Summer of Blood: Sci-Fi Horror - In goo we trust

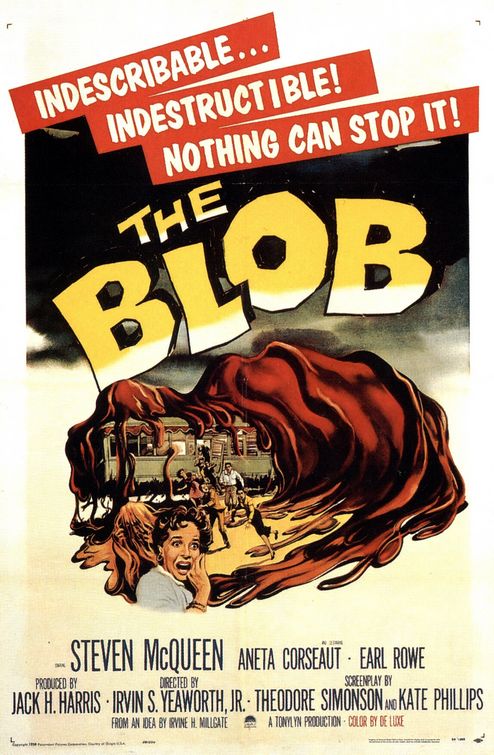

There is very little about 1958's The Blob, on paper, that distinguishes it from all the other God knows how many dozens of films from that decade that pitch a bunch of small-town teenagers against some kind of monster from outer space, a mad scientist's lab, or maybe just a good old-fashioned nuclear disaster. It was in color at at time when that was still novel for a genre film of limited budget, but that wasn't distinctive enough for distributor Paramount (it was an independent film produced by newbie Jack H. Harris), who stuck it as the B-side of a double-feature, following their in-house I Married a Monster from Outer Space. It's cheap as all hell, the story is paint-by-numbers in every way except its vagueness about what its titular monster is all about, and the 28-year-old lead actor is hilariously unconvincing as a high school student. Or, frankly as a 28-year-old. And the rest of the cast is exactly like any other set of generic nobodies plucked from a casting agent's second-string binder.

All that being true, some one-of-a-kind alchemy was going on, because The Blob is anything but generic. Of all the movies made on this basic model at that time, I'm not sure that there's another one to have risen so far above the crowd in popular esteem, which it did almost immediately: it was so much more popular than I Married a Monster that Paramount was obliged to swap the two films and focus their marketing on The Blob. In later years, the film became one of the handful of genre films from its era to receive a remake, in 1988; it enjoys the even rarer distinction, for B-picture, of securing a spot in the Criterion Collection. The ingredients might be almost exactly the same as so many long-forgotten drive-in programmers, but the completed dish is incredibly special, one of the most personable sci-fi horror films of its generation, though I am not entirely sure I would necessarily run right along into calling it, therefore, one of the best.

The two most obvious pillars of the film's success are its rather unconventional monster, and that weathered 28-year-old playing the good bad boy hero Steve Andrews. Because that actor, in just his second appearance in a feature, was none other than Steve McQueen, future embodiment of all things cool and manly in the 1960s, in his starmaking role. Now, I would not be so brazen as to suggest that what McQueen is up to in the film counts as great acting, or even notably good acting; there's really not much in the script by Theodore Simonson and Kate Phillips (the pen name of retired actor Kay Linaker) that would enable an actor to rise to particularly impressive heights, and it would take somebody with more experience than McQueen had to outthink writing like this. What he had, though, in naturally-occurring quantities that very few movie stars throughout history could compete with, was effortless charisma and innate screen presence. Seeing that talent turned towards of loners and thieves and other assorted tough guys is pretty much standard-issue Charming Rogue stuff; there's something much more bracing (and I imagine it was more bracing yet in '58, when nobody knew who the hell McQueen was) about watching that funneled into a teenager. For American teenagers are, by their nature, the most swaggering and image-obsessed figures in God's creation, and even as McQueen is almost hilariously incapable of looking the part, he has the flinty, antagonistic attitude down cold. Steve Andrews is, and I say this in all due awareness of the dangers of hyperbole, the most interesting teen male in a horror film of the '50s or '60s: there's a sharpness to him not found in other hero types, and a moral backbone rare in the hoods and greasers (who are found in this movie, and treated with unusual sympathy).

