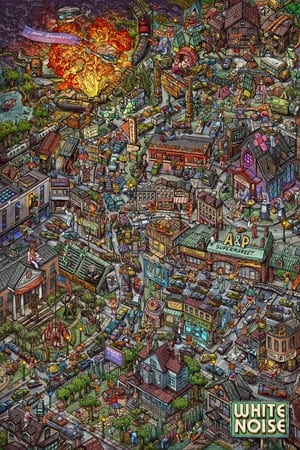

Since its 1985 publication, Don DeLillo’s most celebrated novel, White Noise, has been one of cinema’s white whales. In various superficial respects, the book has always appeared ripe for adaptation—characters are vivid; snappy dialogue abounds; there’s even a literally central catastrophe that unmistakably lends itself to visual pyrotechnics. Yet it’s taken nearly 40 years for this dream to be realized, and the reason is simple: Anyone who reads and loves White Noise—mighty hard to accomplish the former minus the latter—has to recognize, deep down in their gut, that it’s one of those exceptional, borderline magical novels that an ostensibly faithful movie version could only ruin, or at least diminish by association (in the way that we now collectively, involuntarily perceive The Bonfire of the Vanities as a Brundlefly gene-splice of Wolfe’s triumph with De Palma’s disaster). Just making the quixotic attempt means failing to show proper respect. If you genuinely admired White Noise as much you claim in various award-positioning interviews, Mr. Twice-Oscar-Nominated-Auteur Noah Baumbach, you would leave it the fuck alone.

Well, I’m glad he didn’t, because watching DeLillo’s vision take concrete form proves downright thrilling, at times bordering on miraculous. Which is not to suggest that Baumbach (who also wrote the screenplay) successfully “cracked” the book, or that everything onscreen works as intended; indeed, much of the film’s third and final section falls completely flat, necessitating an elaborate end-credits rescue mission carried out by the entire cast + LCD Soundsystem. On the whole, though, he’s pulled off something truly remarkable here, remaining slavishly faithful to the source (within the limits of a movie running two hours and change) while simultaneously fashioning something uniquely and boldly cinematic. That’s what any good literary adaptation is supposed to do, of course: find compelling visual analogues for the author’s singular prose style, a means of translating words into pictures. One sees it done with style all too rarely, though, and I honestly did not expect that the guy who directed such the-pen-is-mightier-than-the-camera pictures as Marriage Story, Frances Ha and Greenberg would summon the requisite formal chops.

One of the many challenges that Baumbach faced, and that I now face in this very paragraph, is that White Noise at once does and doesn’t boast a conventional narrative. Things definitely happen, including, as noted above, one very significant thing in particular. But much of the novel consists of free-floating philosophical and cultural observations—some spoken aloud by the characters, others merely thought by the book’s first-person narrator, Jack Gladney (played onscreen by Adam Driver, who’s about a decade too young for the role, at 39, but successfully makes it his own nonetheless). The most cursory of summaries would need to mention that Jack teaches Hitler Studies at a fictional liberal-arts college (called The-College-On-The-Hill); that his wife, Babette (Greta Gerwig), appears to be taking a prescription medication that nobody’s ever heard of; that Jack and Babette have a two-year-old son of their own plus six other kids from their respective previous marriages, three of whom currently live in the house with them; and that both parents feel profound, crippling anxiety at the prospect of their inevitable death. To a first approximation, White Noise is about the various deranged actions that human beings take in order to keep that terror at bay.

Or the actions that people took back in the ‘80s, at any rate. Among other virtues, White Noise is a period film that focuses on mindsets rather than cheap signifiers (though Gerwig’s “fanatical blond mop,” as DeLillo describes it, would not have survived long past 1990, and Baumbach isn’t averse to giving us oldsters the nostalgic clacking sound of gas pumps mechanically advancing cent by cent, back before they all switched to digital readouts). Babette’s pharmaceutical experiment is the most obvious indicator of when this story is taking place—nowadays, very few people feel any need to hide their mood stabilizers—but Jack’s provocative lectures, alongside the pop-psych musings of his colleague Murray Jay Siskind (Don Cheadle), likewise speak to a specific time in American history without feeling the need to clonk us upside the head with a Rubik’s Cube or an Atari 2600. The ways in which DeLillo’s startlingly prescient concerns remain relevant today need no explication, and therefore get none. Baumbach even has enough self-confidence in what he’s doing to omit what’s almost certainly DeLillo’s single most famous “bit”: “The Most Photographed Barn in America,” which Murray tells Jack cannot truly be seen after one has seen the signs so proclaiming it. It’s like staging Hamlet minus “To be or not to be,” except that in this case it was probably the wisest course.

