Australian Winter of Blood: Ghost-colonialism

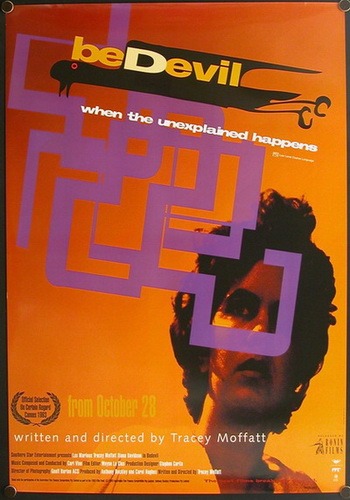

I will begin by saying that I have seen the film we are about to dig into with three different arrangements of capital letters: Bedevil, BeDevil, and beDevil. I have decided to favor the third, partly because it's how the title is rendered onscreen, partially because that's how a couple of art museums refer to it, and that seems to be especially trustworthy, and partially because I like the way it looks best.

Whatever the case, we're talking about the 1993 feature debut (and, to date, only feature) directed by Tracey Moffatt, by trade a photographer and creator of gallery installations, though she dabbled from time to time in movies, having by this point produced two well-regarded avant-garde shorts, Nice Coloured Girls in 1987 and Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy in 1990. With this film she also became the first woman of Aboriginal Australian heritage to direct a feature, which seems like it should be enough entirely on its own to have given the film a much more visible profile than it has enjoyed; and if it wasn't, I would like to imagine the fact that it's such a stunning feast of visual creativity and unexpected tonal shifts might have done the job. But no, sadly, the film has languished in fairly unmixed obscurity, nearly impossible to lay hands on in addition to be mostly unheralded.

This is an outrageous pity, because beDevil is, at a minimum, aggressively unusual and rare. It's definitely imperfect, for the most disappointingly predictable reason there is: this is an anthology film, and the third and final segment is a pretty substantial step down from the first two. It is not, in and of itself, bad - but having already been wowed that the second segment was somehow even better than the bravura opening, I was perhaps extra-vulnerable to being disappointed. It's also at least slightly irksome that Moffatt puts exactly no effort into pretending this is anything other than three standalone stories, without even the thinnest tendril of a framework; the mildest of nitpicks, to be sure.

All three stories are ghost stories, variations on the idea of a tragic past shoving its way into the present, and all three expressly cast this in terms of Australia's history of colonialism. Moffatt has, when pressed, asked that we not think of beDevil as a post-colonial text; the daughter of an Irish father and Aboriginal mother, raised from a young age by a white foster family, she drew from all the different cultural buckets available to her in conceiving the script around stories she heard growing up, and would prefer we think of the film as the product of all those different influences mixed together. And this is, of course, a request we had ought to respect. But my God, it's hard not to wonder if she actually means that; beDevil's three stories have such potent racial overtones that it seems genuinely impossible not to read them through that lens. For, as much as ghosts qua ghosts represent the past interfering with the present, they also make a fine metaphor for a sorry national history continuing to negatively impact Aboriginal lives deep into the 20th Century.

All of the above and more besides are very quickly laid out in the opening story, "Mister Chuck", which at least in the broad strokes takes the form of re-enactments nestled inside a talking head documentary. Rick (Jack Charles), an Aboriginal man, and Shelley (Diana Davidson), a white woman, both of them well along into middle age, share their stories about the same patch of land - for Shelley, it's a site of fond familial memories, while for Rick, the memories are much more about the shitty things that have happened there, and that idiot whites have done. The film isn't bashful about making sure we see the distinction: Rick's first long monologue ends on a scornful, dismissive reference to an island, which immediately cuts to Shelley saying "island" in tones of loving nostalgia. The visual contrast between them gets at the same distinction: Rick is shot against a bland painted cinderblock wall, behind a sheet of glass (it seems likely that he is in prison, though the film never suggests this outside of the institutional set), lit with flat neutral lighting, while Shelly is in a busy, overstuffed domestic space, with bright, cheery sunlight hammering in from the right.

The movie presents, in a fragmentary and somewhat nonlinear way, events in Rick's childhood, when he was seven years old (played by Kenneth Avery), and was attacked by something living in a muddy bog, and then four years later (played by Ben Kennedy), when a crude movie theater was built over the bog by whites, leading to another altercation between the boy and the malevolent presence, which may be related to the American soldier who drowned there during the war. So we're already looking not just at two time periods getting all tangled up, but three, with the two narrators presenting a clumsy and meandering recap of events from both past time frames that only gets at the impression of what happened, without doing much to pin it down. This includes Rick's elusive recollection of an even graver threat than any ghost, the unseen uncle who abused him and his sisters, only ever seen as a looming silhouette and only heard as a sharp, guttural, barking voice.