The relative uniqueness of Steve among his cinematic peers points out one of the subtler points that might help explain The Blob's impact: this is a film that treats its teen characters with unusual respect and dignity. This was, lest we forget, during the first generation of teenagers as the driving force in mass culture (which, as I take it, is an exclusively post-WWII phenomenon), and teens as movie protagonists - and villains, and the whole entire casts of movies - had become fairly common, but you'd have to look a long time for a movie prior to this that so fully stands behind its teen characters, from the conventionally good Steve and his girlfriend Jane Martin (Aneta Corsaut) to the punks off doing punk things like sullenly watch very daft-looking experimental horror film at the midnight show (you'd swear that it had to be a parody, it looks so incomprehensible, but it actually exists: it's a 1955 film called Dementia), in opposition to the adults who disregard, misunderstand, or openly hate them and dismiss their warnings of a mysterious terrible blob-thing from space digesting humans whole. Though for all that The Blob puts forth, with some passion, the idea that adults need to trust the kids more, because even the naughtiest teens are still basically decent, the film's efforts to provide plausible reasons for giving everyone reason to disbelieve Steve and Jane are quite thorough, right up to the point that the blob gives up hiding and eats its way through a movie theater. It helps the film as horror: the inability to budge the authorities to do anything starts to take on the logic of nightmare. And it helps it as drama: it feeds Steve and Jane's frustration and gives them more weight as characters. Which is an insane thing to say about a drive-in movie, but there it is. It is, of course, not a character piece as such, particularly in moments such as when one character's whole family turns out to be dead, and by the end of the scene, he's apparently forgotten, in his and the film's anxiety to make sure that a dog made it out okay. But for junk food, this one has unusual interest in making its characters plausible people whom we like because of their actions and intelligence, not just because it's a movie and they've been plugged in as our identification points.

But I have drifted, without mentioning the film's other great triumph: the blob. It's utterly primitive, just silcone gel with red dye being shaken from offscreen, being squeezed through holes, and such. It's also one of the great original movie monsters of an era, for it is one of the most totally alien of alien beings. Hell, the fact that it's so clearly a prop adds to its effectiveness: while it oozes towards its victims and across models with what has to be malevolent intent, the eye and brain refuse to process it as a living thing at all. It can't be resolved into anything explicable, either visually or in the writing, so it comes off as a destructive force that can't be understood or predicted in any way, and thus cannot be fought. And, just as an added bonus, it turns a darker shade of red throughout the movie, a subtle and incredibly gross touch.

In a lot of ways, The Blob is all the usual junk: it openly wears its threadbare budget in its conspicuous sleight-of-hand editing, and one of the most transparently fake car rigs I have ever seen in a movie. The characters are undeniably written with more sympathy and thoughtfulness than the usual teen pandering crap, but the cast, beyond McQueen and Earl Rowe as the main cop, simply don't have the chops to make any kind of remote impression (that being said, nobody is bad, and that's an achievement in this kind of film). But it's junk with conviction, as director Irvin Yeaworth (a veteran of Christian devotional shorts) refuses to play up ridiculousness promised by the jaunty Burt Bachrach/Mack David theme song and inherent to the scenario. He runs the film like a jungle cat, slinking along and pouncing, and while the scale of the production isn't conducive to much in the way of creative imagery, it says a lot that Yeaworth always shoots the blob, even in its smallest form, from angles that make it seem imposing and distressing. That's the film in a nutshell: it takes itself its characters, and its monster very seriously. There are holes in the script and holes in the production, and it really doesn't have much subtext beyond "I feel ya, kids, grown-ups are the worst" (you could squeeze some Cold War "devoured by the conformist blob" rhetoric out of there, but what '50s horror film didn't have anti-Soviet undertones?), all of which make it hard to support calling it one of the all-time great sci-fi horror films, as is frequently done. But it's a genre essential, and infinitely more rewarding in every regard than it has the slightest reason to be.

Body Count: Unclear. Even the cops whose job it is, theoretically, to know this, can't do better than estimating in the 40s or 50s. There are around a half-dozen "featured" deaths.

All that being true, some one-of-a-kind alchemy was going on, because The Blob is anything but generic. Of all the movies made on this basic model at that time, I'm not sure that there's another one to have risen so far above the crowd in popular esteem, which it did almost immediately: it was so much more popular than I Married a Monster that Paramount was obliged to swap the two films and focus their marketing on The Blob. In later years, the film became one of the handful of genre films from its era to receive a remake, in 1988; it enjoys the even rarer distinction, for B-picture, of securing a spot in the Criterion Collection. The ingredients might be almost exactly the same as so many long-forgotten drive-in programmers, but the completed dish is incredibly special, one of the most personable sci-fi horror films of its generation, though I am not entirely sure I would necessarily run right along into calling it, therefore, one of the best.

