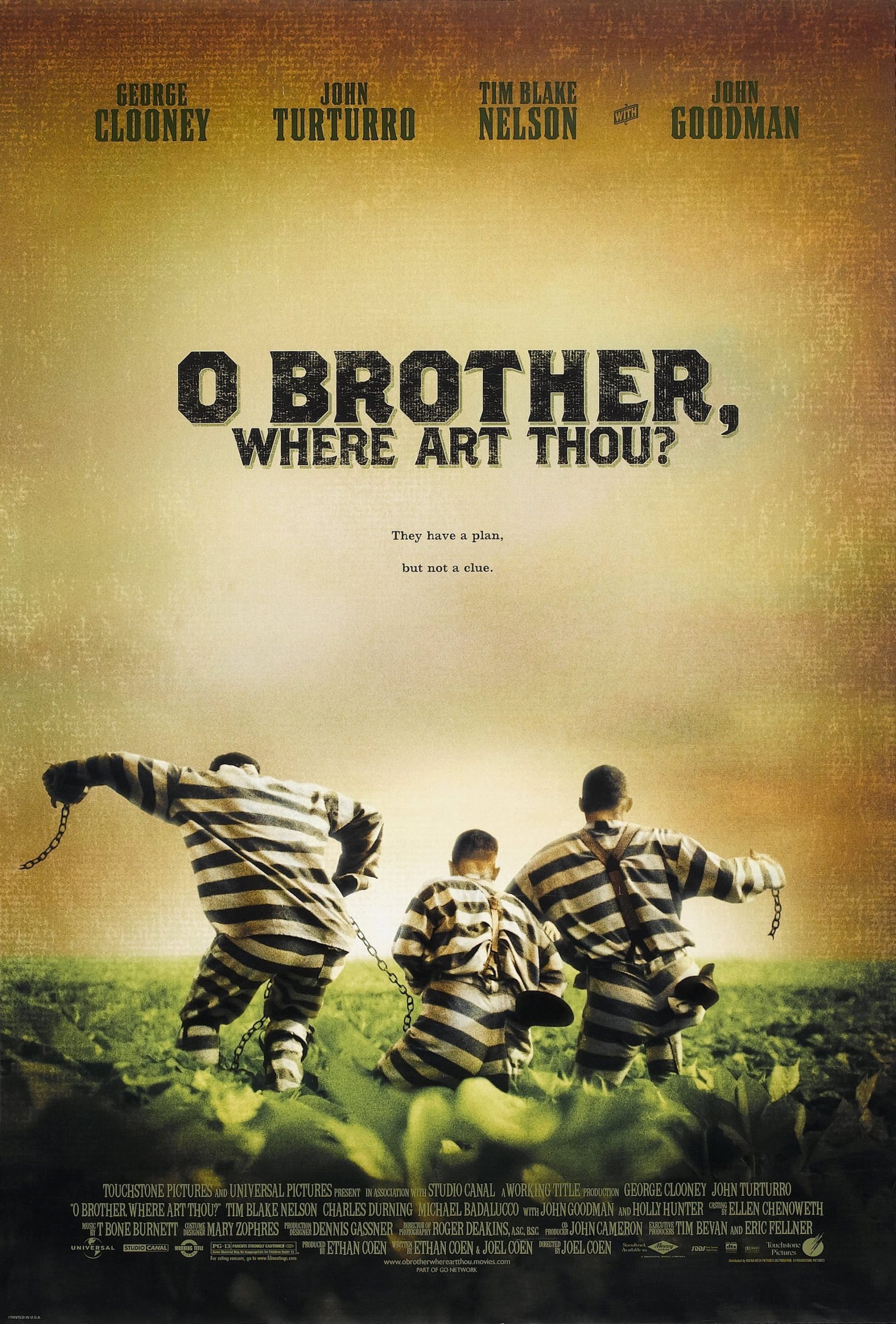

Hot damn! It's the Soggy Bottom Boys!

