Fresh cuts

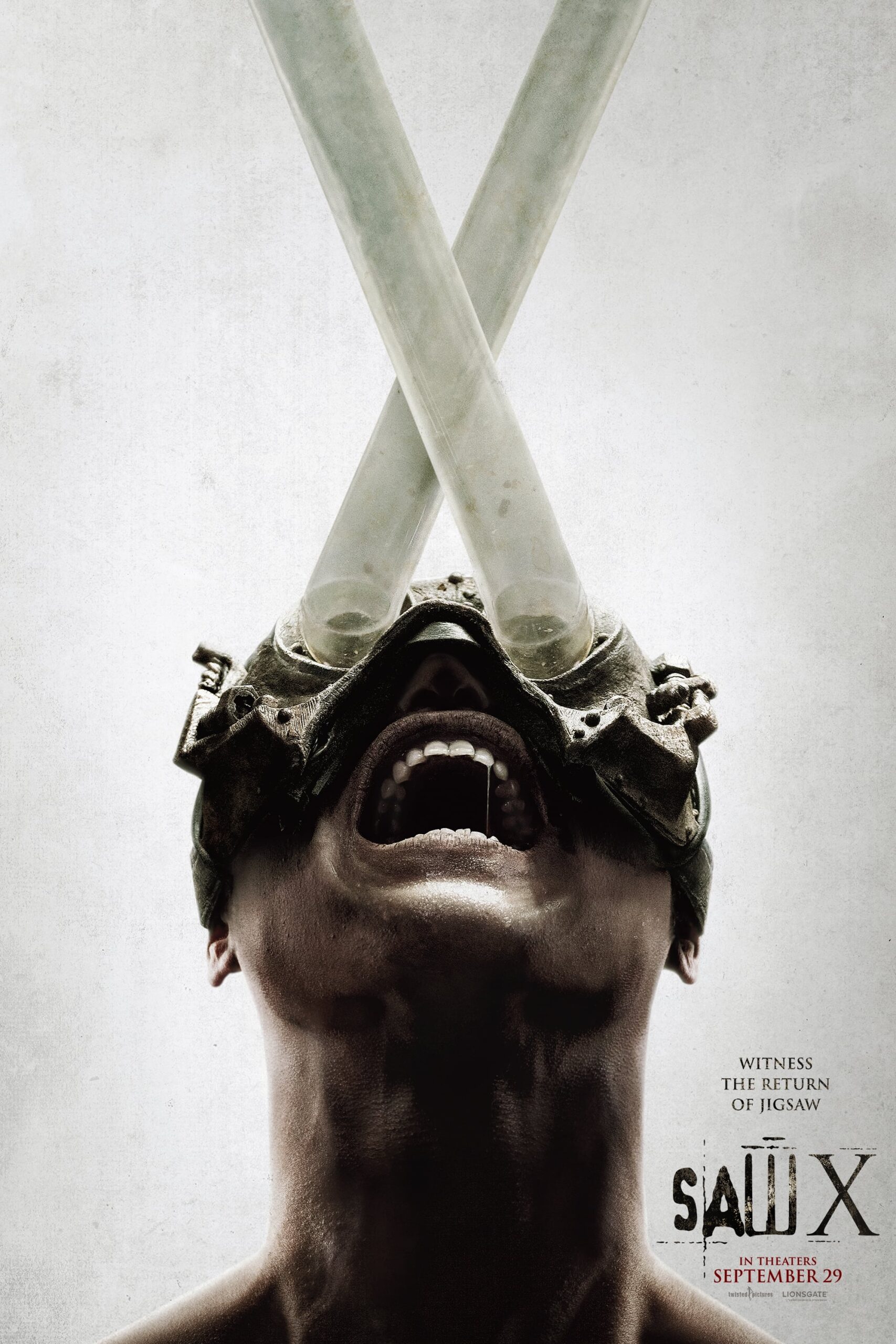

There are two claims I would like to make about Saw X, and both of them surprise the hell out of me. The weaker claim, which is still a bit on the aggressive side, is that Saw X is the best of the ten Saw films stretching back to 2004, though the series has been strictly in "soft reboots and legacy sequels" territory since Saw 3D ended the main run of the movies as a once-per-year Halloween tradition. The stronger claim is that Saw X is the first-ever actually good Saw movie, which I say advisedly; I know of people, including those whose opinions on horror I take very seriously, who think that at least the first Saw, and sometimes also 2005's Saw II, are good enough, with the first one maybe even being a proper horror classic (I imagine the other seven entries have defenders, but they don't defend them in front of me). I have not had a kindly relationship with the Saw pictures; I have found they range between jankily-made if conceptually audacious exercises in splatter, down to wholly unintelligible displays of arbitrarily disgusting imagery that have disappeared deep inside their own asshole with an ever-more-convoluted pile-up of needlessly difficult, chronologically-fragmented lore. And at all points on this none-too-expansive spectrum, they've always struck me as too proud of their childishly nihilistic attitude to have any real bite as horror.

