Oil's well that ends well

A review requested by Dave, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

History recalls 1983's Local Hero, the third feature written and directed by Bill Forsyth, as the inspiration for a whole generation of movies about small towns in the British Isles that are full of quirky, colorful eccentrics who live life a their own idiosyncratic pace (bonus points if there's a snobby outsider who gets swept away by the charm of it all). Your Your Waking Ned. Your The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain. They dried up pretty much during the 2000s, though every now and then we still get a rotting zombie version of the form lurch into view, as recently as the gruesome Wild Mountain Thyme in 2020.

Among the people recalling it this way, we do not, importantly, find Bill Forsyth himself, who thought of Local Hero as itself looking back to an even older tradition of movies about small towns &c. He mentioned by name I Know Where I'm Going!, the 1945 film by Powell & Pressburger, as a particular model, and I think this is important: if you can situate a film as part of the long history that includes I Know Where I'm Going! or as part of the the long history that includes The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain, it is going to be much better for the film if you choose the former. And I am especially eager to perform that service for Local Hero, since I have spent almost all of the time I've known about it mentally dropping it into a bin marked "yeah, I know it has a good reputation, but if it inspired those films...", and now that I've seen it, I want very much to make sure that nobody who follows me makes the same terrible mistake. Local Hero is an extraordinary achievement, a film about Quirky Rural Eccentrics that anticipates every single trap the genre falls into and neatly pirouetting around them, giving us a film that really is the best of both worlds: it gives us the pleasant sitcom beats to appreciate and mildly chuckle at the quirkiness, while also keeping its eccentrics situated in a rudely physical, live-in reality. The phrase "magic realism minus the magic" has been floating around in my head ever since I saw it, and I know that basically just means "realism", which this isn't, but I do think it's pointing in the right direction, at least: it's a movie with the dreamy, floating quality of art that romanticises a place in a certain folk-ballad kind of register, while also seeming to be firmly and sensibly grounded in the material truth of that place.

At least initially, it feels very easy to have Local Hero pegged: in Houston, Texas, USA, there's a company called Knox Oil & Gas, which is very interested in acquiring a portion of the northwest coast of Scotland that's well-situated for building a refinery. Unfortunately, there happens to already be a picturesque small town there, a place by the name of Ferness, so Knox CEO Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster) sends one of his hottest up-and-coming negotiators to just straight-up buy the whole town: a young fellow by the name of MacIntyre (Peter Riegert), "Mac" to his buddies, largely on the grounds that it will make things go smoother if he sends a guy with a Scottish name to get the job done. Mac, descended from Hungarian Jews who changed their name upon immigrating, says nothing and accepts the job, and soon he's off to Aberdeen to meet up with a Scottish Knox employee named Danny Oldsen (Peter Capaldi), and off they go into the remote coastal wilds of the Highlands, to be charmed by the curious ways of the locals. Will they discover a tight-knit community that doesn't want to give up their ancestral homes? Will they initially try to seduce that community with their slick cosmopolitan ways, only to eventually fall in love with the place?

Not remotely. One of the biggest blindsides that Local Hero lands on the viewer is that Mac and Oldsen encounter virtually no resistance or even reluctance in signing up the whole town. The locals are, in fact, thrilled about the enormous windfall coming their way, especially bed-and-breakfast owner / the town's only accountant, Gordon Urquhart (Dennis Lawson), who mostly serves as the representative of the large community to the men from the oil company. Eventually, the horrible discovery comes through that the actual beach itself, the most crucial plot of land for the whole project, is entirely owned by one exceptionally quirky and overwhelmingly eccentric local, Ben Knox (Fulton Mackay), and he simply doesn't give any shit about money at all but does really love his beach, but that complication doesn't remotely fuel the film's plot; it doesn't even crop up until fairly deep into the film's second half.

