Australian Winter of Blood: In the bathroom, with the pipe

The Ozploitation cycle of the '70s and '80s was one of several exploitation film booms during that period, and like most of them, it was focused on genre films that could be made quickly and cheaply. This is, indeed, baked into the idea of "exploitation cinema", which is all about identifying profitable trends and hungry market sectors, and making films that satiate that hunger as fast as possible, before the trend has used itself up. However, unlike the contemporaneous exploitation films of Italy, say, or the Philippines, to name just two, Ozploitation occurred at precisely the same time as Australia's local version of the cinematic new waves that were happening all across the world in the '60s and '70s. The only other country where I know this to have happened was the United States, where the rise of the grind house and the New Hollywood Cinema occurred simultaneously; but the mature film industry of the U.S. already had ample room for independent and regional film production, and so the chronological proximity feels more like a random chance that left little reason for the two movements to speak to each other. Ozploitation and the Australian New Wave both grew out of the same inciting moment in the early '70s, and also had to share space in a film industry that essentially didn't exist prior to their start, and so they seem much more necessarily independent, two faces of the same coin.

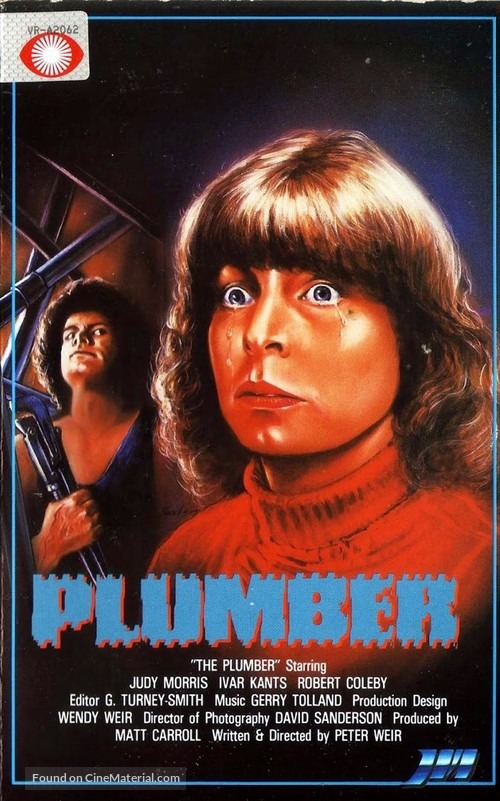

This brings us, in turn, to the early work of Peter Weir, who would leave his home country in the 1980s to become the first veteran of the resurgent Australian film industry to make it as a major Hollywood director. That history begins mostly likely with 1981's Gallipoli, a handsomely-done historical epic made with middlebrow respectability, but in the preceding decade, Weir's career was much stranger: he made film after film straddling the line between Ozploitation and the new wave so cleanly that they raise the question of whether the line existed at all. 1974's The Cars That Ate Paris is exactly the film that it sounds like, but so aware of and in love with its own absurdity as to feel more intellectual than "the town kills people using evil cars" possibly could. Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave, from 1975 and 1977, have the plot hooks of by-the-books thrillers, and the pensive mood and dreamlike abstraction of the most visionary art film. And that brings us to 1979's television film The Plumber, the last thing Weir made prior to Gallipoli, and probably the closest of any of them to being a completely straightforward horror-thriller, though one made with exceptional control over tone and pacing, and with an explicit interest in thinking through the challenges associated with social change.

Like many of Weir's films, The Plumber is about people in a closed system, and the interpersonal conflicts that arise as a result. That is, indeed, the entire conflict of the movie: the unendurable stress of being in trapped in a flat with somebody who you would particularly not want to be trapped with. The flat belongs to the Cowpers, Jill (Judy Morris) and Brian (Robert Coleby); Brian is a professor at a school in Adelaide, and Jill was working on her degree before they moved to this city and she put that on hold to focus on homemaking. It's not clear how much of that was a mutual decision and how much was Brian leaning on her, but as the movie progresses, it becomes pretty clear that he's not very interested in her needs when they come into conflict with his. But that's not the big problem here. The big problem is that one morning, a man named Max (Ivar Kants) shows up, claiming to be a plumber sent by the university to do routine check-ups on the bathrooms in this block. She's not terribly thrilled by this, especially without having been made aware of this beforehand, but she lets him in anyway. If she was in our position, and could hear Gerry Tolland's score leaping up into a tense, bass-driven drone the minute that Max shows up, she would surely think better of that decision, but all that means is that we get to jump right into the film's thriller mechanics.

And such mechanics they are! The story is as simple as simple gets: Max comes in, flimflams Jill, and then proceeds to act in a tremendously creepy way while apparently destroying her bathroom rather than doing anything to fix it. When she mentions this to Brian, he brushes right by it, far more concerned with a possible World Health Organization grant that will give him a career-changing trip to Geneva; he even goes so far as to suggest that she's more stressed out about the possibility of that movie than by what she claims is stressing her out. The next day, the whole process repeats, and then again next day. Every time through, the tension spikes up, and the feeling of Jill's helpless terror intensifies, with Morris looking more worn out and frantic by the minute. This all plays out over just 77 minutes, a running time that focuses and intensifies the film's narrative considerably, making Max's repeated incursions into Jill's home all the more horrifying by making it feel like they're piling up on each other with break. He's always coming or going, it feels like, and by rushing through the story events so quickly, Weir (who wrote the script in addition to directing) exaggerates how Jill loses control of her own home, making it less like she's being bothered by Max, and more like she's under siege.

