Blockbuster History: Incongruous vampires

Every Sunday this summer - and between the Year of Blood and a nightmarish stretch of shaky internet, I wasn't able to get this in on Sunday, but let's make believe - we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the chief selling points of Dark Shadows are that it is an update of an old TV show, and that it puts a vampire in a situation where you wouldn't expect a vampire to be, to comic effect. I have elected to follow the second path to a classic slice of teensploitation which also features bloodsuckers rather unceremoniously dropped into the world of American suburbia.

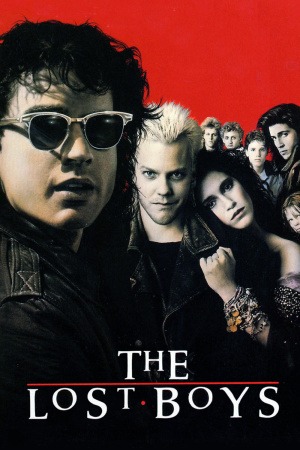

It is altogether fair to say that 1987's >The Lost Boys is nothing more than 93 minutes of set-up for its final line. And that would be a problem, except that the final line is so damned brilliant that even if nothing else in the film worked (and while it is hardly a great movie, it's good far more often than it's not), it would still be enough to justify the entire feature.

Said feature is significant for all sorts of reasons: it is the first movie to team The Two Coreys, teenagers Corey Feldman and Corey Haim, who went on to have quite a career as a duo because in the 1980s audiences just stone-cold did not give a fuck; and it puts up a really strong fight as being the best movie of director Joel Schumacher's career. So two reasons, and both of them kind of suck. But significance isn't really what The Lost Boys is aiming for; it is candy, in which a bunch of teenyboppers united under the guiding hand of the man whose last picture had been the epochal '80s teen movie St. Elmo's Fire. With vampires. It is the Twilight of its generation, only so much better, I can't even tell you - if nothing else, it was made at a time when vampires were still seductive but animalistic killers and monsters, and not brooding romantic heroes. I miss the hell out of those days.

Vampires, though, aren't really the point of The Lost Boys, but more like a condiment: as the St. Elmo's Fire/teen idol pedigree alerts us, this is actually much more of an adolescent rebellion melodrama, of the sort that American International Pictures made such a killing on in the 1950s and 1960s (vampires not being popular back in those days, they made do with a werewolf). The vampires are metaphors - and yes, vampires are almost always metaphors for something or other, but it's really particularly obvious and even strident in this case - for teenage hedonism and lack of self-control and the profound inability to plan for the future that is a necessary and constant part of being in your late teens and enjoying yourself. This is not my observation. The tagline on the film's poster already spells this out for us: "Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. Never die. It's fun to be a vampire." And besides that, the title itself is a straightforward Peter Pan reference, so it's not like Schumacher or any of the three credited writers were really trying to hide what's going on.

Here, Peter Pan is portrayed by David (Kiefer Sutherland), an adrenaline junkie with a shitty blond dye job; Wendy Darling is Michael (Jason Patric), who has just moved to the California coast town of Santa Carla with his recently divorced mother, Lucy (Dianne Wiest), along with younger brother Sam (Corey Haim). The lingering sense of the loss of sexual innocence that is sometimes held to be part of Peter Pan's theme is handled by Star (Jami Gertz), a young woman that Michael spots walking down the boardwalk one night, who seems to give him the go-ahead to follow her for flirting and potential making-out; but when he catches up with her, she appears to be David's girl, and part of his gang of thrill-seekers including Paul (Brooke McCarter), Dwayne (Billy Wirth), and Marko (Alex Winter).

