The magic lantern

Every film director in the history of the medium has made, or will have made, their final film. Most of them scrape out some dumb nonsense, the kind of half-assed project that a fading, aging artist can get financed. The lucky ones are able to do so at least semi-knowingly, ending their career on a high note that tries to do something special and meaningful, or at least in the case of Alfred Hitchcock's Family Plot, taking the piss in an especially blithe way. The luckiest ones of all get to have their final film serve as a consummating work, one that is not merely a graceful exit, but a definitive, career-spanning declaration of intent and artistic purpose, gathering up all they have ever done into a complete argument. I can only think of two filmmakers who have actually succeeded at doing the latter, and both of them had to flagrantly cheat. Agnès Varda hedged her bets by making a final summary work multiple times over the last two decades of her life, with at least three projects (The Beaches of Agnès, Agnès de ci de là Varda, and Varda by Agnès) that were clearly meant to be her swan song, and you could probably make it four by adding The Gleaners and I.

As for Ingmar Bergman's Fanny and Alexander, which is what we're here to discuss, he basically conceived of it from the ground up as the monument to everything he had ever cared about as an artist, a massive five-and-a-half-hour beast that was in many ways one of the least-characteristic films of his career, with the idea being that he would challenge himself on every level to make the ultimate movie of his life, and maybe of everybody else's life as well. And quite a magnificent final film it is, too, if you ignore the part where he had 21 years left in his career after it came out, and it's only his "final film" according to some awfully tendentious word games that define this made-for-TV, released-in-theaters project as a work of cinema in a way that the made-for-TV, released-in-theaters likes of 1984's After the Rehearsal, 1986's The Blessed Ones, 1997's In the Presence of a Clown, and 2003's Saraband all aren't, for whatever reason. To be fair, there is a reason, which is that Fanny and Alexander was released theatrically before it played (in a different cut) on television), and I'm not certain that the other four were released theatrically in Sweden at all. Still, it's a pretty fine distinction, and clearly one Bergman only insisted on for the sake of preserving the grand weight of Fanny and Alexander, which is certainly a more prodigious and magnificent work than any of those.

And as far as that goes, why not let him have it? Fanny and Alexander is an astonishing achievement, not merely the most ambitious thing Bergman had ever produced, but arguably the most ambitious thing in the history of the Swedish film industry, such a grandiose production that it essentially used up all of the budget for the entire nation for a year (that's not actually, true, but it did come under considerable fire for vacuuming up money allotted to the national film funding agency that in principle should have gone to filmmakers without Bergman's international renown and established career, or at least filmmakers who hadn't just spent four years outside of the country after a tax controversy). It's the kind of movie that declares that it's explicit intention is to contain literally everything that cinema can be, and comes rather shockingly close to making good on that intention; a work of the most swaggering arrogance that basically needed to be a perfect, unprecedented masterpiece in order for that arrogance to justify itself so thoroughly that you basically never once think about it while watching the movie.

Before diving into it - and by Christ, there's a lot to dive into - let's clear out the low-hanging fruit. Fanny and Alexander exists in two different versions, owing to the way it had to be produced. Even a man as famous and internationally bankable as Ingmar Bergman wasn't going to just fall into millions of dollars to make a five-hour movie, and the only way Fanny and Alexander could be financed was as a television miniseries, with a considerably shorter theatrical feature to precede the miniseries, in the hopes of actually turning a profit. The contract declared that this feature had a limit of two-and-a-half hours. So, early in 1982, after completing a massive, six-month production, Bergman and editor Sylvia Ingemarsson started by cutting 25 hours of footage into the "real" version of the movie, which ended up running a bit longer than planned, around 5 hours and 20 minutes with all the credits placed in. Bergman had already planned, during the shoot, which scenes he'd trim down or cut altogether to get it down to that 2.5-hour limit, and was horrified to discover, once those cuts had been made, that he still had a four-hour film on his hands. Eventually, he and Ingemarsson were able to shave it down to 188 minutes, which the distributors were willing to sign off on, and this is the cut that the world saw first in 1982 and 1983. The full version, in five parts of unequal length, premiered in the fall of 1983, and had its television debut in four episodes starting in December, 1984.

