Blockbuster History: Killer dolls

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the history of horror stories about dolls, puppets, and other human-shaped objects that have been taken over by some evil force and made murderous - a history in which Annabelle: Creation is the newest entry - is old, older than cinema as a medium. But it's with cinema that we'll remain concerned for the moment.

It would take a bigger sociopathic monster than I to declare that the 1987 film Dolls is a "kids' movie", in the strict sense that it is a film which parents should watch with their kids. It's a violent horror film, after all, with dialogue that could trigger the "what's a 'threesome'?" conversation earlier than the parent might prefer.

But in a much looser sense, aye, this is sort of exactly what I think of when I think of kids' movies. It is a film that earnestly - even innocently! - attempts to deal with the world as a child sees it, in service to telling an exceptionally pure fairy tale story, replete with fairy godmothers, witchcraft, and a suitably grim ending for the people we hate, which is deeply satisfying on a moral level even when adult good sense is screaming in silent horror that this is just horrible how things wrapped up. And it's gory in just exactly the sense that sounds repulsive and terrifying but not actually disturbing, more florid than visceral, and perhaps I was just a morbid kid running with other morbid kids, but I seem to remember descriptions of things like we see in Dolls causing more of a pleasurable shiver than a sleepless night. It is a kids' movie in that it remembers the mental state of being a kid, and respects it with deep sincerity.

