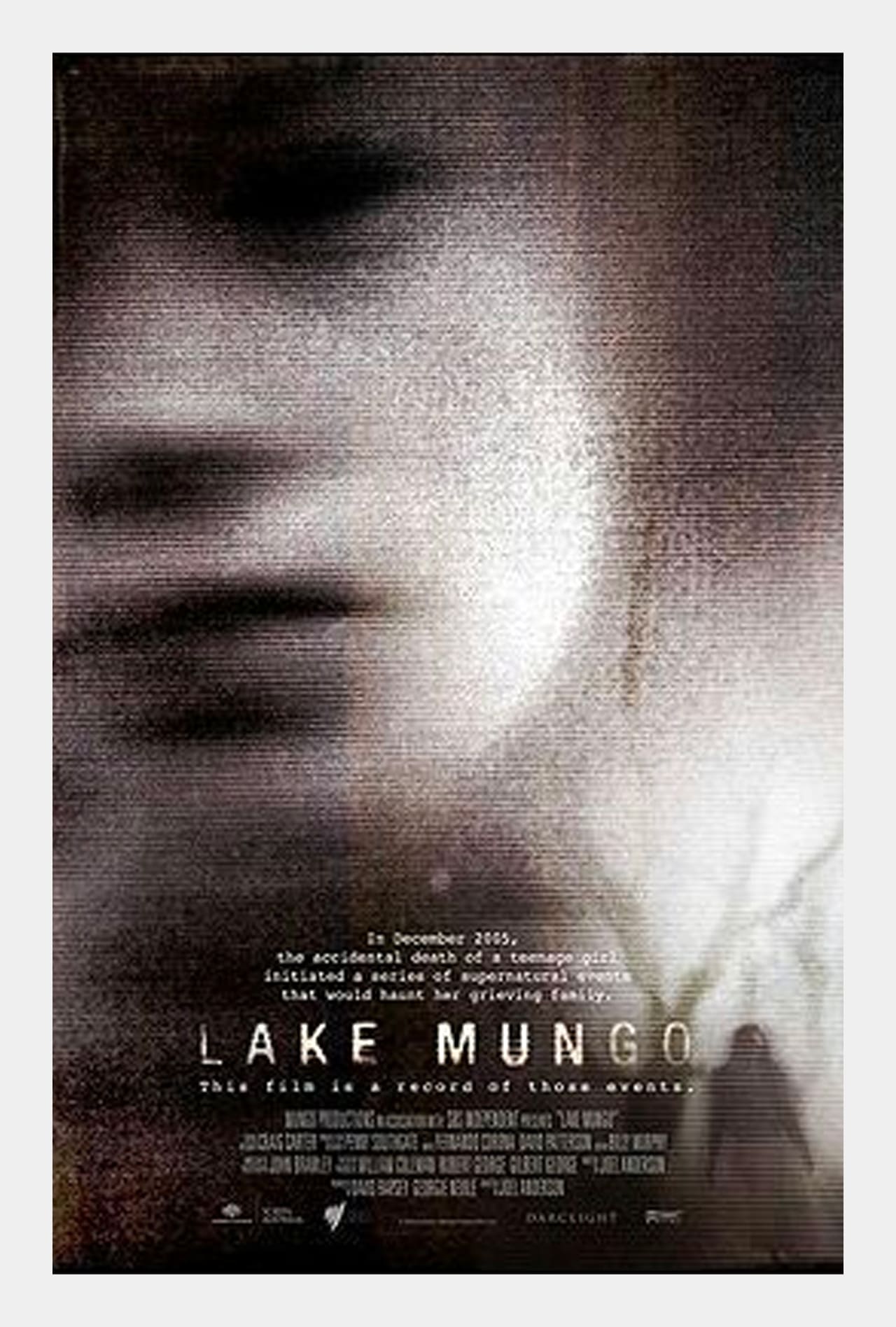

The biggest reason for this is that Lake Mungo is a mockumentary, telling us the horrible true story of the Palmer family and the tragedy that visited them in 2005. Or the "true" story, at any rate. The film exists in this form because writer-director Joel Anderson had found that the script he wrote to be his feature debut was going to be prohibitively expensive to shoot, and so he wrote a different script that he could finance. For the documentary form gave him leeway to tell, not show, to place the actors in one location each, and to generally cut costs on anything that could be plausibly defended as "this is how they make cheap documentaries" (David Paerson's musical score is the biggest beneficiary of this, relying on trite horror music clichés and a distinctly tinny and small-sounding synthetic orchestration; in context, it feels like the exact music a cheap little haunting documentary would get, and so it helps to bolster the illusion that we're watching something real).

The reason I consider this aspect of Lake Mungo to be so quintessentially 2008-ian is that 2008 was the year that found-footage horror hit the world in a big way. Anderson wrote the first draft in 2005, long before Cloverfield came along to light the fuse on that particular fad, but there are all kind of affinities between this film and those. This is largely because they're trying to solve the same problem: what can you do to the footage to sell the audience on it being a bit cheap-looking and artless. Pretend that it's raw footage, pretend that it's a low-rent doc; it's all kind of the same thing, foregrounding the fact that we're looking at a media file rather than pretending it's a polished Real Movie. If Lake Mungo had come out all that much later, I find myself wondering if it would have just gone the found footage route. It would have certainly been a lesser project if that's the case - the documentary structure turns the whole thing into a kind of memoir, with the characters reflecting on events in their lives rather than just experiencing them.

And this is very much part of what makes Lake Mungo such an engaging film. It's a ghost story, by genre, but it's also a story about the grieving process and the way that a family can't figure out how to deal with a shocking loss. 16-year-old Alice Palmer (Talia Zucker) has already died when the movie starts; she drowned on a family trip (which was not at Lake Mungo, and this at least initially confused me), and now exists only as a memory and a face in old photos and videos. Also possibly as a ghost haunting her family. We meet her parents, June (Rosie Traynor) and