This leaves the question, so what is actually going on in the first half of Local Hero, and my somewhat dazzled answer, having seen and loved the film, is "I don't actually know". That's another one of the... "blindsides" is the exact wrong word. That implies something shocking and abrupt, and the whole point of Forsyth's script is to be glancing and gentle. But it's so extremely gentle that it becomes shocking, in a fashion. Once the film has set its parts in motion, it proceeds to basically just shrug and say, "well, this is going to happen whether we're watching it or not", and wander off to let the boring part of the story (negotiating land usage rights) happen offscreen, while the interesting part of the story (people going about their lives) gets our full attention. The one thing about Local Hero that mostly fits the Standard Version of the story is that Mac does in fact fall in love with Ferness, and begins to feel sad that the crushing march of industry, as embodied by himself, is going to away all of the beauty and local color. But even Mac's arc doesn't go the way it's "supposed to". He's not some slick city asshole when we meet him, obsessed with modern life but without a soul. As far as we can tell, his life is very nice, and it will be very pleasant for him to return to it. People like him. He's in a stable relationship. Honestly, we don't really get to learn much about Mac: both the writing and Riegert's performance treat him more as an objective in the narrative than a subject. We're more watching the movie by peering over his shoulder than by looking through his eyes. And so there's nothing big and emotionally or spiritually dramatic about his visit, some complete rewiring of his personality, since we don't really have a great sense of what that personality is. He just really likes it here. And that is both the beauty of Local Hero, and the thing that ultimately makes it sort of weirdly sad: it's about finding that you really like something, it makes you pretty happy, and there's nothing really to be done with that. Ultimately, you're still a Hungarian-American named Mac, not a Scot named MacIntyre, and this isn't your place. Local Hero's final scenes are a remarkably weird barrage of different tones that don't make sense together all blending into a perfectly harmonious mixture of happiness and melancholy. It's a completely perfect ending (incredibly, that perfection was the result of artistic compromise: Forsyth wanted a sadder ending, the producers wanted a happier ending, and they met in the middle), one that nudges the film from "pretty damn good" up to "actually great", unsettling things and finally letting use peer right into Mac's head, learning what he wants at the exact same moment he does.

Most of the 111-minute film isn't the ending, of course, and since the film isn't going to be about fighting the big bad oil company, and it isn't going to be about watching Mac's emotional journey per se, all that's left is for it to be about sitting in a small town in Scotland and hanging out while pretty much nothing happens. It is magnificent at this. There are some mild little character drama bits littered throughout, and Oldsen gets a B-plot where he keeps bumping into a marine scientist employed by Knox, Marina (Jenny Seagrove), who might in fact be a selkie (seal-humans from Celtic myth), though it's never entirely clear if Oldsen himself suspects that, or if the movie is just pitching that straight for us. Again, everything about Local Hero happens in that half-shrugging "could be a story here, but don't you think it's more fun just to sit around peacefully?" register, including its maybe-fantastical elements. Some of the comedy is more aggressively weird than the overall casual tone. Happer, for example, is a broadly satiric parody of American corporate culture as imagined by a Scot: into goofy psychoanalytic fads, obsessed with astrology (he cares much more about Mac's regular reports about the night sky than the developing refinery deal). I would, in fact, suggest that it's too broad, and the weakest part of the film is the opening sequence in Houston, when it's taking harmless potshots at wacky corporations; that Happer ends up emerging as such an oddly sensitive and humane figure is largely to do the extraordinary performance Lancaster gives that turns his bizarre behavior into childish innocence (Lancaster was extremely enthusiastic about the script, even going to the point of taking a pay cut so that the production could afford him; you can absolutely feel that in his acting). Mostly, the comedy just radiates up from the shaggy naturalism of the film: lots of moments there's a big jokey line of dialogue and it feels so organic and comfortable that it only really registers as "funny" after the fact.

Basically, the main strength of Local Hero comes from setting us in Mac's position: watching the town, finding it kind of odd at first and then finding it very nice. I don't know if the film itself comes into focus, or if it's just that I finally slid onto its wavelength, slightly after the midway point, during a big drunken bash to celebrate the money everybody is very excited to receive once the deal is finalised; but it's a scene that very much typifies all the strengths of how Forsyth writes his characters, and how he directs his actors. Even how he and editor Michael Bradsell structure things, glancing around the space to see what everybody's up to: it's not a "cut to see somebody quip" type set-up, like party scenes often are, since we're not always cutting to something; we look over, people are still doing okay, great, now let's look over here.

