Blockbuster History: Teensploitation

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: we're pretty much used to blockbuster movies such as the current perpetual money machine The Twilight Saga: Eclipse aiming either squarely or partially for a teenage audience, but such was not always the case. And as luck would have it, one of the key films in the development of our modern teen-centric cinema also happens to bet a thoroughly mercenary exploitation picture about a high school lycanthrope.

I could not do justice to the story of AIP in the space of a movie review, even if I never got around to the movie, but let it stand to say: James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff, who first formed American Releasing Corporation in 1955, did more for the subsequent history of film production than those two savvy executives, hungry for money far more than ever they looked for artistic or historical importance, would ever have dreamed possible. We are living in AIP's world, more than thirty years after AIP blinked out of existence.

It was a boom time for cheap programmers, back in the mid-'50s; but the sheer number of cheap drive-in movies meant that it took something really special to catch enough people's interest for long enough that any single movie would turn a decent profit. It was the particular genius of Arkoff and ARC/AIP (the name change happened in late 1956) to note that the bulk of B-moviegoers were teenagers, and yet very few movies of any stripe were made with a specific eye towards that audience. Thus it was than its first couple of years of existence, the company cranked out a truly mind-boggling number of pictures about teens and for teens, and by middle-aged white guys. AIP did more than any other outfit to promote the growth of the burgeoning "juvenile delinquency" genre; they were at the forefront of the "car racing" and "rock 'n roll" genres.

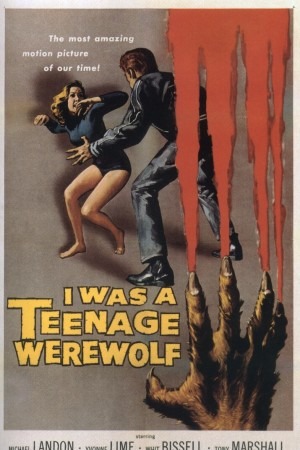

But the legacy of AIP is not just that they proved that the surest way to make money was to focus with laser-like intensity on teenage boys. Almost completely by accident, in the summer of 1957, a single AIP release that was neither more nor less cynical than any of those to precede came out, and made an amount of money that stunned even Arkoff and Nicholson. Titled I Was a Teenage Werewolf, it has generally been cited in later years as the first youth-oriented horror movie of any importance, and decades later its influence can be felt in every corner of horror filmmaking. So fully and so quickly did Hollywood absorb the lessons taught by this otherwise unexceptional bit of filler, that nowadays the most startling thing by far is to see a horror movie that seems to come from a genuinely adult perspective - even the nastiest hard-R gorefest still concerns itself with the suffering of young people and pitches itself towards the most undiscerning 17-year-olds.

With that kind of legacy, is it any surprise that I Was a Teenage Werewolf isn't any good? Its interest today is almost entirely academic - setting aside its nearly 60-year-old idea of what is "scary", I cannot imagine even the most forgiving modern horror fan overlooking how impenetrably slow-moving the first half is - proving, if any proof were needed, that the peculiar tendency for mega-hits to be kind of stupid and unnecessary held true so far back into history before the dawn of the modern Blockbuster Age that the mega-hit in question made $2,000,000 on a budget of $82,000. It also has value as a snapshot of the pressing sociological questions of 1957 - for Teenage Werewolf manages to cram more disparate strands of teenage experience than any other 76-minute film of its era - and as proved by the wits at Mystery Science Theater 3000, there's still plenty of entertainment to be pulled from the thing as long as you're willing to never, ever take it seriously.

Recalling that the film came from a distributor noted till then mostly for their juvenile delinquency films, it is very easy to break Teenage Werewolf into two parts: and the first of these is very little other than a routine JD movie, like so many of AIP's earlier efforts. Here we find Tony Rivers (Michael Landon), a troubled youth, whose particular trouble is that he's angry and lashes out violently. For example, when we meet him, he's scrapping with a kid much, much bigger than he is, and when the fight starts to go against him, he tries to pull out out a win by grabbing a shovel and wielding it menacingly. The local Decent Cop, one Donovan by name (Barney Phillips) proves to be surprisingly understanding of Tony's generally undirected anger, and suggests that the boy should have a chat with Dr. Brandon (Whit Bissell), a psychologist who often works with the police on delinquency cases. But Tony don't need nobody's help, and so he angrily stomps off to a Halloween party that night with his best girl Arlene (Yvonne Fedderson). At the party, Tony plays practical jokes on just about everybody, but when he's on the receiving end, he flails out wildly and the ensuing melee is enough to convince him that he does have a serious problem, and Dr. Brandon might be the only one who can help him.

