Fell in love with a girl

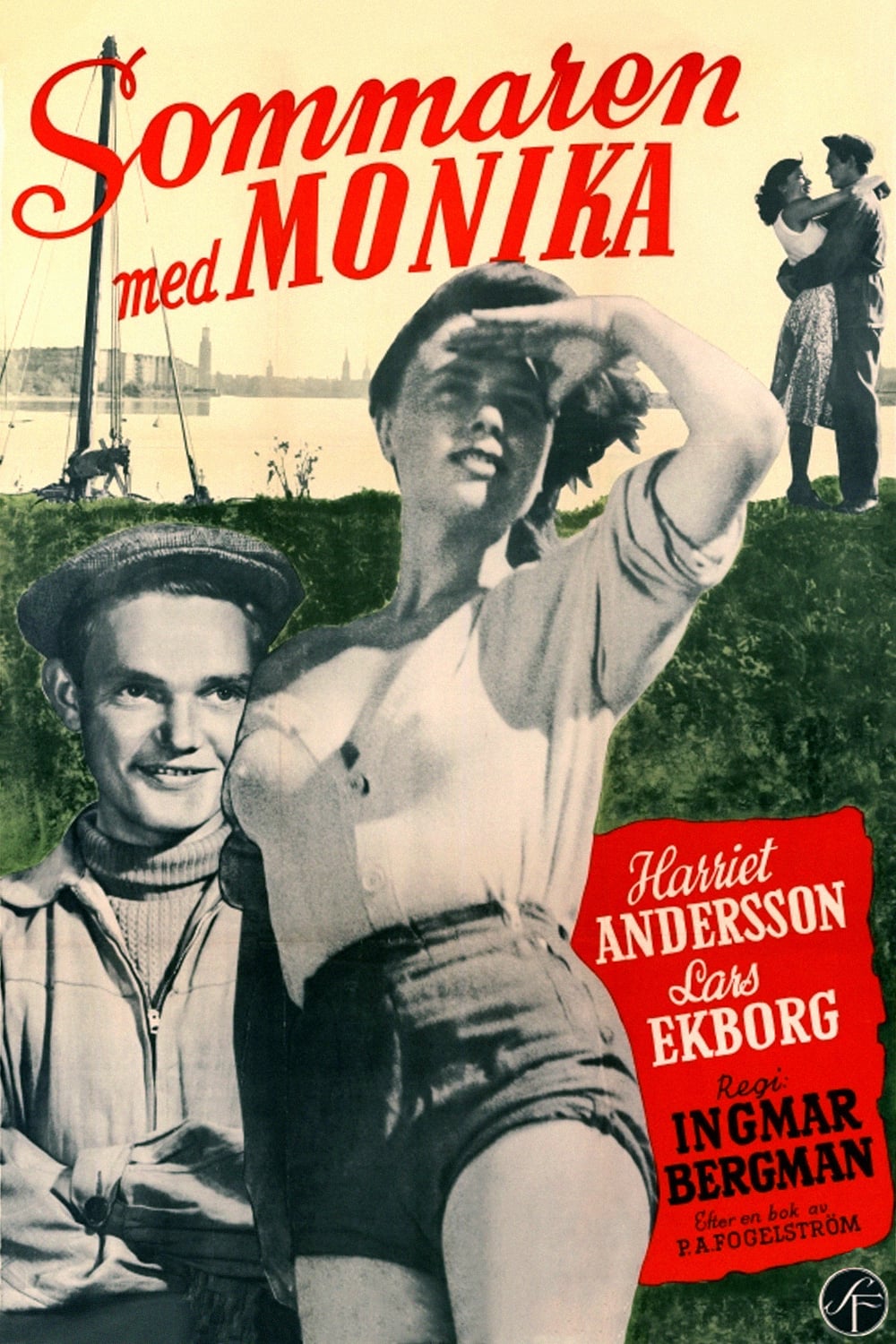

1953's Summer with Monika, Ingmar Bergman's twelfth feature film as director, was also the film with which he first found major international success, though that success had very little to do with critical recognition of his talent. Rather, it's because Summer with Monika had what was, at the time, a groundbreaking depiction of nudity, and while this was not seen as an especially big deal in its native Sweden (it followed, by two years, Arne Mattsson's One Summer of Happiness, which showed more), it caused quite a stir elsewhere. Perhaps most infamously, in the United States, it was released in 1955 by Kroger Babb, an exploitation film producer and distributor, who carved the film down to 62 minutes, re-dubbed, and gave it the appropriately sweaty title Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl. The film (along with One Summer of Happiness) was substantially responsible for creating Sweden's international reputation as a nation of liberated sexual progressives who were all blonde and pert.

Which is ironic, on top of everything else, because Summer with Monika in its undiluted 96-minute version is specifically about the destructive tendencies of unbridled sexual libertinism. But that comes nearer the end, after a much longer stretch of movie that is, indeed, all about the heady emotional richness of youthful sexual ardor, and this is substantially the more compelling material - as written, as acted, as shot. So it does end up feeling like the film is "about" eroticism, though whether this naturally means it is an "erotic film" is something we can debate (the fact that Babb had to slice it to ribbons to sell it on the exploitation circuit suggests that it's maybe not).

The film feels like a natural development from both Summer Interlude and the first segment of Waiting Women, though unlike those, it is not an original story; the film was adapted from a novel by Per Anders Fogelström, who worked with Bergman on the script. Even so, it's closely of a piece with them, telling a story of young lovers in a summer idyll on the Stockholm archipelago, where the peculiar qualities of the summer light does the great majority of the work in setting tone and emotion, and the summer itself feels like a character on par with the human protagonists. It even functions as a sort of sequel to Waiting Women, which ends with the adults electing to do nothing while a pair of young lovers head off to spend the summer having fun and making mistakes. Summer with Monika starts just a little bit earlier than that, with Monika (Harriet Andersson) and Harry (Lars Ekborg) meeting for the first time, a couple of working class kids with dead-end jobs and dead-end lives in Stockholm. Impulsively, they decide to run away from their families and frolic around the archipelago for the few precious weeks of the summer. And by "frolic" I mean "screw".