The shorter cut is thus "legitimate" in a way that the 1974 theatrical version of Scenes from a Marriage maybe isn't. It was this cut that won awards around the world, including an unprecedented four Academy Awards (Foreign Language Film, Cinematography, Art Direction, Costuming - it was nominated as well for Bergman's direction and screenplay), the most ever received by a film not made primarily in the English language, and a record matched only twice, by Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon in 2000, and Parasite in 2019. And it was the shorter cut that made all of those "best films ever made" lists that the film did so well on for most of its early life. And I will also say that, as was not the case with Scenes from a Marriage, I wouldn't say that there's no reason to watch the three-hour Fanny and Alexander. It's not just a shorter, more rushed version of the same film (though it is that), it's a slightly different thing, one more hyper-specifically focused on the story of the titular children, carved down to remove almost anything that isn't focused on the main dramatic spine. These cuts caused Bergman evident pain, and there are at least a couple of leftover moments that feel like signposts for plot points that never end up appearing, but mostly it's a well-done condensation, like a very well-done film adaptation of a Dickens novel. The longer cut (which Bergman supposedly regarded as a single very long movie to be watched in one day, with a break in between the first two and latter two parts, not as a television miniseries to be seen in four chunks on successive days) is like reading the novel, in all its richness, and all the depth it gives to the whole messy ensemble - 51 speaking roles! - and its generous helping of phantasmagoria. That is to say, I don't reject the short cut, as I reject the short Scenes from a Marriage, but there's not really a single thing you gain from it, and several precious things you lose. So the rest of this review is based exclusively on the longer cut.

