A man and a woman

The best thing ever made for television, anywhere in the world, is the 10-part miniseries Dekalog from 1988 - I think this is maybe even objectively true. The second-best thing ever made for television, anywhere in the world, now that's where we can start to have arguments. For me, I think it's a dead heat between two miniseries that were both made by Ingmar Bergman, on either side of the penultimate phase of his career (we might even call it "the television phase", given how many of his "film" projects were actually made for TV from 1973 onward). The latter of these is Fanny and Alexander, which aired as a four-part miniseries in 1983, and we will hear its claim to medium-defining masterpiece status elsewhere. For right now, we're going to park our butts in our living rooms in 1973, where on six consecutive Wednesday evenings in April and May, audiences were first treated to a handful of Scenes from a Marriage.

Before diving into the series itself, I want to stress the miracle of this series' reception. It was a monstrous hit - 3.5 million people watched the highest-rated fifth episode on Swedish television, more than half of the adult population of the country. The series is widely regarded as having triggered a substantial increase in the country's divorce rate. We have, in other words, the clearest example of something I tried to suggest in connection with Cries and Whispers, which is that Bergman, for all his clout in the art cinema world, actually had the tastes and storytelling instincts of a popular entertainer - he just created popular entertainment on crushing, miserable subjects that involved much gloomy philosophy. But in making his first TV series, he wanted to do right by TV, making something watchable on a mass level.

He achieved this; the viewership numbers show that. Anecdotally, I would, if I could, share a personal story - or a personal story once removed. Many years ago, when I was a wee cinephile, I saw the series for the first time and was bowled over every which way, and I wanted so badly to share it with people. Among these people were my parents, who had been reluctant to watch any Bergman films, owing to his daunting reputation as a miserabilist; I lent them the discs, pointing out that it was only a 50-minute commitment on six consecutive nights, which is certainly how I watched it, and how I recommended they watch it - the pileup of intense, bleak emotions would be almost too much to imagine otherwise. So on a Saturday afternoon, my mother called to tell me they were about to start watching it, wish them luck, the whole thing. And I went about my own day. Five hours later, my mother called again - they had binged all six episodes without a single pause.

I love my parents, but they're not the kind of people who get swept away in a movie or TV show. So for them to be that transfixed by Scenes from a Marriage, enough to let its unblinking view of humans failing to forge emotional bonds crash over them for five uninterrupted hours (something I have, to this day, never had the bravery to try), I think this says something about the unique power of this series. It is unusually watchable for Bergman, to be sure, but not because it is easier to take; on the contrary, my feeling the end of every episode (and part of the reason why I can't watch two of them in a row, let alone six), is that the show has punched through my gut and pulled out my spine. The last beat of every episode is a motherfucker, slicing through the languid rhythms of the 48 preceding minutes in a jarring, disruptive, even mean way, and it makes the experience of watching the series feel like pumping the brakes on a fast car over and over.

But as emotionally draining as it to watch an acrimonious divorce happen in what feels like real time, especially one that has all of those nasty little sucker punches coiled up and ready, Scenes from a Marriage is a gripping, exciting watch. It is television, after all, and Bergman's top priority was crafting something that would be engaging enough not just for the 50 minutes of each episode, but to make you want to come back next week and endure all of this with his protagonists. This is certainly what makes it different from Fanny and Alexander, and arguably what makes it different from Dekalog: Scenes from a Marriage never plays at being a cinematic work that has, for reasons of convenience, found a home on the small screen. It was designed to be seen in that medium, which is part of the reason why I find the existence of a 169-minute reduction of the series that was released in theaters in 1974 (internationally, I believe, though it's almost invariably referred to as the "U.S. cut") so baffling. Okay, not "baffling" - it's for obvious commercial reasons. "Infuriating". Not just because losing nearly two hours of content severely hollows out the material; not just because the perfect shape of the episodes, each telling one complete anecdote about a major event in the life of a married couple, and their ironically bright little epilogues (Bergman narrating the credits over a snatch of Baroque music and beautiful landscape footage from the island of Fårö, where the series was shot), go missing in the onrush of the feature. It's because this feels like something meant to be watched in your living room; we invite this story and these characters into our domestic space as they bang around their own domestic space. It is one of the most deeply intimate works of filmed media I have ever seen, and that feeling of close connection, like the television isn't a window into another world so much as a mirror on the families watching it, is a crucial part of the reason why.