It is considerably more sour than either of those films. Summer Interlude is a tragedy, but a romantic one; it kills off one of its lovers to preserve for the other one the ability to look back on the summer as a time of unmixed bliss. Waiting Women, for its part, was the first Bergman film with a generally optimistic ending, grown up wisdom smilingly warmly on the impetuousness of youth. Summer with Monika saves time at the end to bring the couple back to Stockholm and the grubby reality of life there; one might with cause even call it cynical in its depiction of a youthful summer love curdling and turning to ruin back in the real world (Swedish critics at the time certainly found it thus; it was greeted with uncharacteristically cool reviews for a Bergman film, mostly centered on how he amplified Monika's most unappealing characteristics). But it is a hard-won pessimism, all the sharper for how well the film luxuriates in the sensuality of the summer and the young lovers' physicality.

The bulk of the film's effect comes from two sources. The one that isn't very surprising, but not any less effective for it, is Gunnar Fischer's cinematography; by this point, he and Bergman and the archipelago all knew each other very well, and as the extension and development of the work he'd done in shooting Summer Interlude over two years prior, Summer with Monika is both a triumph in its own right and a fine challenge the hazy dream state of the earlier film. Part of this is purely a matter of physics: Summer Interlude was shot between early April and mid June, while Summer with Monika was shot between late July and early October. Presuming that in both cases, the island scenes were shot in the most "summery" parts of those respective schedules, that still means that Monika was shot when the light was much further along its path back to winter darkness, and this manifests in far less expansive a field of greys than in the earlier film. The light in Summer Interlude glows, diffuse and warm; the light in Monika gleams, hard and bright. There are more silhouettes, and more hard edge lighting. There's a blunt solidity to these images, which shake lose the haze of memory found in both Summer Interlude and the summer scenes of Waiting Women, replacing it with direct physical presence. And this fits not just the caustic third act, but also this film's insistent focus on carnality and fleshiness; we are hyper-aware of Monika and Harry's bodies, as physical objects interacting with the sea and sun every bit as much as hormonal bags of young lust. The tangibility of their skin as Fischer shoots it is a huge part of why this works, especially in contrast with the much smearier look of the scenes back in Stockholm. It is probably a less beautiful film than Summer Interlude, but not really by all that much, and I'd still be inclined to say this is Fischer's best work with Bergman to this point.

