War poet

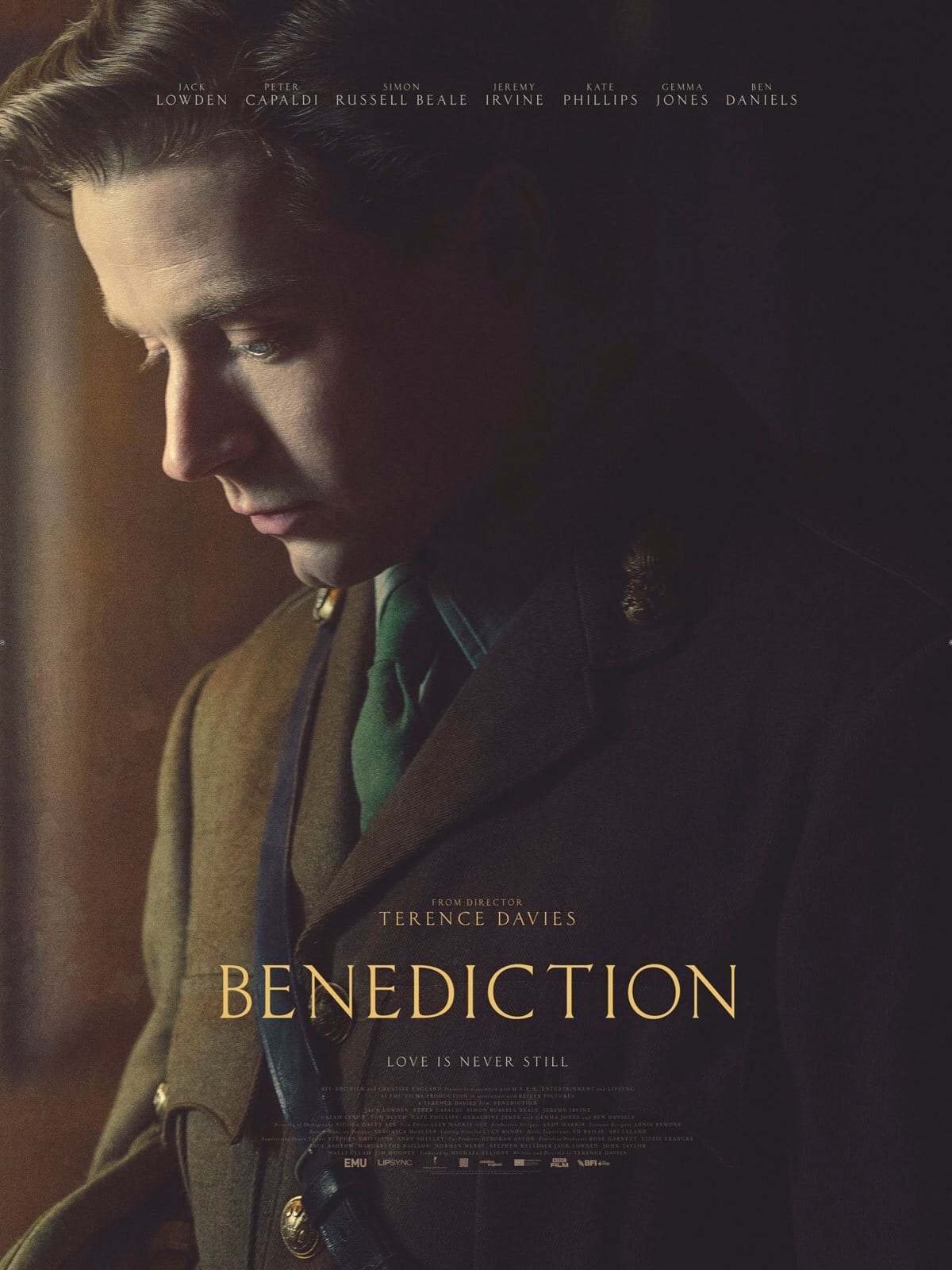

In a career spanning 45 years and nine feature-length films, the great Terence Davies, one of Great Britain's finest living directors, has made only three kinds of films: autobiographies, wordy literary adaptations, and biopics of poets. His newest feature, Benediction, is sort of all three of these things in one body. Officially speaking, it's only the last one, Davies's fictionalised and fragmented story of the life of Siegfried Sassoon, a man of wealthy background who became a ferocious anti-war activist due to his experiences on the Western Front of the First World War, and received some considerable measure of notice for his poetry about the war. So that's the "biopic" part, though it is a biopic full of ellipses and fixated much less on Sassoon's literary career than on his constantly uncomfortable emotional state, and his inability (in Davies's telling) of finding any sort of stability at any point after the war; it tells us very little about Sassoon the historical figure and mostly about Sassoon the restless man in desperate need of, well, the title is right there. Just some scrap of grace and meaning, a feeling that there's anything that can help give shape to his pain. This is frankly the only way I'd have wanted a film on this subject to be made by this particular writer-director, and even if I think you'd have to work pretty hard to argue that Benediction is top-tier Davies, this is filmmaker of uniquely penetrating power, so even his mid-level work is near the top of what anybody else is up to.

So that's one of three: it's a biopic, sort of. It's a biopic that's very heavily influenced by Davies's own history, as expressed quite clearly and ruthlessly in several of his films up to this point. So that's two of three: it is, in a sense autobiographical, in that it's the point where Davies makes the most direct reckoning with his own complicated and unhappy self-identity that he's made since his miraculous trilogy of short films, Children (1976), Madonna and Child (1980), and Death and Transfiguration (1983). In those films, and again in his abrasive 2008 memoir-documentary Of Time and the City, but not in any of his narrative features till now, Davies flung himself with desperate ambivalence and self-doubt and guilt at his own homosexuality, which combined with a conservative Catholic upbringing in childhood to make him deeply uncomfortable with his own desires, while also remaining suitably angry at the culture around him that wouldn't just let him feel his natural urges without labeling it perverse and deviant. His scripted version of Sassoon gets weighed down with quite a lot of that complicated uncertainty and discomfort with gayness, and that, in fact, is the bulk of what Benediction is focused on.