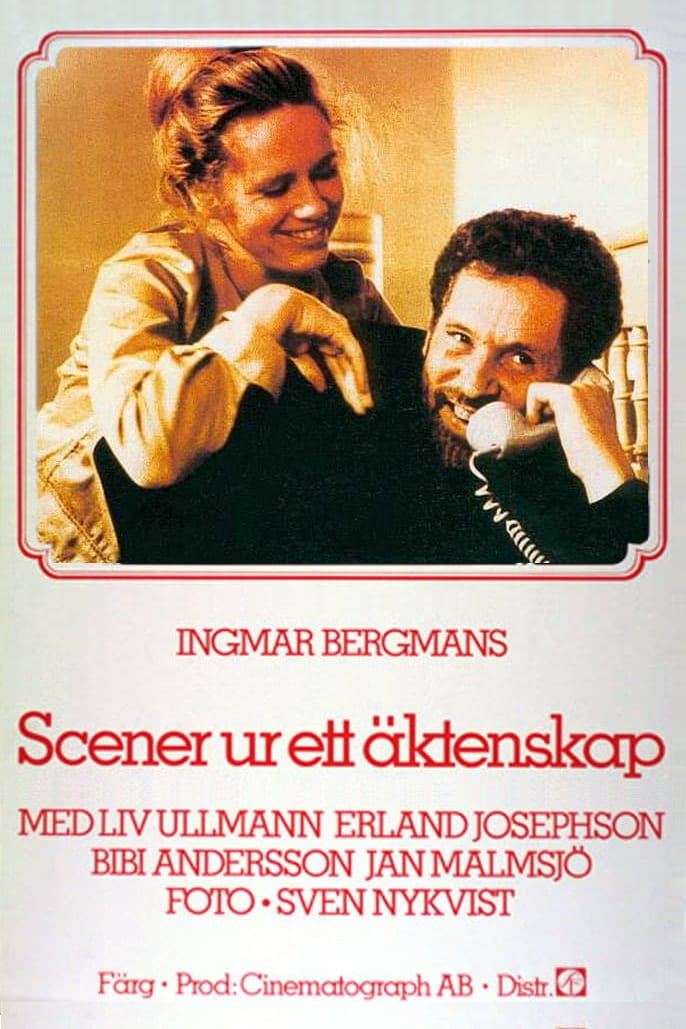

That sure is a lot of words to have not even clearly indicated what Scenes from a Marriage is. In short, Johan (Erland Josephson) and Marianne (Liv Ullmann) have been married for ten years when we meet them, giving an interview to a journalist (Anita Wall) from a lifestyle magazine, an old acquaintance of Marianne's. The purpose of the magazine story - much like the purpose of the miniseries - seems to be to capture something of the essence of an aggressively normal bourgeois marriage. Certainly nothing about either of these people seems exceptional, and it is not the argument of Scenes from a Marriage that they are. This is an argument that unexceptional people can still be rich, unbearably rich subjects for psychological inquiry. Anyway, we learn during the interview that Johan, at 42, is a cocksure blowhard, and that Marianne, at 35, has absolutely no sense of self that isn't defined in terms of her role in a family, and they are perfectly happy with each other, no need for self-reflection. And this persists even after they celebrate the publication of the magazine article by hosting another couple for dinner, only to have that couple - Katarina (Bibi Andersson, stunning and potent in her brief final appearance in a Bergman film) and Peter (Jan Malmsjö) get into a deeply vicious and cutting argument right in front of them.

Over the course of the next four episodes, spanning three years, we will learn, as will the characters, that the marriage is held together by inertia rather than truth, that Johan feels bored enough to run away with another woman, that being forced to fend for herself is good for Marianne's emotional well-being, that Johan's bluster is a mask for deep, uncontrollable insecurity. And then the sixth episode skips ahead seven years, to what would have been the couple's twentieth wedding anniversary, to find that they are both wiser, and maybe not even sadder, and that it only took a little thing like a rancorous divorce for them to realise how much they valued one another's presence in their lives.