The eighth film made by Joel & Ethan Coen, 2000's O Brother, Where Art Thou? also has the distinction of being their first full-on no-two-ways-about-it major studio production. 20th Century Fox had distributed Raising Arizona, Miller's Crossing, and Barton Fink, but the financing and production of those films was still closer to a conventional indie model. Joel Silver's Silver Pictures had paid for most of The Hudsucker Proxy, and that's certainly getting us close enough to the idea of "a major studio production" that it's not worth splitting hairs; but there's a sense in looking at the history of that film's production that Silver was spending money that he knew he wasn't going to get back, just for the pleasure of being in the Coen brothers business. O Brother, meanwhile, was a co-production between Disney's Touchstone Pictures, Universal Pictures, and StudioCanal, presumably looking to see what they could make out of two of the hottest auteurs in the United States after the success of Fargo in 1996.

One hesitates to put more weight on this than it can bear - it does not seem, at any rate, that O Brother was buried under executive notes, or even had much in the way of executive oversight - but it's hard not to extrapolate. One important thing to note is that, from this point onward, the brothers' budgets would explode. Of their first seven films, The Hudsucker Proxy was the only one that cost "studio movie" money (O Brother had roughly the same budget as that film); going forward, their only two "cheap" movies would be A Serious Man in 2009 and Inside Llewyn Davis in 2013, and this seems to be underappreciated as an important break in their filmography. Everybody knows that No Country for Old Men started the Coen Renaissance in 2007, but the break between scrappy indies and well-heeled studio films is probably just as important, particularly as the filmmakers became more and more invested in the top-to-bottom construction of entire worlds, courtesy of costume designer Mary Zophres (who'd been with them since Fargo in 1996) and set decorator Nancy Haigh (who'd been with them since Miller's Crossing in 1990), and ultimately production designer Jess Gonchor (who'd join their merry band with No Country). Of course, Hudsucker started that process, but O Brother is where it becomes a dominant aspect of their style.

Using O Brother as a major break in the Coens' filmography is helpful for another reason: it kicks off a half-decade of steady decline, as the two men who were among the most ingenious and creative American filmmakers of the 1990s seemed to suddenly lose track of what they were doing and why. O Brother is not, by any means, a "bad" movie - it is, after all, at the start of that slope. But is the first Coen movie, and I include The Hudsucker Proxy here, that leaves me with the reaction "well, that didn't quite come together, did it?" And I do not know how much we can blame this on the increasing budgets, or any other one thing, but it certainly feels like the problem that sometimes happens when filmmakers suddenly get all the resources they need: when there's no need to focus, it becomes rather hard to do so.

But let me not get all doomy and gloomy yet. O Brother is still a film of many extraordinarily wonderful ingredients, and on a scene-by-scene basis, it has some of the richest world-building in the filmmakers' career to that point. The official line is that this is an adaptation of Homer's Odyssey (something we're told right in the opening credits - another break! This is the first Coen movie whose opening credits list anything other than the cast and the title. And yes, that does feel to me like it matters), but as the Coens revealed fairly early on in the promotional tour, neither of them had ever read it, and were just using the basic idea that everybody has about what goes into The Odyssey as the basis for a picaresque tale of the American South in the Great Depression. I suspect this is why O Brother feels so much more like a collection of scenes than an overall narrative: when you approach the act of writing from the perspective, "well, we need sirens, and a cyclops, and lotus eaters..." it's going to be natural to end a series of anecdotes rather than a story. This is, after a fashion, how The Odyssey itself worked.

Far more than it owes to Homer, though, O Brother is drawing from the big, messy patchwork called "Americana": it grabs concepts from American folklore, American political mythology, and American folk music. And this honestly feels like the most honest way to adapt The Odyssey anyways: that was, after all, the written-down version of stories in an oral tradition, and to an extent, O Brother works the same way. It is self-consciously mythic, treating Mississippi in the 1930s - a place and time that existed comfortably within living memory in 2000 - as a fairy tale world, both in terms of what happens and in terms of how it's visually presented.

And, of course, they were drawing from their beloved (and all our beloved) Preston Sturges, the great writer-director of some of the best comedies of the WWII era, particularly his Sullivan's Travels from 1941. In that film, Joel McCrea plays John Sullivan, a film director very much like Sturges who is sick and tired of making lightweight comedies that pretend that the world isn't in a state of tremendous upheaval, and dreams of making a heavy, earnest social issues epic named O Brother, Where Art Thou? Over the course of his journey across the country, trying to research the miseries of poverty, he finds that the people he wants to commemorate do not like heavy "serious" art, and that a really good wacky comedy can do more to lift the human soul and reinstate a sense of dignity into the lives of the dispossessed than all the message movies put together. The Coens' O Brother isn't at all the film that Sullivan wanted to make, but it is still their own attempt to pay tribute to the lives of the broken-down and helpless during the Depression, but without ever losing sight of Sturges's lesson that audiences would rather laugh than cry.