And then the third strand, the film as literary adaptation: this is as much a film about the powerful emotions expressed within Sassoon's war poems as it is about Sassoon himself, and frequently throughout the movie, Davies takes us completely out of the narrative to present impressionistic montages set to Sassoon's poems, using stock footage of the war and other images to dive into the profound pain expressed in those poems. In a sense, this is actually the most important part of all, though that only really becomes clear near the end. But it ends up being the case that Benediction is above all things the story of a man deeply and irrevocably poisoned and broken by his experience in a hopeless, needlessly violent war, which revealed to him the sheer futility of the individual human attempting to enforce some kind of order on the messiness of life. One by one, the film shows Sassoon, played in his 30s and 40s by Jack Lowden and as an old man by Peter Capaldi, trying to find something that will give him meaning and a center. First, he becomes an anti-war activist, eagerly risking a court-martial and death by execution if martyring himself means striking a blow against the depravity he has witnessed on the front. Later on there will be sex, romance, heterosexuality, Catholicism, and art itself, all things he grasps onto in the hope that they will provide an anchor for his dislocated sense of self.

It would, I suppose, constitute a spoiler to say if any of them work, but Benediction does not at any point suggest that things will end happily, and indeed, it ends on quite possibly the single most brutal, bleak note it has played across its entire 137 minutes. To a certain extent, the film doesn't even have a discernible shape until that ending, where Lowden's facial expressions communicate such a bottomless infinitude of pain and hopelessness that it suddenly allows us to see what all of the somewhat odd and dithering plot beats up to that point have been. Especially since it seems to be the case that the final scene takes place very early on in the film's chronology - it's a little slippery about that, though not nearly as much so as e.g. Distant Voices, Still Lives, where the past becomes an undifferentiated collection of moments recalled and recounted in no particular order beyond the unfathomable machinery of human memory. By comparison, Benediction almost exclusively goes in order, though the Capaldi scenes break that a bit (his first scene in particular, which fits into the narrative scheme of the film so awkwardly that I confess I'm at a complete loss to explain what the hell Davies thought he was doing with it). And the final scene breaks it even more, though here the breakage seems quite deliberate; it forces us to reconsider the entire film, which has seemed to be about the painful repression and expression of homosexual desire in an era when homosexuality was officially illegal though regarded with tolerant amusement by the sophisticated classes where Sassoon mostly operated. The final scene brutally, even cruelly confronts us with the idea that instead, this has always been about Sassoon's enormous pain at being helpless as the ghoulish machinery of war chomped through millions of Europe's young men in the 1910s, and his specific pain at having lost, to that war, the only man he ever loved, as opposed to all of the later men he'd cling to with the desperation of a drowning man clawing at a life preserver. And all the better if he could punish himself by having those men turn out to be rotten narcissists who barely try to hide their disdain for him as a person.