All of this is small and pointedly minimalist: three of the episodes (3, 4, and 5, to be exact) contain no other actors than Ullmann and Josephson, and one of them (5) is in real-time. It's the closest to theater that any of Bergman's films ever got, and accordingly, it was later turned into a stage production, though I doubt very much that was to its benefit; just because the series strips the chamber drama down to its sparest essence (this was, in effect, the end of Bergman's dalliance with cinematic chamber dramas, the director having perhaps realised that this perfected the form) does not mean that it's not using its visuals in a tremendously careful way. For in addition to being Bergman's ultimate character drama, it his ultimate experiment in close-ups, and I don't mind saying that Scenes from a Marriage is where I first realised that nothing, but nothing, was a more profound cinematic subject than the human face, boxed into the frame with no room for us to look at anything but the smallest grace notes of expression and performance.

The cinematic structure of Scenes from a Marriage is, in fact, at the level of shot scales: while the close-ups dominate my brain so fully that I tend to remember the series as five uninterrupted hours of them, Bergman and editor Siv Lundgren hang onto them very judiciously (I would go so far as to call this the best-edited project of the director's career). The show's default state is epic-length takes of Ullmann and Josephson having different kinds of arguments - sometimes sharp and hostile ones, sometimes confused and hurt ones, most often just conversations where neither participant quite realises that that they're using the same words to mean different things and so a whole lot of air is spend circling around simple ideas. Because there are so many long takes, every single cut carries an enormous amount of meaning, exploding like a small bomb. In the first episode, "Innocence and Panic", Marianne follows Johan's smooth, perfectly-formed self-narrative with a meandering, repetitive attempt to describe her life and her feelings, straining like an idiot to form a compelling thought, with Ullmann exuding a look of nervous confusion. In the middle of this, the film cuts to the interviewer confidently asking a new question, and the sudden throttling-back of pressure is palpable, like not just the interviewer but the film itself has taken pity on Marianne in her low-grade panic. That's the first really noticeable, powerful cut, but there are plenty to come: places where the show quietly but insistently informs us that watching someone listening will be more important than watching someone talking, controlling how we perceive conversations by controlling who is visually "winning". Changes in shot scale work within that framework to mark out intensification in the argument, sometimes serving as our only real indication that such intensification has taken place, until it erupts into open conflict, perhaps minutes later.

Also, sometimes, the editing is just there to focus our attention like a telescope on Ullmann's performance. Scenes from a Marriage contains, in Erland Josephson's performance, a tremendous piece of acting, moving from unreflective egotism to reflective, guilty egotism, to pathetic, loathsome desperation, finally ending a place of worn-out warmth and peace in the finale scene; and despite this, he is indisputably the less-interesting, weaker actor. Ullmann's work is medium-defining; I'm not even completely sure it's my favorite performance she gave for Bergman, but I'd also be open to the argument that it's the best piece of screen acting in history. Scenes from a Marriage was based in part on Bergman and Ullmann's own break-up, and she lightly but pointedly spoke about the experience of returning to Fårö for the first time since that split as one that felt less-than-great; I don't know if any of that is fueling her performance, but there's something encouraging her to go smaller than you would ever expect an actor to go, building nearly all of her performance in the first two episodes solely out of wordless reactions that demonstrate how fully her character recedes from the world, before turning on the melodramatic Acting! in the third. Even more boldly, she allows Marianne's opening up and discovery of her own identity manifest in ways that can be brusque and unlikably selfish; if Johan's journey is through wormy, pathetic smallness, Marianne's is through haughtiness and arrogance, before she too arrives at the intimate simplicity of the amazing final scene. For Scenes from a Marriage, in all its length, has the immense decency to end on maybe its single strongest moment (though the sixth episode is a bit lumpy overalland definitely not the series' best, despite having by far the best and, and in-context most moving title - "In the Middle of the Night in a Dark House Somewhere in the World"), when all of the raw, vicious emotion torn open in both actors' faces prior to this point are turned into something warm and patiently amused and understanding. Given how much pain the series plumbs - and how openly horrifying the second half of the fifth episode, "The Illiterates" gets, when Johan's desperation and self-loathing manifest as physical aggression - it's astonishing that it can end on a fundamentally positive, uplifting, pleasant moment, where all the meanness and hatred of the previous hours gives way to two adults who have, at great personal cost, learned how to inhabit the world.