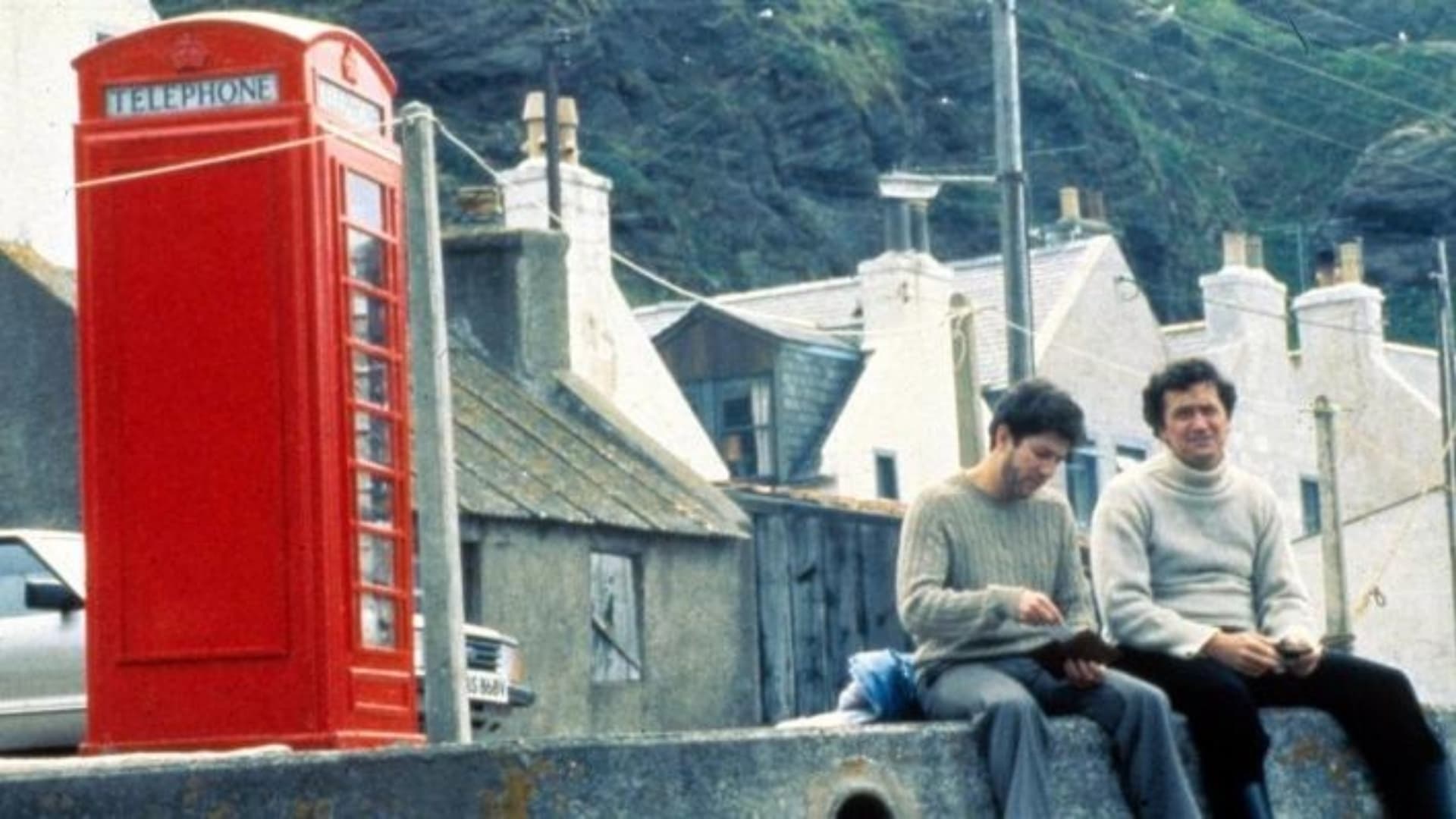

There's a similar loose realism in Chris Menges's cinematography (he's credited as "lighting cameraman"), which caught be entirely by surprise: I'm used to the later Menges, the Oscar-winning Menges, the Menges of The Mission and The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, who makes things look postcard-beautiful in an earthy, physical way. The Menges who shot Local Hero was the Menges who had shot four movies for Ken Loach. These are pretty drab images, much of the time, a little washed out (there are mostly blank-white skies), somewhat flat, never "pretty" even when they capture something striking and beautiful. This in the context of a film produced by David Puttnam, the great specialist in handsome middlebrow prestige films, and moreover the film Puttnam cashed in his clout from the Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire in order to get financing;* for it to look this scruffy and naturalistic feels practically miraculous. But it's crucial to the film's impact that it's not presenting one gorgeous Scottish landscape after another; the entire point here is that Ferness feels a bit crummy and worn-out, with routine fly-overs from a nearby military base and a bunch of irritable poor people living in it, and it's only after a great deal of time imbibing its rhythms that Mac (and the viewer) comes to really appreciate just how much richness there is in this space.