The other foundation of Monika's success comes from Monika herself: Harriet Andersson's performance is a marvel, decidedly the best work by any actor in a Bergman film thus far. She would go on to be one of the cornerstones of the stock company who appear over and over again in his most renowned masterpieces; while she is the second member of that stock company to show up, Gunnar Björnstrand hadn't received a showcase role yet. Monika is a showcase and then some. Bergman and Andersson were already having an affair by the time the film went into production, and there's no mistaking how the director hands scene after scene, shot after shot, to his younger lover, but her screen presence is such that I think she surely would have demanded that consideration anyway. The trace that their affair does leave is in the film's besotted fascination with Andersson's body; I think one has to wait 66 whole years until Portrait of a Lady on Fire to find a film that benefits so much from the intimate knowledge of how their lover's body moves and what it most exciting and stimulating, sexually and aesthetically, about her.

But this is all orthogonal to Andersson's performance; she certainly takes advantage of the way the camera loves her, and the freedom to simply exist in her body (Andersson has said in later interviews that she never had a doubt about appearing naked on screen, and never felt a hint of discomfort during the shoot; it's easy to tell), but the performance goes beyond mere sexuality. It necessarily includes sexuality, for this is a deeply sexual film. But it's also a film about being, at least temporarily, free of constriction and rules, able to simply enjoy moments of bliss and the feel of the water and the son, and Andersson hungrily embraces that bliss; when she's forced back to Stockholm, the harshness that sweeps into her performance never feels arbitrary or forced, but a natural result of having that bliss forcibly taken away. The third act is, undoubtedly, where most of the film's problems reside, and the way that Monika becomes raging and unlikable is certainly one of them; it might have worked in the book, which by all accounts is oriented more around Harry (as implied by the title), but the film has brought us into Monika's emotional state so fully that being dropped out of it to watch her thrash about in a kind of nihilistic hedonism is something we're simply not prepared for. But this is never Andersson's fault; she maintains steady control of the character, and the visuals continue to hang on her smallest gestures, culminating in an astonishing medium close-up where she looks directly into the camera, a moment that made this film the toast of the young French critics who'd later go on to found the New Wave.

The dark flipside to Andersson's performance is that Summer with Monika is a two-hander. And while even the casual Bergman-heads undoubtedly perked up happily when Andersson's name first cropped up, Lars Ekborg appeared in a grand total of one Bergman film after this, a small role in a subplot of 1958's The Magician. If you knew going into the film that one of the leads would become one of the director's most crucial collaborators, and the other was going to get a throwaway role years down the line, I am sure you'd have no problem guessing which was which. Andersson wipes the floor with Ekborg, who simply doesn't have the presence to hold his own while his co-star and her director-lover are both pulling focus away. While she captures the horny joy of being young, stupid, and carefree, and the self-negating terror of losing those things, he just rolls with whatever the film gives him; he's so detached from the urgent passionate eroticism underpinning the story that he can't even convincingly seem turned-on when he's staring directly at Andersson's naked chest.

This is more of an inconvenience than an actual problem when the film has the summer atmosphere and Andersson's dynamo performance to draw from. Once the action switches back to Stockholm and what follows that summer, however, it also recenters Harry and realigns itself to him, and this is where Ekborg's shallow performance starts causing real damage. The shift in Monika's personality is already asking a lot; having no concrete, strong personality to tie ourselves to makes it very hard to find a path through thus final scenes. And this is maybe something that accentuates the curdled feeling that the original critics rejected; it definitely makes it harder to care. There is something that kind of works here, though: the film is all about how summer turns into something cold and grey and upsetting, and by dropping us on our heads as we get locked out of Monika, the film basically embodies that theme in its own structure. I don't imagine that was intentional, and it doesn't make the final third any more satisfying of an experience, but it's sort of neat.