Almost without thinking about it, Michael falls in with this crowd, drinking a rather ceremonial bottle of "wine" that does some very strange things to his head and body e.g. making it somewhat translucent in a mirror and shifting his sleep schedule so that he only ever wakes up at dusk and can't stand to have sunlight on his eyes. Sam, primed by the local comic book nerds and brothers Edgar Frog (Corey Feldman, adopting a deep gravelly voice that made me want to see him shoved into a trash compacter, though that is my customary response to '80s Feldman) and Alan Frog (Jamsion Newlander) that there be vampires in Santa Carla, immediately makes the connection, but fighting the Dark Ones when his brother is already half-vamped himself is more than the boy can handle, so first he must convince Michael of the curse he's under, before the two of them, aided by the Frogs, can fight David and his crew.

Writing it out like, though, makes it seem like The Lost Boys has a driven and cohesive plot, which isn't really the case: for a good solid hour, the filmmakers don't even come right out and say that David and his hangers-on are vampires or anything else besides particularly nihilistic punks (the ad campaign notwithstanding, I really can't get a sense of how long Schumacher actually anticipated his audience remaining in the dark about the paranormal nature of his antagonists). And most of that hour is spent establishing a mood and a mentality; as Sam pokes about, Michael isn't really doing much of anything besides falling deeper and deeper under David's spell, and the audience stands outside, watching him do it. The casting of Patric and Sutherland is a godsend to the film, though I expect for largely accidental reasons: Patric is such a bland, blank slate, and Sutherland has such intoxicating negative charisma - he's fascinating precisely because he's so disagreeable in every way - that their relationship has exactly the dangerous, predatory charge that the screenplay keeps implying without ever stating outright until it's time to kick off the third act. And for that matter, having such a wet noodle for our protagonist makes it easier for the viewer to ignore him and thus slide into his role, making David's seduction of Michael double as a seduction of ourselves.

Joel Schumacher has not ever, to my knowledge, been embraced as a queer filmmaker, and he shouldn't be: there's not much in his movies that can be stand up to that kind of analysis. But The Lost Boys has a significant, not to mention surprising, homoerotic charge that comes out of Sutherland's sharkish, nasty advances towards the mortal boy; Star, meant to be the object of Michael's erotic attraction, ends up hardly making an impression. This is not incidental to the film's success, not at all: as vampire picture, as latter-day juvenile delinquent shocker, as '80s teen lifestyle fantasy, and in pretty much every other register that we're likely to care about, the attraction between Michael and David is key to its success. Calling it a gay vampire film would be stupid on the face of it, of course, and while Schumacher isn't above sexualising all of his young male stars, I don't believe he's doing it deliberately, or systematically. And not all of the homoeroticism works: there is the famous matter of Sam's beefcake pin-up poster of Rob Lowe, inexplicably hanging right there where nobody ever comments on it. I do not object to films implicitly representing young teenagers as being homosexual; though I do object to films representing anybody at all as being sexually attracted to Rob Lowe. Regardless, it's hard not to wonder what the hell was going on in Schumacher's mind when he encouraged that bit of set design.

And it's not the only thing he does that doesn't work: aside from permitting Feldman to get away with that terrible, terrible accent, Schumacher relies on lazy directorial shorthand (there are no fewer than three functionally identical helicopter shots sweeping along the ocean and pulling up to show the Santa Carla boardwalk - a shot that was already tired in 1987 and gets a whole lot more tired before this movie finishes), and he fumbles the last act, when Michael and Sam barricade themselves in the house to fend off David and the vampire's attack; but the fact that a Schumacher film has some bad decisions in it is hardly distressing. That it has such intriguing character dynamics, meanwhile, is shocking as hell, and that the director handles the transitions between very light horror, comedy, teen romance, and action as well as he does is evidence of a sure hand found nowhere else in his filmography that I have seen.

In the grand scheme of things, this is obviously just a frothy teen picture, just edgy enough in its depiction of subcultures and violence to seem more cutting-edge than condescending, and just free enough with jokes that it's safe for non-fans of horror to come in, despite a considerable amount of blood for its presumptive target audience - then again, in the 1980s, teen films weren't half as sanitary and washed-out as they are now. The nervy sexual undercurrent to the whole thing makes it relatively unique among most of the films in the same wheelhouse from the same time, but it's such a small thing in the overall scheme of the movie.

