Suit the action to the word, the word to the action

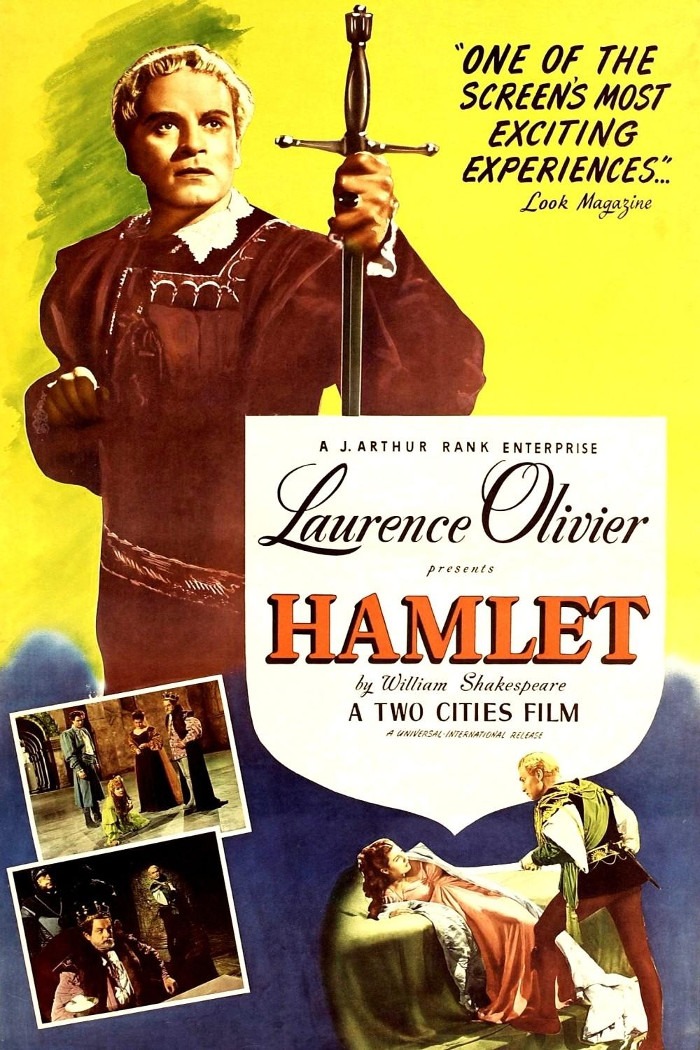

One would be hard-pressed to overstate the importance of director-producer-writer-star Laurence Olivier's 1948 film of Hamlet in the history of screen adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. It's not necessarily a question of direct influence: despite the film's commercial success and sizable haul of awards (both the Golden Lion and the Best Picture Oscar, a combination that would not be seen again until The Shape of Water, 69 years later), it didn't do much to convince producers that filming Shakespeare might be a good financial bet. But this does represent a model of conceiving of the whole business of "Shakespeare on film" as a primarily cinematic endeavor, using the play as a means of getting at a good motion picture rather than clearing the runway for the text with a few movie-like touches around the edges. This approach was and remains uncommon, and it's not in and of itself, a mark of quality; Olivier's own Henry V from 1944 is certainly closer to the "just stage the play" approach than his Hamlet, and I prefer that film to this one in most of the ways that the films can be compared. Still, Shakespeare movies are prone to a certain self-conscious airlessness, and between Olivier's Hamlet and Orson Welles's Macbeth, 1948 was an exciting year for filmmakers attempting to combat by using their respective plays as launching points rather than prisons. And I believe this to be true even though both film have some pretty unmissable problems.

Olivier's approach to preparing Hamlet for the screen started by mercilessly chopping material out: he removed the characters of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern entirely, and left no trace of Denmark's impending war. These changes, especially the former, have led to plenty of criticism in the years since the film premiered, but for myself, I'm all for it. The "full" version of Hamlet is (pace Kenneth Branagh) unreasonably long and was almost certainly not performed as such during Shakespeare's lifetime; considerable slicing must be done to make it a dramatically manageable object, and that slicing must be done judiciously and purposefully. I have my ups and downs with Olivier, but I'd never deny that the man knew Shakespeare, and had put a great deal of thought into what this particular play can be made to do to an audience. His choices all line up, moving the text towards a very distinct and coherent end; this is not just an edited Hamlet, it is a thoughtfully and carefully curated Hamlet.