Which is ironic, on top of everything else, because Summer with Monika in its undiluted 96-minute version is specifically about the destructive tendencies of unbridled sexual libertinism. But that comes nearer the end, after a much longer stretch of movie that is, indeed, all about the heady emotional richness of youthful sexual ardor, and this is substantially the more compelling material - as written, as acted, as shot. So it does end up feeling like the film is "about" eroticism, though whether this naturally means it is an "erotic film" is something we can debate (the fact that Babb had to slice it to ribbons to sell it on the exploitation circuit suggests that it's maybe not).

The film feels like a natural development from both Summer Interlude and the first segment of Waiting Women, though unlike those, it is not an original story; the film was adapted from a novel by Per Anders Fogelström, who worked with Bergman on the script. Even so, it's closely of a piece with them, telling a story of young lovers in a summer idyll on the Stockholm archipelago, where the peculiar qualities of the summer light does the great majority of the work in setting tone and emotion, and the summer itself feels like a character on par with the human protagonists. It even functions as a sort of sequel to Waiting Women, which ends with the adults electing to do nothing while a pair of young lovers head off to spend the summer having fun and making mistakes. Summer with Monika starts just a little bit earlier than that, with Monika (Harriet Andersson) and Harry (Lars Ekborg) meeting for the first time, a couple of working class kids with dead-end jobs and dead-end lives in Stockholm. Impulsively, they decide to run away from their families and frolic around the archipelago for the few precious weeks of the summer. And by "frolic" I mean "screw".

It is considerably more sour than either of those films. Summer Interlude is a tragedy, but a romantic one; it kills off one of its lovers to preserve for the other one the ability to look back on the summer as a time of unmixed bliss. Waiting Women, for its part, was the first Bergman film with a generally optimistic ending, grown up wisdom smilingly warmly on the impetuousness of youth. Summer with Monika saves time at the end to bring the couple back to Stockholm and the grubby reality of life there; one might with cause even call it cynical in its depiction of a youthful summer love curdling and turning to ruin back in the real world (Swedish critics at the time certainly found it thus; it was greeted with uncharacteristically cool reviews for a Bergman film, mostly centered on how he amplified Monika's most unappealing characteristics). But it is a hard-won pessimism, all the sharper for how well the film luxuriates in the sensuality of the summer and the young lovers' physicality.

The bulk of the film's effect comes from two sources. The one that isn't very surprising, but not any less effective for it, is Gunnar Fischer's cinematography; by this point, he and Bergman and the archipelago all knew each other very well, and as the extension and development of the work he'd done in shooting Summer Interlude over two years prior, Summer with Monika is both a triumph in its own right and a fine challenge the hazy dream state of the earlier film. Part of this is purely a matter of physics: Summer Interlude was shot between early April and mid June, while Summer with Monika was shot between late July and early October. Presuming that in both cases, the island scenes were shot in the most "summery" parts of those respective schedules, that still means that Monika was shot when the light was much further along its path back to winter darkness, and this manifests in far less expansive a field of greys than in the earlier film. The light in Summer Interlude glows, diffuse and warm; the light in Monika gleams, hard and bright. There are more silhouettes, and more hard edge lighting. There's a blunt solidity to these images, which shake lose the haze of memory found in both Summer Interlude and the summer scenes of Waiting Women, replacing it with direct physical presence. And this fits not just the caustic third act, but also this film's insistent focus on carnality and fleshiness; we are hyper-aware of Monika and Harry's bodies, as physical objects interacting with the sea and sun every bit as much as hormonal bags of young lust. The tangibility of their skin as Fischer shoots it is a huge part of why this works, especially in contrast with the much smearier look of the scenes back in Stockholm. It is probably a less beautiful film than Summer Interlude, but not really by all that much, and I'd still be inclined to say this is Fischer's best work with Bergman to this point.

