Battle of Wills

One of those facts that keeps getting passed around about Gemini Man, to such a degree that I feel like a dull-witted asshole for bringing it up at all, is that the project (from a screenplay originally by Darren Lemke) was initially put into development at Disney in 1997. After being pushed at several of the most prominent male action stars of a certain age, it was abandoned for lack of sufficiently advanced technology, but its legend was kept alive long enough that in 2016, it could be sold to Skydance and put back into development, under the guiding hand of director Ang Lee and four producers, including '90s action maven Jerry Bruckheimer. The reason, I think, that this little anecdote has been so irresistible is that, in all honesty, it's pretty close to impossible to see what about this scenario has inspired people to keep the dream of making it alive for 20 years. I don't think I could go all the way to calling it "bad", but it's certainly not good; it's bland boilerplate, anybody who has seen more than two or three '90s action movies can probably predict the development of the plot in some detail, and the dialogue is cornier than August in Iowa. Just about the only thing in the screenplay as currently constituted (of the many people who laid hands on it over the years, David Benioff and Billy Ray are the two to receive onscreen credit alongside Lemke) has to recommend it is the hook, and it feels like you could get to the same hook in a lot of different ways.

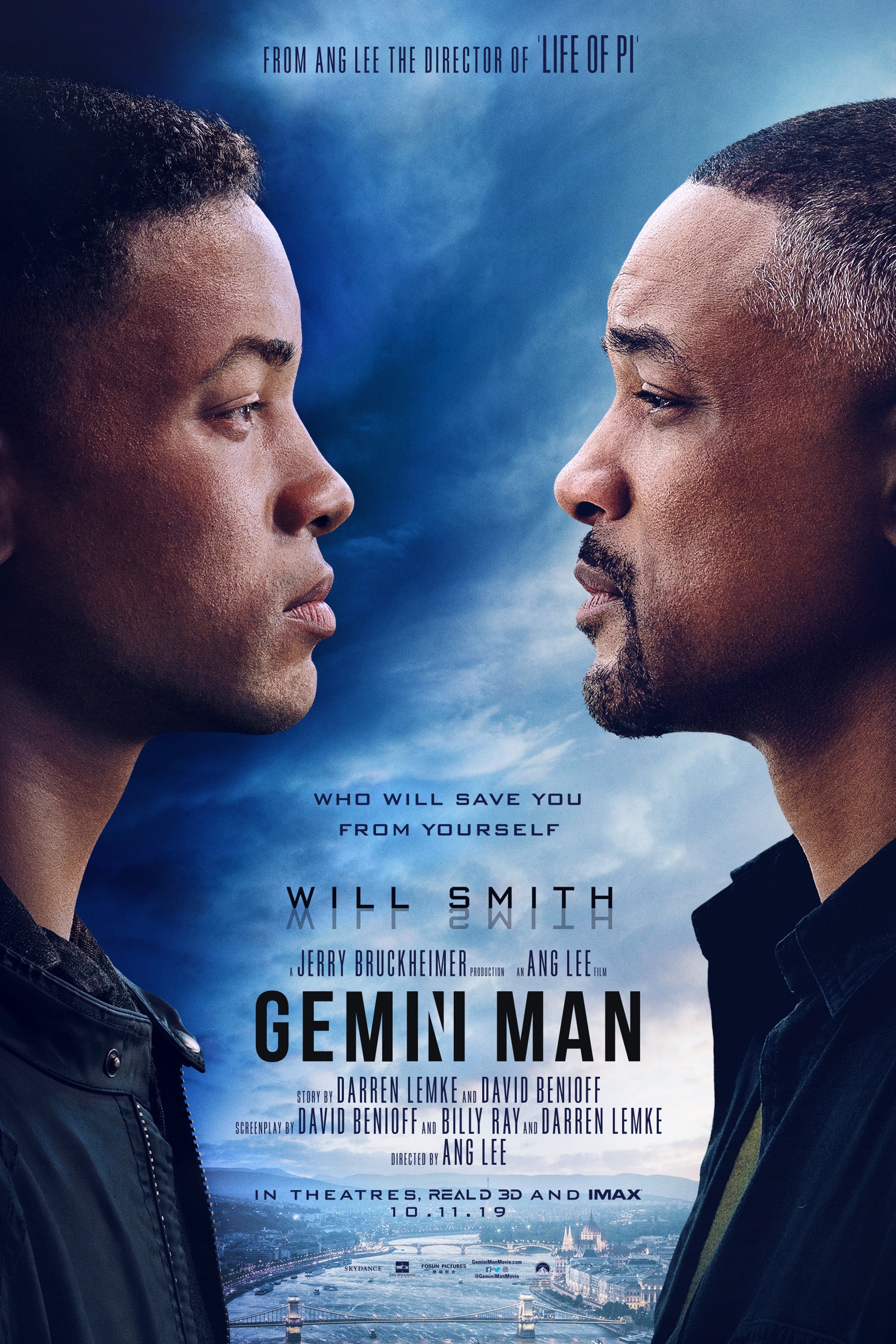

But it is, to be sure, a magnificent hook: take a movie star on the far side of fifty years old, known for his action roles, and pit him against his 25-years-younger clone, played by the same movie star in CGI. The star who got to sit down when the music stopped playing happens to have been Will Smith, who is on the one hand an absolutely perfect choice: his major stardom began when he was almost exactly the aged of his baby clone self, which gives the visual effects artist a convenient model; also, his star persona was solidified in the 1990s and in some ways feels like it ossified there, so he's a good fit to anchor an unabashed throwback to that era of popcorn filmmaking. Smith is also a sort of crummy fit, because he's aged well enough that it feels like a wig and some foundation would probably be enough to make him look 25 without any costly, less than 100% convincing CGI (though it's only actively terrible in the direct lighting of the film's last scene). But he's the fit we've got, anyway.