It is, to be honest, not curated in the ways I would myself have preferred. Hamlet is a deeply ambivalent play and Hamlet himself an ambivalent character, the most complicated and at times vague figure in Shakespeare (which puts him in the running for the most complicated figure in all of English-language theater). Olivier has carved away much of that ambivalence: his Hamlet is fixed in meaning, and I don't find it to be the most satisfying meaning. He's started closing interpretive doors even before the film properly starts. After the dramatic, Gothic opening credits - stern serif font overlaid above crashing waves - Olivier recites an epigraph, taken from a cut speech in Act 1, Scene 4, which he then follows one sentence of his own words: "This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind." A standard reading of the play and the character, but hardly the only standard reading. Still, it starts pointing us in the direction Olivier wants to take the play: this is, first and above all, a psychoanalytical Hamlet. Its focus is on the tormented mind of the prince, drawing from the in-vogue readings of the play offered by Freud and later Freudians (meaning, among other things, that this Hamlet is much more interested in fucking his mom than Ophelia), cutting out as much as the political material as can be cut while leaving the narrative in place, and bending every aspect of the staging and cinematography to Hamlet's psychological upheaval.

Not the Hamlet I'd have directed, maybe, but I didn't direct it, and I would prefer a version of this (or any) play that has clear designs on what it wants us to take away to a version that simply lays the text out like a gutted fish and hopes for the best. Olivier's choices are bold, strong, and consistent, and his film moves with a visionary purpose not even approached by any subsequent screen Hamlet until Michael Almereyda's nutso 2000 film. Which should, again, remind us that just because a film is purposeful, that does not mean it is a good purpose. But in this case, I think it works. The psychoanalytic approach feels a little dated and corny, but it was pretty radical back in 1948, and it helps immensely to make the film go down easier that much of the thematic work is coming from the film's impressive, formidable production.

For what we have here is no less than an Expressionist film noir version of Hamlet, in which Olivier and his cinematographer Desmond Dickinson openly look to the experiments in deep focus and deep staging that had been going on in Hollywood over the previous decade, especially Welles and Gregg Toland's Citizen Kane. The film's presentation of Elsinore does not resemble a physically plausible castle in Denmark or anywhere else, so much as a pitch-black void that has been subdivided into rooms. It is first seen as a hulking matte painting seemingly made up only of turrets looming over crevasses; its interior is comprised almost entirely of yawning spaces that go back dozens of yards, allowing characters to be staged in isolated little pockets in group scenes. Through this space, the specially-built dolly rig carries the camera through like one more ghost haunting the halls, gliding across rooms with eerie, impossible smoothness that calls attention all the more to the powerfully large emptiness of the castle. Even in the handful of exterior scenes, such as the graveyard discovery of poor Yorick's skull, the set has been built and shot to emphasise the empty distance between foreground and background. Above and beyond this abyssal deep staging and flawless deep focus, Dickinson uses hard, strongly directional lighting to create high contrast even in scenes that are reasonably well-lit.

The film is thus terrific at creating a decaying atmosphere, a perfect place for death and life to co-exist uneasily, and indeed the film's take on the ghost scene is one of its highlights, an over-the-top riot of fog and half-seen human forms, with Olivier himself delivering the ghost's lines through a thick filter of aggressive sound editing. But the focus here is not phantasmagoria, but psychology: all of those great terrifying empty rooms and gaping headspace are expressions of Hamlet's unease, and maybe the general psychic rot of Elsinore. All of those impressive camera moves are dedicated to that end, including a tracking shot that goes within centimeters of the back of Olivier's skull, and then appears to literally enter his head through a dissolve, the better to pound home the idea of a psychologically-oriented Hamlet right before Olivier launches into the "To be or not to be" monologue, the most psychologically rich part of the play. He overplays his hand here, staging the speech on one of those doomy-looking turrets, plunging into the unseen chaos of the sea, but hell, at least you can't call it filmed theater.

That level of go-for-broke commitment to the expressive power of the images and their ability to add even more drama than what's already in the play means that this Hamlet routinely goes bonkers where a bit more restraint might have helped, but at least it has an impact. Howard Hawks famously said that a film was a success if it had three good scenes and no bad ones, and Hamlet beats this by one: the ghost, Yorick's grave, "The Murder of Gonzago" (pantomime structured smartly around reaction shots), and the climactic duel (a nimble exchange of well-acted asides and brilliant deep-focus shots of the poisoned wine) are all excellent scenes, and other than maybe Ophelia's mad scene, there are no scenes that actively don't work.