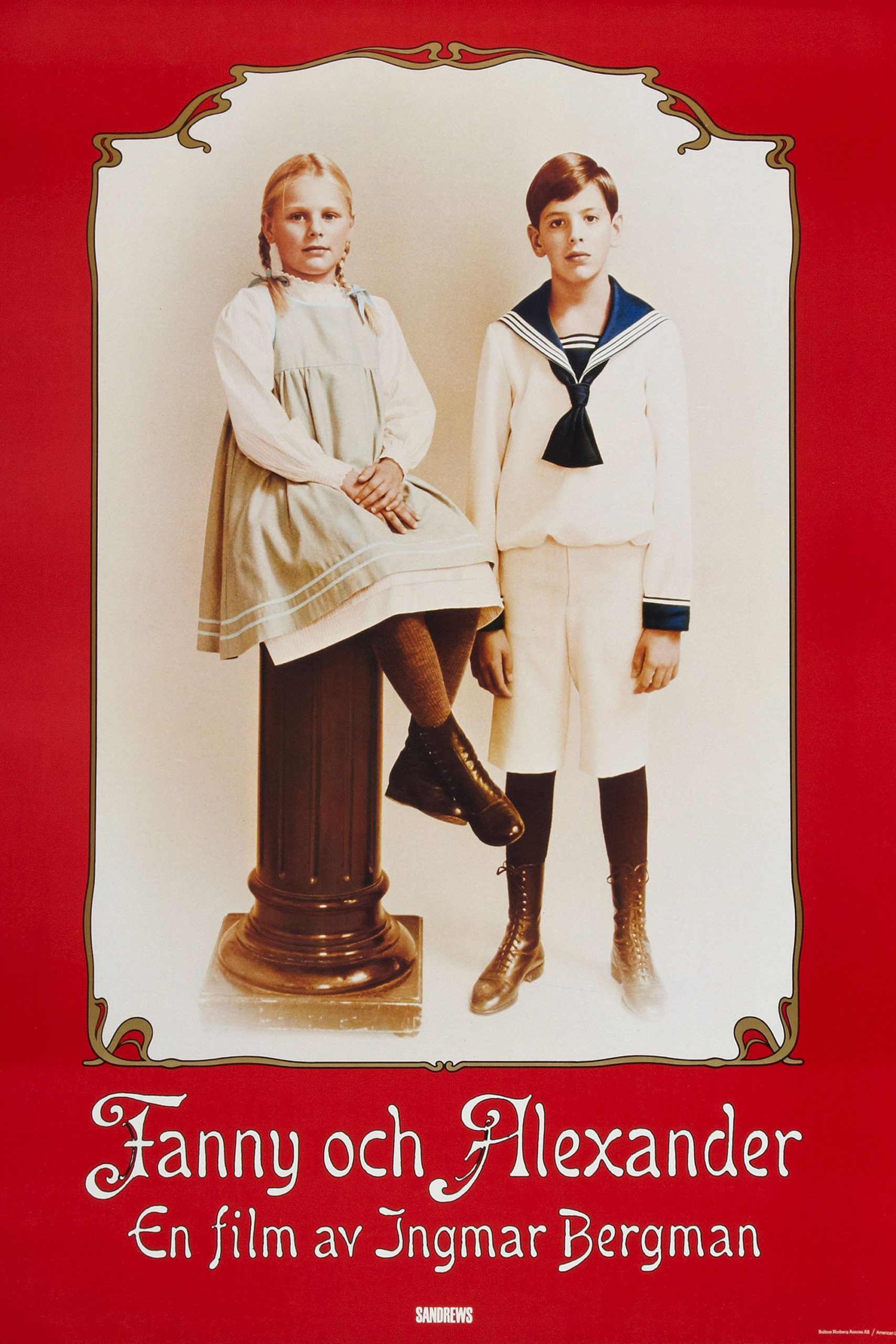

A Dickens novel, I just called it, and that's no accident. Dickens was one of the main touchstones Bergman himself identified, along with Ibsen and Strindberg (the latter of whom is of course always an important touchstone for this filmmaker). And there is much that is Dickensian in the main bulk of the story, though not so much in the unapologetically bourgeois sensibility and setting. Reducing the sprawl of the story just to its key points, Alexander (Bertil Guve) and his younger sister Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) are the children of Oscar Ekdahl (Allan Edwall), one of three Ekdahl brothers of Uppsala, and his much younger wife Emilie (Ewa Fröling). Shortly after Christmas, Oscar dies, and some time after that, Emilie remarries Bishop Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjö), himself a widower who lost his wife and both children under at least semi-dubious circumstances. While Emilie is optimistic at first that this will prove a happy, stablising marriage, Vergérus is very quickly found to be merciless, cruel tyrant who runs his house according to a punishing litany of rules, and operates from a place of fear, rather than love. She tries to leave the marriage, but Vergérus holds the threat of legally separating her children over her, at which point the Ekdahl family, and Isak Jacobi (Erland Josephson), a dear old friend and occasional lover of Ekdahl matriarch Helena (Gunn Wållgren) begin to conspire on ways they might be able to save the children from their wicked stepfather.

That gets us where we need to be, but it misses out on all the rich color and detail that Bergman and his collaborators flood the film with, as well as the vitality of the Ekdahl family writ large, as well as young Alexander's visionary experiences with ghosts, including the sad spectre of his own father, who was rehearsing the role of the ghost of Hamlet's father in a production of Hamlet that was to be staged in the new year at the Ekdahl family theater when he died. That's another thing my nice little summary missed out on: Fanny and Alexander is a movie utterly besotted with the theater, making Oscar's main function as the least-important of the Ekdahls to run the theater in Uppsala that the family has owned for some time, and to pass his love of theatricality, storytelling, and performance on to Alexander. Indeed, the very first shot of the short cut, and the second shot in the longer cut (after an image of rushing water, with the film's title laid over it - all five of the film's acts are introduced with the film's title over a different shot of water), is a pan down the facade of a small puppet theater, with the paper curtain rising to reveal Alexander himself, facing towards the camera, positioning dolls on the stage. Alexander is transparently an alter ego for Bergman himself, in a film of pronounced autobiographical overtones that never quite forces itself into the narrow hole of "autobiography". Though it would, in fairly short order, inaugurate a series of more explicitly autobiographical scripts by Bergman, most of which would be directed by other people.