The piecemeal narration of the sequence pulls in two directions: it's about the way that time allows us to put a narrative framework around history, but it also presents that narrative in such a loose, shaggy way that it's hard to make out what's happening as more than a series of impressions. And good God, such impressions they are! Following on the aesthetic she developed in Night Cries, Moffatt sets "Mister Chuck" - and most of beDevil, for that matter - on sets that are flagrantly artificial, with solid color painted skies only a few feet from the actors, and ground that isn't even slightly pretending to be real earth. This creates both an abstract theatrical feeling, while also plunging us right into the uncanny: it both does and doesn't feel like a real location, or even a memory of a location. It feels like the minimum necessary to fulfill the requirements of the plot, though at times oddly detailed given how abstract it is. The lateral tracking shot along the swamp that opens the film (after the colorful opening credits, presenting something like a ritual dance), for example, is full of grass and dead trees and thick water ebbing and flowing, and feels quite fleshed-out, given how clearly the lighting and background are wrenching us out of anything even mildly close to realism.

It ends up being a location especially well-suited to horror - and horror this certainly is, not even in some abstract, artful way. When the segment ends with Rick neutrally describing his last run-in with the ghost, as we watch his younger self with a perfectly flat expression, I had a delightful shiver of nerves. But it is horror generated through a very peculiar, unexpected method, one that combines playful artifice with the just plain weird; it recalls some of the more theatrically florid Japanese horror films of the '60s and '70s - there is even a little bit of the legendary cult film House here.

The next segment, "Choo Choo Choo Choo", takes this same style, and the same theatrical uncanniness, and pushes it even farther (truth be told, it was only here that I found myself thinking of House, mostly during a visual effect in the last scene that faultlessly splits the difference between ridiculously cheesy and silly, and genuinely bone-chilling in how otherworldly the ghost looks in the shot). And here, there's a much starker split with the artificial abstraction of the past, and the grungy realism of the present. Ruby (Auriel Andrews), in the present, once again talks directly to the camera, but if the last two narrators were more like interview subjects, Ruby is our garrulous host, welcoming us to her rundown rural encampment, where many years ago, she (played by Moffatt) and her family were tormented by a haunted railway track. This segment once again presents a gap between the stories we tell about our past and the past itself: while the material in the past is full of dire, moody atmospherics, and Carl Vine's score leans hardest into spooky haunted house cues (the music is, in general, a weakness, reliant on cliché and cheap early-'90s elecrtronic instruments), the material in the present is borderline comic. And at certain points, such as the meandering, pointless recollections of Old Mickey (Les Foxcroft), or Ruby's impromptu cooking show segment that ends in a fight with the ancient-looking Maudie (Mawuyul Yanthalwuy) over the proper way to sauce a dish, that border evaporates.

The conflict between the openly goofy and the self-consciously creepy yields enormous dividends throughout this sequence, the highlight of beDevil. In the form of the older Ruby, it has a wonderfully blut perspective on dealing with terrible things in the past and approaching problems with good-humored pragmatism; through the nervous, uncertain expressions worn by Moffat as the younger Ruby, it is also throughly effective as an effectively rattled ghost story. It's smart, visually imaginative, and fun - a remarkable blend of well-controlled tones and punchy artificial imagery.

Unfortunately, it doesn't take long for it to be clear that the last segment, "Lovin' the Spin I'm In", is going to be operating at a lower level of ingenious delirium than the last two stories. A white property owner, Dimitri (Lex Marinos) is trying to get overseas investors (John Conamos, Kee Chan) to fund the casino he wants to build on the site of a mostly abandoned warehouse. Unfortunately, the sole squatter, a Torres Strait islander named Emelda (Debai Baira) refuses to leave as long as the ghosts of her son Beba (Pinau Ghee) and his lover Minnie (Patricia Handy) remain in the place. Meanwhile, a teenager from across the street, Spiro (Riccardo Natoli) watches the whole situation with amazement, as his mother (Dina Panozzo) tells him of the tragic history of the lovers.

There's nothing as-such wrong with any of this: Moffat's love of artificial exteriors remains firmly in place, and there's something sweetly classical about the idea of a steadfast love beyond the grave that grows increasingly weird and freaky as the sequence progresses. But this never seems to have a handle on its ideas the way the other two segments do, and the increased quantity of plot gets in the way of the atmosphere a bit. Still, anthology films should just be expected to drop the ball somewhere, and this was playing an extraordinary game prior to this. Besides, even a more sedate and unfocused version of beDevil is still pretty striking, given how wild it is at its heights. This is, all in all, an excellent mixture of tightly-controlled genre filmmaking and bold avant-garde style, deeply saturated with a feeling of personal history operating through complex social currents. It's kind of got a little something for everyone, and it's nothing short of a crime that that film has such a low profile, and is so hard to access.