Russell (David Pledger), and her brother Matthew (Martin Sharpe), and they don't immediately share this information, speaking more generally about their sadness around losing Alice and not knowing what to do with themselves, but the way the film has already framed things, it's no surprise when they mention the apparently paranormal events happening - Matthew has set up cameras, and if you squint, it seems like there might be a human figure in some of his images, and if you squint even harder, it seems like it might be Alice.

The film treats this with an unimaginably sophisticated touch: it is both very creepy, and very tender towards the surviving Palmers (incidentally, given the plot set-up and some of the specific details, the family name seems purposefully designed to point us towards Twin Peaks. But despite the overlap, this is mostly doing its own thing). They talk about their very strange situation with a curious lack of affect that is not entirely indistinguishable from flat performances. But the more we go into the film, the less it feels like low-budget acting by low-budget actors, the more it seems like the Palmers themselves are just plain ambivalent - definitely not scared, at any rate, and one suspects that for June, in particular, we're watching a woman who hoped she was being haunted by her daughter. This all draws from the fact that we're meeting these people after the story is over, though we learn what happened in order, over the course of the film's gentle but persistently forward-moving 87 minutes: they have already processed all the things we're going to hear about, and we're watching the end result of all the emotions that ordinarily take place in a ghost story, without seeing them before our eyes. It's a surprising and surprisingly effective way to approach things, and it firmly repositions the focus of Lake Mungo from a scary story about a ghost popping up in the corner of frames, to a psychological study of a grieving family dealing with their grief in a particularly novel way.

This isn't to say that the film isn't also a good spooky ghost story. To go into the details would be to spoil the fun - let us just say that there is a pretty nifty twist that the movie doesn't go out of its way to emphasise, shifting the film from "there may be a ghost" to... well, right back to "there may be a ghost", but coming at it from a different direction. And as the film develops, Alice-if-it-really-is-she starts to develop as a fascinating character in her own right, who goes through her own reckoning with death in a way that itself helps her grieving family go through theirs. It's complicated, but not when you're watching it.