A head-over-heels love of theatricality - the joy of going out there and putting on a show, the awareness of performance and stagecraft, the broad strokes, at times nearly ending up in outright essentialism, of the emotions and psychological types at play - suffuses every frame of Fanny and Alexander, particularly in the extended cut, which spends much more time at the theater including restoring almost all of the final, small performance given by Gunnar Björnstrand in a Bergman film (the actor was suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer's disease, and had a difficult time remembering his lines; his tiny role as an aging actor is designed to accommodate and acknowledge that, while also serving as a great big farewell hug to the first and most persistent member of Bergman's legendary stock company). But even without explicit nods to a literal theater, the film is all about a love of putting on a show for people and telling them a great, gripping yarn. By the end of the first, longest act, showing the extended Ekdahl family in a messy sprawl celebrating Christmas, we have seen two of the film's very best scenes: Alexander enthralling his cousins and sister with a very committed performance of a spooky magic lantern show (magic lanterns being a beloved feature of Bergman's own childhood), and shortly thereafter, in a scene horribly missing from the shorter cut, Oscar using nothing but a battered old chair as a prop in spinning an elaborate fantasy tale for the children. That sense of communion between a committed, energetic storyteller and his rapt audience is the heart and soul of Fanny and Alexander, and it's surely no accident that the first sign of Vergérus's cruelty is when, even before the marriage, he takes a great deal of to slowly draw out his verbal humiliation of Alexander for spinning a wild tale to his schoolmates of being sold to a circus. It's a nasty little lie, in the bishop's eyes, but just one more playful flight of fancy to Alexander, and Vergérus's inability to understand the difference - to fail to comprehend that stories and fantasy are a crucial part of human life - is the first sign of his own inhumanity.

This love of engaging storytelling isn't just a main subject of Fanny and Alexander, it's the form as well. With very few exceptions (maybe even just Persona and From the Life of the Marionettes), Bergman's films are not meant to be difficult, notwithstanding his historical importance as one of the first international superstars of art cinema; he was a showman, putting on big, graspable stories about big, graspable emotions, even when they were generated by opaque, thorny questions. Even so, Fanny and Alexander is maybe the most accessible, likable, watchable film of his mature career, notwithstanding its monstrous running time; it does not want to challenge us much at all. This manifests in several ways, including perhaps the most transparent style he ever used - and coming right after the shockingly austere Marionettes, no less - notably including almost none of the probing, surgical use of close-ups that marks out virtually every other one of his important films. This isn't to say that it's not well-made; it is, breathtakingly so. Anna Asp's production design & Susanne Lingheim's set decoration, and Marik Vos's costumes earned every molecule of those Oscars, both among the most justified winners in the history of either of those categories. The sets, in particular, are enormously important factors in how the film as a whole works, with the overstuffed sprawl of props and lively color of the Ekdahl Christmas celebrations proving a blatant, jarring contrast to the plain, scuffed white walls of the bishop's miserably austere home, which is then replaced by the cosy dark nooks of Jacobi's store and, at last, softer, more spring-like colors for the Ekdahl home late in the film, when winter ls literally and figuratively over, and rebirth can happen.

And while this is not anywhere close to the most sophisticated visual storytelling of Bergman and Sven Nykvist's shared career, that's not to say that the images are a mere afterthought. It's a very beautiful film, focusing on providing a full range of color (itself a nice break from Nykvist's elaborate use of browns in his later Bergman collaborations), and using sharp focus and soft lighting to create a gentle realism that suggests early 19th Century painting in its purposeful lack of overt stylisation. While the film lacks the pointed use of singles and shot scale that I generally expect of a Bergman film, there are several carefully-managed moments throughout the film; Emilie's wedding to the bishop, for example, which moves between several group shots as we hear Malmsjö's disembodied voice, before landing on the back of his head, as Fröling looks at him in profile; as if we needed more evidence by now that he was emotionally closed-off an unlikable. And then it's punctuated by the scene's first close-up, of Alexander, who looks offscreen to a wide shot of his father's ghost, a shockingly empty space after all the full group shots, with a zoom towards him underlining the moment. There are other moments of such carefully visual storytelling as well, as there'd have to be; in a film this long, made by people this talented, great moments of subtle imagery would have to show up if only by accident.

