Every time I look at you, I don't understand

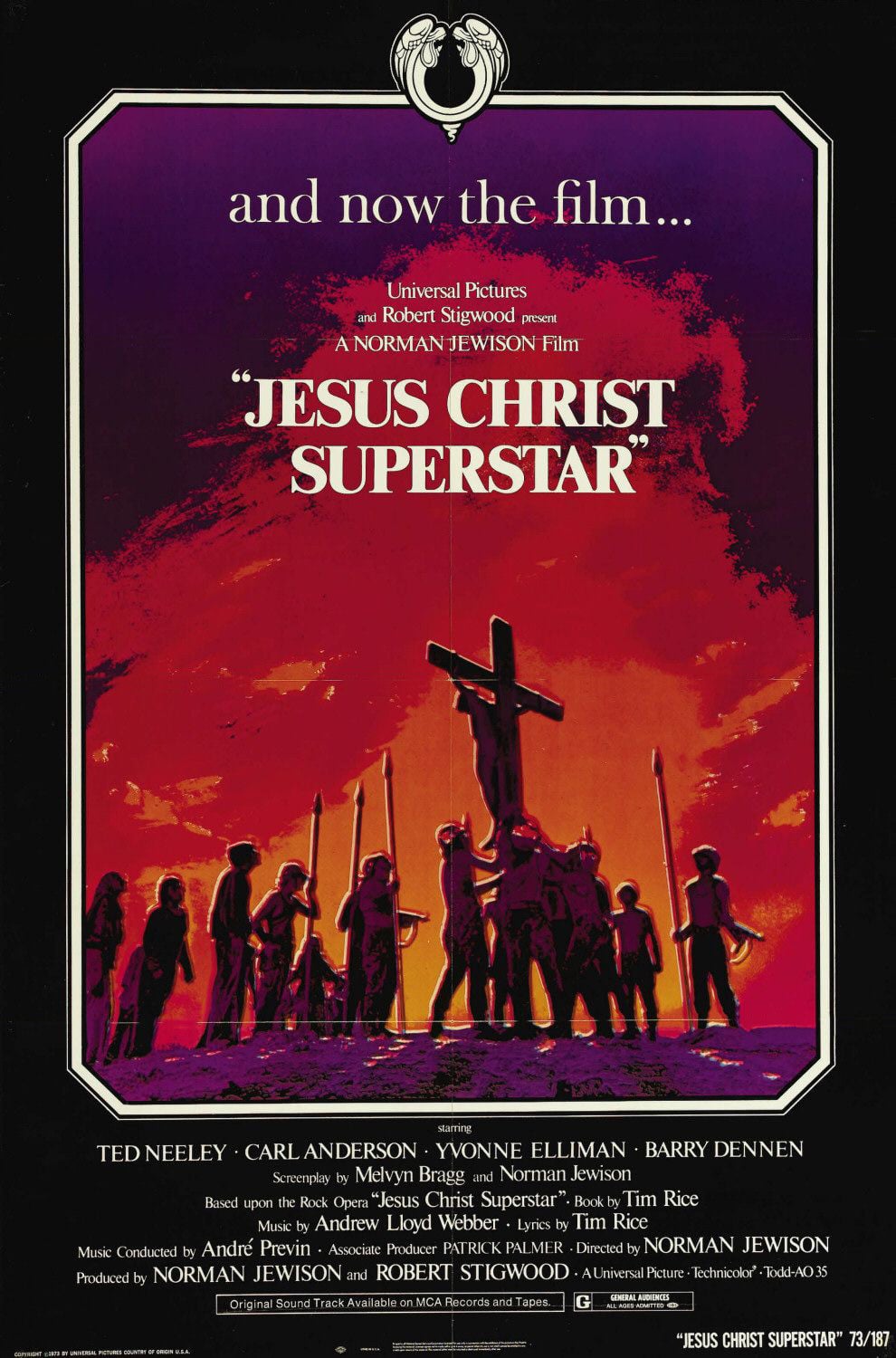

Inside every adult fan of musical theater is a teenage fan of musical theater, and like a lot of such teenagers, I had my Andrew Lloyd Webber phase. Which is why, even though the phrase "the best Andrew Lloyd Webber musical" feels to me now a little bit like saying "the funniest migraine I ever had", I must confess that I've thought about it. And what I've always thought is that the (sigh) best Andrew Lloyd Webber musical - probably the only one that actively rises all the way up to "actually good", for that matter - is the one that made his and lyricist Tim Rice's career: Jesus Christ Superstar, the two men's first full-length musical, born as a massively successful concept album in 1970, first put on stage in 1971, and adapted into a motion picture in 1973. And it is this third incarnation that we're here to discuss now, which is too bad: because as much as I still kind of dig the show as a show, the film is some absolutely beastly garbage - surely a candidate for the worst stage-to-screen musical adaptation ever, and this despite being the very next film directed by Norman Jewison after 1971's Fiddler on the Roof, which I'm on record declaring to be one of the best such adaptations.