Anyway, that paragraph was meant to be about how Lake Mungo is actually good as a horror film, and failed. So let me try again. The film has very little in the way of actual scares, but it has a hell of a lot in the way of innuendo and suggestion, and its implications can be very freaky, if you're willing to do the work of meeting the film on its own terms. The story that reveals itself over the course of the Palmer's recollections is basically a long line of uncanny coincidences along the permeable line between the normal and the paranormal; visions of corpses, sudden flashes of horrible insight, stumbling over the answer to mysteries you didn't know had been posed. The overall impression I get is of another quintessentially 2008 pop culture relic, the "creepypasta" ghost stories that wandered their way around the internet mostly between 2007 and the early 2010s, giving a modern gloss to the material of old urban legends; Lake Mungo's tone of reportage and memoir in particular give it that feeling, just as much as the kinds of low-key, more-unnerving-and-moody-than-scary scares that Anderson lays out for us do.

In short, we have a very thoughtful story about the human side of a traditional ghost story that still takes the time to put a clammy autumnal chill in our bones, and does it in the form of one of the most convincing and conceptually-sound horror mockumentaries I have ever seen. It is an intellecually satisfying, emotionally engaging little ghost story, packaged to look like some tawdry episode of a ghost-hunting reality series; I frankly loved it a little bit, and the fact that I stumbled across it largely by accident* is horribly upsetting; it feels like horror fans the world over should be celebrating this as one of that genre's smartest and most innovative films of the 2000s. Because that, frankly, is exactly what it is.

Body Count: Technically 0, though we do see a bloated corpse.

*The logic went, in its entirety: "oh, Australia had an early found-footage horror movie? I should see how they handled it". They handled it immensely well, so much that I'm wondering if I need to come up with a theory of Australian Horror Is Better, akin to my theory of Canadian Horror Is Better.

And it's anyway never presented for even a minute like "found footage" - it's more like if the people directing The Blair Witch Project hadn't died in the woods, and we were watching Heather Donahue's final cut the whole time.

The biggest reason for this is that Lake Mungo is a mockumentary, telling us the horrible true story of the Palmer family and the tragedy that visited them in 2005. Or the "true" story, at any rate. The film exists in this form because writer-director Joel Anderson had found that the script he wrote to be his feature debut was going to be prohibitively expensive to shoot, and so he wrote a different script that he could finance. For the documentary form gave him leeway to tell, not show, to place the actors in one location each, and to generally cut costs on anything that could be plausibly defended as "this is how they make cheap documentaries" (David Paerson's musical score is the biggest beneficiary of this, relying on trite horror music clichés and a distinctly tinny and small-sounding synthetic orchestration; in context, it feels like the exact music a cheap little haunting documentary would get, and so it helps to bolster the illusion that we're watching something real).

The reason I consider this aspect of Lake Mungo to be so quintessentially 2008-ian is that 2008 was the year that found-footage horror hit the world in a big way. Anderson wrote the first draft in 2005, long before Cloverfield came along to light the fuse on that particular fad, but there are all kind of affinities between this film and those. This is largely because they're trying to solve the same problem: what can you do to the footage to sell the audience on it being a bit cheap-looking and artless. Pretend that it's raw footage, pretend that it's a low-rent doc; it's all kind of the same thing, foregrounding the fact that we're looking at a media file rather than pretending it's a polished Real Movie. If Lake Mungo had come out all that much later, I find myself wondering if it would have just gone the found footage route. It would have certainly been a lesser project if that's the case - the documentary structure turns the whole thing into a kind of memoir, with the characters reflecting on events in their lives rather than just experiencing them.

And this is very much part of what makes Lake Mungo such an engaging film. It's a ghost story, by genre, but it's also a story about the grieving process and the way that a family can't figure out how to deal with a shocking loss. 16-year-old Alice Palmer (Talia Zucker) has already died when the movie starts; she drowned on a family trip (which was not at Lake Mungo, and this at least initially confused me), and now exists only as a memory and a face in old photos and videos. Also possibly as a ghost haunting her family. We meet her parents, June (Rosie Traynor) and Russell (David Pledger), and her brother Matthew (Martin Sharpe), and they don't immediately share this information, speaking more generally about their sadness around losing Alice and not knowing what to do with themselves, but the way the film has already framed things, it's no surprise when they mention the apparently paranormal events happening - Matthew has set up cameras, and if you squint, it seems like there might be a human figure in some of his images, and if you squint even harder, it seems like it might be Alice.