I hope you'll forgive me if I consider "boilerplate sci-fi action movie pits middle-aged assassin against himself but younger" to be sufficient for a plot recap, because the story of Gemini Man isn't by any remote sense its most engaging aspect. For that, we should instead turn to its action scenes, which are by and large very lovely, and more than worthy of the director of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, now working in a more self-consciously classicist mode. American cinema over the last several years has largely taken one of two different forms: CGI-poisoned setpieces chopped into small pieces in the editing room to hide the fact that the stars can't do action stunts, or big honking gonzo stunt spectaculars chopped into slightly less-small pieces to amp up the sense of impact. Gemini Man has one thing that I guess qualifies as a gonzo stunt that has presumably been sweetened with CGI - a flip kick performed by a gentleman who has left a motorcyle attached to the end of his leg - but almost all of the fights are pared-down and simple matters of people moving their fists, shooting quickly around corners, and dodging things that do not look like they could be dodged. And they do this in shots that are, by the standards of 2010s action cinema, kind of long. I mean, we're not talking European art cinema here. There's still a hell of a lot of cutting; it's just that there is not so much of the hell of a lot of cutting, and it's almost stately in a weird, wonderful way. The film is explicitly about the toll that time takes on the human body, and how science can augment human bodies; that its filming style would thus accentuate human bodies feels exactly right and comforting. This wouldn't matter if it wasn't also good action, of course, but it is. Small, and not very showy at all. But good, well-built, impressively tangible and (relatively) earthbound action.