That is three different "what the film is, primarily" stories, and that might help to explain a little bit about why O Brother ends up feeling scattered. It's a movie with no lack of ideas, and no real strategy for stitching them together. This is as broad at the level of the film's whole story, which starts off as the tale of three men who escape from a chain gang together, Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney), Pete Hogwallop (John Turturro), and Delmar O'Donnell (Tim Blake Nelson), so that they can find a million dollars that Everett buried in a valley that is, by the end of the week, going to be under a whole lot of water once a dam is completed. Midway through, we find out that this was a lie told solely because Everett needed to motivate Pete and Delmar to escape: the actual ticking clock is that his wife Penny (Holly Hunter), having told their children that he died and divorced him in shame, is about to get re-married, and he wants to put a stop to it. And of course that's the plot, given that this is The Odyssey, but the big difference is that Homer never says otherwise, while we learn about Penny sort of messily in the middle of the film, at which point it more or less completely restarts.

And it can be as specific as who our characters are. Everett is a great part for Clooney, who was at that point broadly understood to be a handsome but somewhat uninteresting TV actor whose looks were good enough to get him movie roles, but not enough to make him interesting to watch, notwithstanding Steven Soderbergh's sexy and stylish comedy-thriller Out of Sight. In all of the Coens' years of looking at under-utilised character actors and figuring out exactly what to do with them, I can't name a single example of casting more counter-intuitively insightful than recognising that the right thing to do with this bland handsome man was to cast him as a cartoon imbecile. Clooney's career would have still turned out fine - the Soderbergh connection means that he would have gotten Ocean's Eleven regardless, and Ocean's Eleven is what actually kick-started his second movie career as the most charismatic, classy motherfucker in Hollywood - but without this, I wonder if we'd have ever discovered that he could actually be fun. And it's probably not a coincidence that in two of their three subsequent collaborations, the brothers once again cast him as a blithering moron.

So yes, Clooney's delightful, in a delightful part. But it's an erratically-conceived part. Depending on the needs of the moment, Everett can be anything from a wise-cracking Clark Gable type, smart enough to outthink everybody else even if he's not always able to turn that to his advantage, to just as dumb as Pete and Delmar, but able to talk fast enough to make it seem otherwise. At one point, he cheerfully watches as one of his colleagues is clubbed into a coma, and doesn't realise anything's wrong. This is not a consistent character - he is what the scene needs him to be, no more and no less, and while Clooney is always extremely good at playing the scene with comic gusto, he's not even trying to help the script shape this all into a single characterisation.

All that being said, I don't want to leave the impression that I don't like O Brother - for all its limitations and the places where it feels like half a movie, that half is absolutely hilarious. The film is basically a live-action cartoon, asking the large cast to commit to playing broad stereotypes: the Coens have always loved playing with dialect, but this seems to me to be their one and only dialect comedy, in which the fact that people in the South talk funny is itself part of the joke (if you agree with me that the dialogue in Fargo is more about characterisation than humor necessarily). And there's more to it than just that: Turturro and Nelson (the latter a superb addition to the Coen stock company, and I hate that it took 18 years for them to collaborate again) hold nothing back in turning themselves into rubber-limbed buffoons who'd fit into a Bugs Bunny cartoon better than the real world. Hell, the funniest gag of the entire movie, to me, is just watching Turturro do a bizarre Charleston-like dance, out-of-focus in the background, where his knees appear to be melting.

Still, dialogue in all its forms is the main thrust of the humor: Everett's sharp-tongued flimflam routine, Charles Durning's irritable patrician bellowing, in his second and (alas!) final Coen film, John Goodman's more loquacious and almost unmanageable curlicues of phrase as Everett's evil twin, Hunter's machine-gun firing of short jabs at Clooney. One gets the impression that part of the reason the story doesn't quite hang together is that the writers were having too much fun simply marinating in all their different gradations of Southern-fried prattle, and it's just as pleasurable to listen to, as every character speaks with their own distinctive cadence.

