I've met worse

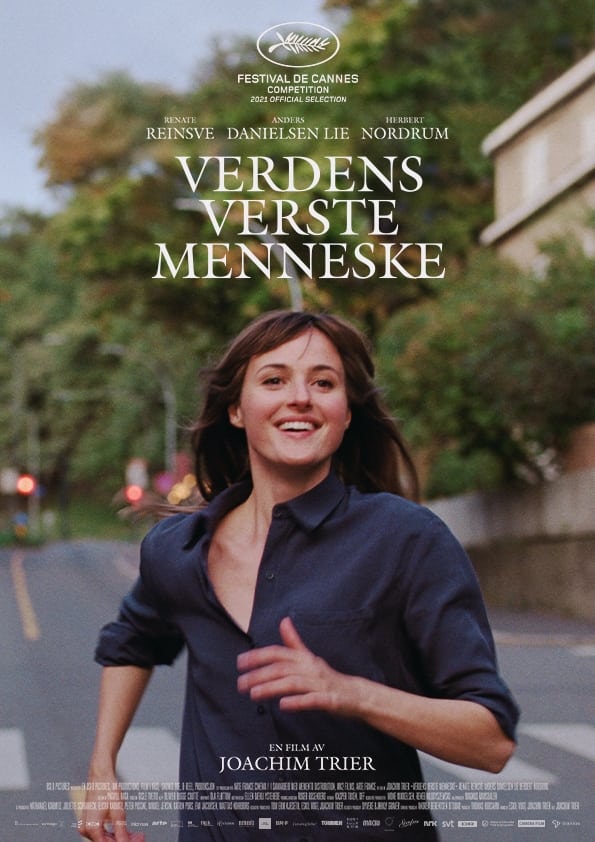

The Worst Person in the World, according to the film of that title, is a certain young woman living in Oslo, named Julie (Renate Reinsve). We spend a few years with her, from her late 20s to her early 30s, and one important thing is learned in those years, twice: first, we learn that Julie is by no means the worst person in the world, and of course that comes as very little surprise, so we learn it awfully quickly. Then, Julie herself learns that she is not the worst person in the world, and that is something that takes much more time, all of those years and much of the film's 128 minutes (which are unusually well-paced - the film is broken into 14 distinct pieces, which undoubtedly helps). And, of course, the joke of it is that the title is a bit of breathless hyperbole, but it's breathless hyperbole that already has begun to ease us into the mood of the film even before it starts. For it's a title reflective of the way that people who haven't yet gotten a handle on adulthood tend to think that everything is the absolute most important, and reflective of well as the way that those same people magnify their own strengths and weaknesses all out of proportion to the extremely modest importance any one human personality has on the world writ large. In short, the title is about how your 20s are about everything being a catastrophe, and leaving your 20s is about realising that actually none of that stuff was catastrophic at all, and that here you are in your 30s and life is still just plugging along.

(Also, the Norwegian title translates literally as The World's Worst Person. Allowing for the differences between Norwegian and English grammar, as well as idiomatic language, The Worst Person in the World is a perfectly accurate translation, but I have to admit that I much prefer the cadence of the literal version).

The film is the fifth by director Joachim Trier, and it represents a very gratifying return to his roots. I have no problem with Trier's last two films, 2015's Louder Than Bombs and 2017's Thelma - indeed, I think the former is extremely good verging on great, and the latter, while obviously the director's weakest work to date, still has a great deal that I admire - but they both lack the splendid intimacy and acute perception of his first two, 2006's Reprise and 2011's Oslo, 31 August. It's surely reductive to say that this is solely because they're not psychological realist stories about untethered young adults stumbling around Oslo without knowing where they're going; but it's hard not to suppose that's part of it. Especially since that's exactly what Worst Person is about, and it is just a remarkable, rich, lively, and wise thing.