If that sounds largely unpleasant, it sort of is, but not unrelentingly so. There's no small amount of wit here: Davies takes great joy in reconstructing the culture of the '20s and '30s, and the English gay underground where that culture as at its most erudite and artistically sophisticated. A great deal of the film's middle is entirely about Sassoon navigating that underground largely successfully, though rarely happily, with all of the pain of war and self-loathing and guilt and whatnot having been reduced to the slowest simmer on the back burner. Truthfully, this middle is a bit flabby - 137 minutes is an indulgence for a filmmaker who has only ever made one longer feature, compared to three features under 90 minutes, and it leads to a lot of padding as we get variations on the same kind of scene: Sassoon grows so tired of maintaining an austere, sophisticated facade that he breaks down and allows himself to be vulnerable to a lover who turns out to be a caustic asshole. There are two entire characters - actor/songwriter/dramatist Ivor Novello (Jeremy Irvine) and idle nobleman Stephen Tennant (Calam Lynch) - who are used in the script basically to replicate the same exact narrative pattern, and while that repetition serves its purpose in sketching out how willfully Sassoon could make the same mistake, leading to the same despairing feelings of loneliness, it's not necessarily the most exciting thing to watch. Especially because Irvine's portrayal of Novello is so unrelentingly Bad News that it almost feels like we watch the pattern play out three different times with him even before Tennant really enters the narrative.

Granting that there is a shorter version of Benediction that I certainly love more than this, the version of Benediction we got is still pretty magnificent. Lowden's performance as Sassoon is a powerhouse, creating layers upon layers of self-protection and self-hatred. In any given moment, he might need to play the character's romantic yearing, his sexual ardor, his feelings of revulsion at those two things, and his aloof "I'm too literate and clever to actually feel feelings" demeanor that fits him like a shoe a size too small. And then add a layer when the film starts to incorporate Hester Gatty (Kate Phillips), the woman who would end up as Sassoon's wife, and Lowden then has to incorporate his hatred of this person's love for him. It's one of the best and saddest performances of the year so far, with multiple stand-out scenes (I prefer the last one, because of how much of a vicious sucker punch it is; what can I say, I like a movie that leaves me feeling sick to my stomach). Capaldi has far less to do - the older version of Sassoon is such a relatively tiny role that I'm a little surprised they bothered casting an actor so prominent, since it does somewhat make promises the film never planned to keep. But it ends up working beautifully: the film's conception of old Sassoon is that he's been so throughly emptied out emotionally by all the things that have gone wrong in his life that he has nothing left but a hard nut of bitterness, sometimes well hidden and sometimes left out in the open with terrifying intensity. And there might not be a better actor in the British Isles right now for pouring ice cold fury into a line reading like Capaldi, whose sheer inhuman anger is so pronounced in some scene that one almost stops caring that he's not doing much of anything to hide his incredibly noticeable Scottish accent.

Above and beyond its estimable qualities as a psychological drama, Benediction benefits from being directed by one of the best living chroniclers of the shimmering complexity of memory and time passing. Again, we're not talking Peak Davies, nor even are we all that close to it, but the film's techniques for erasing our sense of time and context are superb. The film is always in the present, even when it's explicitly flashing back (this is in part accomplished by two separate in-camera morphs between young and old versions of characters; it doesn't work well either time, just like it didn't really work in Davies's last film, the Emily Dickinson biopic A Quiet Passion), but it's also in a constantly hazy subjective state where the present feels untethered and uncertain. The biggest trick by which the filmmakers accomplish this is through Alex Mackie's shocking editing: this is breaking rules all over the place, and yet it never feels like a single edit or dissolve - and there are a ton of dissolves, one of the rules being broken - has been placed incorrectly. Every mismatched eyeline purposefully leaves us reeling and uncomfortable. Whenever a dissolve placed into the middle of a continuous scene throws us out of our sense of time passing smoothly, it always feels like we have just learned something about Sassoon's discomfort in every waking moment. It's hard not to feel like this is at least one step away from "a major film", but it is unmistakably made by a major filmmaker working with a gifted crew, and even in its imperfections, Benediction is, and I suspect will remain, one of the most formidable things I have seen in 2022.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