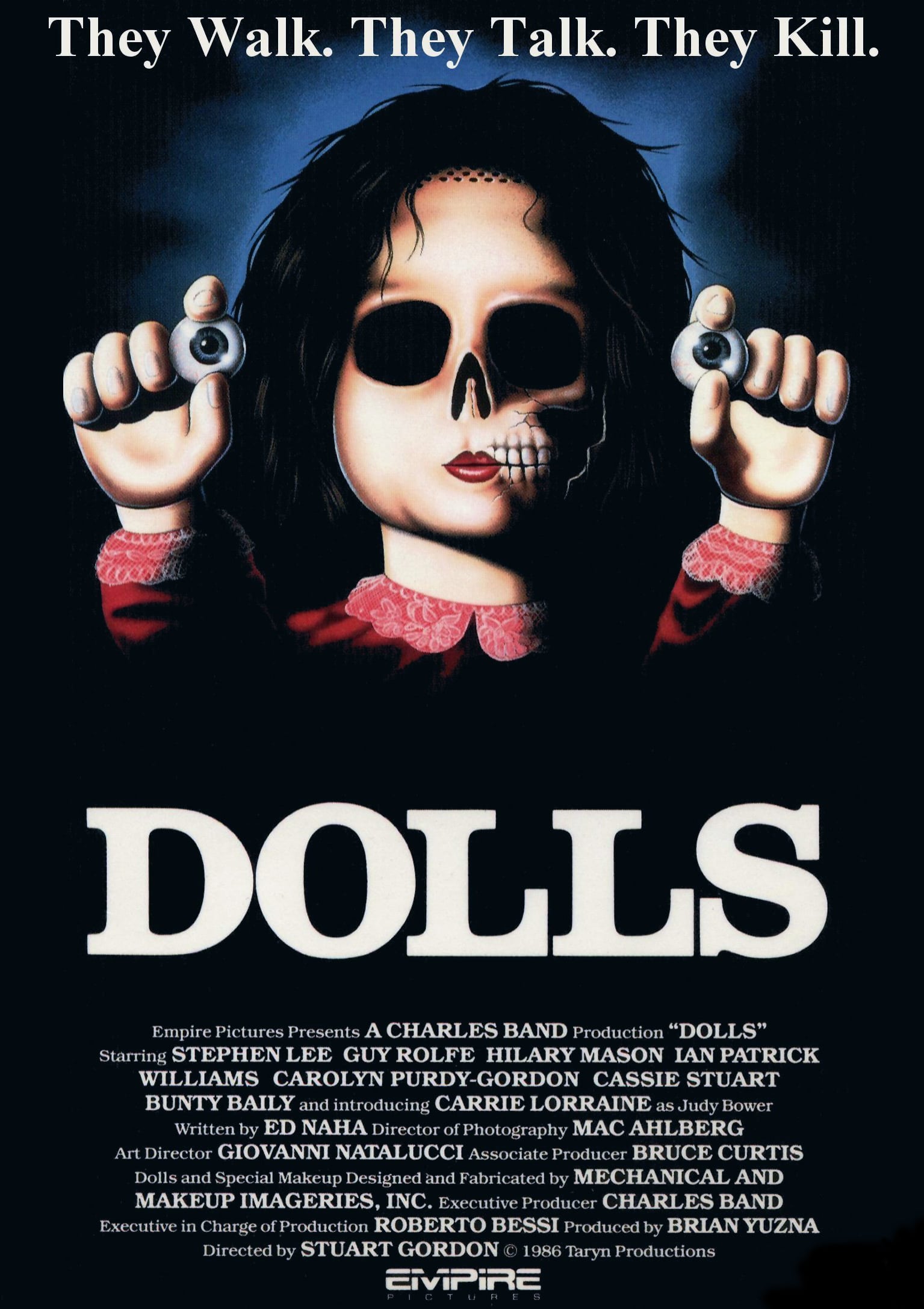

Not at all bad for the third feature directed by Stuart Gordon, who'd made two deeply, delightfully fucked-up H.P. Lovecraft adaptations before this (1985's classic Re-Animator and 1986's oughta-be-a-classic From Beyond). Even better for something that came out of executive producer Charles Band's Empire Pictures; for if ever there was a film producer more reliably committed to the schlockiest horror and action films than Charles Band, and with anything even slightly close to Band's unbelievably prolific output, I can't name him. And Dolls falls squarely in to the Bandiest of Band obsessions: films about killer toys are weirdly prominent in his filmography, typified by Puppet Master and its sequels. For it to have simply managed the feat of not sucking was already a triumph; that it's actually pretty good is the stuff of miracles.

The screenplay by Ed Naha (who'd work again with Gordon and Dolls producer Brian Yuzna on writing the story for Disney's Honey, I Shrunk the Kids) is something of an Agatha Christie type deal: one stormy night, six travelers find themselves stranded in a rambling English manor, hosted by two cheery old people, so full of smiles and goodwill that it's impossible to not instantly suspect them of something. The old couple are Gabriel (Guy Rolfe) and Hilary Hartwicke (Hilary Mason), collectors and creators of old-fashioned, hand-crafted dolls, which line seemingly every shelf in the sprawling old place. The stranded travelers come in two sets of three: first we have the Bowers, a very unhappy American family made up of little Judy (Carrie Lorraine), some eight years old, her distant and unloving father David (Ian Patrick Williams), and her outwardly mean, violent stepmother Rosemary (Carolyn Purdy-Gordon, a mainstay of Stuart Gordon's films - as she well might be, they're married). A wicked stepmother, you could go so far as to say, and I do believe that Dolls wants us to do that. The other trio is doughy, nervous, distinctly childlike Ralph (Stephen Lee), also an American, and the hitchhiking punk fanciers he's picked up, Isabel (Bunty Bailey) and Enid (Cassie Stuart).

It's certainly not giving away the game to say that the Hartwickes' dolls turn out to be living beings of some sort, and during the very long, unpleasant night of the storm, they go on the attack against every one of the five adult travelers. Judy is saved by her very ebullient enthusiasm for a Punch doll that Gabriel gives her (this is, FYI, the kind of movie that prefers to spell out the "Punch and Judy" connection than allow us to stumble into on our own), and more generally by having an openness to the magic and mystery of the dolls, without any of the adults' cynicism and meanness. And this is very unmistakably the whole message of Dolls, which celebrates the guilelessness of childhood play by making the grown-ups who belittle Judy's intelligence suffer greatly.