There are a few reasons why Jesus Christ Superstar doesn't work as a movie, above and beyond the general truth that stage musicals and movie musicals are fundamentally different media, and to be fair, none of these can be attributed to incompetence. The thing is, it's a very 1973-ish movie, both in its aesthetics and it's idea of how human society works, and not in ways that remained timeless - for that matter, not in ways that weren't already a little bit kitschy by the time the film came out. Or, let me be blunt: zooms. There are many zooms in this film. One of the most famous (infamous?) things that happens in the movie comes almost all the way at the beginning, when the camera spots Judas Iscariot (Carl Anderson) sitting on a hilltop a couple of hundred yards away, and zooms towards him. As it arrives at him, it dissolves back to the starting point and zooms towards him again. It does this a total of four times, before finally dissolving to settle in near Judas in a long shot. I suppose the point is to ease us into Judas's POV, where we'll be spending the moody opening number "Heaven on Their Minds" listening to his concerns that his friend, the rabbi Jesus of Nazareth (Ted Neeley), is starting to become over-invested in the messianic overtones of his preaching. Like, all of those zooms are supposed to really just plunge us all the way into Judas's brain, or something. In practice, it's quite silly and feels like something an over-his-head student filmmaker might have thought would look cool until he actually saw it in practice. Or worse yet, he thought it worked.

Jesus Christ Superstar is full of Stupid Filmmaker Tricks like that: a crowd of zealous acolytes cross-dissolving in and out out an empty plaza, the ol' "two faces superimposed in the same frame" trick that, in Jewison's defense, wouldn't become the cheesiest possible way to stage a musical number until 1980s music videos ran it into the ground. Though even in 1973, it feels a bit hokey. But for all that I think the movie gets itself into all sorts of trouble from an excess of unthinking style, the bigger problem is fundamental. The way that Jewison and his co-adapter, Melvyn Bragg, went about adapting Lloyd Webber and Rice's story concept is just so fucking dumb, in a way that must have seemed ingenious when they came up with it, and given the film's still-vital fandom, I assume it seems ingenious to a lot of people who aren't me. But I hate it a lot.

I should probably start by clarifying what the show is, for those of you who don't know. Jesus Christ Superstar relates the last week in the life of Jesus, as laid out in the Synoptic Gospels, but the tone comes from a late-'60s humanist focus. This is very much a story of Jesus the man, told primarily through the eyes of Judas, who is growing increasingly disgusted with Jesus's willingness to accept the praise and adulation of his groupies, and Mary Magdalene (Yvonne Elliman), foremost of those groupies, who has fallen in love with Jesus the individual and is trying to cope with Jesus the celebrity. Some of the other apostles, as well as the local Jewish authorities led by the high priest Caiaphas (Bob Bingham) look on Jesus's movement as a primarily political one, advocating for radical change and upturning society. Only Jesus himself understands that his message is a simple one of love and respect for everybody. Every single word of this is communicated through classic rock or singer-songwriter ballads, with lyrics by Rice adopting an anachronistic, joshing tone that marries well with the usual derangement of his lyrics from this period ("Israel in 4 B.C. had no mass communication", "One thing I'll say for him, Jesus is cool", and "I don't need your blood money!"/"You might as well take it, we think that you should" are some personal favorites, though of course the most inane highlights are "Hosanna, hey-sanna, sanna sanna Ho-/sanna hey-sanna Hosanna" and "A jaded mandarin/A jaded mandarin/Like a jaded, faded, faded, jaded, jaded mandarin").

It's a very pointedly hippie-era story: specifically, a distinctly post-hippie story, or at least one that, at the time the show was written in 1969, fully expects the hippie movement to fail under the weight of personality cults, and too much radicalism swamping spirituality. And since this very much happened, kudos to Lloyd Webber and Rice for predicting it, even if it's probably less because they were astute and more because they were squares. The timeliness (it came out almost in the same moment as the other hippie religious musical, Godspell), and the radio-friendly music, made the concept album a huge bestseller and the stage production a monumental hit in the United Kingdom and only a somewhat smaller hit in the United States, all by the end of 1971. And this is significant, because in 1971, the hippie movement was dying, but in 1973, the hippie movement was dead, and one never quite feels with the movie, even less than one feels with the show, that the creators quite knew what the hell a hippie was.