This comes down entirely to Ullmann and Josephson, who carry the film more than any other actors carry any other Bergman project. It's not that it's indifferently crafted - far from it. I have already praised the editing, and I'll add that Sven Nykvist's 16mm cinematography is a masterclass in creating something that looks shabby and shapeless - a lot of jerky handheld camera movement - but always manages, in its tossed-off way, to exactly punctuate the moments that need it. Meanwhile, the murky sea of film grain covering every last frame, besides adding physicality and texture to the actors's faces, makes this feel immediately present and "real" - it reads as documentary footage, basically, which combined with the TV-sized compositions and the tiny number of quotidian locations contributes to the sense of an everyday domestic space spilling out of the screen.

But it's Ullmann and Josephson's show, first and always. The script invests all its faith in their ability to plow through mountains of dialogue and make it feel like their characters are struggling through these thoughts in real time, and as far as I can tell through the language barrier, they're doing it. They, in turn, have to rely on Nykvist's camera to capture their smallest eye flickers and lip movements, little moments of performance so tiny that it's almost hard to believe the actors themselves were aware of them. The whole series is all about the construction of the most terrifyingly intimate moments, and chaining them into a portrait of a marriage collapsing that we, in the audience, understand and feel even more deeply than the characters to. It's a one-of-a-kind triumph; while there was a vogue for divorce-themed movies in the second half of the 1970s (plausibly inspired by this very project), and numerous films, from Woody Allen's Husbands and Wives to Noah Baumbach's Marriage Story, that are clearly direct descendants, no film on this subject has ever come close to matching the sublime intensity and severe honesty of Scenes from a Marriage, which uses its slow development and painfully long duration to let us sink into these characters and the gulf of hurt between them like no other story of this kind that I have encountered in any medium.

Before diving into the series itself, I want to stress the miracle of this series' reception. It was a monstrous hit - 3.5 million people watched the highest-rated fifth episode on Swedish television, more than half of the adult population of the country. The series is widely regarded as having triggered a substantial increase in the country's divorce rate. We have, in other words, the clearest example of something I tried to suggest in connection with Cries and Whispers, which is that Bergman, for all his clout in the art cinema world, actually had the tastes and storytelling instincts of a popular entertainer - he just created popular entertainment on crushing, miserable subjects that involved much gloomy philosophy. But in making his first TV series, he wanted to do right by TV, making something watchable on a mass level.

He achieved this; the viewership numbers show that. Anecdotally, I would, if I could, share a personal story - or a personal story once removed. Many years ago, when I was a wee cinephile, I saw the series for the first time and was bowled over every which way, and I wanted so badly to share it with people. Among these people were my parents, who had been reluctant to watch any Bergman films, owing to his daunting reputation as a miserabilist; I lent them the discs, pointing out that it was only a 50-minute commitment on six consecutive nights, which is certainly how I watched it, and how I recommended they watch it - the pileup of intense, bleak emotions would be almost too much to imagine otherwise. So on a Saturday afternoon, my mother called to tell me they were about to start watching it, wish them luck, the whole thing. And I went about my own day. Five hours later, my mother called again - they had binged all six episodes without a single pause.

I love my parents, but they're not the kind of people who get swept away in a movie or TV show. So for them to be that transfixed by Scenes from a Marriage, enough to let its unblinking view of humans failing to forge emotional bonds crash over them for five uninterrupted hours (something I have, to this day, never had the bravery to try), I think this says something about the unique power of this series. It is unusually watchable for Bergman, to be sure, but not because it is easier to take; on the contrary, my feeling the end of every episode (and part of the reason why I can't watch two of them in a row, let alone six), is that the show has punched through my gut and pulled out my spine. The last beat of every episode is a motherfucker, slicing through the languid rhythms of the 48 preceding minutes in a jarring, disruptive, even mean way, and it makes the experience of watching the series feel like pumping the brakes on a fast car over and over.