As far as that all goes, it's at least a slightly terrific movie. Gordon's directing treats this material with the utmost gravity, and the film's horror is always keyed to Judy. One of the most strikingly creepy images, repeated at least a couple of times, is entirely about the feeling of being a child in an adult world, with the camera high above Judy as she stands next to somebody much taller, exaggerating Lorraine's smallness within the frame and making her seem quite overwhelmed by everything around her. And as I've suggested, the things that happen are scary in the manner of a bunch of children - especially morbid children, perhaps - trying to freak each other out at a sleepover. "And then her eyes fell out!" "And then he saw blood on her slippers!" That kind of thing.

Truth be told, Dolls actually does manage to be pretty damn creepy, often enough. It's mostly because of the dolls themselves, shockingly expressive little buggers designed by John Brunner with a bit more flexibility in their eyes and mouths than your brain is quite willing to allow as a possibility. And the way that Gordon frames them, with help from cinematographer Mac Ahlberg (who quite gamely lights and frames for doll-scale close-ups, such that you start to forget they're props, not characters), and the way that editor Lee Percy pieces together the doll reaction shots, contribute to the altogether inescapable feeling that the little things are actually thinking, plotting, and nurturing their hate for those who disrespect the joy of childhood.

But even some of the non-doll moments work extremely well; early on, the first flush of Judy's imagination, as well as the first symptom of how broken and awful her family life is, comes in the form of a fantasy about a giant teddy bear ripping her father and stepmother apart. And you know what, seeing a person in a human-sized teddy bear costume emerging from the mist is just way the hell more uncanny and unnerving than seeing a blood-covered maniac with a knife, because of the sheer incongruity. The whole "nobody likes a clown at midnight" thing.

So in the face of all that, why can't I convince myself that Dolls is at least a moderate classic of fabulistic horror? Simple: it's too damn cheap. Or rather, it's cheap in debilitating ways - those dolls are magnificent creations, at least, and would be worthy in a much more prestigious production than this.

But the place where the cash shortage presents itself more obviously just hurt, so bad. One of these is the score, by Fuzzbee Morse, which is all the worst things about chintzy Casio keyboard synthetic music from low-budget and DTV horror in the '80s, despite an initially promising main theme (the credits, between the chiaroscuro lighting on disembodied doll heads, and Morse's ominously dreamy noodling, are full of a promise of atmosphere that the movie generally makes good on - but the music is all downhill from here). It's not worse than dozens or hundreds of other scores, but given how good Dolls is at rising above its Empire Pictures-level origins in so many ways, the constant aural reminder that nope, this is just a crummy no-budget indie horror joint is galling.

The other big problem is the cast. It's a weird shortcoming for the Gordon-Yuzna pairing, who had used no-name actors with extravagantly great results in both Re-Animator and From Beyond. But outside of the twinkle-eyed old folks playing a sweetness that disorientingly cuts against their role as menacing villains, and are both quite good (though I am maybe being generous to Mason with that "quite"), the cast is nothing but flat notes. Purdy-Gordon comes the closest to doing something with her role, though the necessary shortcomings of the "ice-cold rich bitch who'd as happily see her stepdaughter eaten by wolverines as not" figure mean that she can only go so far. And Lorraine is good more often than not, and I think it's probably more the direction than her that leads to her very bad scenes when she's overplaying the "I am an innocent child, pure of heart, with faith in the magical things in this world" card. The other four are all varying degrees of terrible: Lee overplays the same card that Lorraine does, and it's much less charming in an adult than a child, and there's nothing at all redeeming about Williams's one-note asshole nastiness, or Bailey and Stuart's arms race to see who can out-slattern the other.

The almost total lack of compelling human figures hobbles Dolls considerably, but it's not a killing blow: nuance-free shithead grown-ups fit the theme well enough that a more generous viewer than I might even regard it as a deliberate choice. Still, the flatness of everybody who isn't a potentially insane dollmaking warlock leaves the film with a hole where it's heart should be. And this is a very heart-driven horror movie, all things considered. I can only imagine liking it more on subsequent viewings - what works, works damn well, and what doesn't is a flaw common to literally tens of dozens of similar low-budget horror pictures, making it easier to overlook. Still, it's the first Stuart Gordon-Brian Yuzna film that isn't a home run, and easy to be a little more bitter at it for that reason, particularly given that Gordon and Yuzna, together and separately, never regained the mojo that they lost with this picture.