As well-done as this is in its caricatured excess, the surprising thing about O Brother, and maybe the reason I still like it quite a lot despite its missteps, is that broad comedy is only part of it. It's also a weirdly sad, even morbid film. It's a type of musical I mentioned, with several moments where folk and bluegrass performances take over the film: it was made in collaboration with T Bone Burnett, who curated and produced the film's massively successful soundtrack, and one feels like he almost deserves to be credited as co-director. Almost every scene eventually involves music, and the successful resolution of the plot hinges on the fact that our heroes at one point disguised themselves as the "Soggy Bottom Boys" (along with a Robert Johnson surrogate played by New Orleans blues musician Chris Thomas King) and inadvertently recorded a smash hit record. The political election battle that doesn't help to structure the film's second half nearly as much as the film wants it to (though it does give Durning one fantastic scene after another) is in large part a war of old-timey music. And the fascinating thing about this music is how much of it is, like, sad: even some of the uplifting music, like the spiritual "Down to the River to Pray", has a downbeat, melancholy tone. There is a sense in the soundrack of weariness and the coming rush of death that cuts against the warped humor without ever feeling faked.

And that sense is even stronger in the cinematography by Roger Deakins, which is almost without question the most important work of his career. The entirety of O Brother was scanned into a computer and re-colored digitally before being recorded back on film, a process known as "digital intermediate"; this was the first film to undergo that process, which became ubiquitous within the industry over the following decade, and led directly into the workflow that allowed digital cinematography to take over around 2012. But I'm not blaming Deakins for that. My point is that, using this technique, he turned the verdant greens of the original footage in to a dried-out, sun-baked husk, with everything baked in a veneer of hot yellows and golds (except for one crucial scene near the end, where it's cool and blue, and the contrast is gut-wrenching). O Brother takes place in a world where summer is ending and autumn is coming, and pretty much everything feels caked in dust and bereft of hope and life. That is the thing that unifies the film, if anything does: the profound mood that Deakins impresses upon it. And, again, this doesn't break the wacky comic tone, which is something of a miracle really; because the film looks exhausted. What, if anything, that exhaustion has to do with the content of the plot, or the Great Depression writ large, I cannot quite say, but it does shoot the whole film through with a feeling of brooding, understated despair, and if anything keeps this weightless, shapeless film feeling like a cohesive object, that undercurrent is what does it.

One hesitates to put more weight on this than it can bear - it does not seem, at any rate, that O Brother was buried under executive notes, or even had much in the way of executive oversight - but it's hard not to extrapolate. One important thing to note is that, from this point onward, the brothers' budgets would explode. Of their first seven films, The Hudsucker Proxy was the only one that cost "studio movie" money (O Brother had roughly the same budget as that film); going forward, their only two "cheap" movies would be A Serious Man in 2009 and Inside Llewyn Davis in 2013, and this seems to be underappreciated as an important break in their filmography. Everybody knows that No Country for Old Men started the Coen Renaissance in 2007, but the break between scrappy indies and well-heeled studio films is probably just as important, particularly as the filmmakers became more and more invested in the top-to-bottom construction of entire worlds, courtesy of costume designer Mary Zophres (who'd been with them since Fargo in 1996) and set decorator Nancy Haigh (who'd been with them since Miller's Crossing in 1990), and ultimately production designer Jess Gonchor (who'd join their merry band with No Country). Of course, Hudsucker started that process, but O Brother is where it becomes a dominant aspect of their style.

Using O Brother as a major break in the Coens' filmography is helpful for another reason: it kicks off a half-decade of steady decline, as the two men who were among the most ingenious and creative American filmmakers of the 1990s seemed to suddenly lose track of what they were doing and why. O Brother is not, by any means, a "bad" movie - it is, after all, at the start of that slope. But is the first Coen movie, and I include The Hudsucker Proxy here, that leaves me with the reaction "well, that didn't quite come together, did it?" And I do not know how much we can blame this on the increasing budgets, or any other one thing, but it certainly feels like the problem that sometimes happens when filmmakers suddenly get all the resources they need: when there's no need to focus, it becomes rather hard to do so.