But as emotionally draining as it to watch an acrimonious divorce happen in what feels like real time, especially one that has all of those nasty little sucker punches coiled up and ready, Scenes from a Marriage is a gripping, exciting watch. It is television, after all, and Bergman's top priority was crafting something that would be engaging enough not just for the 50 minutes of each episode, but to make you want to come back next week and endure all of this with his protagonists. This is certainly what makes it different from Fanny and Alexander, and arguably what makes it different from Dekalog: Scenes from a Marriage never plays at being a cinematic work that has, for reasons of convenience, found a home on the small screen. It was designed to be seen in that medium, which is part of the reason why I find the existence of a 169-minute reduction of the series that was released in theaters in 1974 (internationally, I believe, though it's almost invariably referred to as the "U.S. cut") so baffling. Okay, not "baffling" - it's for obvious commercial reasons. "Infuriating". Not just because losing nearly two hours of content severely hollows out the material; not just because the perfect shape of the episodes, each telling one complete anecdote about a major event in the life of a married couple, and their ironically bright little epilogues (Bergman narrating the credits over a snatch of Baroque music and beautiful landscape footage from the island of Fårö, where the series was shot), go missing in the onrush of the feature. It's because this feels like something meant to be watched in your living room; we invite this story and these characters into our domestic space as they bang around their own domestic space. It is one of the most deeply intimate works of filmed media I have ever seen, and that feeling of close connection, like the television isn't a window into another world so much as a mirror on the families watching it, is a crucial part of the reason why.

That sure is a lot of words to have not even clearly indicated what Scenes from a Marriage is. In short, Johan (Erland Josephson) and Marianne (Liv Ullmann) have been married for ten years when we meet them, giving an interview to a journalist (Anita Wall) from a lifestyle magazine, an old acquaintance of Marianne's. The purpose of the magazine story - much like the purpose of the miniseries - seems to be to capture something of the essence of an aggressively normal bourgeois marriage. Certainly nothing about either of these people seems exceptional, and it is not the argument of Scenes from a Marriage that they are. This is an argument that unexceptional people can still be rich, unbearably rich subjects for psychological inquiry. Anyway, we learn during the interview that Johan, at 42, is a cocksure blowhard, and that Marianne, at 35, has absolutely no sense of self that isn't defined in terms of her role in a family, and they are perfectly happy with each other, no need for self-reflection. And this persists even after they celebrate the publication of the magazine article by hosting another couple for dinner, only to have that couple - Katarina (Bibi Andersson, stunning and potent in her brief final appearance in a Bergman film) and Peter (Jan Malmsjö) get into a deeply vicious and cutting argument right in front of them.

Over the course of the next four episodes, spanning three years, we will learn, as will the characters, that the marriage is held together by inertia rather than truth, that Johan feels bored enough to run away with another woman, that being forced to fend for herself is good for Marianne's emotional well-being, that Johan's bluster is a mask for deep, uncontrollable insecurity. And then the sixth episode skips ahead seven years, to what would have been the couple's twentieth wedding anniversary, to find that they are both wiser, and maybe not even sadder, and that it only took a little thing like a rancorous divorce for them to realise how much they valued one another's presence in their lives.

All of this is small and pointedly minimalist: three of the episodes (3, 4, and 5, to be exact) contain no other actors than Ullmann and Josephson, and one of them (5) is in real-time. It's the closest to theater that any of Bergman's films ever got, and accordingly, it was later turned into a stage production, though I doubt very much that was to its benefit; just because the series strips the chamber drama down to its sparest essence (this was, in effect, the end of Bergman's dalliance with cinematic chamber dramas, the director having perhaps realised that this perfected the form) does not mean that it's not using its visuals in a tremendously careful way. For in addition to being Bergman's ultimate character drama, it his ultimate experiment in close-ups, and I don't mind saying that Scenes from a Marriage is where I first realised that nothing, but nothing, was a more profound cinematic subject than the human face, boxed into the frame with no room for us to look at anything but the smallest grace notes of expression and performance.

The cinematic structure of Scenes from a Marriage is, in fact, at the level of shot scales: while the close-ups dominate my brain so fully that I tend to remember the series as five uninterrupted hours of them, Bergman and editor Siv Lundgren hang onto them very judiciously (I would go so far as to call this the best-edited project of the director's career). The show's default state is epic-length takes of Ullmann and Josephson having different kinds of arguments - sometimes sharp and hostile ones, sometimes confused and hurt ones, most often just conversations where neither participant quite realises that that they're using the same words to mean different things and so a whole lot of air is spend circling around simple ideas. Because there are so many long takes, every single cut carries an enormous amount of meaning, exploding like a small bomb. In the first episode, "Innocence and Panic", Marianne follows Johan's smooth, perfectly-formed self-narrative with a meandering, repetitive attempt to describe her life and her feelings, straining like an idiot to form a compelling thought, with Ullmann exuding a look of nervous confusion. In the middle of this, the film cuts to the interviewer confidently asking a new question, and the sudden throttling-back of pressure is palpable, like not just the interviewer but the film itself has taken pity on Marianne in her low-grade panic. That's the first really noticeable, powerful cut, but there are plenty to come: places where the show quietly but insistently informs us that watching someone listening will be more important than watching someone talking, controlling how we perceive conversations by controlling who is visually "winning". Changes in shot scale work within that framework to mark out intensification in the argument, sometimes serving as our only real indication that such intensification has taken place, until it erupts into open conflict, perhaps minutes later.