It would take a bigger sociopathic monster than I to declare that the 1987 film Dolls is a "kids' movie", in the strict sense that it is a film which parents should watch with their kids. It's a violent horror film, after all, with dialogue that could trigger the "what's a 'threesome'?" conversation earlier than the parent might prefer.

But in a much looser sense, aye, this is sort of exactly what I think of when I think of kids' movies. It is a film that earnestly - even innocently! - attempts to deal with the world as a child sees it, in service to telling an exceptionally pure fairy tale story, replete with fairy godmothers, witchcraft, and a suitably grim ending for the people we hate, which is deeply satisfying on a moral level even when adult good sense is screaming in silent horror that this is just horrible how things wrapped up. And it's gory in just exactly the sense that sounds repulsive and terrifying but not actually disturbing, more florid than visceral, and perhaps I was just a morbid kid running with other morbid kids, but I seem to remember descriptions of things like we see in Dolls causing more of a pleasurable shiver than a sleepless night. It is a kids' movie in that it remembers the mental state of being a kid, and respects it with deep sincerity.

Not at all bad for the third feature directed by Stuart Gordon, who'd made two deeply, delightfully fucked-up H.P. Lovecraft adaptations before this (1985's classic Re-Animator and 1986's oughta-be-a-classic From Beyond). Even better for something that came out of executive producer Charles Band's Empire Pictures; for if ever there was a film producer more reliably committed to the schlockiest horror and action films than Charles Band, and with anything even slightly close to Band's unbelievably prolific output, I can't name him. And Dolls falls squarely in to the Bandiest of Band obsessions: films about killer toys are weirdly prominent in his filmography, typified by Puppet Master and its sequels. For it to have simply managed the feat of not sucking was already a triumph; that it's actually pretty good is the stuff of miracles.

The screenplay by Ed Naha (who'd work again with Gordon and Dolls producer Brian Yuzna on writing the story for Disney's Honey, I Shrunk the Kids) is something of an Agatha Christie type deal: one stormy night, six travelers find themselves stranded in a rambling English manor, hosted by two cheery old people, so full of smiles and goodwill that it's impossible to not instantly suspect them of something. The old couple are Gabriel (Guy Rolfe) and Hilary Hartwicke (Hilary Mason), collectors and creators of old-fashioned, hand-crafted dolls, which line seemingly every shelf in the sprawling old place. The stranded travelers come in two sets of three: first we have the Bowers, a very unhappy American family made up of little Judy (Carrie Lorraine), some eight years old, her distant and unloving father David (Ian Patrick Williams), and her outwardly mean, violent stepmother Rosemary (Carolyn Purdy-Gordon, a mainstay of Stuart Gordon's films - as she well might be, they're married). A wicked stepmother, you could go so far as to say, and I do believe that Dolls wants us to do that. The other trio is doughy, nervous, distinctly childlike Ralph (Stephen Lee), also an American, and the hitchhiking punk fanciers he's picked up, Isabel (Bunty Bailey) and Enid (Cassie Stuart).

It's certainly not giving away the game to say that the Hartwickes' dolls turn out to be living beings of some sort, and during the very long, unpleasant night of the storm, they go on the attack against every one of the five adult travelers. Judy is saved by her very ebullient enthusiasm for a Punch doll that Gabriel gives her (this is, FYI, the kind of movie that prefers to spell out the "Punch and Judy" connection than allow us to stumble into on our own), and more generally by having an openness to the magic and mystery of the dolls, without any of the adults' cynicism and meanness. And this is very unmistakably the whole message of Dolls, which celebrates the guilelessness of childhood play by making the grown-ups who belittle Judy's intelligence suffer greatly.

As far as that all goes, it's at least a slightly terrific movie. Gordon's directing treats this material with the utmost gravity, and the film's horror is always keyed to Judy. One of the most strikingly creepy images, repeated at least a couple of times, is entirely about the feeling of being a child in an adult world, with the camera high above Judy as she stands next to somebody much taller, exaggerating Lorraine's smallness within the frame and making her seem quite overwhelmed by everything around her. And as I've suggested, the things that happen are scary in the manner of a bunch of children - especially morbid children, perhaps - trying to freak each other out at a sleepover. "And then her eyes fell out!" "And then he saw blood on her slippers!" That kind of thing.

