Australian Winter of Blood: Hello, nurse

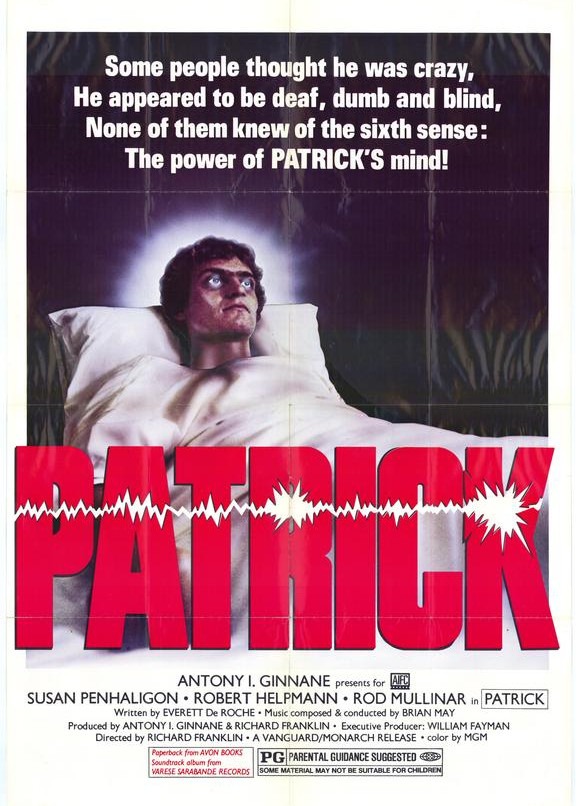

We come now to an exciting moment: the first appearance on this site (but by no means the last) of two of the most significant names in Australian horror around the end of the '70s and the beginning of the '80s, director Richard Franklin and screenwriter Everett De Roche, whose names are attached to some of the genre's most well-regarded titles. For that matter, our present subject, Patrick is itself a film of no small esteem and importance: it was one of the first major hit exports of '70s Ozploitation, and among the first to demonstrate that Australian genre films could compete on the international market. Indeed, it did rather noticeably better abroad than in its home country, bringing us to one of the most excitingly cynical points in the development of any nation's film industry: the moment that its producers start to think about how they can get their projects a good-sized release in the United States. Now, I'm not saying that you can draw a straight line from Patrick to Crocodile Dundee, or something silly like that. But you can draw a crooked line.

For that matter, Patrick was already borrowing from the United States. Given the film's release date and subject matter, it's awfully hard not to think of it as a knock-off of the 1976 American film Carrie, a film whose success spawned a decent number of imitators, though not entire cottage industries of copycats like The Exorcist or Jaws. But there are knock-offs and there are knock-offs, and just because it's hard to imagine this story of a violently psychokinetic young adult getting funded without that story of a violently psychokinetic having proven there was a taste for such things, doesn't mean that Patrick isn't doing a pretty great job of making its own way in the world, free from any undue influence of Ms. White and her extremely bad prom night.

For starters, Patrick himself (Robert Thompson) is never seen as anything but the villain, right from the very start, when we meet him as a staring, moody teen - and I do mean staring, the film's very first image is a close-up on his unpleasantly unwavering & unblinking eye - listening with dull contempt as his mother (Carole-Ann Aylett) is loudly having sex with with her current boyfriend (Paul Young), banging the headboard of her bed in a rhythmic thunk against the shared wall with Patrick's own bedroom (the split-screen showing the bedpost smacking against the back of his head is a slightly corny but unnervingly successful visual flourish in a film that will be, ultimately, relatively light on visual flourishes). Sometime later, as the lovers have taken things to the bathtub, he arrives with a plugged in space heater: he tosses it as his mother, badly burning her before it falls into the water, killing them both.