The two most obvious pillars of the film's success are its rather unconventional monster, and that weathered 28-year-old playing the good bad boy hero Steve Andrews. Because that actor, in just his second appearance in a feature, was none other than Steve McQueen, future embodiment of all things cool and manly in the 1960s, in his starmaking role. Now, I would not be so brazen as to suggest that what McQueen is up to in the film counts as great acting, or even notably good acting; there's really not much in the script by Theodore Simonson and Kate Phillips (the pen name of retired actor Kay Linaker) that would enable an actor to rise to particularly impressive heights, and it would take somebody with more experience than McQueen had to outthink writing like this. What he had, though, in naturally-occurring quantities that very few movie stars throughout history could compete with, was effortless charisma and innate screen presence. Seeing that talent turned towards of loners and thieves and other assorted tough guys is pretty much standard-issue Charming Rogue stuff; there's something much more bracing (and I imagine it was more bracing yet in '58, when nobody knew who the hell McQueen was) about watching that funneled into a teenager. For American teenagers are, by their nature, the most swaggering and image-obsessed figures in God's creation, and even as McQueen is almost hilariously incapable of looking the part, he has the flinty, antagonistic attitude down cold. Steve Andrews is, and I say this in all due awareness of the dangers of hyperbole, the most interesting teen male in a horror film of the '50s or '60s: there's a sharpness to him not found in other hero types, and a moral backbone rare in the hoods and greasers (who are found in this movie, and treated with unusual sympathy).

The relative uniqueness of Steve among his cinematic peers points out one of the subtler points that might help explain The Blob's impact: this is a film that treats its teen characters with unusual respect and dignity. This was, lest we forget, during the first generation of teenagers as the driving force in mass culture (which, as I take it, is an exclusively post-WWII phenomenon), and teens as movie protagonists - and villains, and the whole entire casts of movies - had become fairly common, but you'd have to look a long time for a movie prior to this that so fully stands behind its teen characters, from the conventionally good Steve and his girlfriend Jane Martin (Aneta Corsaut) to the punks off doing punk things like sullenly watch very daft-looking experimental horror film at the midnight show (you'd swear that it had to be a parody, it looks so incomprehensible, but it actually exists: it's a 1955 film called Dementia), in opposition to the adults who disregard, misunderstand, or openly hate them and dismiss their warnings of a mysterious terrible blob-thing from space digesting humans whole. Though for all that The Blob puts forth, with some passion, the idea that adults need to trust the kids more, because even the naughtiest teens are still basically decent, the film's efforts to provide plausible reasons for giving everyone reason to disbelieve Steve and Jane are quite thorough, right up to the point that the blob gives up hiding and eats its way through a movie theater. It helps the film as horror: the inability to budge the authorities to do anything starts to take on the logic of nightmare. And it helps it as drama: it feeds Steve and Jane's frustration and gives them more weight as characters. Which is an insane thing to say about a drive-in movie, but there it is. It is, of course, not a character piece as such, particularly in moments such as when one character's whole family turns out to be dead, and by the end of the scene, he's apparently forgotten, in his and the film's anxiety to make sure that a dog made it out okay. But for junk food, this one has unusual interest in making its characters plausible people whom we like because of their actions and intelligence, not just because it's a movie and they've been plugged in as our identification points.

But I have drifted, without mentioning the film's other great triumph: the blob. It's utterly primitive, just silcone gel with red dye being shaken from offscreen, being squeezed through holes, and such. It's also one of the great original movie monsters of an era, for it is one of the most totally alien of alien beings. Hell, the fact that it's so clearly a prop adds to its effectiveness: while it oozes towards its victims and across models with what has to be malevolent intent, the eye and brain refuse to process it as a living thing at all. It can't be resolved into anything explicable, either visually or in the writing, so it comes off as a destructive force that can't be understood or predicted in any way, and thus cannot be fought. And, just as an added bonus, it turns a darker shade of red throughout the movie, a subtle and incredibly gross touch.

In a lot of ways, The Blob is all the usual junk: it openly wears its threadbare budget in its conspicuous sleight-of-hand editing, and one of the most transparently fake car rigs I have ever seen in a movie. The characters are undeniably written with more sympathy and thoughtfulness than the usual teen pandering crap, but the cast, beyond McQueen and Earl Rowe as the main cop, simply don't have the chops to make any kind of remote impression (that being said, nobody is bad, and that's an achievement in this kind of film). But it's junk with conviction, as director Irvin Yeaworth (a veteran of Christian devotional shorts) refuses to play up ridiculousness promised by the jaunty Burt Bachrach/Mack David theme song and inherent to the scenario. He runs the film like a jungle cat, slinking along and pouncing, and while the scale of the production isn't conducive to much in the way of creative imagery, it says a lot that Yeaworth always shoots the blob, even in its smallest form, from angles that make it seem imposing and distressing. That's the film in a nutshell: it takes itself its characters, and its monster very seriously. There are holes in the script and holes in the production, and it really doesn't have much subtext beyond "I feel ya, kids, grown-ups are the worst" (you could squeeze some Cold War "devoured by the conformist blob" rhetoric out of there, but what '50s horror film didn't have anti-Soviet undertones?), all of which make it hard to support calling it one of the all-time great sci-fi horror films, as is frequently done. But it's a genre essential, and infinitely more rewarding in every regard than it has the slightest reason to be.

Body Count: Unclear. Even the cops whose job it is, theoretically, to know this, can't do better than estimating in the 40s or 50s. There are around a half-dozen "featured" deaths.

Categories: horror, science fiction, summer of blood, teen movies, thrillers