Still, its fleet, and it's not nearly as stupid as "Peter Pan with vampires" could easily be, and like I said: great final line. I'm disinclined to call it anything other than well-made trash, but the key here is well-made: a breezy, fun teen genre film that's pleasurable without being taxing, and which has aged far better than most other '80s films of its ilk. I can't in good faith say that it is timeless classic and a must-see for everyone, but I've enjoyed myself every time I've seen it, and that will have to do as far as recommendations go.

It is altogether fair to say that 1987's >The Lost Boys is nothing more than 93 minutes of set-up for its final line. And that would be a problem, except that the final line is so damned brilliant that even if nothing else in the film worked (and while it is hardly a great movie, it's good far more often than it's not), it would still be enough to justify the entire feature.

Said feature is significant for all sorts of reasons: it is the first movie to team The Two Coreys, teenagers Corey Feldman and Corey Haim, who went on to have quite a career as a duo because in the 1980s audiences just stone-cold did not give a fuck; and it puts up a really strong fight as being the best movie of director Joel Schumacher's career. So two reasons, and both of them kind of suck. But significance isn't really what The Lost Boys is aiming for; it is candy, in which a bunch of teenyboppers united under the guiding hand of the man whose last picture had been the epochal '80s teen movie St. Elmo's Fire. With vampires. It is the Twilight of its generation, only so much better, I can't even tell you - if nothing else, it was made at a time when vampires were still seductive but animalistic killers and monsters, and not brooding romantic heroes. I miss the hell out of those days.

Vampires, though, aren't really the point of The Lost Boys, but more like a condiment: as the St. Elmo's Fire/teen idol pedigree alerts us, this is actually much more of an adolescent rebellion melodrama, of the sort that American International Pictures made such a killing on in the 1950s and 1960s (vampires not being popular back in those days, they made do with a werewolf). The vampires are metaphors - and yes, vampires are almost always metaphors for something or other, but it's really particularly obvious and even strident in this case - for teenage hedonism and lack of self-control and the profound inability to plan for the future that is a necessary and constant part of being in your late teens and enjoying yourself. This is not my observation. The tagline on the film's poster already spells this out for us: "Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. Never die. It's fun to be a vampire." And besides that, the title itself is a straightforward Peter Pan reference, so it's not like Schumacher or any of the three credited writers were really trying to hide what's going on.

Here, Peter Pan is portrayed by David (Kiefer Sutherland), an adrenaline junkie with a shitty blond dye job; Wendy Darling is Michael (Jason Patric), who has just moved to the California coast town of Santa Carla with his recently divorced mother, Lucy (Dianne Wiest), along with younger brother Sam (Corey Haim). The lingering sense of the loss of sexual innocence that is sometimes held to be part of Peter Pan's theme is handled by Star (Jami Gertz), a young woman that Michael spots walking down the boardwalk one night, who seems to give him the go-ahead to follow her for flirting and potential making-out; but when he catches up with her, she appears to be David's girl, and part of his gang of thrill-seekers including Paul (Brooke McCarter), Dwayne (Billy Wirth), and Marko (Alex Winter).

Almost without thinking about it, Michael falls in with this crowd, drinking a rather ceremonial bottle of "wine" that does some very strange things to his head and body e.g. making it somewhat translucent in a mirror and shifting his sleep schedule so that he only ever wakes up at dusk and can't stand to have sunlight on his eyes. Sam, primed by the local comic book nerds and brothers Edgar Frog (Corey Feldman, adopting a deep gravelly voice that made me want to see him shoved into a trash compacter, though that is my customary response to '80s Feldman) and Alan Frog (Jamsion Newlander) that there be vampires in Santa Carla, immediately makes the connection, but fighting the Dark Ones when his brother is already half-vamped himself is more than the boy can handle, so first he must convince Michael of the curse he's under, before the two of them, aided by the Frogs, can fight David and his crew.