But let me not get all doomy and gloomy yet. O Brother is still a film of many extraordinarily wonderful ingredients, and on a scene-by-scene basis, it has some of the richest world-building in the filmmakers' career to that point. The official line is that this is an adaptation of Homer's Odyssey (something we're told right in the opening credits - another break! This is the first Coen movie whose opening credits list anything other than the cast and the title. And yes, that does feel to me like it matters), but as the Coens revealed fairly early on in the promotional tour, neither of them had ever read it, and were just using the basic idea that everybody has about what goes into The Odyssey as the basis for a picaresque tale of the American South in the Great Depression. I suspect this is why O Brother feels so much more like a collection of scenes than an overall narrative: when you approach the act of writing from the perspective, "well, we need sirens, and a cyclops, and lotus eaters..." it's going to be natural to end a series of anecdotes rather than a story. This is, after a fashion, how The Odyssey itself worked.

Far more than it owes to Homer, though, O Brother is drawing from the big, messy patchwork called "Americana": it grabs concepts from American folklore, American political mythology, and American folk music. And this honestly feels like the most honest way to adapt The Odyssey anyways: that was, after all, the written-down version of stories in an oral tradition, and to an extent, O Brother works the same way. It is self-consciously mythic, treating Mississippi in the 1930s - a place and time that existed comfortably within living memory in 2000 - as a fairy tale world, both in terms of what happens and in terms of how it's visually presented.

And, of course, they were drawing from their beloved (and all our beloved) Preston Sturges, the great writer-director of some of the best comedies of the WWII era, particularly his Sullivan's Travels from 1941. In that film, Joel McCrea plays John Sullivan, a film director very much like Sturges who is sick and tired of making lightweight comedies that pretend that the world isn't in a state of tremendous upheaval, and dreams of making a heavy, earnest social issues epic named O Brother, Where Art Thou? Over the course of his journey across the country, trying to research the miseries of poverty, he finds that the people he wants to commemorate do not like heavy "serious" art, and that a really good wacky comedy can do more to lift the human soul and reinstate a sense of dignity into the lives of the dispossessed than all the message movies put together. The Coens' O Brother isn't at all the film that Sullivan wanted to make, but it is still their own attempt to pay tribute to the lives of the broken-down and helpless during the Depression, but without ever losing sight of Sturges's lesson that audiences would rather laugh than cry.

That is three different "what the film is, primarily" stories, and that might help to explain a little bit about why O Brother ends up feeling scattered. It's a movie with no lack of ideas, and no real strategy for stitching them together. This is as broad at the level of the film's whole story, which starts off as the tale of three men who escape from a chain gang together, Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney), Pete Hogwallop (John Turturro), and Delmar O'Donnell (Tim Blake Nelson), so that they can find a million dollars that Everett buried in a valley that is, by the end of the week, going to be under a whole lot of water once a dam is completed. Midway through, we find out that this was a lie told solely because Everett needed to motivate Pete and Delmar to escape: the actual ticking clock is that his wife Penny (Holly Hunter), having told their children that he died and divorced him in shame, is about to get re-married, and he wants to put a stop to it. And of course that's the plot, given that this is The Odyssey, but the big difference is that Homer never says otherwise, while we learn about Penny sort of messily in the middle of the film, at which point it more or less completely restarts.

And it can be as specific as who our characters are. Everett is a great part for Clooney, who was at that point broadly understood to be a handsome but somewhat uninteresting TV actor whose looks were good enough to get him movie roles, but not enough to make him interesting to watch, notwithstanding Steven Soderbergh's sexy and stylish comedy-thriller Out of Sight. In all of the Coens' years of looking at under-utilised character actors and figuring out exactly what to do with them, I can't name a single example of casting more counter-intuitively insightful than recognising that the right thing to do with this bland handsome man was to cast him as a cartoon imbecile. Clooney's career would have still turned out fine - the Soderbergh connection means that he would have gotten Ocean's Eleven regardless, and Ocean's Eleven is what actually kick-started his second movie career as the most charismatic, classy motherfucker in Hollywood - but without this, I wonder if we'd have ever discovered that he could actually be fun. And it's probably not a coincidence that in two of their three subsequent collaborations, the brothers once again cast him as a blithering moron.