So anyway, Fanny and Alexander is extremely elegant and well-made, simple and straightforward in the way that only great art with nothing to prove can be simple and straightforward and this is the heart of its monumental strength. It is not psychologically acute and emotionally devastating in the way of all Bergman's other masterpieces; Alexander, the only character we spend a lot of time with, is mostly someone who reacts, and his active personality is almost entirely about honing his skills as an ace storyteller; Fanny, who functions in this film as its most thoughtful and perceptive observer, exists mostly as his anchor. The adults are almost all presented in terms of the big, smudgy concepts they represent to the children, though Emilie gets a bit more depth. And oddly, so does Helena, though this is in part because Wållgren (in her only screen collaboration with Bergman, despite a long and legendary career) is giving easily the most humane and full performance in the film - her warm smile, tinged with the sadness of old age at the corner of her eyes, when she stands before a window in medium close-up and declares that her family is arriving, is my favorite single image of the film, and the one that best gets at the gently detached nostalgia and love of life that are the central emotions of the film. But even some of the best actors in the cast - such as Josephson, or Harriet Andersson, playing a scared maid at the Vergérus home - are willing to play their parts as simple, obvious emotional states, the better to get at the child's eye view of history and family that the film presents as its surface level, even as its undertones are more adult in their understanding of the ways that humans can be complicated, messy, confused, and vicious. To be clear: these are the right performances, well-managed by the actors. Malmsjö is especially good at playing a man of vampiric menace who still feels like a human being, well-motivated and spiritually upstanding in his own mind. It's just they are not naturalistic performances, leaning into grotesque extremes even when they are warm and lovable - Börje Ahlstedt, as the sloppy, vulgar Uncle Carl Ekdahl (the first of several Uncle Carls he'd play in Bergman projects, though the others aren't meant to be the same character), is an especially keen example.

One does not, after all, cite Dickens as a primary inspiration because one wishes to run away from bold essentialist gestures, colorfully distinctive smudges for characters, and full-throated populism. And Dickens strikes me as the main touchstone to the film, despite the obvious Strindberg influences, including a film-ending cameo for A Dream Play, a text Bergman grappled with throughout his career. As well as the increasing quantity of ghostly, dreamlike elements and expressionism, such as the arrival of some dramatically well-timed thunderstorms in the second half. And these things are themselves big, bold, populist touches, more focused on giving us a good story and sweeping us away in the flush of big emotions.

The film is, thanks to all of this, one of cinema's finest portrayals of robust, overripe humanity, good and evil alike, a circus of vivid characters in an exceptionally full and lavish world. It's an odd late turn for Bergman to make in his career, but he makes it brilliantly. There might not be a better costume drama in all of cinema, using warm hues of nostalgia to tell a story that feels fresh and lively and insistently present; there is certainly no film of anything close to this length that has such bouncy vitality in every one of its minutes. It is a masterpiece of the first order, in other words, and even if it doesn't really resemble the director's other masterpieces, I don't know of another filmmaker who could have made this exact film with more passion and grandeur and love of cinema, theater, and the power of a great story.