Body Count: These are "be spooky and not harmful" ghosts, not killer ghosts. But if we count the ghosts themselves, we could say 4.

Whatever the case, we're talking about the 1993 feature debut (and, to date, only feature) directed by Tracey Moffatt, by trade a photographer and creator of gallery installations, though she dabbled from time to time in movies, having by this point produced two well-regarded avant-garde shorts, Nice Coloured Girls in 1987 and Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy in 1990. With this film she also became the first woman of Aboriginal Australian heritage to direct a feature, which seems like it should be enough entirely on its own to have given the film a much more visible profile than it has enjoyed; and if it wasn't, I would like to imagine the fact that it's such a stunning feast of visual creativity and unexpected tonal shifts might have done the job. But no, sadly, the film has languished in fairly unmixed obscurity, nearly impossible to lay hands on in addition to be mostly unheralded.

This is an outrageous pity, because beDevil is, at a minimum, aggressively unusual and rare. It's definitely imperfect, for the most disappointingly predictable reason there is: this is an anthology film, and the third and final segment is a pretty substantial step down from the first two. It is not, in and of itself, bad - but having already been wowed that the second segment was somehow even better than the bravura opening, I was perhaps extra-vulnerable to being disappointed. It's also at least slightly irksome that Moffatt puts exactly no effort into pretending this is anything other than three standalone stories, without even the thinnest tendril of a framework; the mildest of nitpicks, to be sure.

All three stories are ghost stories, variations on the idea of a tragic past shoving its way into the present, and all three expressly cast this in terms of Australia's history of colonialism. Moffatt has, when pressed, asked that we not think of beDevil as a post-colonial text; the daughter of an Irish father and Aboriginal mother, raised from a young age by a white foster family, she drew from all the different cultural buckets available to her in conceiving the script around stories she heard growing up, and would prefer we think of the film as the product of all those different influences mixed together. And this is, of course, a request we had ought to respect. But my God, it's hard not to wonder if she actually means that; beDevil's three stories have such potent racial overtones that it seems genuinely impossible not to read them through that lens. For, as much as ghosts qua ghosts represent the past interfering with the present, they also make a fine metaphor for a sorry national history continuing to negatively impact Aboriginal lives deep into the 20th Century.

All of the above and more besides are very quickly laid out in the opening story, "Mister Chuck", which at least in the broad strokes takes the form of re-enactments nestled inside a talking head documentary. Rick (Jack Charles), an Aboriginal man, and Shelley (Diana Davidson), a white woman, both of them well along into middle age, share their stories about the same patch of land - for Shelley, it's a site of fond familial memories, while for Rick, the memories are much more about the shitty things that have happened there, and that idiot whites have done. The film isn't bashful about making sure we see the distinction: Rick's first long monologue ends on a scornful, dismissive reference to an island, which immediately cuts to Shelley saying "island" in tones of loving nostalgia. The visual contrast between them gets at the same distinction: Rick is shot against a bland painted cinderblock wall, behind a sheet of glass (it seems likely that he is in prison, though the film never suggests this outside of the institutional set), lit with flat neutral lighting, while Shelly is in a busy, overstuffed domestic space, with bright, cheery sunlight hammering in from the right.

The movie presents, in a fragmentary and somewhat nonlinear way, events in Rick's childhood, when he was seven years old (played by Kenneth Avery), and was attacked by something living in a muddy bog, and then four years later (played by Ben Kennedy), when a crude movie theater was built over the bog by whites, leading to another altercation between the boy and the malevolent presence, which may be related to the American soldier who drowned there during the war. So we're already looking not just at two time periods getting all tangled up, but three, with the two narrators presenting a clumsy and meandering recap of events from both past time frames that only gets at the impression of what happened, without doing much to pin it down. This includes Rick's elusive recollection of an even graver threat than any ghost, the unseen uncle who abused him and his sisters, only ever seen as a looming silhouette and only heard as a sharp, guttural, barking voice.