Fundamentally, the film is unromantic: that's the key to it. It takes as its subject a plot prone to romanticism, and sets it in the Scottish Highlands, one of the parts of the world that is easiest to romanticise (in fact, it was an epicenter for the actual 19th Century Romantics), and it plays it as the mixture of British kitchen-sink realism and Robert Altman that I never knew I wanted. It's generous and warm, but it's not romantic; part of the melancholic vibe that grows stronger as it goes along comes from the film seeming to pat us on the shoulder kindly and acknowledge that, even. "You really thought this was leading up to some big Romantic release, huh? Didn't even know that's what you were waiting for, probably? Well, it's not coming, so go on with your life". And yet, the feeling that lingers is how charming it's all been, and how wonderfully vivid and real the characters and town felt while we were there. It's a slow burn to get there, but this is ultimately just a phenomenal film, immediately rising to become one of my favorite British movies of the 1980s.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

*The one thing that feels obviously Puttnam-esque is that he commissioned Dire Straits guitarist Mark Knopfler to write the score, an electric-guitar fantasia on folk music motifs, and it's pretty clear that he was hoping for another Vangelis-scoring-Chariots success. He got it; the soundtrack album was a much bigger hit than the movie itself in 1983. If I am being honest, I barely even noticed the music prior to the end credits scroll. And I will continue to be honest and admit that the cue playing during the end credits is terrific.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

History recalls 1983's Local Hero, the third feature written and directed by Bill Forsyth, as the inspiration for a whole generation of movies about small towns in the British Isles that are full of quirky, colorful eccentrics who live life a their own idiosyncratic pace (bonus points if there's a snobby outsider who gets swept away by the charm of it all). Your Your Waking Ned. Your The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain. They dried up pretty much during the 2000s, though every now and then we still get a rotting zombie version of the form lurch into view, as recently as the gruesome Wild Mountain Thyme in 2020.

Among the people recalling it this way, we do not, importantly, find Bill Forsyth himself, who thought of Local Hero as itself looking back to an even older tradition of movies about small towns &c. He mentioned by name I Know Where I'm Going!, the 1945 film by Powell & Pressburger, as a particular model, and I think this is important: if you can situate a film as part of the long history that includes I Know Where I'm Going! or as part of the the long history that includes The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain, it is going to be much better for the film if you choose the former. And I am especially eager to perform that service for Local Hero, since I have spent almost all of the time I've known about it mentally dropping it into a bin marked "yeah, I know it has a good reputation, but if it inspired those films...", and now that I've seen it, I want very much to make sure that nobody who follows me makes the same terrible mistake. Local Hero is an extraordinary achievement, a film about Quirky Rural Eccentrics that anticipates every single trap the genre falls into and neatly pirouetting around them, giving us a film that really is the best of both worlds: it gives us the pleasant sitcom beats to appreciate and mildly chuckle at the quirkiness, while also keeping its eccentrics situated in a rudely physical, live-in reality. The phrase "magic realism minus the magic" has been floating around in my head ever since I saw it, and I know that basically just means "realism", which this isn't, but I do think it's pointing in the right direction, at least: it's a movie with the dreamy, floating quality of art that romanticises a place in a certain folk-ballad kind of register, while also seeming to be firmly and sensibly grounded in the material truth of that place.