The other foundation of Monika's success comes from Monika herself: Harriet Andersson's performance is a marvel, decidedly the best work by any actor in a Bergman film thus far. She would go on to be one of the cornerstones of the stock company who appear over and over again in his most renowned masterpieces; while she is the second member of that stock company to show up, Gunnar Björnstrand hadn't received a showcase role yet. Monika is a showcase and then some. Bergman and Andersson were already having an affair by the time the film went into production, and there's no mistaking how the director hands scene after scene, shot after shot, to his younger lover, but her screen presence is such that I think she surely would have demanded that consideration anyway. The trace that their affair does leave is in the film's besotted fascination with Andersson's body; I think one has to wait 66 whole years until Portrait of a Lady on Fire to find a film that benefits so much from the intimate knowledge of how their lover's body moves and what it most exciting and stimulating, sexually and aesthetically, about her.

But this is all orthogonal to Andersson's performance; she certainly takes advantage of the way the camera loves her, and the freedom to simply exist in her body (Andersson has said in later interviews that she never had a doubt about appearing naked on screen, and never felt a hint of discomfort during the shoot; it's easy to tell), but the performance goes beyond mere sexuality. It necessarily includes sexuality, for this is a deeply sexual film. But it's also a film about being, at least temporarily, free of constriction and rules, able to simply enjoy moments of bliss and the feel of the water and the son, and Andersson hungrily embraces that bliss; when she's forced back to Stockholm, the harshness that sweeps into her performance never feels arbitrary or forced, but a natural result of having that bliss forcibly taken away. The third act is, undoubtedly, where most of the film's problems reside, and the way that Monika becomes raging and unlikable is certainly one of them; it might have worked in the book, which by all accounts is oriented more around Harry (as implied by the title), but the film has brought us into Monika's emotional state so fully that being dropped out of it to watch her thrash about in a kind of nihilistic hedonism is something we're simply not prepared for. But this is never Andersson's fault; she maintains steady control of the character, and the visuals continue to hang on her smallest gestures, culminating in an astonishing medium close-up where she looks directly into the camera, a moment that made this film the toast of the young French critics who'd later go on to found the New Wave.

The dark flipside to Andersson's performance is that Summer with Monika is a two-hander. And while even the casual Bergman-heads undoubtedly perked up happily when Andersson's name first cropped up, Lars Ekborg appeared in a grand total of one Bergman film after this, a small role in a subplot of 1958's The Magician. If you knew going into the film that one of the leads would become one of the director's most crucial collaborators, and the other was going to get a throwaway role years down the line, I am sure you'd have no problem guessing which was which. Andersson wipes the floor with Ekborg, who simply doesn't have the presence to hold his own while his co-star and her director-lover are both pulling focus away. While she captures the horny joy of being young, stupid, and carefree, and the self-negating terror of losing those things, he just rolls with whatever the film gives him; he's so detached from the urgent passionate eroticism underpinning the story that he can't even convincingly seem turned-on when he's staring directly at Andersson's naked chest.

This is more of an inconvenience than an actual problem when the film has the summer atmosphere and Andersson's dynamo performance to draw from. Once the action switches back to Stockholm and what follows that summer, however, it also recenters Harry and realigns itself to him, and this is where Ekborg's shallow performance starts causing real damage. The shift in Monika's personality is already asking a lot; having no concrete, strong personality to tie ourselves to makes it very hard to find a path through thus final scenes. And this is maybe something that accentuates the curdled feeling that the original critics rejected; it definitely makes it harder to care. There is something that kind of works here, though: the film is all about how summer turns into something cold and grey and upsetting, and by dropping us on our heads as we get locked out of Monika, the film basically embodies that theme in its own structure. I don't imagine that was intentional, and it doesn't make the final third any more satisfying of an experience, but it's sort of neat.