The king is dead

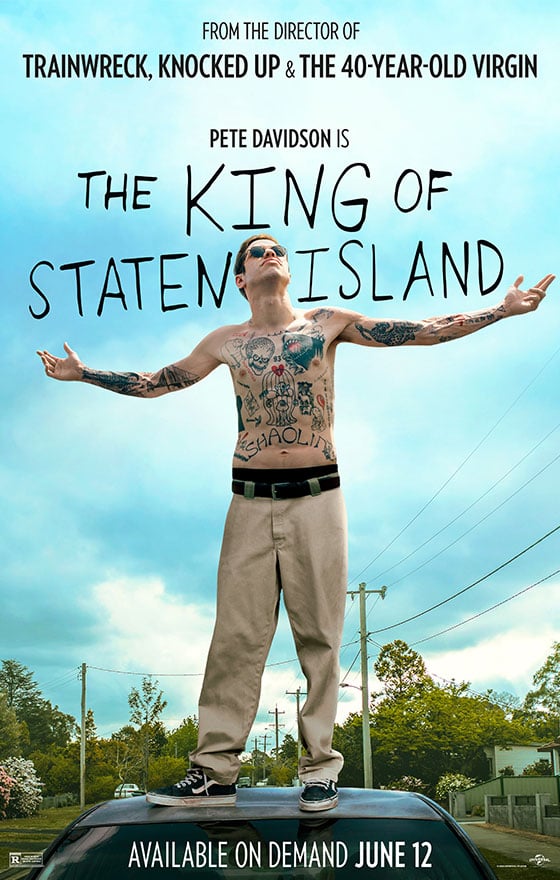

Pete Davidson is a prickly, sad, and a tough person to be around. The reason I know this is that Davidson's entire professional identity is built around defining himself as prickly, sad, and tough to be around. And now we have him as the lead actor in an entire semi-autobiographical feature film that he co-wrote, with Judd Apatow & Dave Sirus, The King of Staten Island, for him to be prickly, sad, and tough to be around for 136 whole minutes. Because Apatow directed the film as well, and if there's one thing you can count on from a film directed by Judd Apatow, it's that it will be a whole hell of a lot longer than there is any earthly reason for it to be, and longer than it comes at all close to justifying.

So here's question number one: do we want this to happen? This is two and a quarter hours of spending time with a character whose defining characteristic is that it's difficult to want to spend any time with him at all, and I will say with all apologies to Davidson, whose life seems to have been fairly difficult, the film succeeds at making me not want that. The film's very leisurely narrative generally takes the form that Scott Carlin, the Davidson analogue, is abrasive to everyone around him, and they either do or don't put up with his bullshit on a scene-by-scene basis. As the film progresses, more and more of these scenes end up at "don't", at which point Scott starts to make decisions that involve taking more responsibility and not letting his depression and drug habit serve as the crutches that keep him hiding away from the world in his childhood home.

Davidson has described this as a kind of "what-if?" autobiography, the story of what his life might have been like if he didn't take the first tiny swerve that led to a stand-up career and a position on Saturday Night Live: he and Scott have the same diseases, affection for tattoos, and both are the sons of firefighters who died tragically (Scott's situation is less florid: his dad just died in a regular fire, while Davidson's died in the World Trade Center on 11 September, 2001). That this speculated alternate-universe version of Davidson might have had a path through life identical to the most generic possible version of a stock Apatow protagonist seems awfully convenient; it lets the director sleepwalk though the most shallow version yet of his stock scenario, in which a pothead manchild hangs out with amicable friends presented as a playfully upbeat slacker chorus in a tone that doesn't match the screenplay's need for us to understand that they're a big part of what's holding him back, and manages at great, great length to become no less of a pothead nor any less of manchild, though he is now the version of those things that can hold down a job.