It is, to my mind, still the best filmed version of Hamlet, at least among those using the original text; it achieves this distinction without quite become top-tier filmed Shakespeare. For one thing, Olivier indulges himself too much with grave, glacial pacing; at 154 minutes, this is longer than it has any reason to be, even leaving the script alone. Far more significantly, there are some substantial problems with the cast. Olivier himself is magnificent: it's his best screen performance, tentatively searching his way through the psychological thickets of the scenario and reciting the dialogue as such a natural extension of his visible mood and the mood of the imagery that it completely skips over the usual traps of comprehension for modern types. The directing and acting are inseparable from each other, building scenes together; it's pure, unbridled egotism, but it works. But there's hardly any other good performances in the film; Felix Aylmer's Polonius is the obvious standout, capturing the doddering comedy of the addled old know-it-all with real sincerity and warmth behind the blathering. As for the rest, it's a race to the bottom: Eileen Herlie's Gertrude is probably the least-bad, and she's actually very good in her death scene, but Basil Sydney's Claudius is almost solely a prop upon which to project reaction shots. Jean Simmons' Ophelia is a disaster; she turns the mad scene into outright camp, and she plays the character's early reaction to Hamlet's bizarre behavior as a panicked buffoon rather than a maiden frightened for her safety and purity. Peter Cushing's Osric is even worse, a fey, mincing collection of the easiest tics for playing a courtier I can imagine.

Hamlet being Hamlet, having a strong central performance matters a great deal more than having lousy, forgettable performances on the sides, and the film still works; it even occasionally works brilliantly. Still, one wishes that Olivier might have devoted a bit more time to working with any of his actors as much as himself; this feels like it has the ingredients to be an all-timer of a Shakespeare film, but with so many hollow figures filling out the ensemble, it has to make do with being a perfectly good Shakespeare film. Which is still a real achievement, in 1948 as it is today, however limited.

Olivier's approach to preparing Hamlet for the screen started by mercilessly chopping material out: he removed the characters of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern entirely, and left no trace of Denmark's impending war. These changes, especially the former, have led to plenty of criticism in the years since the film premiered, but for myself, I'm all for it. The "full" version of Hamlet is (pace Kenneth Branagh) unreasonably long and was almost certainly not performed as such during Shakespeare's lifetime; considerable slicing must be done to make it a dramatically manageable object, and that slicing must be done judiciously and purposefully. I have my ups and downs with Olivier, but I'd never deny that the man knew Shakespeare, and had put a great deal of thought into what this particular play can be made to do to an audience. His choices all line up, moving the text towards a very distinct and coherent end; this is not just an edited Hamlet, it is a thoughtfully and carefully curated Hamlet.

It is, to be honest, not curated in the ways I would myself have preferred. Hamlet is a deeply ambivalent play and Hamlet himself an ambivalent character, the most complicated and at times vague figure in Shakespeare (which puts him in the running for the most complicated figure in all of English-language theater). Olivier has carved away much of that ambivalence: his Hamlet is fixed in meaning, and I don't find it to be the most satisfying meaning. He's started closing interpretive doors even before the film properly starts. After the dramatic, Gothic opening credits - stern serif font overlaid above crashing waves - Olivier recites an epigraph, taken from a cut speech in Act 1, Scene 4, which he then follows one sentence of his own words: "This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind." A standard reading of the play and the character, but hardly the only standard reading. Still, it starts pointing us in the direction Olivier wants to take the play: this is, first and above all, a psychoanalytical Hamlet. Its focus is on the tormented mind of the prince, drawing from the in-vogue readings of the play offered by Freud and later Freudians (meaning, among other things, that this Hamlet is much more interested in fucking his mom than Ophelia), cutting out as much as the political material as can be cut while leaving the narrative in place, and bending every aspect of the staging and cinematography to Hamlet's psychological upheaval.

Not the Hamlet I'd have directed, maybe, but I didn't direct it, and I would prefer a version of this (or any) play that has clear designs on what it wants us to take away to a version that simply lays the text out like a gutted fish and hopes for the best. Olivier's choices are bold, strong, and consistent, and his film moves with a visionary purpose not even approached by any subsequent screen Hamlet until Michael Almereyda's nutso 2000 film. Which should, again, remind us that just because a film is purposeful, that does not mean it is a good purpose. But in this case, I think it works. The psychoanalytic approach feels a little dated and corny, but it was pretty radical back in 1948, and it helps immensely to make the film go down easier that much of the thematic work is coming from the film's impressive, formidable production.