Writing it out like, though, makes it seem like The Lost Boys has a driven and cohesive plot, which isn't really the case: for a good solid hour, the filmmakers don't even come right out and say that David and his hangers-on are vampires or anything else besides particularly nihilistic punks (the ad campaign notwithstanding, I really can't get a sense of how long Schumacher actually anticipated his audience remaining in the dark about the paranormal nature of his antagonists). And most of that hour is spent establishing a mood and a mentality; as Sam pokes about, Michael isn't really doing much of anything besides falling deeper and deeper under David's spell, and the audience stands outside, watching him do it. The casting of Patric and Sutherland is a godsend to the film, though I expect for largely accidental reasons: Patric is such a bland, blank slate, and Sutherland has such intoxicating negative charisma - he's fascinating precisely because he's so disagreeable in every way - that their relationship has exactly the dangerous, predatory charge that the screenplay keeps implying without ever stating outright until it's time to kick off the third act. And for that matter, having such a wet noodle for our protagonist makes it easier for the viewer to ignore him and thus slide into his role, making David's seduction of Michael double as a seduction of ourselves.

Joel Schumacher has not ever, to my knowledge, been embraced as a queer filmmaker, and he shouldn't be: there's not much in his movies that can be stand up to that kind of analysis. But The Lost Boys has a significant, not to mention surprising, homoerotic charge that comes out of Sutherland's sharkish, nasty advances towards the mortal boy; Star, meant to be the object of Michael's erotic attraction, ends up hardly making an impression. This is not incidental to the film's success, not at all: as vampire picture, as latter-day juvenile delinquent shocker, as '80s teen lifestyle fantasy, and in pretty much every other register that we're likely to care about, the attraction between Michael and David is key to its success. Calling it a gay vampire film would be stupid on the face of it, of course, and while Schumacher isn't above sexualising all of his young male stars, I don't believe he's doing it deliberately, or systematically. And not all of the homoeroticism works: there is the famous matter of Sam's beefcake pin-up poster of Rob Lowe, inexplicably hanging right there where nobody ever comments on it. I do not object to films implicitly representing young teenagers as being homosexual; though I do object to films representing anybody at all as being sexually attracted to Rob Lowe. Regardless, it's hard not to wonder what the hell was going on in Schumacher's mind when he encouraged that bit of set design.

And it's not the only thing he does that doesn't work: aside from permitting Feldman to get away with that terrible, terrible accent, Schumacher relies on lazy directorial shorthand (there are no fewer than three functionally identical helicopter shots sweeping along the ocean and pulling up to show the Santa Carla boardwalk - a shot that was already tired in 1987 and gets a whole lot more tired before this movie finishes), and he fumbles the last act, when Michael and Sam barricade themselves in the house to fend off David and the vampire's attack; but the fact that a Schumacher film has some bad decisions in it is hardly distressing. That it has such intriguing character dynamics, meanwhile, is shocking as hell, and that the director handles the transitions between very light horror, comedy, teen romance, and action as well as he does is evidence of a sure hand found nowhere else in his filmography that I have seen.

In the grand scheme of things, this is obviously just a frothy teen picture, just edgy enough in its depiction of subcultures and violence to seem more cutting-edge than condescending, and just free enough with jokes that it's safe for non-fans of horror to come in, despite a considerable amount of blood for its presumptive target audience - then again, in the 1980s, teen films weren't half as sanitary and washed-out as they are now. The nervy sexual undercurrent to the whole thing makes it relatively unique among most of the films in the same wheelhouse from the same time, but it's such a small thing in the overall scheme of the movie.

Still, its fleet, and it's not nearly as stupid as "Peter Pan with vampires" could easily be, and like I said: great final line. I'm disinclined to call it anything other than well-made trash, but the key here is well-made: a breezy, fun teen genre film that's pleasurable without being taxing, and which has aged far better than most other '80s films of its ilk. I can't in good faith say that it is timeless classic and a must-see for everyone, but I've enjoyed myself every time I've seen it, and that will have to do as far as recommendations go.

Categories: blockbuster history, summer movies, sunday classic movies, teen movies, vampires