Also, sometimes, the editing is just there to focus our attention like a telescope on Ullmann's performance. Scenes from a Marriage contains, in Erland Josephson's performance, a tremendous piece of acting, moving from unreflective egotism to reflective, guilty egotism, to pathetic, loathsome desperation, finally ending a place of worn-out warmth and peace in the finale scene; and despite this, he is indisputably the less-interesting, weaker actor. Ullmann's work is medium-defining; I'm not even completely sure it's my favorite performance she gave for Bergman, but I'd also be open to the argument that it's the best piece of screen acting in history. Scenes from a Marriage was based in part on Bergman and Ullmann's own break-up, and she lightly but pointedly spoke about the experience of returning to Fårö for the first time since that split as one that felt less-than-great; I don't know if any of that is fueling her performance, but there's something encouraging her to go smaller than you would ever expect an actor to go, building nearly all of her performance in the first two episodes solely out of wordless reactions that demonstrate how fully her character recedes from the world, before turning on the melodramatic Acting! in the third. Even more boldly, she allows Marianne's opening up and discovery of her own identity manifest in ways that can be brusque and unlikably selfish; if Johan's journey is through wormy, pathetic smallness, Marianne's is through haughtiness and arrogance, before she too arrives at the intimate simplicity of the amazing final scene. For Scenes from a Marriage, in all its length, has the immense decency to end on maybe its single strongest moment (though the sixth episode is a bit lumpy overalland definitely not the series' best, despite having by far the best and, and in-context most moving title - "In the Middle of the Night in a Dark House Somewhere in the World"), when all of the raw, vicious emotion torn open in both actors' faces prior to this point are turned into something warm and patiently amused and understanding. Given how much pain the series plumbs - and how openly horrifying the second half of the fifth episode, "The Illiterates" gets, when Johan's desperation and self-loathing manifest as physical aggression - it's astonishing that it can end on a fundamentally positive, uplifting, pleasant moment, where all the meanness and hatred of the previous hours gives way to two adults who have, at great personal cost, learned how to inhabit the world.

This comes down entirely to Ullmann and Josephson, who carry the film more than any other actors carry any other Bergman project. It's not that it's indifferently crafted - far from it. I have already praised the editing, and I'll add that Sven Nykvist's 16mm cinematography is a masterclass in creating something that looks shabby and shapeless - a lot of jerky handheld camera movement - but always manages, in its tossed-off way, to exactly punctuate the moments that need it. Meanwhile, the murky sea of film grain covering every last frame, besides adding physicality and texture to the actors's faces, makes this feel immediately present and "real" - it reads as documentary footage, basically, which combined with the TV-sized compositions and the tiny number of quotidian locations contributes to the sense of an everyday domestic space spilling out of the screen.

But it's Ullmann and Josephson's show, first and always. The script invests all its faith in their ability to plow through mountains of dialogue and make it feel like their characters are struggling through these thoughts in real time, and as far as I can tell through the language barrier, they're doing it. They, in turn, have to rely on Nykvist's camera to capture their smallest eye flickers and lip movements, little moments of performance so tiny that it's almost hard to believe the actors themselves were aware of them. The whole series is all about the construction of the most terrifyingly intimate moments, and chaining them into a portrait of a marriage collapsing that we, in the audience, understand and feel even more deeply than the characters to. It's a one-of-a-kind triumph; while there was a vogue for divorce-themed movies in the second half of the 1970s (plausibly inspired by this very project), and numerous films, from Woody Allen's Husbands and Wives to Noah Baumbach's Marriage Story, that are clearly direct descendants, no film on this subject has ever come close to matching the sublime intensity and severe honesty of Scenes from a Marriage, which uses its slow development and painfully long duration to let us sink into these characters and the gulf of hurt between them like no other story of this kind that I have encountered in any medium.

Categories: domestic dramas, ingmar bergman, scandinavian cinema, television