It's a scenario that has gotten a little bit more irritating every time that Apatow has either directed or produced a variation on the theme (I have not seen his last directorial effort, 2015's Trainwreck, which switches things up by making the manchild a woman), and The King of Staten Island an exceptionally shallow version of this character arc. Scott changes in only very small ways, and getting back into the good graces of his on-again, off-again girlfriend (Bel Powley), his mom (Marisa Tomei), and her new boyfriend (Bill Burr) is less about demonstrating his real willingness to change, more about biding his time until they've forgotten about his fuckup behavior. That's probably a little ungenerous, but he certainly doesn't have to make particularly difficult or deep changes to his behavior to get us to the not-especially uplifting scene; the film relies on the ancient trick of showing him being unpleasant to children, and then being kind to the same children, and calling that good enough.

This is, of course, all to be forgiven on the grounds that this is a shaggy, loose, improvised hang-out comedy, and like in every Apatow picture, the feeling that entire scenes are just the actors bouncing ideas off each other without having any idea where they're going is palpable. Also like in every Apatow picture, this results in a tremendous amount of unproductive footage - I have mentioned the 136-minute running time, but I will mention it again, because it's extremely important. This isn't Apatow's longest movie - 2009's Funny People is ten minutes longer - and it's arguably not even his most aggressively shapless: 2012's This Is 40 is preposterously free of structure. But it's his film where the time spent watching people hanging out, getting high, and bantering feels the most dreary and alienating, maybe because we're just getting farther and farther from Apatow's own experiences as he gets older and his ragged young men stay the same age; perhaps because this film notably lacks the ace comic ringers who are usually on hand to make sure his improv sessions are focused on something. The only part of the film that I found especially funny at all was the late appearance of rapper Action Johnson as a beatifically stoned stabbing and/or shooting victim, waxing moodily philosophical on his situation with a dizzying form of ludicrous, absurdist logic that feels like consciously worked-out, constructed humor in a way that nothing else in the film does.

The movie has three committed performances in the form of Tomei, Burr, and Powley, and it seems very likely that a movie focused more on their exasperation with Scott than his wounded puppy guilt and sadness at exasperating them could have had more to it. These are the active characters in the film, taking steps to maneuver around the giant boulder that is Scott; all three actors do something to express how his presence affects their lives and moods, though Burr is the only one doing this in a way that especially scans as "funny". But they're all just there to create conflicts for Scott to deal with, sequentially, in the last 30 minutes or so of the film. Otherwise, it's just watching him be confused and self-loathing and excessively off-putting for endless minute upon minute.

What interest there is in the film never coalesces around Scott, who remains deeply irritating; it is, at best, a worthwhile snapshot of a kind of particular cultural niche and physical space that get swallowed up in pop culture by the rest of New York City, and even New Jersey. Nothing about the film's visuals demand a talent like cinematographer Robert Elswit, but he ably records Staten island in appealingly raw 35mm, with a naturalistic eye for how light filters through the tree-lined streets and bounces off the water. One gets a sense of location, and from that location, one can make broad guesses at the kind of people who live there; it's a bit annoying that we don't get more of that from the script, but at least it's not as utterly banal-looking as most modern American comedies.

So here's question number one: do we want this to happen? This is two and a quarter hours of spending time with a character whose defining characteristic is that it's difficult to want to spend any time with him at all, and I will say with all apologies to Davidson, whose life seems to have been fairly difficult, the film succeeds at making me not want that. The film's very leisurely narrative generally takes the form that Scott Carlin, the Davidson analogue, is abrasive to everyone around him, and they either do or don't put up with his bullshit on a scene-by-scene basis. As the film progresses, more and more of these scenes end up at "don't", at which point Scott starts to make decisions that involve taking more responsibility and not letting his depression and drug habit serve as the crutches that keep him hiding away from the world in his childhood home.