As for Ingmar Bergman's Fanny and Alexander, which is what we're here to discuss, he basically conceived of it from the ground up as the monument to everything he had ever cared about as an artist, a massive five-and-a-half-hour beast that was in many ways one of the least-characteristic films of his career, with the idea being that he would challenge himself on every level to make the ultimate movie of his life, and maybe of everybody else's life as well. And quite a magnificent final film it is, too, if you ignore the part where he had 21 years left in his career after it came out, and it's only his "final film" according to some awfully tendentious word games that define this made-for-TV, released-in-theaters project as a work of cinema in a way that the made-for-TV, released-in-theaters likes of 1984's After the Rehearsal, 1986's The Blessed Ones, 1997's In the Presence of a Clown, and 2003's Saraband all aren't, for whatever reason. To be fair, there is a reason, which is that Fanny and Alexander was released theatrically before it played (in a different cut) on television), and I'm not certain that the other four were released theatrically in Sweden at all. Still, it's a pretty fine distinction, and clearly one Bergman only insisted on for the sake of preserving the grand weight of Fanny and Alexander, which is certainly a more prodigious and magnificent work than any of those.

And as far as that goes, why not let him have it? Fanny and Alexander is an astonishing achievement, not merely the most ambitious thing Bergman had ever produced, but arguably the most ambitious thing in the history of the Swedish film industry, such a grandiose production that it essentially used up all of the budget for the entire nation for a year (that's not actually, true, but it did come under considerable fire for vacuuming up money allotted to the national film funding agency that in principle should have gone to filmmakers without Bergman's international renown and established career, or at least filmmakers who hadn't just spent four years outside of the country after a tax controversy). It's the kind of movie that declares that it's explicit intention is to contain literally everything that cinema can be, and comes rather shockingly close to making good on that intention; a work of the most swaggering arrogance that basically needed to be a perfect, unprecedented masterpiece in order for that arrogance to justify itself so thoroughly that you basically never once think about it while watching the movie.

Before diving into it - and by Christ, there's a lot to dive into - let's clear out the low-hanging fruit. Fanny and Alexander exists in two different versions, owing to the way it had to be produced. Even a man as famous and internationally bankable as Ingmar Bergman wasn't going to just fall into millions of dollars to make a five-hour movie, and the only way Fanny and Alexander could be financed was as a television miniseries, with a considerably shorter theatrical feature to precede the miniseries, in the hopes of actually turning a profit. The contract declared that this feature had a limit of two-and-a-half hours. So, early in 1982, after completing a massive, six-month production, Bergman and editor Sylvia Ingemarsson started by cutting 25 hours of footage into the "real" version of the movie, which ended up running a bit longer than planned, around 5 hours and 20 minutes with all the credits placed in. Bergman had already planned, during the shoot, which scenes he'd trim down or cut altogether to get it down to that 2.5-hour limit, and was horrified to discover, once those cuts had been made, that he still had a four-hour film on his hands. Eventually, he and Ingemarsson were able to shave it down to 188 minutes, which the distributors were willing to sign off on, and this is the cut that the world saw first in 1982 and 1983. The full version, in five parts of unequal length, premiered in the fall of 1983, and had its television debut in four episodes starting in December, 1984.

The shorter cut is thus "legitimate" in a way that the 1974 theatrical version of Scenes from a Marriage maybe isn't. It was this cut that won awards around the world, including an unprecedented four Academy Awards (Foreign Language Film, Cinematography, Art Direction, Costuming - it was nominated as well for Bergman's direction and screenplay), the most ever received by a film not made primarily in the English language, and a record matched only twice, by Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon in 2000, and Parasite in 2019. And it was the shorter cut that made all of those "best films ever made" lists that the film did so well on for most of its early life. And I will also say that, as was not the case with Scenes from a Marriage, I wouldn't say that there's no reason to watch the three-hour Fanny and Alexander. It's not just a shorter, more rushed version of the same film (though it is that), it's a slightly different thing, one more hyper-specifically focused on the story of the titular children, carved down to remove almost anything that isn't focused on the main dramatic spine. These cuts caused Bergman evident pain, and there are at least a couple of leftover moments that feel like signposts for plot points that never end up appearing, but mostly it's a well-done condensation, like a very well-done film adaptation of a Dickens novel. The longer cut (which Bergman supposedly regarded as a single very long movie to be watched in one day, with a break in between the first two and latter two parts, not as a television miniseries to be seen in four chunks on successive days) is like reading the novel, in all its richness, and all the depth it gives to the whole messy ensemble - 51 speaking roles! - and its generous helping of phantasmagoria. That is to say, I don't reject the short cut, as I reject the short Scenes from a Marriage, but there's not really a single thing you gain from it, and several precious things you lose. So the rest of this review is based exclusively on the longer cut.