The piecemeal narration of the sequence pulls in two directions: it's about the way that time allows us to put a narrative framework around history, but it also presents that narrative in such a loose, shaggy way that it's hard to make out what's happening as more than a series of impressions. And good God, such impressions they are! Following on the aesthetic she developed in Night Cries, Moffatt sets "Mister Chuck" - and most of beDevil, for that matter - on sets that are flagrantly artificial, with solid color painted skies only a few feet from the actors, and ground that isn't even slightly pretending to be real earth. This creates both an abstract theatrical feeling, while also plunging us right into the uncanny: it both does and doesn't feel like a real location, or even a memory of a location. It feels like the minimum necessary to fulfill the requirements of the plot, though at times oddly detailed given how abstract it is. The lateral tracking shot along the swamp that opens the film (after the colorful opening credits, presenting something like a ritual dance), for example, is full of grass and dead trees and thick water ebbing and flowing, and feels quite fleshed-out, given how clearly the lighting and background are wrenching us out of anything even mildly close to realism.

It ends up being a location especially well-suited to horror - and horror this certainly is, not even in some abstract, artful way. When the segment ends with Rick neutrally describing his last run-in with the ghost, as we watch his younger self with a perfectly flat expression, I had a delightful shiver of nerves. But it is horror generated through a very peculiar, unexpected method, one that combines playful artifice with the just plain weird; it recalls some of the more theatrically florid Japanese horror films of the '60s and '70s - there is even a little bit of the legendary cult film House here.

The next segment, "Choo Choo Choo Choo", takes this same style, and the same theatrical uncanniness, and pushes it even farther (truth be told, it was only here that I found myself thinking of House, mostly during a visual effect in the last scene that faultlessly splits the difference between ridiculously cheesy and silly, and genuinely bone-chilling in how otherworldly the ghost looks in the shot). And here, there's a much starker split with the artificial abstraction of the past, and the grungy realism of the present. Ruby (Auriel Andrews), in the present, once again talks directly to the camera, but if the last two narrators were more like interview subjects, Ruby is our garrulous host, welcoming us to her rundown rural encampment, where many years ago, she (played by Moffatt) and her family were tormented by a haunted railway track. This segment once again presents a gap between the stories we tell about our past and the past itself: while the material in the past is full of dire, moody atmospherics, and Carl Vine's score leans hardest into spooky haunted house cues (the music is, in general, a weakness, reliant on cliché and cheap early-'90s elecrtronic instruments), the material in the present is borderline comic. And at certain points, such as the meandering, pointless recollections of Old Mickey (Les Foxcroft), or Ruby's impromptu cooking show segment that ends in a fight with the ancient-looking Maudie (Mawuyul Yanthalwuy) over the proper way to sauce a dish, that border evaporates.

The conflict between the openly goofy and the self-consciously creepy yields enormous dividends throughout this sequence, the highlight of beDevil. In the form of the older Ruby, it has a wonderfully blut perspective on dealing with terrible things in the past and approaching problems with good-humored pragmatism; through the nervous, uncertain expressions worn by Moffat as the younger Ruby, it is also throughly effective as an effectively rattled ghost story. It's smart, visually imaginative, and fun - a remarkable blend of well-controlled tones and punchy artificial imagery.

Unfortunately, it doesn't take long for it to be clear that the last segment, "Lovin' the Spin I'm In", is going to be operating at a lower level of ingenious delirium than the last two stories. A white property owner, Dimitri (Lex Marinos) is trying to get overseas investors (John Conamos, Kee Chan) to fund the casino he wants to build on the site of a mostly abandoned warehouse. Unfortunately, the sole squatter, a Torres Strait islander named Emelda (Debai Baira) refuses to leave as long as the ghosts of her son Beba (Pinau Ghee) and his lover Minnie (Patricia Handy) remain in the place. Meanwhile, a teenager from across the street, Spiro (Riccardo Natoli) watches the whole situation with amazement, as his mother (Dina Panozzo) tells him of the tragic history of the lovers.

There's nothing as-such wrong with any of this: Moffat's love of artificial exteriors remains firmly in place, and there's something sweetly classical about the idea of a steadfast love beyond the grave that grows increasingly weird and freaky as the sequence progresses. But this never seems to have a handle on its ideas the way the other two segments do, and the increased quantity of plot gets in the way of the atmosphere a bit. Still, anthology films should just be expected to drop the ball somewhere, and this was playing an extraordinary game prior to this. Besides, even a more sedate and unfocused version of beDevil is still pretty striking, given how wild it is at its heights. This is, all in all, an excellent mixture of tightly-controlled genre filmmaking and bold avant-garde style, deeply saturated with a feeling of personal history operating through complex social currents. It's kind of got a little something for everyone, and it's nothing short of a crime that that film has such a low profile, and is so hard to access.

Body Count: These are "be spooky and not harmful" ghosts, not killer ghosts. But if we count the ghosts themselves, we could say 4.

Categories: anthology films, avant-garde, horror, oz/kiwi cinema, scary ghosties, summer of blood