So maybe my opinion shouldn't matter, but it's terrifically favorable anyways. Saw X answers both of my big complaints just given: it wipes clean all of that accumulated narrative messiness by rolling back the clock eight films and eighteen years, taking place chronologically after Saw and only Saw (though it also implicitly expects you to have seen Saw II and Saw IV). It's not an especially nihilistic film at all; it is, in fact, quite unexpectedly a very feeling sort of movie, though there's a lot of ugliness and discomfort involved in the feelings raised, since they are directly inviting us to have a nice time empathising with a deranged serial killer. It's a genuinely solid little character piece, weirdly, for the first time in ten entries making the series' characteristic "games" - torture traps that you can only survive if you're willing to do something extreme but not precisely fatal in order to karmically answer to John "Jigsaw" Kramer (Tobin Bell), who has decided that he is the only moral authority left in a fallen, craven world; these "games" often involve multiple traps in a row that have been laid out in a narratively suggestive order around the most squalid-looking warehouses you ever did see - as I was saying, making the "games" feel actually emotionally resonant to us the viewer, and not just like particularly bloody EC Comics splash pages.

The path that Saw X traveled to become the best-ever Saw movie was short, brightly-lit, well-marked and so obvious that it's a little revolting that nobody involved thought to take it by now: make Bell the protagonist. That's seriously it. It's been clear since 2004 to anyone who wanted to notice it that Bell was the best actor in all of the movies where he appeared with anything resembling an actual part (the only Bell-free movie was 2021's Spiral: From the the Book of Saw, though in some of the films where he does appear, Bell got little more than a cameo), but until this point he's always been the shadowy villain, sometimes having a lot to do and say and sometimes having very little, but never actually standing front and center as the focal point of the action. And now he's been made that focal point, and just like that, Saw X is the most narratively interesting and successfully character-oriented (and, 118 minutes, the longest) Saw movie yet. Funny how that works.

The particular tale spun by Saw X is one of cynicism being unwillingly replaced with wary hope, and the crushing, feverish hate that sweeps in once that hope has been revealed as a sham. In those days, John Kramer had already made quite a splash with his warped mirror version of moral lessons, having come up with his blood-soaked theories as a result of receiving a terminal diagnosis of brain cancer. When we catch up with him at the start of this film (written by the team of Pete Goldfinger & Josh Stolberg, who were also behind the other two "legacy" Saw sequels, Spiral and 2017's Jigsaw), that terminal diagnosis has been moved up quite a bit: he has in fact been told that he has only months to live. This casts him into a depressive funk, until he crosses paths with a man by the name of Henry (Michael Beach), who had once been in the same cancer patient support group as Kramer. In the intervening weeks, Henry has been cured, thanks to the miraculous - but highly scientific - and, most importantly, highly illegal in all countries - work being done by Cecilia Pederson (Synnøve Macody Lund), the daughter of a maverick Norwegian medical genius. Kramer is desperate enough to grasp onto any hope at all that he uses the information from Henry to track Cecilia down, agreeing to meet her in a secret hidey-hole somewhere in Mexico City. Here he is, he thinks, treated - but while trying to find the underground clinic later on in order to provide a thank you gift to the kindhearted Gabriela (Renata Vaca), one of Cecilia's aides, he instead finds the hastily-abandoned wreckage of an elaborate con designed to extract the desperately optimistic from their money. And this, of course, does not sit at all well with Kramer, so the next time we see him, he and his right-hand woman, Amanda Young (Shawnee Smith) have put into motion a game that will stop Cecilia's long con in the most gory way necessary, while having the very happy additional effect of giving Kramer some much-wanted revenge - enough for Amanda to start growing concerned that this situation is so personal that her mentor is at risk of losing sight of the strict rules governing the running of their games. Which neatly bleeds into her character arc from Saw III, and it's obviously no great feat to foreshadow a sequel that already came out 17 years ago, but I do appreciate that Saw X has had the knock-on effect of making me want to reconsider my stance towards had previously been my least-favorite movie in the series.