This is even more of problem because the movie has way more hippies than the show did. For the show, after all, had only figurative hippies; the movie has only a figurative Jesus. One of the peculiarities of Jesus Christ Superstar is that there's no official staging instructions: it's basically just a song cycle that the director and other artists can do with as they will. And Jewison and company willed very hard. The film starts with a busload of hippie actors arriving in the Israel desert at the ruins of the ancient city of Avdat, where they put on a production of the musical to an audience of nobody. Or maybe an audience of filmmakers, I dunno. It's all very abstract: the Jewish council meets while standing on rebar scaffolding holding a part of the ruins together, Roman governor Pontius Pilate (Barry Dennen) holds court on a staircase leading t o nothing under the open blue sky. It's very easy to imagine this being a superb way to stage a live version of Jesus Christ Superstar, but in cinematic form, it feels very hollow and pointless, and the exhausting work that the cinematography and editing are doing to pretend that there's some level of formal artistry at play somehow makes it all seem shabbier. It's like nobody involved ever figured out how to actually stage musical numbers in a movie, so they just crossed their fingers and hoped that with enough dissolves and weird angles, it would seem okay.

For that is ultimately the worst sin of this movie, as it is the worst sin of any musical: the musical numbers are shit. They're performed well enough; Neeley's Jesus is a bit vocally scrawny compared to Ian Gillan on the concept album or Jeff Fenholt on the Broadway cast recording, but all of the other principles are at least very strong. But the staging is almost without exception garbage, either because Jewison is addicted to the forementioned zooms and dissolves, or because it looks ridiculous to see the angry Jewish priests, wearing costumes that look like they're cosplaying chess pieces at a leather bar, pounding for emphasis on a construction site. The film overrelies on close-ups to make Pilate seem more intense, giving Dennen (probably the strongest performance here otherwise) no room to interact with the rest of the cast. And I have no goddamn clue what's up with the comic number "King Herod's Song", sung terribly by Josh Mostel, and staged as a gruesome series of exaggerated poses and wild shifts in shot scale; it's like a child's imagined version of an orgy, on a barge left floating in three feet of lake water, while Neeley stands at the shoreline with absolutely no direction other than "don't react". And throughout the film, in the rare moments that there is significant choreography, it generally consists of a lot of jerky arm movements in straight lines, while the singers try their best to lip sync while performing what amounts to group calisthenics. The flat-footed staging ends up making the deliberate emptiness of the production seem even more bland and aimless, and for all my sneaking affection for this show, it's not remotely strong enough material to survive such a colossally hollow production.

There are a few reasons why Jesus Christ Superstar doesn't work as a movie, above and beyond the general truth that stage musicals and movie musicals are fundamentally different media, and to be fair, none of these can be attributed to incompetence. The thing is, it's a very 1973-ish movie, both in its aesthetics and it's idea of how human society works, and not in ways that remained timeless - for that matter, not in ways that weren't already a little bit kitschy by the time the film came out. Or, let me be blunt: zooms. There are many zooms in this film. One of the most famous (infamous?) things that happens in the movie comes almost all the way at the beginning, when the camera spots Judas Iscariot (Carl Anderson) sitting on a hilltop a couple of hundred yards away, and zooms towards him. As it arrives at him, it dissolves back to the starting point and zooms towards him again. It does this a total of four times, before finally dissolving to settle in near Judas in a long shot. I suppose the point is to ease us into Judas's POV, where we'll be spending the moody opening number "Heaven on Their Minds" listening to his concerns that his friend, the rabbi Jesus of Nazareth (Ted Neeley), is starting to become over-invested in the messianic overtones of his preaching. Like, all of those zooms are supposed to really just plunge us all the way into Judas's brain, or something. In practice, it's quite silly and feels like something an over-his-head student filmmaker might have thought would look cool until he actually saw it in practice. Or worse yet, he thought it worked.

Jesus Christ Superstar is full of Stupid Filmmaker Tricks like that: a crowd of zealous acolytes cross-dissolving in and out out an empty plaza, the ol' "two faces superimposed in the same frame" trick that, in Jewison's defense, wouldn't become the cheesiest possible way to stage a musical number until 1980s music videos ran it into the ground. Though even in 1973, it feels a bit hokey. But for all that I think the movie gets itself into all sorts of trouble from an excess of unthinking style, the bigger problem is fundamental. The way that Jewison and his co-adapter, Melvyn Bragg, went about adapting Lloyd Webber and Rice's story concept is just so fucking dumb, in a way that must have seemed ingenious when they came up with it, and given the film's still-vital fandom, I assume it seems ingenious to a lot of people who aren't me. But I hate it a lot.