And that choice kicks off the second half of the movie, because Dr. Brandon proves to be an unusually pure example of the mad scientist beloved of '50s genre films - the kind who won't let simple, proletarian concerns like "ethics", "practicality", or "making any goddamn sense" stand between them and The Inexorable Advance Of Knowledge. And this is why he has invented a serum that can regress humans back into wolves, recognising that there was no other way to keep humanity from destroying itself. Before you can say, "what the living hell are you talking about?", Tony has become a wolf-man, killing two of his classmates, and escaping the police - who seem remarkably unruffled by the presence of a fairy-tale monster in their community - by running into the woods.

Only two things stand between Teenage Werewolf and complete irrelevance - which is, by all means, two more than we find in most '50s monster movies - and these are Whit Bissell and Michael Landon. Though neither of them give a performance for the ages, so too are they both entirely solid and respectable - Landon even got himself a three-decade career out of it, finding his way into the cast of Bonanza on the strength of his performance and matinee idol looks. Bissell in particular gives a rather definitive take on a certain kind of mad scientist, the one who is all business and seriousness. No raving about the fools back at the university who wouldn't listen in this monster movie!

It's as a mad scientist film that Teenage Werewolf is generally the most satisfying, in fact, and largely because of the slightly unconventional portrayal of the mad scientist. It's a common observation that '50s science fiction looks on scientific advance with a certain fear: but by stripping Dr. Brandon of the usual melodramatic signifiers of villainy, Teenage Werewolf does a much more thorough job than usual of indicting the scientific community. For a mad scientist, Brandon is unusually committed to the scientific method, or at least, he's unusually committed to explain why each and every bizarre-ass thing he does is Good Science that will be well-received in all the journals. He does this, of course, without ever explaining how world peace will come about if all the sullen young men are turned into raging wolf-beasts, but our stupid little minds would doubtlessly not keep up with Brandon's genius.

The film's depiction of Brandon as the ultimate Man of Science reaches its apogee in a classic exchange with his mildewy humanist assistant, Hugo (Jospeh Mell), dialogue so brilliantly stupid that Lyz Kingsley, herself a scientist and one of the best B-movie reviewers on the internet, stole it as the title for her website:

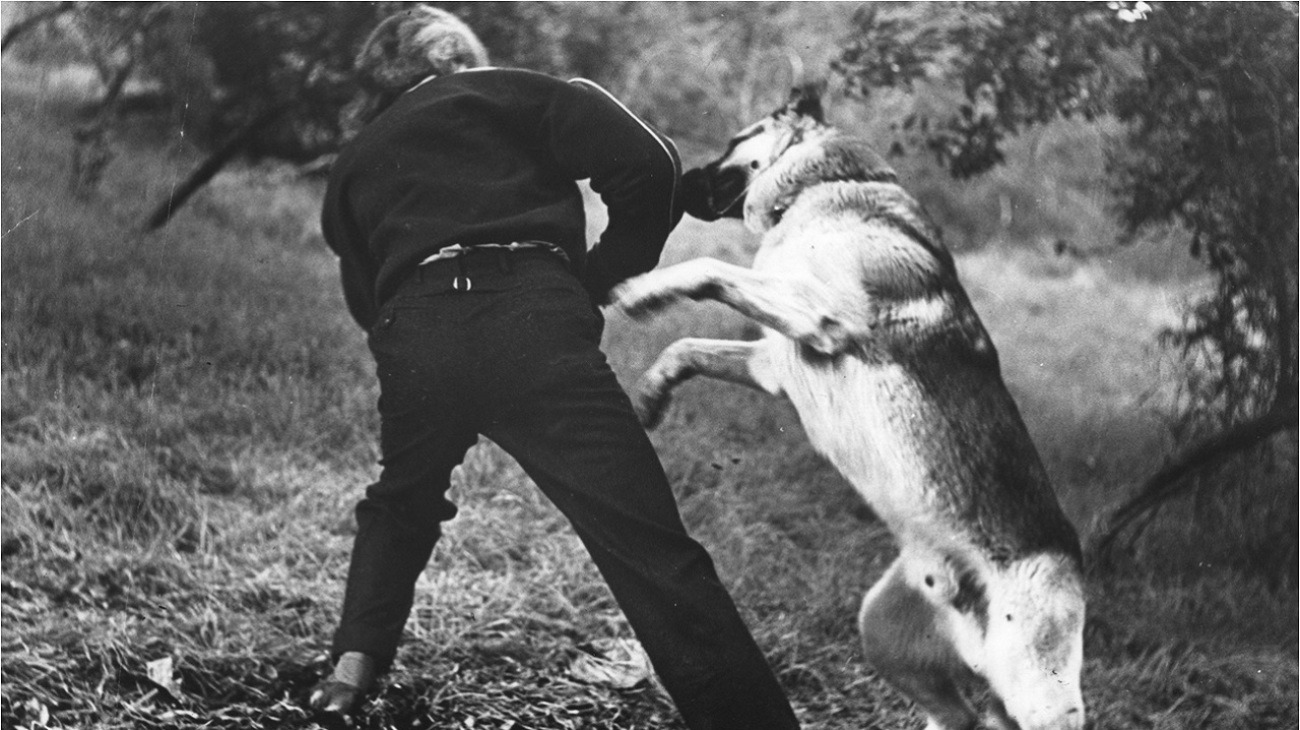

If the mad science angle of Teenage Werewolf thus manages to achieve a kind of thrilling Awesome Bad Movie insipidness, neither the teenage parts nor the werewolf parts do the same. In the case of the latter, it's easy enough to explain why: besides make-up that is a lazy steal from Universal's iconic The Wolf Man, the writers Herman Cohen and Aben Kandel, and director Gene Fowler, Jr. don't have any idea what to do with their wolf once he shows up - far too deep into the movie to salvage it. Tony's big lycanthropy spree finds him mostly in hiding, as the cops ask after him and comb the forest; absent a wonderfully incompetent fight between the teenage werewolf and a fake German Shepherd, the movie sinks into rampant dullness for nearly all of the wolfman action. Which, to be fair, is exactly where it started out: indeed, the juvenile delinquent plot, that grinds along and along and along and along and makes the 76-minute feature seem half again as long as that, is duller still. Part of this is Fowler's cost-saving decision to shoot as much of the film as possible in long takes of people looking at each other and talking. It's the sort of visual stagnation that you don't have to notice in order to feel the effects: nothing happens, stretched out to infinity. The only time that the film picks up at all in the first 30 minutes is the Halloween party, which is still shot to be as boring as possible, but at least has an incomprehensibly weird song, "Eeny Meeny Miney Moe", to distract the viewer from the boilerplate JD theatrics. Nothing is quite as much fun as watching what grown-ups thought beatniks acted like.

It would be easy enough to blame all this on the film's age; but I think Teenage Werewolf has greater issues than just changing tastes. Its slowness is the result of cheapness, the result of having precious little sizzle and no steak, and having to make that go as far as possible (the AIP trick of coming up with a title and poster before a screenplay was even written hadn't come into being yet, but the film feels exactly like most of their work in that mode: only the promise of a teenage werewolf makes the endless JD scenes even marginally tolerable). In 1957, raw novelty was enough to boost the film to unheard-of financial success, but novelty is one thing very much not on the film's side any more. But at least, compared to the equally boring and often much less conceptually innovative movies that so often rule the weekend box office these days, it's hella short.

1. A younger child will watch anything that an older one will watch.American International Pictures! - Ay, Eye, Pee - three little letters that flow together with urgent easiness, a coruscation of vowels and that one puffy little consonant giving the phrase a bit of a hop, just the slightest lift on its twinkling way past the lips. American International Pictures, AIP, and just to hear the sound, just to see the words appear onscreen, this is enough to make a savvy B-movie viewer catch her breath, or feel his heart stop for a moment. For American International Pictures means that what you are about to watch will be absolutely wonderful and delightful, or else will be incredibly, indecently bad.