The simpler way of putting all of the above is that Saw X is more interested in what it does to Kramer (and to a lesser extent Amanda) to concoct and execute these torture chambers than in the minds and behaviors of the people being tortured. This works spectacularly well, mostly because Bell and Smith are good enough to justify putting that kind of emphasis on the psychology of their characters (Smith, who has made fewer trips back to the franchise than Bell since the movie where both of their characters died, is a little bit wobbly in the role, but in a way that comfortably fits Amanda's function in the story; the bigger issue is that the actor is sometimes struggling to return to the hotheaded brashness of the role she created when she was 19 years younger, and the fucking horrendous bob wig the makeup team crudely deposited on her head isn't helping her out any). But it also lets the film have a distinct "back to basics" attitude. For the first time since the 2004 kick-off to the series, we have a Saw film in which the bulk of the game takes place in a single room, so something like half of this long-for-Saw movie is basically just on a single set. Two, if you count the control room overlooking the warehouse floor with all of the torture devices as a second set. Either way, this is awfully stripped down from the mysterious industrial rabbit warrens where most of the films have set their plots, and it points to how much less exhaustingly baroque this film is than most of the earlier sequels. One of the charms, if that's the word, of the Saw sequels has been the gaudy complexity of the death traps; while Saw X is certainly closer to any of the other sequels than the stripped-to-the-bone scenario of the first Saw, it would be fair to argue that this is about as disinterested as these films get in the wild extravagance of its traps. The most excessively goofy in its macabre theatrics is only seen in a dream, and two-fifths of the traps in the real world are just variations on "how fast can you perform surgery on your own body? Ooh, that wasn't fast enough". The most visually distinctive is the last, and that has less to do with the trap than the massive quantities of blood involved, and it's not even blood from anybody involved in the game.

I frankly don't see any of this as a problem. The Grand Guignol elements of the Saw movies have always been their draw, but that's because they weren't really trying to sell anything else, unless you count the confusing, labyrinthine plotting and disordered chronology of the series as positive things. Saw X has a terrific performance of a murderous madman growing soft and warm before growing extremely hard and cold to recommend itself, as well as a very gnarly journey of audience identification attached to that madman: by making Cecilia such an outrageously horrible figure, the film severely complicates our relationship to Kramer, because we can't help but sympathise with the ferocious hate he feels for her. And things get even more complicated with Gabriela, who Kramer obviously likes best, and thus feels most betrayed by, but it's also hard not to notice (Amanda certainly seems to) that he gives her by far the easiest trap to survive. It's kind of an inversion of the usual morality play: instead of watching a good man wrestle with the evil inside of him, we're watching an evil man wrestling with his impulses towards warmth and affection. Bell is doing great work here, far and away the best performance he's given in this series, and not only because he has so much more screentime.

It's a pretty fascinating character study, and the movie mostly supports it. Director Kevin Greutert has previously been responsible for arguably the best of all the sequels with 2009's Saw VI and arguably the worst of all the sequels with 2010s Saw 3D, and as far as wringing out the horrific thrills from this one, he's not operating at peak performance: the traps don't have the real squirmy quality that the best Saw setpieces do, and it feels in most cases like it costs the characters very little to saw through their own legs or mash their arms with hammers or whatnot. The film's pacing goes terribly slack at the end; the series' formula makes it pretty clear pretty quickly after the third of four traps has been sprung where this is going, but it takes an awfully large number of those 118 minutes to get there. On the other hand, Greutert turns out to have a steady hand with character beats; watching Bell, with staring red-rimmed eyes, wallow in existential sadness, is worth all of the indulgent time the film spends on it, and Greutert helps the film successfully navigate its surprising turn towards mildly comic warmth in the middle section where Kramer thinks that he's beaten the cancer. It's an injection of earnestly light material that nevertheless needs to feel weighted in the gravity of the series - a Saw movie might be able to sell "mildly comic", but it's not selling "flippant and insincere" - and while it would feel very obtuse to call it the "best" part of the movie, it is maybe the most striking in that it is so unexpected, but carried off so smoothly. Kind of miraculous to find that this of all franchises is willing and able to make unexpected swerves ten entries in and I am surprised to find myself thinking, very much for the first time in 19 years: I do hope they get a chance to make another one.