A Dickens novel, I just called it, and that's no accident. Dickens was one of the main touchstones Bergman himself identified, along with Ibsen and Strindberg (the latter of whom is of course always an important touchstone for this filmmaker). And there is much that is Dickensian in the main bulk of the story, though not so much in the unapologetically bourgeois sensibility and setting. Reducing the sprawl of the story just to its key points, Alexander (Bertil Guve) and his younger sister Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) are the children of Oscar Ekdahl (Allan Edwall), one of three Ekdahl brothers of Uppsala, and his much younger wife Emilie (Ewa Fröling). Shortly after Christmas, Oscar dies, and some time after that, Emilie remarries Bishop Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjö), himself a widower who lost his wife and both children under at least semi-dubious circumstances. While Emilie is optimistic at first that this will prove a happy, stablising marriage, Vergérus is very quickly found to be merciless, cruel tyrant who runs his house according to a punishing litany of rules, and operates from a place of fear, rather than love. She tries to leave the marriage, but Vergérus holds the threat of legally separating her children over her, at which point the Ekdahl family, and Isak Jacobi (Erland Josephson), a dear old friend and occasional lover of Ekdahl matriarch Helena (Gunn Wållgren) begin to conspire on ways they might be able to save the children from their wicked stepfather.

That gets us where we need to be, but it misses out on all the rich color and detail that Bergman and his collaborators flood the film with, as well as the vitality of the Ekdahl family writ large, as well as young Alexander's visionary experiences with ghosts, including the sad spectre of his own father, who was rehearsing the role of the ghost of Hamlet's father in a production of Hamlet that was to be staged in the new year at the Ekdahl family theater when he died. That's another thing my nice little summary missed out on: Fanny and Alexander is a movie utterly besotted with the theater, making Oscar's main function as the least-important of the Ekdahls to run the theater in Uppsala that the family has owned for some time, and to pass his love of theatricality, storytelling, and performance on to Alexander. Indeed, the very first shot of the short cut, and the second shot in the longer cut (after an image of rushing water, with the film's title laid over it - all five of the film's acts are introduced with the film's title over a different shot of water), is a pan down the facade of a small puppet theater, with the paper curtain rising to reveal Alexander himself, facing towards the camera, positioning dolls on the stage. Alexander is transparently an alter ego for Bergman himself, in a film of pronounced autobiographical overtones that never quite forces itself into the narrow hole of "autobiography". Though it would, in fairly short order, inaugurate a series of more explicitly autobiographical scripts by Bergman, most of which would be directed by other people.

A head-over-heels love of theatricality - the joy of going out there and putting on a show, the awareness of performance and stagecraft, the broad strokes, at times nearly ending up in outright essentialism, of the emotions and psychological types at play - suffuses every frame of Fanny and Alexander, particularly in the extended cut, which spends much more time at the theater including restoring almost all of the final, small performance given by Gunnar Björnstrand in a Bergman film (the actor was suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer's disease, and had a difficult time remembering his lines; his tiny role as an aging actor is designed to accommodate and acknowledge that, while also serving as a great big farewell hug to the first and most persistent member of Bergman's legendary stock company). But even without explicit nods to a literal theater, the film is all about a love of putting on a show for people and telling them a great, gripping yarn. By the end of the first, longest act, showing the extended Ekdahl family in a messy sprawl celebrating Christmas, we have seen two of the film's very best scenes: Alexander enthralling his cousins and sister with a very committed performance of a spooky magic lantern show (magic lanterns being a beloved feature of Bergman's own childhood), and shortly thereafter, in a scene horribly missing from the shorter cut, Oscar using nothing but a battered old chair as a prop in spinning an elaborate fantasy tale for the children. That sense of communion between a committed, energetic storyteller and his rapt audience is the heart and soul of Fanny and Alexander, and it's surely no accident that the first sign of Vergérus's cruelty is when, even before the marriage, he takes a great deal of to slowly draw out his verbal humiliation of Alexander for spinning a wild tale to his schoolmates of being sold to a circus. It's a nasty little lie, in the bishop's eyes, but just one more playful flight of fancy to Alexander, and Vergérus's inability to understand the difference - to fail to comprehend that stories and fantasy are a crucial part of human life - is the first sign of his own inhumanity.