And then we are hustled right along to three years later, where Kathy Jacquard (Susan Penhaligon), a recent transplant to this part of the world, is interviewing with an extremely hostile head nurse, Matron Cassidy (Julia Blake). Cassidy's openly contemptuous, judgmental questions let us learn that Kathy is separated from her husband Ed (Rod Mollinar), and it looks like it's heading towards divorce; the older woman plainly supposes that this means that Kathy is one of those awful "new women" who'll abandon her job just as bullishly as she's abandoned her husband, and it's only the desperate need for warm bodies with nursing skills that causes her to offer Kathy even a probationary position at this tiny hospital. The star patient, and Kathy's main job, is none other than Patrick himself, who immediately lapsed into a coma after killing his mother, and the cops have assumed as a result that he merely found the bodies and went into shock. Three years later, Patrick seems as good as dead, with no apparent brain activity, and a simply horrifying refusal to keep his eyes shut, meaning that the nursing staff is obliged to keep his eyeballs moist. This whole situation delights Dr. Roget (Robert Helpmann), the owner of the hospital, who think that Patrick's bizarre case (his body is unusually healthy, even more fit than when he was admitted, so when he dies, it will be of brain death, not of physical wasting) makes him the perfect case to test the doctor's very poetic and off-putting theories about the death process.

In this environment, it takes absolutely no effort to be the kindest person to Patrick, and sure enough, Kathy is. Given that despite all the available evidence, the patient is in fact quite alert and somehow aware of his environment, despite being able to neither see nor feel, this naturally means that he's going to crush on the pretty young nurse, and hard. Given that he's a murderous psychopath whose condition has apparently triggered telekinetic abilities, this crush is going to go extremely poorly for her, and anybody who tries to keep her away from him, be it the hostile Cassidy, the possessive Ed, or the arrogant Brian Wright (Bruce Barry), the handsome doctor that Kathy gets set up with by a coworker, who'll be on the receiving end on the first odd little moment that seems like nothing to everybody but us.

This could easily be a fine telekinesis thriller, but Franklin and De Roche have more in mind than just pushing our buttons. Following the logic that the best way to make us feel sympathy for the victim of a horror movie monster is to give that victim a full and relatable personality, they've gone all-in on making Kathy a complex and interesting protagonist, and Penhaligon is entirely up for the task of helping to deepen her character. In a weird way, the hook of Patrick isn't the telekinetic coma patient; it's that he's only one of several crises rushing towards Kathy at top speed. Her job precarity in a country she's implied to not know very well at all is an obvious point of tension, and so is her relationship with Ed, a crude asshole who thinks nothing of breaking into the home where she's been living during their trial separation to try and whine his way into having her come back. Brian is at least better than that on the surface, but he's also clearly not wanting for ego. She is, in short, a woman dealing with far too much already before she figures out that there's something more than meets with the eye with her strange patient, the one that the whole rest of the hospital seems to be mildly terrified by.

Lord knows Patrick isn't the first high-concept horror movie to present itself as a domestic drama and character study, but it's quite good at it; so good, in fact, that even as it remains unambiguously a horror movie - we know that Patrick is no good early enough that while Kathy is still fascinated by his unexpected awareness and is still in "good nurse fighting for her patient" mode, we're all tensed up and concerned, and Franklin helps that along by using a lot of overly-snug close-ups to make us feel hyper-aware of small details - there's a sense in which Kathy's character arc matter more than jolts and scares. The climax, which is built around her psychological toughness, is the clearest indication that this is more a story about her growth and self-reliance than her ability to survive a lunatic who can not only throw objects at people, but also briefly take over their minds - as he does to her, multiple times, to make her type out messages from him, in one of the places that the film uses those close-ups to freak us out before there's anything explicit to be freaked out by. Penhaligon plays Kathy this climax as being, above all else, calm as she stares down Patrick, treating it as a character beat rather than an action beat. It's unexpected, but also somehow inevitable.