To accentuate this feeling of constant acceleration in the storytelling, Weir and cinematographer David Sanderson use the simplest tool in the box, but also one of the most effecive: shot scale. The Plumber was made for television, which means a television budget, which is probably one reason it has such a small number of location (the living room and the increasingly unusable bathroom in the Cowper's flat, plus a lecture hall, and a few scattered exteriors), and that has already had the good effect of limiting the film's ability to meander. Hence that intense 77-minute plunge into paranoia. But it also means that it was going to be shown on a physical television set (though it was given theatrical distribution outside of Australia). And that means that Weir and Sanderson had to move in close to their characters. Much of the film consists of dueling exchanges of close-ups, giving us ample room to take in Kants's nasty smirk and Morris's miserable, helpless reactions; it neatly creates a visual analogue to the feeling of being trapped with this unpredictable man when he literally fills the field of vision.

Perhaps what best amplifies The Plumber's feelings of horror and suspense, though, is something that brings us back to my initial point, about how Weir is a point where Ozploitation and the Australian New Wave meet up. Because this isn't, ultimately, a home invasion thriller, though it uses the form of one to get where it wants to go. Rather, the horror here is all purely psychological: it's about Jill's terrified realisation, from early on, that she's on her own against Max. As long as he's just tormenting her with vague innuendo and seemingly threatening anecdotes, she's physically safe, but it seems entirely possible that he might suddenly pounce on her at any moment, and she can neither predict when this will happen, nor do anything about it if it does. And as long as Max remains careful not to actually do anything other than continue to say unpleasant things, Jill has no recourse with the school, nor with her chauvinistically indifferent husband. It's certainly possible to take this farther than it can reasonably go - it's not a feminist message movie - but it is clear that Weir means for us to think of this in the context of the women's rights movements of the '70s: Jill isn't just a victim of the obnoxious, leering Max, but of a whole social order in which a man can get away with acting like this. That's the horror, rather than the specific fear of a specific thing Max might do.

It's still a film more interested in tightening its grip on our neck than in offering a statement of the state of the world, to be sure. This even ends up causing it some trouble, as it tries to motivate Max beyond "he's menacing": it suggests fairly early that he's motivated by class resentment, and then gives Jill a thoughtless rich friend Meg (Candy Raymond) who's an awkwardly-written caricature of absent-minded privilege, to show us the kind of mistreatment that he has presumably been enduring for some time. But this mostly ends up just cluttering things up: he's too well-motivated to work as a primordial, inexplicable threat, a vicious incarnation of the male id; but he's not well-motivated enough to ever have a trace of an inner life, and the film ends up suggesting, presumably by accident, that, well, the working class is just prone to this kind of brutish behavior, because they are our inferiors and don't know their place.

Still, it's not Max's film, it's Jill's, and if we step back from the social implications the film does (and maybe doesn't) want us to take away, there's still the matter of taking it as a simple little tale of a woman being made a nervous wreck from the threatening presence of a maniac who just shows up and won't go away. And it's pretty great at that, pressing on the gas steadily harder throughout its 77 minutes, making for a more and more claustrophobic. It's perhaps no more than an exercise in psychological tension, made by a director who had made it very clear that he was up for more than simple exercises; but it's a damn good exercise.

Body Count: 0, but the bathroom is in pretty bad shape by the time the movie wraps up.

This brings us, in turn, to the early work of Peter Weir, who would leave his home country in the 1980s to become the first veteran of the resurgent Australian film industry to make it as a major Hollywood director. That history begins mostly likely with 1981's Gallipoli, a handsomely-done historical epic made with middlebrow respectability, but in the preceding decade, Weir's career was much stranger: he made film after film straddling the line between Ozploitation and the new wave so cleanly that they raise the question of whether the line existed at all. 1974's The Cars That Ate Paris is exactly the film that it sounds like, but so aware of and in love with its own absurdity as to feel more intellectual than "the town kills people using evil cars" possibly could. Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave, from 1975 and 1977, have the plot hooks of by-the-books thrillers, and the pensive mood and dreamlike abstraction of the most visionary art film. And that brings us to 1979's television film The Plumber, the last thing Weir made prior to Gallipoli, and probably the closest of any of them to being a completely straightforward horror-thriller, though one made with exceptional control over tone and pacing, and with an explicit interest in thinking through the challenges associated with social change.