We have here less of a plot than a general thrust: Julie is introduced to us in the form of a whirlwind of dry, ironic narration attached to a series of moments, too big to call it a montage and too small to call them individual scenes, and in this introduction we find a woman who has no idea what she likes - not that she doesn't know what she wants to do, though of course that's part of it. She is, in this prologue, an amorphous collection of personality tics that haven't yet resolved into a person, making the jump from medical student to psychology student to photography student so quickly that it's not entirely clear yet that the film has begun by the time she cycles through them. Trier and his irreplaceable co-writer Eskil Vogt can't keep up that kind of constant reinvention and probably never wanted to, so it's no real surprise when the montage ends and Worst Person actually starts to behave like a movie, but it's still one that keeps shifting around abruptly. It announces at the start that it will take place in the form of 12 chapters with a prologue and an epilogue, and every one of those chapters takes place at some chronological and emotional remove from the next; the result is not so much that we see Julie's life as an evolution but as a series of revolutions, as if she's always a slightly different person when we catch up with her next. It's kind of perfect, a narrative structure that captures the feeling one gets when, from the vantage point of having reached a kind of equilibrium in life, one looks back five or ten or fifteen years and is simply gobsmacked to wonder, "who was that person I used to be?" Julie never exactly has that moment, but she doesn't need to; the elliptical scene transitions do it for her.

All this constant shifting, re-evaluating, finding new aspects of herself, and the rest, makes Julie an almost impossible character to pin down, and it is nothing shy of a flat-out miracle that Reinsve is able to make the character feel so unified across all 14 fragments of Worst Person's narrative. Trier has constructed the film such that anything less than one of the very best performances of the year, and the whole movie would fall apart, so it's good that Reinsve provided just such a thing: she selects a few key things that she can repeat throughout the movie - facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice - so that even as Julie makes different choices and reacts to things in different ways, we can feel the continuity across scenes. Meanwhile, she also commits to those choices, giving us plenty of room to see how the character might have ended up on the various wrong tracks, or at least not-obviously-right tracks, that she stumbles across throughout the movie.

The bulk of The Worst Person in the World is about Julie's clumsy handling of her love life, first falling in with the pleasant but distinctly bro-ey Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), who is on top of that painfully too old for her; this comes to an end when she starts sleeping with the unhappily married Eivind (Herbert Nordrum). It's never melodramatic in the least, and stands respectively back from Julie as she makes choices that are probably not very good choices at all, without judging her or trying to cast this as a tragedy in the waiting. This is a series of snapshots of human behavior, not a diagnosis of who Julie is; and some extraordinary snapshots they are. Trier lets all of the narrative beats find their own tone, so the film is sometimes hilarious and sometimes very sad, and near the end, it is warm and uplifting despite resolving on some plot beats that you would think, on paper, might be at least melancholic if not altogether downbeat. Mostly, it's just interestingly human: Reinsve and Danielsen Lie are inhabiting their roles with all the complex internal contradictions of actual people (Nordrum is fine, but his role is simply not as layered), and no matter what we're feeling at any given moment, it feels honest and grounded.

Given the film's curiousity, and its generously sprawling approach to capturing slices of Julie's life, it can't help but be scattered and uneven. There are moments of piercing beauty (my favorite of which would constitute an forgivable spoiler - it involves the camera making some unexpectedly sharp and sudden movements in connection with Danielsen Lie's body movements); there are cute little goofy anecdotes, like when Julie runs down the street while the world seems frozen around her, a bit stylistic gesture that's kind of corny and trite. But also sometimes young adults have experiences so moving and important to them that the fact that they're slightly boring clichés to the rest of us is immaterial, and this is that kind of moment, and it's very nice. Sometimes, Trier completely overplays his hand, and just plain fucks up: there's a hallucinogenic scene here that I would readily declare the worst moment in an otherwise great film from 2021. But that's kind of the film's vibe: you make some dumb mistakes sometimes, and move on from them. I would say that these sorts of things are why the film is better as a collection of moments than as a whole object, but that's certainly missing the point: the film is a collection of moments, little crystalline bits of time more important in and of themselves than because of what they add up to. And they end up adding up to something in the end, anyways. The Worst Person in the World is imperfect, but it has so many good points that I couldn't help but love it a little bit - very much the way the film feels about its character, in fact.

(Also, the Norwegian title translates literally as The World's Worst Person. Allowing for the differences between Norwegian and English grammar, as well as idiomatic language, The Worst Person in the World is a perfectly accurate translation, but I have to admit that I much prefer the cadence of the literal version).

The film is the fifth by director Joachim Trier, and it represents a very gratifying return to his roots. I have no problem with Trier's last two films, 2015's Louder Than Bombs and 2017's Thelma - indeed, I think the former is extremely good verging on great, and the latter, while obviously the director's weakest work to date, still has a great deal that I admire - but they both lack the splendid intimacy and acute perception of his first two, 2006's Reprise and 2011's Oslo, 31 August. It's surely reductive to say that this is solely because they're not psychological realist stories about untethered young adults stumbling around Oslo without knowing where they're going; but it's hard not to suppose that's part of it. Especially since that's exactly what Worst Person is about, and it is just a remarkable, rich, lively, and wise thing.