So yes, Clooney's delightful, in a delightful part. But it's an erratically-conceived part. Depending on the needs of the moment, Everett can be anything from a wise-cracking Clark Gable type, smart enough to outthink everybody else even if he's not always able to turn that to his advantage, to just as dumb as Pete and Delmar, but able to talk fast enough to make it seem otherwise. At one point, he cheerfully watches as one of his colleagues is clubbed into a coma, and doesn't realise anything's wrong. This is not a consistent character - he is what the scene needs him to be, no more and no less, and while Clooney is always extremely good at playing the scene with comic gusto, he's not even trying to help the script shape this all into a single characterisation.

All that being said, I don't want to leave the impression that I don't like O Brother - for all its limitations and the places where it feels like half a movie, that half is absolutely hilarious. The film is basically a live-action cartoon, asking the large cast to commit to playing broad stereotypes: the Coens have always loved playing with dialect, but this seems to me to be their one and only dialect comedy, in which the fact that people in the South talk funny is itself part of the joke (if you agree with me that the dialogue in Fargo is more about characterisation than humor necessarily). And there's more to it than just that: Turturro and Nelson (the latter a superb addition to the Coen stock company, and I hate that it took 18 years for them to collaborate again) hold nothing back in turning themselves into rubber-limbed buffoons who'd fit into a Bugs Bunny cartoon better than the real world. Hell, the funniest gag of the entire movie, to me, is just watching Turturro do a bizarre Charleston-like dance, out-of-focus in the background, where his knees appear to be melting.

Still, dialogue in all its forms is the main thrust of the humor: Everett's sharp-tongued flimflam routine, Charles Durning's irritable patrician bellowing, in his second and (alas!) final Coen film, John Goodman's more loquacious and almost unmanageable curlicues of phrase as Everett's evil twin, Hunter's machine-gun firing of short jabs at Clooney. One gets the impression that part of the reason the story doesn't quite hang together is that the writers were having too much fun simply marinating in all their different gradations of Southern-fried prattle, and it's just as pleasurable to listen to, as every character speaks with their own distinctive cadence.

As well-done as this is in its caricatured excess, the surprising thing about O Brother, and maybe the reason I still like it quite a lot despite its missteps, is that broad comedy is only part of it. It's also a weirdly sad, even morbid film. It's a type of musical I mentioned, with several moments where folk and bluegrass performances take over the film: it was made in collaboration with T Bone Burnett, who curated and produced the film's massively successful soundtrack, and one feels like he almost deserves to be credited as co-director. Almost every scene eventually involves music, and the successful resolution of the plot hinges on the fact that our heroes at one point disguised themselves as the "Soggy Bottom Boys" (along with a Robert Johnson surrogate played by New Orleans blues musician Chris Thomas King) and inadvertently recorded a smash hit record. The political election battle that doesn't help to structure the film's second half nearly as much as the film wants it to (though it does give Durning one fantastic scene after another) is in large part a war of old-timey music. And the fascinating thing about this music is how much of it is, like, sad: even some of the uplifting music, like the spiritual "Down to the River to Pray", has a downbeat, melancholy tone. There is a sense in the soundrack of weariness and the coming rush of death that cuts against the warped humor without ever feeling faked.

And that sense is even stronger in the cinematography by Roger Deakins, which is almost without question the most important work of his career. The entirety of O Brother was scanned into a computer and re-colored digitally before being recorded back on film, a process known as "digital intermediate"; this was the first film to undergo that process, which became ubiquitous within the industry over the following decade, and led directly into the workflow that allowed digital cinematography to take over around 2012. But I'm not blaming Deakins for that. My point is that, using this technique, he turned the verdant greens of the original footage in to a dried-out, sun-baked husk, with everything baked in a veneer of hot yellows and golds (except for one crucial scene near the end, where it's cool and blue, and the contrast is gut-wrenching). O Brother takes place in a world where summer is ending and autumn is coming, and pretty much everything feels caked in dust and bereft of hope and life. That is the thing that unifies the film, if anything does: the profound mood that Deakins impresses upon it. And, again, this doesn't break the wacky comic tone, which is something of a miracle really; because the film looks exhausted. What, if anything, that exhaustion has to do with the content of the plot, or the Great Depression writ large, I cannot quite say, but it does shoot the whole film through with a feeling of brooding, understated despair, and if anything keeps this weightless, shapeless film feeling like a cohesive object, that undercurrent is what does it.