I should probably start by clarifying what the show is, for those of you who don't know. Jesus Christ Superstar relates the last week in the life of Jesus, as laid out in the Synoptic Gospels, but the tone comes from a late-'60s humanist focus. This is very much a story of Jesus the man, told primarily through the eyes of Judas, who is growing increasingly disgusted with Jesus's willingness to accept the praise and adulation of his groupies, and Mary Magdalene (Yvonne Elliman), foremost of those groupies, who has fallen in love with Jesus the individual and is trying to cope with Jesus the celebrity. Some of the other apostles, as well as the local Jewish authorities led by the high priest Caiaphas (Bob Bingham) look on Jesus's movement as a primarily political one, advocating for radical change and upturning society. Only Jesus himself understands that his message is a simple one of love and respect for everybody. Every single word of this is communicated through classic rock or singer-songwriter ballads, with lyrics by Rice adopting an anachronistic, joshing tone that marries well with the usual derangement of his lyrics from this period ("Israel in 4 B.C. had no mass communication", "One thing I'll say for him, Jesus is cool", and "I don't need your blood money!"/"You might as well take it, we think that you should" are some personal favorites, though of course the most inane highlights are "Hosanna, hey-sanna, sanna sanna Ho-/sanna hey-sanna Hosanna" and "A jaded mandarin/A jaded mandarin/Like a jaded, faded, faded, jaded, jaded mandarin").

It's a very pointedly hippie-era story: specifically, a distinctly post-hippie story, or at least one that, at the time the show was written in 1969, fully expects the hippie movement to fail under the weight of personality cults, and too much radicalism swamping spirituality. And since this very much happened, kudos to Lloyd Webber and Rice for predicting it, even if it's probably less because they were astute and more because they were squares. The timeliness (it came out almost in the same moment as the other hippie religious musical, Godspell), and the radio-friendly music, made the concept album a huge bestseller and the stage production a monumental hit in the United Kingdom and only a somewhat smaller hit in the United States, all by the end of 1971. And this is significant, because in 1971, the hippie movement was dying, but in 1973, the hippie movement was dead, and one never quite feels with the movie, even less than one feels with the show, that the creators quite knew what the hell a hippie was.

This is even more of problem because the movie has way more hippies than the show did. For the show, after all, had only figurative hippies; the movie has only a figurative Jesus. One of the peculiarities of Jesus Christ Superstar is that there's no official staging instructions: it's basically just a song cycle that the director and other artists can do with as they will. And Jewison and company willed very hard. The film starts with a busload of hippie actors arriving in the Israel desert at the ruins of the ancient city of Avdat, where they put on a production of the musical to an audience of nobody. Or maybe an audience of filmmakers, I dunno. It's all very abstract: the Jewish council meets while standing on rebar scaffolding holding a part of the ruins together, Roman governor Pontius Pilate (Barry Dennen) holds court on a staircase leading t o nothing under the open blue sky. It's very easy to imagine this being a superb way to stage a live version of Jesus Christ Superstar, but in cinematic form, it feels very hollow and pointless, and the exhausting work that the cinematography and editing are doing to pretend that there's some level of formal artistry at play somehow makes it all seem shabbier. It's like nobody involved ever figured out how to actually stage musical numbers in a movie, so they just crossed their fingers and hoped that with enough dissolves and weird angles, it would seem okay.

For that is ultimately the worst sin of this movie, as it is the worst sin of any musical: the musical numbers are shit. They're performed well enough; Neeley's Jesus is a bit vocally scrawny compared to Ian Gillan on the concept album or Jeff Fenholt on the Broadway cast recording, but all of the other principles are at least very strong. But the staging is almost without exception garbage, either because Jewison is addicted to the forementioned zooms and dissolves, or because it looks ridiculous to see the angry Jewish priests, wearing costumes that look like they're cosplaying chess pieces at a leather bar, pounding for emphasis on a construction site. The film overrelies on close-ups to make Pilate seem more intense, giving Dennen (probably the strongest performance here otherwise) no room to interact with the rest of the cast. And I have no goddamn clue what's up with the comic number "King Herod's Song", sung terribly by Josh Mostel, and staged as a gruesome series of exaggerated poses and wild shifts in shot scale; it's like a child's imagined version of an orgy, on a barge left floating in three feet of lake water, while Neeley stands at the shoreline with absolutely no direction other than "don't react". And throughout the film, in the rare moments that there is significant choreography, it generally consists of a lot of jerky arm movements in straight lines, while the singers try their best to lip sync while performing what amounts to group calisthenics. The flat-footed staging ends up making the deliberate emptiness of the production seem even more bland and aimless, and for all my sneaking affection for this show, it's not remotely strong enough material to survive such a colossally hollow production.