Maybe we can thank Lee's sensibilities for this; it seems just as likely that the explanation lies in the film's status as a tech demo for the notorious high frame-rate 3-D cinema that hasn't gotten such a widespread showcase in the seven years since everybody despised it in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. I was certainly content to join in the condemnation back then; I am now happy and at least a little bit surprised to find myself singing the praises. To be sure, Gemini Man isn't The Hobbit; the 2012 film was projected at 48 frames per second, compared to 60 frames per second for the film, which doesn't seem like it should make a difference, but who knows, maybe it does. Maybe when Avatar 2: Avatars finally comes out several decades from now, James Cameron will figure out a way to boost that shit up to like 300 frames per second and it will the most beautiful thing we have ever seen. My better suspicion is that Gemini Man isn't a fantasy movie with wizards and elves and magical swords. It's a film that wants to feel grounded, wants us to feel the physical weight of Will Smith's 51-year-old body, and I mean, it does that. That's what high frame-rate does: it makes 3-D seem smoother and more present, makes the lighting brighter and the image crisper, makes everything feel more unpleasantly, persistently real. For me, that worked here; it worked in every single shot with water and doubly so for the shots under water (in fact, I can tell you the exact moment I became a convert: a shot below the water, looking up at two bodies falling into it, and the slowness of their floating movements and the extreme sense of too much realistic depth gave me an almost delirious awareness of the space). It very emphatically worked in every single action sequence; first-person motorcyle shots, and shots of explosions that feel bizarrely real, and bullets flying out of gatling guns like lasers. It's not immersive; far from it, it makes it feel sort of obvious that we're watching stuntmen and special effects. But it also makes the work of those stuntmen and those effects artists feel more dangerous and palpable and visceral than I'd have imagined possible. I got worked up watching the film, not from motion sickness like I expected, but from feeling like this was all too present, too much in my face, and that's an amazing feeling to get at a movie.

What the tech doesn't work for is dialogue scenes, and those are the majority of the film, but I got used to them pretty quickly. It maybe actually helps that the script is kind of cheesy, full of enormously solemn declarations of theme (Theme #1: Face your fears rather than let them control you. Theme #2: Dads suck), that Smith, Mary Elizabeth Winstead (as the plucky sidekick, who is pointedly kept from becoming his romantic interest), Benedict Wong (as the warm-hearted comic-relief buddy), and Clive Owen (as the militaristic villain, invested with a weird amount of recognisable humanity by the actor and director) intone with what I elect to believe is a knowing embrace of how strained the dialogue is. It's a hugely square movie, very on the nose, very grave, devoid of nuance; but the squareness feels oddly of a piece with how much Lee is willing to keep things small-ish. Anyway, the point being, it's all a bit cornball, and while I don't think the film is mocking itself, I also think it's inviting us to enjoy it as a form of earnest kitsch. So if it feels a little fake-ey due to the high frame-rate, well, it's not like one was going to ever fully emotionally invest in it. It's a matinee movie, meant to be dazzling and shiny and silly, and it basically is, all the ponderous gravity of its story and music and dialogue to the contrary. I kind of loved it a little bit; basic, solid, square action movies aren't common, and one that idly manages to serve as a commentary on Will Smith's movie star status and a quarter century of aging while providing its theme-park thrills is a rare treat indeed. It's such a gratifying movie, and one so entirely allergic to a modicum of cynicism, that I was happy to overlook how it's also not actually good.

But it is, to be sure, a magnificent hook: take a movie star on the far side of fifty years old, known for his action roles, and pit him against his 25-years-younger clone, played by the same movie star in CGI. The star who got to sit down when the music stopped playing happens to have been Will Smith, who is on the one hand an absolutely perfect choice: his major stardom began when he was almost exactly the aged of his baby clone self, which gives the visual effects artist a convenient model; also, his star persona was solidified in the 1990s and in some ways feels like it ossified there, so he's a good fit to anchor an unabashed throwback to that era of popcorn filmmaking. Smith is also a sort of crummy fit, because he's aged well enough that it feels like a wig and some foundation would probably be enough to make him look 25 without any costly, less than 100% convincing CGI (though it's only actively terrible in the direct lighting of the film's last scene). But he's the fit we've got, anyway.

I hope you'll forgive me if I consider "boilerplate sci-fi action movie pits middle-aged assassin against himself but younger" to be sufficient for a plot recap, because the story of Gemini Man isn't by any remote sense its most engaging aspect. For that, we should instead turn to its action scenes, which are by and large very lovely, and more than worthy of the director of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, now working in a more self-consciously classicist mode. American cinema over the last several years has largely taken one of two different forms: CGI-poisoned setpieces chopped into small pieces in the editing room to hide the fact that the stars can't do action stunts, or big honking gonzo stunt spectaculars chopped into slightly less-small pieces to amp up the sense of impact. Gemini Man has one thing that I guess qualifies as a gonzo stunt that has presumably been sweetened with CGI - a flip kick performed by a gentleman who has left a motorcyle attached to the end of his leg - but almost all of the fights are pared-down and simple matters of people moving their fists, shooting quickly around corners, and dodging things that do not look like they could be dodged. And they do this in shots that are, by the standards of 2010s action cinema, kind of long. I mean, we're not talking European art cinema here. There's still a hell of a lot of cutting; it's just that there is not so much of the hell of a lot of cutting, and it's almost stately in a weird, wonderful way. The film is explicitly about the toll that time takes on the human body, and how science can augment human bodies; that its filming style would thus accentuate human bodies feels exactly right and comforting. This wouldn't matter if it wasn't also good action, of course, but it is. Small, and not very showy at all. But good, well-built, impressively tangible and (relatively) earthbound action.