The film treats this with an unimaginably sophisticated touch: it is both very creepy, and very tender towards the surviving Palmers (incidentally, given the plot set-up and some of the specific details, the family name seems purposefully designed to point us towards Twin Peaks. But despite the overlap, this is mostly doing its own thing). They talk about their very strange situation with a curious lack of affect that is not entirely indistinguishable from flat performances. But the more we go into the film, the less it feels like low-budget acting by low-budget actors, the more it seems like the Palmers themselves are just plain ambivalent - definitely not scared, at any rate, and one suspects that for June, in particular, we're watching a woman who hoped she was being haunted by her daughter. This all draws from the fact that we're meeting these people after the story is over, though we learn what happened in order, over the course of the film's gentle but persistently forward-moving 87 minutes: they have already processed all the things we're going to hear about, and we're watching the end result of all the emotions that ordinarily take place in a ghost story, without seeing them before our eyes. It's a surprising and surprisingly effective way to approach things, and it firmly repositions the focus of Lake Mungo from a scary story about a ghost popping up in the corner of frames, to a psychological study of a grieving family dealing with their grief in a particularly novel way.

This isn't to say that the film isn't also a good spooky ghost story. To go into the details would be to spoil the fun - let us just say that there is a pretty nifty twist that the movie doesn't go out of its way to emphasise, shifting the film from "there may be a ghost" to... well, right back to "there may be a ghost", but coming at it from a different direction. And as the film develops, Alice-if-it-really-is-she starts to develop as a fascinating character in her own right, who goes through her own reckoning with death in a way that itself helps her grieving family go through theirs. It's complicated, but not when you're watching it.

Anyway, that paragraph was meant to be about how Lake Mungo is actually good as a horror film, and failed. So let me try again. The film has very little in the way of actual scares, but it has a hell of a lot in the way of innuendo and suggestion, and its implications can be very freaky, if you're willing to do the work of meeting the film on its own terms. The story that reveals itself over the course of the Palmer's recollections is basically a long line of uncanny coincidences along the permeable line between the normal and the paranormal; visions of corpses, sudden flashes of horrible insight, stumbling over the answer to mysteries you didn't know had been posed. The overall impression I get is of another quintessentially 2008 pop culture relic, the "creepypasta" ghost stories that wandered their way around the internet mostly between 2007 and the early 2010s, giving a modern gloss to the material of old urban legends; Lake Mungo's tone of reportage and memoir in particular give it that feeling, just as much as the kinds of low-key, more-unnerving-and-moody-than-scary scares that Anderson lays out for us do.

In short, we have a very thoughtful story about the human side of a traditional ghost story that still takes the time to put a clammy autumnal chill in our bones, and does it in the form of one of the most convincing and conceptually-sound horror mockumentaries I have ever seen. It is an intellecually satisfying, emotionally engaging little ghost story, packaged to look like some tawdry episode of a ghost-hunting reality series; I frankly loved it a little bit, and the fact that I stumbled across it largely by accident* is horribly upsetting; it feels like horror fans the world over should be celebrating this as one of that genre's smartest and most innovative films of the 2000s. Because that, frankly, is exactly what it is.

Body Count: Technically 0, though we do see a bloated corpse.

*The logic went, in its entirety: "oh, Australia had an early found-footage horror movie? I should see how they handled it". They handled it immensely well, so much that I'm wondering if I need to come up with a theory of Australian Horror Is Better, akin to my theory of Canadian Horror Is Better.

And it's anyway never presented for even a minute like "found footage" - it's more like if the people directing The Blair Witch Project hadn't died in the woods, and we were watching Heather Donahue's final cut the whole time.