Reviews in this series

Saw (Wan, 2004)

Saw II (Bousman, 2005)

Saw III (Bousman, 2006)

Saw IV (Bousman, 2007)

Saw V (Hackl, 2008)

Saw VI (Greutert, 2009)

Saw 3D (Greutert, 2010)

Jigsaw (Spierig Brothers, 2017)

Spiral: From the Book of Saw (Bousman, 2021)

Saw X (Greutert, 2023)

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

So maybe my opinion shouldn't matter, but it's terrifically favorable anyways. Saw X answers both of my big complaints just given: it wipes clean all of that accumulated narrative messiness by rolling back the clock eight films and eighteen years, taking place chronologically after Saw and only Saw (though it also implicitly expects you to have seen Saw II and Saw IV). It's not an especially nihilistic film at all; it is, in fact, quite unexpectedly a very feeling sort of movie, though there's a lot of ugliness and discomfort involved in the feelings raised, since they are directly inviting us to have a nice time empathising with a deranged serial killer. It's a genuinely solid little character piece, weirdly, for the first time in ten entries making the series' characteristic "games" - torture traps that you can only survive if you're willing to do something extreme but not precisely fatal in order to karmically answer to John "Jigsaw" Kramer (Tobin Bell), who has decided that he is the only moral authority left in a fallen, craven world; these "games" often involve multiple traps in a row that have been laid out in a narratively suggestive order around the most squalid-looking warehouses you ever did see - as I was saying, making the "games" feel actually emotionally resonant to us the viewer, and not just like particularly bloody EC Comics splash pages.

The path that Saw X traveled to become the best-ever Saw movie was short, brightly-lit, well-marked and so obvious that it's a little revolting that nobody involved thought to take it by now: make Bell the protagonist. That's seriously it. It's been clear since 2004 to anyone who wanted to notice it that Bell was the best actor in all of the movies where he appeared with anything resembling an actual part (the only Bell-free movie was 2021's Spiral: From the the Book of Saw, though in some of the films where he does appear, Bell got little more than a cameo), but until this point he's always been the shadowy villain, sometimes having a lot to do and say and sometimes having very little, but never actually standing front and center as the focal point of the action. And now he's been made that focal point, and just like that, Saw X is the most narratively interesting and successfully character-oriented (and, 118 minutes, the longest) Saw movie yet. Funny how that works.

The particular tale spun by Saw X is one of cynicism being unwillingly replaced with wary hope, and the crushing, feverish hate that sweeps in once that hope has been revealed as a sham. In those days, John Kramer had already made quite a splash with his warped mirror version of moral lessons, having come up with his blood-soaked theories as a result of receiving a terminal diagnosis of brain cancer. When we catch up with him at the start of this film (written by the team of Pete Goldfinger & Josh Stolberg, who were also behind the other two "legacy" Saw sequels, Spiral and 2017's Jigsaw), that terminal diagnosis has been moved up quite a bit: he has in fact been told that he has only months to live. This casts him into a depressive funk, until he crosses paths with a man by the name of Henry (Michael Beach), who had once been in the same cancer patient support group as Kramer. In the intervening weeks, Henry has been cured, thanks to the miraculous - but highly scientific - and, most importantly, highly illegal in all countries - work being done by Cecilia Pederson (Synnøve Macody Lund), the daughter of a maverick Norwegian medical genius. Kramer is desperate enough to grasp onto any hope at all that he uses the information from Henry to track Cecilia down, agreeing to meet her in a secret hidey-hole somewhere in Mexico City. Here he is, he thinks, treated - but while trying to find the underground clinic later on in order to provide a thank you gift to the kindhearted Gabriela (Renata Vaca), one of Cecilia's aides, he instead finds the hastily-abandoned wreckage of an elaborate con designed to extract the desperately optimistic from their money. And this, of course, does not sit at all well with Kramer, so the next time we see him, he and his right-hand woman, Amanda Young (Shawnee Smith) have put into motion a game that will stop Cecilia's long con in the most gory way necessary, while having the very happy additional effect of giving Kramer some much-wanted revenge - enough for Amanda to start growing concerned that this situation is so personal that her mentor is at risk of losing sight of the strict rules governing the running of their games. Which neatly bleeds into her character arc from Saw III, and it's obviously no great feat to foreshadow a sequel that already came out 17 years ago, but I do appreciate that Saw X has had the knock-on effect of making me want to reconsider my stance towards had previously been my least-favorite movie in the series.