The treatment of Kathy is certainly a highlight, if not the actively strongest part of Patrick, but this is in general a very well-made movie. I have mentioned that it is light on visual flourishes, but they do exist: there's a neon sign outside Patrick's room that is used sporadically to create bold swatches of red and blue, almost expressionistic in the way they privilege the creation of an emotion over anything else. It's one of the few ways in which Patrick tries to build any kind of foreboding atmosphere, but part of why it works is that it's so unusual, and that those moments, and Patrick's unreadable expression in those moments, thus seem to have more weight.

It is a bit on the long side, at 112 minutes, and with not all that many plot points to cover in that time; this is undoubtedly so it can create a slow burn while Kathy gets herself in over her head, but that's a tricky game to play when the audience does not merely suspect, but in fact knows outright what's going on, and it doesn't help that things never actually speed up. She spends an awful lot of time trying to convince other people of Patrick's skills, in a series of scenes that mostly reiterate what we already know about how lousy everybody in her life is. Still, when a horror movie slows down to take time for character moments, and the main character can actually support that? That's when you know you have something rare and impressive and special, and for all that it's ultimately just a quick low-budget shocker, it's amazing how thoughtful Patrick manages to be.

Body Count: The ending is just ambiguous enough to put it in doubt, but the safe money is on 3, plus two frogs whose deaths appear to be somewhat less faked than I'm sure we'd all prefer.

For that matter, Patrick was already borrowing from the United States. Given the film's release date and subject matter, it's awfully hard not to think of it as a knock-off of the 1976 American film Carrie, a film whose success spawned a decent number of imitators, though not entire cottage industries of copycats like The Exorcist or Jaws. But there are knock-offs and there are knock-offs, and just because it's hard to imagine this story of a violently psychokinetic young adult getting funded without that story of a violently psychokinetic having proven there was a taste for such things, doesn't mean that Patrick isn't doing a pretty great job of making its own way in the world, free from any undue influence of Ms. White and her extremely bad prom night.

For starters, Patrick himself (Robert Thompson) is never seen as anything but the villain, right from the very start, when we meet him as a staring, moody teen - and I do mean staring, the film's very first image is a close-up on his unpleasantly unwavering & unblinking eye - listening with dull contempt as his mother (Carole-Ann Aylett) is loudly having sex with with her current boyfriend (Paul Young), banging the headboard of her bed in a rhythmic thunk against the shared wall with Patrick's own bedroom (the split-screen showing the bedpost smacking against the back of his head is a slightly corny but unnervingly successful visual flourish in a film that will be, ultimately, relatively light on visual flourishes). Sometime later, as the lovers have taken things to the bathtub, he arrives with a plugged in space heater: he tosses it as his mother, badly burning her before it falls into the water, killing them both.

And then we are hustled right along to three years later, where Kathy Jacquard (Susan Penhaligon), a recent transplant to this part of the world, is interviewing with an extremely hostile head nurse, Matron Cassidy (Julia Blake). Cassidy's openly contemptuous, judgmental questions let us learn that Kathy is separated from her husband Ed (Rod Mollinar), and it looks like it's heading towards divorce; the older woman plainly supposes that this means that Kathy is one of those awful "new women" who'll abandon her job just as bullishly as she's abandoned her husband, and it's only the desperate need for warm bodies with nursing skills that causes her to offer Kathy even a probationary position at this tiny hospital. The star patient, and Kathy's main job, is none other than Patrick himself, who immediately lapsed into a coma after killing his mother, and the cops have assumed as a result that he merely found the bodies and went into shock. Three years later, Patrick seems as good as dead, with no apparent brain activity, and a simply horrifying refusal to keep his eyes shut, meaning that the nursing staff is obliged to keep his eyeballs moist. This whole situation delights Dr. Roget (Robert Helpmann), the owner of the hospital, who think that Patrick's bizarre case (his body is unusually healthy, even more fit than when he was admitted, so when he dies, it will be of brain death, not of physical wasting) makes him the perfect case to test the doctor's very poetic and off-putting theories about the death process.