2. An older child will not watch anything a younger child will watch.

3. A girl will watch anything a boy will watch.

4. A boy will not watch anything a girl will watch.

5. In order to catch your greatest audience, you zero in on a 19-year-old male.

-The "Peter Pan Syndrome" formulated by AIP

I could not do justice to the story of AIP in the space of a movie review, even if I never got around to the movie, but let it stand to say: James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff, who first formed American Releasing Corporation in 1955, did more for the subsequent history of film production than those two savvy executives, hungry for money far more than ever they looked for artistic or historical importance, would ever have dreamed possible. We are living in AIP's world, more than thirty years after AIP blinked out of existence.

It was a boom time for cheap programmers, back in the mid-'50s; but the sheer number of cheap drive-in movies meant that it took something really special to catch enough people's interest for long enough that any single movie would turn a decent profit. It was the particular genius of Arkoff and ARC/AIP (the name change happened in late 1956) to note that the bulk of B-moviegoers were teenagers, and yet very few movies of any stripe were made with a specific eye towards that audience. Thus it was than its first couple of years of existence, the company cranked out a truly mind-boggling number of pictures about teens and for teens, and by middle-aged white guys. AIP did more than any other outfit to promote the growth of the burgeoning "juvenile delinquency" genre; they were at the forefront of the "car racing" and "rock 'n roll" genres.

But the legacy of AIP is not just that they proved that the surest way to make money was to focus with laser-like intensity on teenage boys. Almost completely by accident, in the summer of 1957, a single AIP release that was neither more nor less cynical than any of those to precede came out, and made an amount of money that stunned even Arkoff and Nicholson. Titled I Was a Teenage Werewolf, it has generally been cited in later years as the first youth-oriented horror movie of any importance, and decades later its influence can be felt in every corner of horror filmmaking. So fully and so quickly did Hollywood absorb the lessons taught by this otherwise unexceptional bit of filler, that nowadays the most startling thing by far is to see a horror movie that seems to come from a genuinely adult perspective - even the nastiest hard-R gorefest still concerns itself with the suffering of young people and pitches itself towards the most undiscerning 17-year-olds.

With that kind of legacy, is it any surprise that I Was a Teenage Werewolf isn't any good? Its interest today is almost entirely academic - setting aside its nearly 60-year-old idea of what is "scary", I cannot imagine even the most forgiving modern horror fan overlooking how impenetrably slow-moving the first half is - proving, if any proof were needed, that the peculiar tendency for mega-hits to be kind of stupid and unnecessary held true so far back into history before the dawn of the modern Blockbuster Age that the mega-hit in question made $2,000,000 on a budget of $82,000. It also has value as a snapshot of the pressing sociological questions of 1957 - for Teenage Werewolf manages to cram more disparate strands of teenage experience than any other 76-minute film of its era - and as proved by the wits at Mystery Science Theater 3000, there's still plenty of entertainment to be pulled from the thing as long as you're willing to never, ever take it seriously.

Recalling that the film came from a distributor noted till then mostly for their juvenile delinquency films, it is very easy to break Teenage Werewolf into two parts: and the first of these is very little other than a routine JD movie, like so many of AIP's earlier efforts. Here we find Tony Rivers (Michael Landon), a troubled youth, whose particular trouble is that he's angry and lashes out violently. For example, when we meet him, he's scrapping with a kid much, much bigger than he is, and when the fight starts to go against him, he tries to pull out out a win by grabbing a shovel and wielding it menacingly. The local Decent Cop, one Donovan by name (Barney Phillips) proves to be surprisingly understanding of Tony's generally undirected anger, and suggests that the boy should have a chat with Dr. Brandon (Whit Bissell), a psychologist who often works with the police on delinquency cases. But Tony don't need nobody's help, and so he angrily stomps off to a Halloween party that night with his best girl Arlene (Yvonne Fedderson). At the party, Tony plays practical jokes on just about everybody, but when he's on the receiving end, he flails out wildly and the ensuing melee is enough to convince him that he does have a serious problem, and Dr. Brandon might be the only one who can help him.

And that choice kicks off the second half of the movie, because Dr. Brandon proves to be an unusually pure example of the mad scientist beloved of '50s genre films - the kind who won't let simple, proletarian concerns like "ethics", "practicality", or "making any goddamn sense" stand between them and The Inexorable Advance Of Knowledge. And this is why he has invented a serum that can regress humans back into wolves, recognising that there was no other way to keep humanity from destroying itself. Before you can say, "what the living hell are you talking about?", Tony has become a wolf-man, killing two of his classmates, and escaping the police - who seem remarkably unruffled by the presence of a fairy-tale monster in their community - by running into the woods.