At least initially, it feels very easy to have Local Hero pegged: in Houston, Texas, USA, there's a company called Knox Oil & Gas, which is very interested in acquiring a portion of the northwest coast of Scotland that's well-situated for building a refinery. Unfortunately, there happens to already be a picturesque small town there, a place by the name of Ferness, so Knox CEO Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster) sends one of his hottest up-and-coming negotiators to just straight-up buy the whole town: a young fellow by the name of MacIntyre (Peter Riegert), "Mac" to his buddies, largely on the grounds that it will make things go smoother if he sends a guy with a Scottish name to get the job done. Mac, descended from Hungarian Jews who changed their name upon immigrating, says nothing and accepts the job, and soon he's off to Aberdeen to meet up with a Scottish Knox employee named Danny Oldsen (Peter Capaldi), and off they go into the remote coastal wilds of the Highlands, to be charmed by the curious ways of the locals. Will they discover a tight-knit community that doesn't want to give up their ancestral homes? Will they initially try to seduce that community with their slick cosmopolitan ways, only to eventually fall in love with the place?

Not remotely. One of the biggest blindsides that Local Hero lands on the viewer is that Mac and Oldsen encounter virtually no resistance or even reluctance in signing up the whole town. The locals are, in fact, thrilled about the enormous windfall coming their way, especially bed-and-breakfast owner / the town's only accountant, Gordon Urquhart (Dennis Lawson), who mostly serves as the representative of the large community to the men from the oil company. Eventually, the horrible discovery comes through that the actual beach itself, the most crucial plot of land for the whole project, is entirely owned by one exceptionally quirky and overwhelmingly eccentric local, Ben Knox (Fulton Mackay), and he simply doesn't give any shit about money at all but does really love his beach, but that complication doesn't remotely fuel the film's plot; it doesn't even crop up until fairly deep into the film's second half.

This leaves the question, so what is actually going on in the first half of Local Hero, and my somewhat dazzled answer, having seen and loved the film, is "I don't actually know". That's another one of the... "blindsides" is the exact wrong word. That implies something shocking and abrupt, and the whole point of Forsyth's script is to be glancing and gentle. But it's so extremely gentle that it becomes shocking, in a fashion. Once the film has set its parts in motion, it proceeds to basically just shrug and say, "well, this is going to happen whether we're watching it or not", and wander off to let the boring part of the story (negotiating land usage rights) happen offscreen, while the interesting part of the story (people going about their lives) gets our full attention. The one thing about Local Hero that mostly fits the Standard Version of the story is that Mac does in fact fall in love with Ferness, and begins to feel sad that the crushing march of industry, as embodied by himself, is going to away all of the beauty and local color. But even Mac's arc doesn't go the way it's "supposed to". He's not some slick city asshole when we meet him, obsessed with modern life but without a soul. As far as we can tell, his life is very nice, and it will be very pleasant for him to return to it. People like him. He's in a stable relationship. Honestly, we don't really get to learn much about Mac: both the writing and Riegert's performance treat him more as an objective in the narrative than a subject. We're more watching the movie by peering over his shoulder than by looking through his eyes. And so there's nothing big and emotionally or spiritually dramatic about his visit, some complete rewiring of his personality, since we don't really have a great sense of what that personality is. He just really likes it here. And that is both the beauty of Local Hero, and the thing that ultimately makes it sort of weirdly sad: it's about finding that you really like something, it makes you pretty happy, and there's nothing really to be done with that. Ultimately, you're still a Hungarian-American named Mac, not a Scot named MacIntyre, and this isn't your place. Local Hero's final scenes are a remarkably weird barrage of different tones that don't make sense together all blending into a perfectly harmonious mixture of happiness and melancholy. It's a completely perfect ending (incredibly, that perfection was the result of artistic compromise: Forsyth wanted a sadder ending, the producers wanted a happier ending, and they met in the middle), one that nudges the film from "pretty damn good" up to "actually great", unsettling things and finally letting use peer right into Mac's head, learning what he wants at the exact same moment he does.