So that's one of three: it's a biopic, sort of. It's a biopic that's very heavily influenced by Davies's own history, as expressed quite clearly and ruthlessly in several of his films up to this point. So that's two of three: it is, in a sense autobiographical, in that it's the point where Davies makes the most direct reckoning with his own complicated and unhappy self-identity that he's made since his miraculous trilogy of short films, Children (1976), Madonna and Child (1980), and Death and Transfiguration (1983). In those films, and again in his abrasive 2008 memoir-documentary Of Time and the City, but not in any of his narrative features till now, Davies flung himself with desperate ambivalence and self-doubt and guilt at his own homosexuality, which combined with a conservative Catholic upbringing in childhood to make him deeply uncomfortable with his own desires, while also remaining suitably angry at the culture around him that wouldn't just let him feel his natural urges without labeling it perverse and deviant. His scripted version of Sassoon gets weighed down with quite a lot of that complicated uncertainty and discomfort with gayness, and that, in fact, is the bulk of what Benediction is focused on.

And then the third strand, the film as literary adaptation: this is as much a film about the powerful emotions expressed within Sassoon's war poems as it is about Sassoon himself, and frequently throughout the movie, Davies takes us completely out of the narrative to present impressionistic montages set to Sassoon's poems, using stock footage of the war and other images to dive into the profound pain expressed in those poems. In a sense, this is actually the most important part of all, though that only really becomes clear near the end. But it ends up being the case that Benediction is above all things the story of a man deeply and irrevocably poisoned and broken by his experience in a hopeless, needlessly violent war, which revealed to him the sheer futility of the individual human attempting to enforce some kind of order on the messiness of life. One by one, the film shows Sassoon, played in his 30s and 40s by Jack Lowden and as an old man by Peter Capaldi, trying to find something that will give him meaning and a center. First, he becomes an anti-war activist, eagerly risking a court-martial and death by execution if martyring himself means striking a blow against the depravity he has witnessed on the front. Later on there will be sex, romance, heterosexuality, Catholicism, and art itself, all things he grasps onto in the hope that they will provide an anchor for his dislocated sense of self.

It would, I suppose, constitute a spoiler to say if any of them work, but Benediction does not at any point suggest that things will end happily, and indeed, it ends on quite possibly the single most brutal, bleak note it has played across its entire 137 minutes. To a certain extent, the film doesn't even have a discernible shape until that ending, where Lowden's facial expressions communicate such a bottomless infinitude of pain and hopelessness that it suddenly allows us to see what all of the somewhat odd and dithering plot beats up to that point have been. Especially since it seems to be the case that the final scene takes place very early on in the film's chronology - it's a little slippery about that, though not nearly as much so as e.g. Distant Voices, Still Lives, where the past becomes an undifferentiated collection of moments recalled and recounted in no particular order beyond the unfathomable machinery of human memory. By comparison, Benediction almost exclusively goes in order, though the Capaldi scenes break that a bit (his first scene in particular, which fits into the narrative scheme of the film so awkwardly that I confess I'm at a complete loss to explain what the hell Davies thought he was doing with it). And the final scene breaks it even more, though here the breakage seems quite deliberate; it forces us to reconsider the entire film, which has seemed to be about the painful repression and expression of homosexual desire in an era when homosexuality was officially illegal though regarded with tolerant amusement by the sophisticated classes where Sassoon mostly operated. The final scene brutally, even cruelly confronts us with the idea that instead, this has always been about Sassoon's enormous pain at being helpless as the ghoulish machinery of war chomped through millions of Europe's young men in the 1910s, and his specific pain at having lost, to that war, the only man he ever loved, as opposed to all of the later men he'd cling to with the desperation of a drowning man clawing at a life preserver. And all the better if he could punish himself by having those men turn out to be rotten narcissists who barely try to hide their disdain for him as a person.