Davidson has described this as a kind of "what-if?" autobiography, the story of what his life might have been like if he didn't take the first tiny swerve that led to a stand-up career and a position on Saturday Night Live: he and Scott have the same diseases, affection for tattoos, and both are the sons of firefighters who died tragically (Scott's situation is less florid: his dad just died in a regular fire, while Davidson's died in the World Trade Center on 11 September, 2001). That this speculated alternate-universe version of Davidson might have had a path through life identical to the most generic possible version of a stock Apatow protagonist seems awfully convenient; it lets the director sleepwalk though the most shallow version yet of his stock scenario, in which a pothead manchild hangs out with amicable friends presented as a playfully upbeat slacker chorus in a tone that doesn't match the screenplay's need for us to understand that they're a big part of what's holding him back, and manages at great, great length to become no less of a pothead nor any less of manchild, though he is now the version of those things that can hold down a job.

It's a scenario that has gotten a little bit more irritating every time that Apatow has either directed or produced a variation on the theme (I have not seen his last directorial effort, 2015's Trainwreck, which switches things up by making the manchild a woman), and The King of Staten Island an exceptionally shallow version of this character arc. Scott changes in only very small ways, and getting back into the good graces of his on-again, off-again girlfriend (Bel Powley), his mom (Marisa Tomei), and her new boyfriend (Bill Burr) is less about demonstrating his real willingness to change, more about biding his time until they've forgotten about his fuckup behavior. That's probably a little ungenerous, but he certainly doesn't have to make particularly difficult or deep changes to his behavior to get us to the not-especially uplifting scene; the film relies on the ancient trick of showing him being unpleasant to children, and then being kind to the same children, and calling that good enough.

This is, of course, all to be forgiven on the grounds that this is a shaggy, loose, improvised hang-out comedy, and like in every Apatow picture, the feeling that entire scenes are just the actors bouncing ideas off each other without having any idea where they're going is palpable. Also like in every Apatow picture, this results in a tremendous amount of unproductive footage - I have mentioned the 136-minute running time, but I will mention it again, because it's extremely important. This isn't Apatow's longest movie - 2009's Funny People is ten minutes longer - and it's arguably not even his most aggressively shapless: 2012's This Is 40 is preposterously free of structure. But it's his film where the time spent watching people hanging out, getting high, and bantering feels the most dreary and alienating, maybe because we're just getting farther and farther from Apatow's own experiences as he gets older and his ragged young men stay the same age; perhaps because this film notably lacks the ace comic ringers who are usually on hand to make sure his improv sessions are focused on something. The only part of the film that I found especially funny at all was the late appearance of rapper Action Johnson as a beatifically stoned stabbing and/or shooting victim, waxing moodily philosophical on his situation with a dizzying form of ludicrous, absurdist logic that feels like consciously worked-out, constructed humor in a way that nothing else in the film does.

The movie has three committed performances in the form of Tomei, Burr, and Powley, and it seems very likely that a movie focused more on their exasperation with Scott than his wounded puppy guilt and sadness at exasperating them could have had more to it. These are the active characters in the film, taking steps to maneuver around the giant boulder that is Scott; all three actors do something to express how his presence affects their lives and moods, though Burr is the only one doing this in a way that especially scans as "funny". But they're all just there to create conflicts for Scott to deal with, sequentially, in the last 30 minutes or so of the film. Otherwise, it's just watching him be confused and self-loathing and excessively off-putting for endless minute upon minute.

What interest there is in the film never coalesces around Scott, who remains deeply irritating; it is, at best, a worthwhile snapshot of a kind of particular cultural niche and physical space that get swallowed up in pop culture by the rest of New York City, and even New Jersey. Nothing about the film's visuals demand a talent like cinematographer Robert Elswit, but he ably records Staten island in appealingly raw 35mm, with a naturalistic eye for how light filters through the tree-lined streets and bounces off the water. One gets a sense of location, and from that location, one can make broad guesses at the kind of people who live there; it's a bit annoying that we don't get more of that from the script, but at least it's not as utterly banal-looking as most modern American comedies.