We have here less of a plot than a general thrust: Julie is introduced to us in the form of a whirlwind of dry, ironic narration attached to a series of moments, too big to call it a montage and too small to call them individual scenes, and in this introduction we find a woman who has no idea what she likes - not that she doesn't know what she wants to do, though of course that's part of it. She is, in this prologue, an amorphous collection of personality tics that haven't yet resolved into a person, making the jump from medical student to psychology student to photography student so quickly that it's not entirely clear yet that the film has begun by the time she cycles through them. Trier and his irreplaceable co-writer Eskil Vogt can't keep up that kind of constant reinvention and probably never wanted to, so it's no real surprise when the montage ends and Worst Person actually starts to behave like a movie, but it's still one that keeps shifting around abruptly. It announces at the start that it will take place in the form of 12 chapters with a prologue and an epilogue, and every one of those chapters takes place at some chronological and emotional remove from the next; the result is not so much that we see Julie's life as an evolution but as a series of revolutions, as if she's always a slightly different person when we catch up with her next. It's kind of perfect, a narrative structure that captures the feeling one gets when, from the vantage point of having reached a kind of equilibrium in life, one looks back five or ten or fifteen years and is simply gobsmacked to wonder, "who was that person I used to be?" Julie never exactly has that moment, but she doesn't need to; the elliptical scene transitions do it for her.

All this constant shifting, re-evaluating, finding new aspects of herself, and the rest, makes Julie an almost impossible character to pin down, and it is nothing shy of a flat-out miracle that Reinsve is able to make the character feel so unified across all 14 fragments of Worst Person's narrative. Trier has constructed the film such that anything less than one of the very best performances of the year, and the whole movie would fall apart, so it's good that Reinsve provided just such a thing: she selects a few key things that she can repeat throughout the movie - facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice - so that even as Julie makes different choices and reacts to things in different ways, we can feel the continuity across scenes. Meanwhile, she also commits to those choices, giving us plenty of room to see how the character might have ended up on the various wrong tracks, or at least not-obviously-right tracks, that she stumbles across throughout the movie.

The bulk of The Worst Person in the World is about Julie's clumsy handling of her love life, first falling in with the pleasant but distinctly bro-ey Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), who is on top of that painfully too old for her; this comes to an end when she starts sleeping with the unhappily married Eivind (Herbert Nordrum). It's never melodramatic in the least, and stands respectively back from Julie as she makes choices that are probably not very good choices at all, without judging her or trying to cast this as a tragedy in the waiting. This is a series of snapshots of human behavior, not a diagnosis of who Julie is; and some extraordinary snapshots they are. Trier lets all of the narrative beats find their own tone, so the film is sometimes hilarious and sometimes very sad, and near the end, it is warm and uplifting despite resolving on some plot beats that you would think, on paper, might be at least melancholic if not altogether downbeat. Mostly, it's just interestingly human: Reinsve and Danielsen Lie are inhabiting their roles with all the complex internal contradictions of actual people (Nordrum is fine, but his role is simply not as layered), and no matter what we're feeling at any given moment, it feels honest and grounded.

Given the film's curiousity, and its generously sprawling approach to capturing slices of Julie's life, it can't help but be scattered and uneven. There are moments of piercing beauty (my favorite of which would constitute an forgivable spoiler - it involves the camera making some unexpectedly sharp and sudden movements in connection with Danielsen Lie's body movements); there are cute little goofy anecdotes, like when Julie runs down the street while the world seems frozen around her, a bit stylistic gesture that's kind of corny and trite. But also sometimes young adults have experiences so moving and important to them that the fact that they're slightly boring clichés to the rest of us is immaterial, and this is that kind of moment, and it's very nice. Sometimes, Trier completely overplays his hand, and just plain fucks up: there's a hallucinogenic scene here that I would readily declare the worst moment in an otherwise great film from 2021. But that's kind of the film's vibe: you make some dumb mistakes sometimes, and move on from them. I would say that these sorts of things are why the film is better as a collection of moments than as a whole object, but that's certainly missing the point: the film is a collection of moments, little crystalline bits of time more important in and of themselves than because of what they add up to. And they end up adding up to something in the end, anyways. The Worst Person in the World is imperfect, but it has so many good points that I couldn't help but love it a little bit - very much the way the film feels about its character, in fact.

Categories: coming-of-age, love stories, scandinavian cinema