Only two things stand between Teenage Werewolf and complete irrelevance - which is, by all means, two more than we find in most '50s monster movies - and these are Whit Bissell and Michael Landon. Though neither of them give a performance for the ages, so too are they both entirely solid and respectable - Landon even got himself a three-decade career out of it, finding his way into the cast of Bonanza on the strength of his performance and matinee idol looks. Bissell in particular gives a rather definitive take on a certain kind of mad scientist, the one who is all business and seriousness. No raving about the fools back at the university who wouldn't listen in this monster movie!

It's as a mad scientist film that Teenage Werewolf is generally the most satisfying, in fact, and largely because of the slightly unconventional portrayal of the mad scientist. It's a common observation that '50s science fiction looks on scientific advance with a certain fear: but by stripping Dr. Brandon of the usual melodramatic signifiers of villainy, Teenage Werewolf does a much more thorough job than usual of indicting the scientific community. For a mad scientist, Brandon is unusually committed to the scientific method, or at least, he's unusually committed to explain why each and every bizarre-ass thing he does is Good Science that will be well-received in all the journals. He does this, of course, without ever explaining how world peace will come about if all the sullen young men are turned into raging wolf-beasts, but our stupid little minds would doubtlessly not keep up with Brandon's genius.

The film's depiction of Brandon as the ultimate Man of Science reaches its apogee in a classic exchange with his mildewy humanist assistant, Hugo (Jospeh Mell), dialogue so brilliantly stupid that Lyz Kingsley, herself a scientist and one of the best B-movie reviewers on the internet, stole it as the title for her website:

DR. BRANDON: I'm going to take this out of the realm of possibilities, into the world of exact science! If I'm successful, then I can be certain.This is the crescendo of a theme that plays throughout the movie: scientists are so eager to scientifically do science that they will kill you without a moment's thought. Readily found throughout the '50s, and beyond, but rarely expressed so baldly.

HUGO: But you're sacrificing a human life!

DR. BRANDON: Do you cry over a guinea pig? This boy is a free police case, we're probably saving him from the gas chamber.

HUGO: But the boy is so young, and the transformation horrible...

DR. BRANDON: And you call yourself a scientist! That's why you've never been more than an assistant.

If the mad science angle of Teenage Werewolf thus manages to achieve a kind of thrilling Awesome Bad Movie insipidness, neither the teenage parts nor the werewolf parts do the same. In the case of the latter, it's easy enough to explain why: besides make-up that is a lazy steal from Universal's iconic The Wolf Man, the writers Herman Cohen and Aben Kandel, and director Gene Fowler, Jr. don't have any idea what to do with their wolf once he shows up - far too deep into the movie to salvage it. Tony's big lycanthropy spree finds him mostly in hiding, as the cops ask after him and comb the forest; absent a wonderfully incompetent fight between the teenage werewolf and a fake German Shepherd, the movie sinks into rampant dullness for nearly all of the wolfman action. Which, to be fair, is exactly where it started out: indeed, the juvenile delinquent plot, that grinds along and along and along and along and makes the 76-minute feature seem half again as long as that, is duller still. Part of this is Fowler's cost-saving decision to shoot as much of the film as possible in long takes of people looking at each other and talking. It's the sort of visual stagnation that you don't have to notice in order to feel the effects: nothing happens, stretched out to infinity. The only time that the film picks up at all in the first 30 minutes is the Halloween party, which is still shot to be as boring as possible, but at least has an incomprehensibly weird song, "Eeny Meeny Miney Moe", to distract the viewer from the boilerplate JD theatrics. Nothing is quite as much fun as watching what grown-ups thought beatniks acted like.

It would be easy enough to blame all this on the film's age; but I think Teenage Werewolf has greater issues than just changing tastes. Its slowness is the result of cheapness, the result of having precious little sizzle and no steak, and having to make that go as far as possible (the AIP trick of coming up with a title and poster before a screenplay was even written hadn't come into being yet, but the film feels exactly like most of their work in that mode: only the promise of a teenage werewolf makes the endless JD scenes even marginally tolerable). In 1957, raw novelty was enough to boost the film to unheard-of financial success, but novelty is one thing very much not on the film's side any more. But at least, compared to the equally boring and often much less conceptually innovative movies that so often rule the weekend box office these days, it's hella short.