The simpler way of putting all of the above is that Saw X is more interested in what it does to Kramer (and to a lesser extent Amanda) to concoct and execute these torture chambers than in the minds and behaviors of the people being tortured. This works spectacularly well, mostly because Bell and Smith are good enough to justify putting that kind of emphasis on the psychology of their characters (Smith, who has made fewer trips back to the franchise than Bell since the movie where both of their characters died, is a little bit wobbly in the role, but in a way that comfortably fits Amanda's function in the story; the bigger issue is that the actor is sometimes struggling to return to the hotheaded brashness of the role she created when she was 19 years younger, and the fucking horrendous bob wig the makeup team crudely deposited on her head isn't helping her out any). But it also lets the film have a distinct "back to basics" attitude. For the first time since the 2004 kick-off to the series, we have a Saw film in which the bulk of the game takes place in a single room, so something like half of this long-for-Saw movie is basically just on a single set. Two, if you count the control room overlooking the warehouse floor with all of the torture devices as a second set. Either way, this is awfully stripped down from the mysterious industrial rabbit warrens where most of the films have set their plots, and it points to how much less exhaustingly baroque this film is than most of the earlier sequels. One of the charms, if that's the word, of the Saw sequels has been the gaudy complexity of the death traps; while Saw X is certainly closer to any of the other sequels than the stripped-to-the-bone scenario of the first Saw, it would be fair to argue that this is about as disinterested as these films get in the wild extravagance of its traps. The most excessively goofy in its macabre theatrics is only seen in a dream, and two-fifths of the traps in the real world are just variations on "how fast can you perform surgery on your own body? Ooh, that wasn't fast enough". The most visually distinctive is the last, and that has less to do with the trap than the massive quantities of blood involved, and it's not even blood from anybody involved in the game.

I frankly don't see any of this as a problem. The Grand Guignol elements of the Saw movies have always been their draw, but that's because they weren't really trying to sell anything else, unless you count the confusing, labyrinthine plotting and disordered chronology of the series as positive things. Saw X has a terrific performance of a murderous madman growing soft and warm before growing extremely hard and cold to recommend itself, as well as a very gnarly journey of audience identification attached to that madman: by making Cecilia such an outrageously horrible figure, the film severely complicates our relationship to Kramer, because we can't help but sympathise with the ferocious hate he feels for her. And things get even more complicated with Gabriela, who Kramer obviously likes best, and thus feels most betrayed by, but it's also hard not to notice (Amanda certainly seems to) that he gives her by far the easiest trap to survive. It's kind of an inversion of the usual morality play: instead of watching a good man wrestle with the evil inside of him, we're watching an evil man wrestling with his impulses towards warmth and affection. Bell is doing great work here, far and away the best performance he's given in this series, and not only because he has so much more screentime.

It's a pretty fascinating character study, and the movie mostly supports it. Director Kevin Greutert has previously been responsible for arguably the best of all the sequels with 2009's Saw VI and arguably the worst of all the sequels with 2010s Saw 3D, and as far as wringing out the horrific thrills from this one, he's not operating at peak performance: the traps don't have the real squirmy quality that the best Saw setpieces do, and it feels in most cases like it costs the characters very little to saw through their own legs or mash their arms with hammers or whatnot. The film's pacing goes terribly slack at the end; the series' formula makes it pretty clear pretty quickly after the third of four traps has been sprung where this is going, but it takes an awfully large number of those 118 minutes to get there. On the other hand, Greutert turns out to have a steady hand with character beats; watching Bell, with staring red-rimmed eyes, wallow in existential sadness, is worth all of the indulgent time the film spends on it, and Greutert helps the film successfully navigate its surprising turn towards mildly comic warmth in the middle section where Kramer thinks that he's beaten the cancer. It's an injection of earnestly light material that nevertheless needs to feel weighted in the gravity of the series - a Saw movie might be able to sell "mildly comic", but it's not selling "flippant and insincere" - and while it would feel very obtuse to call it the "best" part of the movie, it is maybe the most striking in that it is so unexpected, but carried off so smoothly. Kind of miraculous to find that this of all franchises is willing and able to make unexpected swerves ten entries in and I am surprised to find myself thinking, very much for the first time in 19 years: I do hope they get a chance to make another one.

Reviews in this series

Saw (Wan, 2004)

Saw II (Bousman, 2005)

Saw III (Bousman, 2006)

Saw IV (Bousman, 2007)

Saw V (Hackl, 2008)

Saw VI (Greutert, 2009)

Saw 3D (Greutert, 2010)

Jigsaw (Spierig Brothers, 2017)

Spiral: From the Book of Saw (Bousman, 2021)

Saw X (Greutert, 2023)

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.