Like many of Weir's films, The Plumber is about people in a closed system, and the interpersonal conflicts that arise as a result. That is, indeed, the entire conflict of the movie: the unendurable stress of being in trapped in a flat with somebody who you would particularly not want to be trapped with. The flat belongs to the Cowpers, Jill (Judy Morris) and Brian (Robert Coleby); Brian is a professor at a school in Adelaide, and Jill was working on her degree before they moved to this city and she put that on hold to focus on homemaking. It's not clear how much of that was a mutual decision and how much was Brian leaning on her, but as the movie progresses, it becomes pretty clear that he's not very interested in her needs when they come into conflict with his. But that's not the big problem here. The big problem is that one morning, a man named Max (Ivar Kants) shows up, claiming to be a plumber sent by the university to do routine check-ups on the bathrooms in this block. She's not terribly thrilled by this, especially without having been made aware of this beforehand, but she lets him in anyway. If she was in our position, and could hear Gerry Tolland's score leaping up into a tense, bass-driven drone the minute that Max shows up, she would surely think better of that decision, but all that means is that we get to jump right into the film's thriller mechanics.

And such mechanics they are! The story is as simple as simple gets: Max comes in, flimflams Jill, and then proceeds to act in a tremendously creepy way while apparently destroying her bathroom rather than doing anything to fix it. When she mentions this to Brian, he brushes right by it, far more concerned with a possible World Health Organization grant that will give him a career-changing trip to Geneva; he even goes so far as to suggest that she's more stressed out about the possibility of that movie than by what she claims is stressing her out. The next day, the whole process repeats, and then again next day. Every time through, the tension spikes up, and the feeling of Jill's helpless terror intensifies, with Morris looking more worn out and frantic by the minute. This all plays out over just 77 minutes, a running time that focuses and intensifies the film's narrative considerably, making Max's repeated incursions into Jill's home all the more horrifying by making it feel like they're piling up on each other with break. He's always coming or going, it feels like, and by rushing through the story events so quickly, Weir (who wrote the script in addition to directing) exaggerates how Jill loses control of her own home, making it less like she's being bothered by Max, and more like she's under siege.

To accentuate this feeling of constant acceleration in the storytelling, Weir and cinematographer David Sanderson use the simplest tool in the box, but also one of the most effecive: shot scale. The Plumber was made for television, which means a television budget, which is probably one reason it has such a small number of location (the living room and the increasingly unusable bathroom in the Cowper's flat, plus a lecture hall, and a few scattered exteriors), and that has already had the good effect of limiting the film's ability to meander. Hence that intense 77-minute plunge into paranoia. But it also means that it was going to be shown on a physical television set (though it was given theatrical distribution outside of Australia). And that means that Weir and Sanderson had to move in close to their characters. Much of the film consists of dueling exchanges of close-ups, giving us ample room to take in Kants's nasty smirk and Morris's miserable, helpless reactions; it neatly creates a visual analogue to the feeling of being trapped with this unpredictable man when he literally fills the field of vision.

Perhaps what best amplifies The Plumber's feelings of horror and suspense, though, is something that brings us back to my initial point, about how Weir is a point where Ozploitation and the Australian New Wave meet up. Because this isn't, ultimately, a home invasion thriller, though it uses the form of one to get where it wants to go. Rather, the horror here is all purely psychological: it's about Jill's terrified realisation, from early on, that she's on her own against Max. As long as he's just tormenting her with vague innuendo and seemingly threatening anecdotes, she's physically safe, but it seems entirely possible that he might suddenly pounce on her at any moment, and she can neither predict when this will happen, nor do anything about it if it does. And as long as Max remains careful not to actually do anything other than continue to say unpleasant things, Jill has no recourse with the school, nor with her chauvinistically indifferent husband. It's certainly possible to take this farther than it can reasonably go - it's not a feminist message movie - but it is clear that Weir means for us to think of this in the context of the women's rights movements of the '70s: Jill isn't just a victim of the obnoxious, leering Max, but of a whole social order in which a man can get away with acting like this. That's the horror, rather than the specific fear of a specific thing Max might do.

It's still a film more interested in tightening its grip on our neck than in offering a statement of the state of the world, to be sure. This even ends up causing it some trouble, as it tries to motivate Max beyond "he's menacing": it suggests fairly early that he's motivated by class resentment, and then gives Jill a thoughtless rich friend Meg (Candy Raymond) who's an awkwardly-written caricature of absent-minded privilege, to show us the kind of mistreatment that he has presumably been enduring for some time. But this mostly ends up just cluttering things up: he's too well-motivated to work as a primordial, inexplicable threat, a vicious incarnation of the male id; but he's not well-motivated enough to ever have a trace of an inner life, and the film ends up suggesting, presumably by accident, that, well, the working class is just prone to this kind of brutish behavior, because they are our inferiors and don't know their place.

Still, it's not Max's film, it's Jill's, and if we step back from the social implications the film does (and maybe doesn't) want us to take away, there's still the matter of taking it as a simple little tale of a woman being made a nervous wreck from the threatening presence of a maniac who just shows up and won't go away. And it's pretty great at that, pressing on the gas steadily harder throughout its 77 minutes, making for a more and more claustrophobic. It's perhaps no more than an exercise in psychological tension, made by a director who had made it very clear that he was up for more than simple exercises; but it's a damn good exercise.

Body Count: 0, but the bathroom is in pretty bad shape by the time the movie wraps up.

Categories: horror, oz/kiwi cinema, summer of blood, television, thrillers