If that sounds largely unpleasant, it sort of is, but not unrelentingly so. There's no small amount of wit here: Davies takes great joy in reconstructing the culture of the '20s and '30s, and the English gay underground where that culture as at its most erudite and artistically sophisticated. A great deal of the film's middle is entirely about Sassoon navigating that underground largely successfully, though rarely happily, with all of the pain of war and self-loathing and guilt and whatnot having been reduced to the slowest simmer on the back burner. Truthfully, this middle is a bit flabby - 137 minutes is an indulgence for a filmmaker who has only ever made one longer feature, compared to three features under 90 minutes, and it leads to a lot of padding as we get variations on the same kind of scene: Sassoon grows so tired of maintaining an austere, sophisticated facade that he breaks down and allows himself to be vulnerable to a lover who turns out to be a caustic asshole. There are two entire characters - actor/songwriter/dramatist Ivor Novello (Jeremy Irvine) and idle nobleman Stephen Tennant (Calam Lynch) - who are used in the script basically to replicate the same exact narrative pattern, and while that repetition serves its purpose in sketching out how willfully Sassoon could make the same mistake, leading to the same despairing feelings of loneliness, it's not necessarily the most exciting thing to watch. Especially because Irvine's portrayal of Novello is so unrelentingly Bad News that it almost feels like we watch the pattern play out three different times with him even before Tennant really enters the narrative.

Granting that there is a shorter version of Benediction that I certainly love more than this, the version of Benediction we got is still pretty magnificent. Lowden's performance as Sassoon is a powerhouse, creating layers upon layers of self-protection and self-hatred. In any given moment, he might need to play the character's romantic yearing, his sexual ardor, his feelings of revulsion at those two things, and his aloof "I'm too literate and clever to actually feel feelings" demeanor that fits him like a shoe a size too small. And then add a layer when the film starts to incorporate Hester Gatty (Kate Phillips), the woman who would end up as Sassoon's wife, and Lowden then has to incorporate his hatred of this person's love for him. It's one of the best and saddest performances of the year so far, with multiple stand-out scenes (I prefer the last one, because of how much of a vicious sucker punch it is; what can I say, I like a movie that leaves me feeling sick to my stomach). Capaldi has far less to do - the older version of Sassoon is such a relatively tiny role that I'm a little surprised they bothered casting an actor so prominent, since it does somewhat make promises the film never planned to keep. But it ends up working beautifully: the film's conception of old Sassoon is that he's been so throughly emptied out emotionally by all the things that have gone wrong in his life that he has nothing left but a hard nut of bitterness, sometimes well hidden and sometimes left out in the open with terrifying intensity. And there might not be a better actor in the British Isles right now for pouring ice cold fury into a line reading like Capaldi, whose sheer inhuman anger is so pronounced in some scene that one almost stops caring that he's not doing much of anything to hide his incredibly noticeable Scottish accent.

Above and beyond its estimable qualities as a psychological drama, Benediction benefits from being directed by one of the best living chroniclers of the shimmering complexity of memory and time passing. Again, we're not talking Peak Davies, nor even are we all that close to it, but the film's techniques for erasing our sense of time and context are superb. The film is always in the present, even when it's explicitly flashing back (this is in part accomplished by two separate in-camera morphs between young and old versions of characters; it doesn't work well either time, just like it didn't really work in Davies's last film, the Emily Dickinson biopic A Quiet Passion), but it's also in a constantly hazy subjective state where the present feels untethered and uncertain. The biggest trick by which the filmmakers accomplish this is through Alex Mackie's shocking editing: this is breaking rules all over the place, and yet it never feels like a single edit or dissolve - and there are a ton of dissolves, one of the rules being broken - has been placed incorrectly. Every mismatched eyeline purposefully leaves us reeling and uncomfortable. Whenever a dissolve placed into the middle of a continuous scene throws us out of our sense of time passing smoothly, it always feels like we have just learned something about Sassoon's discomfort in every waking moment. It's hard not to feel like this is at least one step away from "a major film", but it is unmistakably made by a major filmmaker working with a gifted crew, and even in its imperfections, Benediction is, and I suspect will remain, one of the most formidable things I have seen in 2022.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Categories: british cinema, love stories, the dread biopic, top 10, war pictures