Most of the 111-minute film isn't the ending, of course, and since the film isn't going to be about fighting the big bad oil company, and it isn't going to be about watching Mac's emotional journey per se, all that's left is for it to be about sitting in a small town in Scotland and hanging out while pretty much nothing happens. It is magnificent at this. There are some mild little character drama bits littered throughout, and Oldsen gets a B-plot where he keeps bumping into a marine scientist employed by Knox, Marina (Jenny Seagrove), who might in fact be a selkie (seal-humans from Celtic myth), though it's never entirely clear if Oldsen himself suspects that, or if the movie is just pitching that straight for us. Again, everything about Local Hero happens in that half-shrugging "could be a story here, but don't you think it's more fun just to sit around peacefully?" register, including its maybe-fantastical elements. Some of the comedy is more aggressively weird than the overall casual tone. Happer, for example, is a broadly satiric parody of American corporate culture as imagined by a Scot: into goofy psychoanalytic fads, obsessed with astrology (he cares much more about Mac's regular reports about the night sky than the developing refinery deal). I would, in fact, suggest that it's too broad, and the weakest part of the film is the opening sequence in Houston, when it's taking harmless potshots at wacky corporations; that Happer ends up emerging as such an oddly sensitive and humane figure is largely to do the extraordinary performance Lancaster gives that turns his bizarre behavior into childish innocence (Lancaster was extremely enthusiastic about the script, even going to the point of taking a pay cut so that the production could afford him; you can absolutely feel that in his acting). Mostly, the comedy just radiates up from the shaggy naturalism of the film: lots of moments there's a big jokey line of dialogue and it feels so organic and comfortable that it only really registers as "funny" after the fact.

Basically, the main strength of Local Hero comes from setting us in Mac's position: watching the town, finding it kind of odd at first and then finding it very nice. I don't know if the film itself comes into focus, or if it's just that I finally slid onto its wavelength, slightly after the midway point, during a big drunken bash to celebrate the money everybody is very excited to receive once the deal is finalised; but it's a scene that very much typifies all the strengths of how Forsyth writes his characters, and how he directs his actors. Even how he and editor Michael Bradsell structure things, glancing around the space to see what everybody's up to: it's not a "cut to see somebody quip" type set-up, like party scenes often are, since we're not always cutting to something; we look over, people are still doing okay, great, now let's look over here.

There's a similar loose realism in Chris Menges's cinematography (he's credited as "lighting cameraman"), which caught be entirely by surprise: I'm used to the later Menges, the Oscar-winning Menges, the Menges of The Mission and The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, who makes things look postcard-beautiful in an earthy, physical way. The Menges who shot Local Hero was the Menges who had shot four movies for Ken Loach. These are pretty drab images, much of the time, a little washed out (there are mostly blank-white skies), somewhat flat, never "pretty" even when they capture something striking and beautiful. This in the context of a film produced by David Puttnam, the great specialist in handsome middlebrow prestige films, and moreover the film Puttnam cashed in his clout from the Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire in order to get financing;* for it to look this scruffy and naturalistic feels practically miraculous. But it's crucial to the film's impact that it's not presenting one gorgeous Scottish landscape after another; the entire point here is that Ferness feels a bit crummy and worn-out, with routine fly-overs from a nearby military base and a bunch of irritable poor people living in it, and it's only after a great deal of time imbibing its rhythms that Mac (and the viewer) comes to really appreciate just how much richness there is in this space.

Fundamentally, the film is unromantic: that's the key to it. It takes as its subject a plot prone to romanticism, and sets it in the Scottish Highlands, one of the parts of the world that is easiest to romanticise (in fact, it was an epicenter for the actual 19th Century Romantics), and it plays it as the mixture of British kitchen-sink realism and Robert Altman that I never knew I wanted. It's generous and warm, but it's not romantic; part of the melancholic vibe that grows stronger as it goes along comes from the film seeming to pat us on the shoulder kindly and acknowledge that, even. "You really thought this was leading up to some big Romantic release, huh? Didn't even know that's what you were waiting for, probably? Well, it's not coming, so go on with your life". And yet, the feeling that lingers is how charming it's all been, and how wonderfully vivid and real the characters and town felt while we were there. It's a slow burn to get there, but this is ultimately just a phenomenal film, immediately rising to become one of my favorite British movies of the 1980s.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

*The one thing that feels obviously Puttnam-esque is that he commissioned Dire Straits guitarist Mark Knopfler to write the score, an electric-guitar fantasia on folk music motifs, and it's pretty clear that he was hoping for another Vangelis-scoring-Chariots success. He got it; the soundtrack album was a much bigger hit than the movie itself in 1983. If I am being honest, I barely even noticed the music prior to the end credits scroll. And I will continue to be honest and admit that the cue playing during the end credits is terrific.

Categories: british cinema, comedies