Still, none of the above really gets at what unexpectedly makes White Noise play like an actual movie rather than a National Book Award winner that’s been lovingly, stiflingly embalmed. Part of it—a huge part—is that Baumbach hit upon exactly the right way to retain DeLillo’s often hilarious but decidedly mannered dialogue: He has the actors all speak their lines at once. Not constantly, but frequently, especially when the entire family’s together. (The screenplay also sometimes reassigns lines among the kids, with exchanges that were two-handed on the page becoming four-handed onscreen.) This has the initially disorienting but ultimately salutary effect of de-emphasizing each individual line’s ping-pong cleverness, so that we’re registering a volley of key phrases without attending that much to their specific source. In conjunction with the language’s incongruous formality, it creates a cacophonous white noise of its own, echoed by many scenes in which disembodied voices recite products names over supermarket loudspeakers and such. That Driver and Gerwig can handle this tricky business comes as no surprise; what’s remarkable is how beautifully all three of the older kids—Raffey Cassidy (The Killing of a Sacred Deer) as teen daughter Denise, Sam and May Nivola (spawn of Alessandro Nivola and Emily Mortimer) as eldest son Heinrich and younger daughter Steffie—manage what had to have been insanely precise timing. And that’s on top of the deadpan they have to maintain. It’s a delight.

Baumbach has always excelled at shooting scenes of people talking, though. That’s been his forte going all the way back to 1995’s Kicking and Screaming. What he’s never done before is serve up images so indelible that they’re forever burnt into your mind’s retina. DeLillo structured White Noise into three large sections, and the movie follows suit; section #2…well, actually, let me first note that Baumbach transforms one of the novel’s signature scenes—a sort of “dueling lecture” in which Murray discusses Elvis Presley’s relationship with his mother while Jack interjects details of Hitler’s maternal issues—into a magnificent setpiece, intricately choreographed both for the camera (it’s practically a dance, though some of that movement’s straight from DeLillo) and by the camera, which keeps mysteriously cutting away to an impending accident. Readers of the book will quickly recognize that this accident will cause what section #2 titles “The Airborne Toxic Event,” inspiring plentiful juvenile paranoia that Jack can deflect for only so long before the family’s forced to evacuate. What follows is some of the finest big-budget spectacle in recent memory, juggling tension and uneasy comedy in a way that’s unquestionably indebted to Spielberg but nonetheless sticks close to the film’s established brittle vibe. White Noise isn’t a film about the Airborne Toxic Event—that’s just a temporary means of reminding the characters of their mortality—but a shot of Jack pumping gas as a thick black cloud engulfs the bright yellow Shell sign visible behind him nonetheless chills the ol’ bone marrow like precious little else I’ve seen this year. Likewise, a sequence that sees Jack awaken in the middle of the night and spot someone sitting across the bedroom, silently watching the figure as it slips into bed with him. Maybe it’s Babette, maybe not; the light’s too terrifyingly dim for him (and for us) to tell.

I should perhaps acknowledge that my happy surprise isn’t universally shared. Initial reviews out of Venice were somewhat mixed, with even the most positive among them expressing reservations. Those critics aren’t wrong. Some of Baumbach’s unorthodox choices are tough to defend—I’m not sure why he felt that one otherwise amusing “car chase” should end with a slo-mo “flying vehicle” stunt, complete with cartoonish expressions of alarm visible through the windshield, that would look right at home in Smokey and the Bandit Part 3—and the film loses its way a bit during section #3, “Dylarama,” which dials back the visual invention and overlapping dialogue (and culminates in a sequence of semi-comic violence that’s frankly not the novel’s zenith, either). Ultimately, I can’t quite sell myself on believing that this is a thoroughly terrific alternate version of White Noise. But I hadn’t imagined that a pretty damn good alternate version of White Noise was even possible, so seeing one offers a frisson that I’m not inclined to ignore or dismiss. Maybe it shouldn’t have been made, but if it had to be, this was how to do it.

One of the first notable online film critics, having launched his site The Man Who Viewed Too Much in 1995, Mike D’Angelo has also written professionally for Entertainment Weekly, Time Out New York, The Village Voice, Esquire, Las Vegas Weekly, and The A.V. Club, among other publications. He’s been a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and currently blathers opinions almost daily on Patreon.