In this environment, it takes absolutely no effort to be the kindest person to Patrick, and sure enough, Kathy is. Given that despite all the available evidence, the patient is in fact quite alert and somehow aware of his environment, despite being able to neither see nor feel, this naturally means that he's going to crush on the pretty young nurse, and hard. Given that he's a murderous psychopath whose condition has apparently triggered telekinetic abilities, this crush is going to go extremely poorly for her, and anybody who tries to keep her away from him, be it the hostile Cassidy, the possessive Ed, or the arrogant Brian Wright (Bruce Barry), the handsome doctor that Kathy gets set up with by a coworker, who'll be on the receiving end on the first odd little moment that seems like nothing to everybody but us.

This could easily be a fine telekinesis thriller, but Franklin and De Roche have more in mind than just pushing our buttons. Following the logic that the best way to make us feel sympathy for the victim of a horror movie monster is to give that victim a full and relatable personality, they've gone all-in on making Kathy a complex and interesting protagonist, and Penhaligon is entirely up for the task of helping to deepen her character. In a weird way, the hook of Patrick isn't the telekinetic coma patient; it's that he's only one of several crises rushing towards Kathy at top speed. Her job precarity in a country she's implied to not know very well at all is an obvious point of tension, and so is her relationship with Ed, a crude asshole who thinks nothing of breaking into the home where she's been living during their trial separation to try and whine his way into having her come back. Brian is at least better than that on the surface, but he's also clearly not wanting for ego. She is, in short, a woman dealing with far too much already before she figures out that there's something more than meets with the eye with her strange patient, the one that the whole rest of the hospital seems to be mildly terrified by.

Lord knows Patrick isn't the first high-concept horror movie to present itself as a domestic drama and character study, but it's quite good at it; so good, in fact, that even as it remains unambiguously a horror movie - we know that Patrick is no good early enough that while Kathy is still fascinated by his unexpected awareness and is still in "good nurse fighting for her patient" mode, we're all tensed up and concerned, and Franklin helps that along by using a lot of overly-snug close-ups to make us feel hyper-aware of small details - there's a sense in which Kathy's character arc matter more than jolts and scares. The climax, which is built around her psychological toughness, is the clearest indication that this is more a story about her growth and self-reliance than her ability to survive a lunatic who can not only throw objects at people, but also briefly take over their minds - as he does to her, multiple times, to make her type out messages from him, in one of the places that the film uses those close-ups to freak us out before there's anything explicit to be freaked out by. Penhaligon plays Kathy this climax as being, above all else, calm as she stares down Patrick, treating it as a character beat rather than an action beat. It's unexpected, but also somehow inevitable.

The treatment of Kathy is certainly a highlight, if not the actively strongest part of Patrick, but this is in general a very well-made movie. I have mentioned that it is light on visual flourishes, but they do exist: there's a neon sign outside Patrick's room that is used sporadically to create bold swatches of red and blue, almost expressionistic in the way they privilege the creation of an emotion over anything else. It's one of the few ways in which Patrick tries to build any kind of foreboding atmosphere, but part of why it works is that it's so unusual, and that those moments, and Patrick's unreadable expression in those moments, thus seem to have more weight.

It is a bit on the long side, at 112 minutes, and with not all that many plot points to cover in that time; this is undoubtedly so it can create a slow burn while Kathy gets herself in over her head, but that's a tricky game to play when the audience does not merely suspect, but in fact knows outright what's going on, and it doesn't help that things never actually speed up. She spends an awful lot of time trying to convince other people of Patrick's skills, in a series of scenes that mostly reiterate what we already know about how lousy everybody in her life is. Still, when a horror movie slows down to take time for character moments, and the main character can actually support that? That's when you know you have something rare and impressive and special, and for all that it's ultimately just a quick low-budget shocker, it's amazing how thoughtful Patrick manages to be.

Body Count: The ending is just ambiguous enough to put it in doubt, but the safe money is on 3, plus two frogs whose deaths appear to be somewhat less faked than I'm sure we'd all prefer.