Truth be told, Dolls actually does manage to be pretty damn creepy, often enough. It's mostly because of the dolls themselves, shockingly expressive little buggers designed by John Brunner with a bit more flexibility in their eyes and mouths than your brain is quite willing to allow as a possibility. And the way that Gordon frames them, with help from cinematographer Mac Ahlberg (who quite gamely lights and frames for doll-scale close-ups, such that you start to forget they're props, not characters), and the way that editor Lee Percy pieces together the doll reaction shots, contribute to the altogether inescapable feeling that the little things are actually thinking, plotting, and nurturing their hate for those who disrespect the joy of childhood.

But even some of the non-doll moments work extremely well; early on, the first flush of Judy's imagination, as well as the first symptom of how broken and awful her family life is, comes in the form of a fantasy about a giant teddy bear ripping her father and stepmother apart. And you know what, seeing a person in a human-sized teddy bear costume emerging from the mist is just way the hell more uncanny and unnerving than seeing a blood-covered maniac with a knife, because of the sheer incongruity. The whole "nobody likes a clown at midnight" thing.

So in the face of all that, why can't I convince myself that Dolls is at least a moderate classic of fabulistic horror? Simple: it's too damn cheap. Or rather, it's cheap in debilitating ways - those dolls are magnificent creations, at least, and would be worthy in a much more prestigious production than this.

But the place where the cash shortage presents itself more obviously just hurt, so bad. One of these is the score, by Fuzzbee Morse, which is all the worst things about chintzy Casio keyboard synthetic music from low-budget and DTV horror in the '80s, despite an initially promising main theme (the credits, between the chiaroscuro lighting on disembodied doll heads, and Morse's ominously dreamy noodling, are full of a promise of atmosphere that the movie generally makes good on - but the music is all downhill from here). It's not worse than dozens or hundreds of other scores, but given how good Dolls is at rising above its Empire Pictures-level origins in so many ways, the constant aural reminder that nope, this is just a crummy no-budget indie horror joint is galling.

The other big problem is the cast. It's a weird shortcoming for the Gordon-Yuzna pairing, who had used no-name actors with extravagantly great results in both Re-Animator and From Beyond. But outside of the twinkle-eyed old folks playing a sweetness that disorientingly cuts against their role as menacing villains, and are both quite good (though I am maybe being generous to Mason with that "quite"), the cast is nothing but flat notes. Purdy-Gordon comes the closest to doing something with her role, though the necessary shortcomings of the "ice-cold rich bitch who'd as happily see her stepdaughter eaten by wolverines as not" figure mean that she can only go so far. And Lorraine is good more often than not, and I think it's probably more the direction than her that leads to her very bad scenes when she's overplaying the "I am an innocent child, pure of heart, with faith in the magical things in this world" card. The other four are all varying degrees of terrible: Lee overplays the same card that Lorraine does, and it's much less charming in an adult than a child, and there's nothing at all redeeming about Williams's one-note asshole nastiness, or Bailey and Stuart's arms race to see who can out-slattern the other.

The almost total lack of compelling human figures hobbles Dolls considerably, but it's not a killing blow: nuance-free shithead grown-ups fit the theme well enough that a more generous viewer than I might even regard it as a deliberate choice. Still, the flatness of everybody who isn't a potentially insane dollmaking warlock leaves the film with a hole where it's heart should be. And this is a very heart-driven horror movie, all things considered. I can only imagine liking it more on subsequent viewings - what works, works damn well, and what doesn't is a flaw common to literally tens of dozens of similar low-budget horror pictures, making it easier to overlook. Still, it's the first Stuart Gordon-Brian Yuzna film that isn't a home run, and easy to be a little more bitter at it for that reason, particularly given that Gordon and Yuzna, together and separately, never regained the mojo that they lost with this picture.