Maybe we can thank Lee's sensibilities for this; it seems just as likely that the explanation lies in the film's status as a tech demo for the notorious high frame-rate 3-D cinema that hasn't gotten such a widespread showcase in the seven years since everybody despised it in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. I was certainly content to join in the condemnation back then; I am now happy and at least a little bit surprised to find myself singing the praises. To be sure, Gemini Man isn't The Hobbit; the 2012 film was projected at 48 frames per second, compared to 60 frames per second for the film, which doesn't seem like it should make a difference, but who knows, maybe it does. Maybe when Avatar 2: Avatars finally comes out several decades from now, James Cameron will figure out a way to boost that shit up to like 300 frames per second and it will the most beautiful thing we have ever seen. My better suspicion is that Gemini Man isn't a fantasy movie with wizards and elves and magical swords. It's a film that wants to feel grounded, wants us to feel the physical weight of Will Smith's 51-year-old body, and I mean, it does that. That's what high frame-rate does: it makes 3-D seem smoother and more present, makes the lighting brighter and the image crisper, makes everything feel more unpleasantly, persistently real. For me, that worked here; it worked in every single shot with water and doubly so for the shots under water (in fact, I can tell you the exact moment I became a convert: a shot below the water, looking up at two bodies falling into it, and the slowness of their floating movements and the extreme sense of too much realistic depth gave me an almost delirious awareness of the space). It very emphatically worked in every single action sequence; first-person motorcyle shots, and shots of explosions that feel bizarrely real, and bullets flying out of gatling guns like lasers. It's not immersive; far from it, it makes it feel sort of obvious that we're watching stuntmen and special effects. But it also makes the work of those stuntmen and those effects artists feel more dangerous and palpable and visceral than I'd have imagined possible. I got worked up watching the film, not from motion sickness like I expected, but from feeling like this was all too present, too much in my face, and that's an amazing feeling to get at a movie.

What the tech doesn't work for is dialogue scenes, and those are the majority of the film, but I got used to them pretty quickly. It maybe actually helps that the script is kind of cheesy, full of enormously solemn declarations of theme (Theme #1: Face your fears rather than let them control you. Theme #2: Dads suck), that Smith, Mary Elizabeth Winstead (as the plucky sidekick, who is pointedly kept from becoming his romantic interest), Benedict Wong (as the warm-hearted comic-relief buddy), and Clive Owen (as the militaristic villain, invested with a weird amount of recognisable humanity by the actor and director) intone with what I elect to believe is a knowing embrace of how strained the dialogue is. It's a hugely square movie, very on the nose, very grave, devoid of nuance; but the squareness feels oddly of a piece with how much Lee is willing to keep things small-ish. Anyway, the point being, it's all a bit cornball, and while I don't think the film is mocking itself, I also think it's inviting us to enjoy it as a form of earnest kitsch. So if it feels a little fake-ey due to the high frame-rate, well, it's not like one was going to ever fully emotionally invest in it. It's a matinee movie, meant to be dazzling and shiny and silly, and it basically is, all the ponderous gravity of its story and music and dialogue to the contrary. I kind of loved it a little bit; basic, solid, square action movies aren't common, and one that idly manages to serve as a commentary on Will Smith's movie star status and a quarter century of aging while providing its theme-park thrills is a rare treat indeed. It's such a gratifying movie, and one so entirely allergic to a modicum of cynicism, that I was happy to overlook how it's also not actually good.

Categories: action, popcorn movies, science fiction, the third dimension