For what we have here is no less than an Expressionist film noir version of Hamlet, in which Olivier and his cinematographer Desmond Dickinson openly look to the experiments in deep focus and deep staging that had been going on in Hollywood over the previous decade, especially Welles and Gregg Toland's Citizen Kane. The film's presentation of Elsinore does not resemble a physically plausible castle in Denmark or anywhere else, so much as a pitch-black void that has been subdivided into rooms. It is first seen as a hulking matte painting seemingly made up only of turrets looming over crevasses; its interior is comprised almost entirely of yawning spaces that go back dozens of yards, allowing characters to be staged in isolated little pockets in group scenes. Through this space, the specially-built dolly rig carries the camera through like one more ghost haunting the halls, gliding across rooms with eerie, impossible smoothness that calls attention all the more to the powerfully large emptiness of the castle. Even in the handful of exterior scenes, such as the graveyard discovery of poor Yorick's skull, the set has been built and shot to emphasise the empty distance between foreground and background. Above and beyond this abyssal deep staging and flawless deep focus, Dickinson uses hard, strongly directional lighting to create high contrast even in scenes that are reasonably well-lit.

The film is thus terrific at creating a decaying atmosphere, a perfect place for death and life to co-exist uneasily, and indeed the film's take on the ghost scene is one of its highlights, an over-the-top riot of fog and half-seen human forms, with Olivier himself delivering the ghost's lines through a thick filter of aggressive sound editing. But the focus here is not phantasmagoria, but psychology: all of those great terrifying empty rooms and gaping headspace are expressions of Hamlet's unease, and maybe the general psychic rot of Elsinore. All of those impressive camera moves are dedicated to that end, including a tracking shot that goes within centimeters of the back of Olivier's skull, and then appears to literally enter his head through a dissolve, the better to pound home the idea of a psychologically-oriented Hamlet right before Olivier launches into the "To be or not to be" monologue, the most psychologically rich part of the play. He overplays his hand here, staging the speech on one of those doomy-looking turrets, plunging into the unseen chaos of the sea, but hell, at least you can't call it filmed theater.

That level of go-for-broke commitment to the expressive power of the images and their ability to add even more drama than what's already in the play means that this Hamlet routinely goes bonkers where a bit more restraint might have helped, but at least it has an impact. Howard Hawks famously said that a film was a success if it had three good scenes and no bad ones, and Hamlet beats this by one: the ghost, Yorick's grave, "The Murder of Gonzago" (pantomime structured smartly around reaction shots), and the climactic duel (a nimble exchange of well-acted asides and brilliant deep-focus shots of the poisoned wine) are all excellent scenes, and other than maybe Ophelia's mad scene, there are no scenes that actively don't work.

It is, to my mind, still the best filmed version of Hamlet, at least among those using the original text; it achieves this distinction without quite become top-tier filmed Shakespeare. For one thing, Olivier indulges himself too much with grave, glacial pacing; at 154 minutes, this is longer than it has any reason to be, even leaving the script alone. Far more significantly, there are some substantial problems with the cast. Olivier himself is magnificent: it's his best screen performance, tentatively searching his way through the psychological thickets of the scenario and reciting the dialogue as such a natural extension of his visible mood and the mood of the imagery that it completely skips over the usual traps of comprehension for modern types. The directing and acting are inseparable from each other, building scenes together; it's pure, unbridled egotism, but it works. But there's hardly any other good performances in the film; Felix Aylmer's Polonius is the obvious standout, capturing the doddering comedy of the addled old know-it-all with real sincerity and warmth behind the blathering. As for the rest, it's a race to the bottom: Eileen Herlie's Gertrude is probably the least-bad, and she's actually very good in her death scene, but Basil Sydney's Claudius is almost solely a prop upon which to project reaction shots. Jean Simmons' Ophelia is a disaster; she turns the mad scene into outright camp, and she plays the character's early reaction to Hamlet's bizarre behavior as a panicked buffoon rather than a maiden frightened for her safety and purity. Peter Cushing's Osric is even worse, a fey, mincing collection of the easiest tics for playing a courtier I can imagine.

Hamlet being Hamlet, having a strong central performance matters a great deal more than having lousy, forgettable performances on the sides, and the film still works; it even occasionally works brilliantly. Still, one wishes that Olivier might have devoted a bit more time to working with any of his actors as much as himself; this feels like it has the ingredients to be an all-timer of a Shakespeare film, but with so many hollow figures filling out the ensemble, it has to make do with being a perfectly good Shakespeare film. Which is still a real achievement, in 1948 as it is today, however limited.