This love of engaging storytelling isn't just a main subject of Fanny and Alexander, it's the form as well. With very few exceptions (maybe even just Persona and From the Life of the Marionettes), Bergman's films are not meant to be difficult, notwithstanding his historical importance as one of the first international superstars of art cinema; he was a showman, putting on big, graspable stories about big, graspable emotions, even when they were generated by opaque, thorny questions. Even so, Fanny and Alexander is maybe the most accessible, likable, watchable film of his mature career, notwithstanding its monstrous running time; it does not want to challenge us much at all. This manifests in several ways, including perhaps the most transparent style he ever used - and coming right after the shockingly austere Marionettes, no less - notably including almost none of the probing, surgical use of close-ups that marks out virtually every other one of his important films. This isn't to say that it's not well-made; it is, breathtakingly so. Anna Asp's production design & Susanne Lingheim's set decoration, and Marik Vos's costumes earned every molecule of those Oscars, both among the most justified winners in the history of either of those categories. The sets, in particular, are enormously important factors in how the film as a whole works, with the overstuffed sprawl of props and lively color of the Ekdahl Christmas celebrations proving a blatant, jarring contrast to the plain, scuffed white walls of the bishop's miserably austere home, which is then replaced by the cosy dark nooks of Jacobi's store and, at last, softer, more spring-like colors for the Ekdahl home late in the film, when winter ls literally and figuratively over, and rebirth can happen.

And while this is not anywhere close to the most sophisticated visual storytelling of Bergman and Sven Nykvist's shared career, that's not to say that the images are a mere afterthought. It's a very beautiful film, focusing on providing a full range of color (itself a nice break from Nykvist's elaborate use of browns in his later Bergman collaborations), and using sharp focus and soft lighting to create a gentle realism that suggests early 19th Century painting in its purposeful lack of overt stylisation. While the film lacks the pointed use of singles and shot scale that I generally expect of a Bergman film, there are several carefully-managed moments throughout the film; Emilie's wedding to the bishop, for example, which moves between several group shots as we hear Malmsjö's disembodied voice, before landing on the back of his head, as Fröling looks at him in profile; as if we needed more evidence by now that he was emotionally closed-off an unlikable. And then it's punctuated by the scene's first close-up, of Alexander, who looks offscreen to a wide shot of his father's ghost, a shockingly empty space after all the full group shots, with a zoom towards him underlining the moment. There are other moments of such carefully visual storytelling as well, as there'd have to be; in a film this long, made by people this talented, great moments of subtle imagery would have to show up if only by accident.

So anyway, Fanny and Alexander is extremely elegant and well-made, simple and straightforward in the way that only great art with nothing to prove can be simple and straightforward and this is the heart of its monumental strength. It is not psychologically acute and emotionally devastating in the way of all Bergman's other masterpieces; Alexander, the only character we spend a lot of time with, is mostly someone who reacts, and his active personality is almost entirely about honing his skills as an ace storyteller; Fanny, who functions in this film as its most thoughtful and perceptive observer, exists mostly as his anchor. The adults are almost all presented in terms of the big, smudgy concepts they represent to the children, though Emilie gets a bit more depth. And oddly, so does Helena, though this is in part because Wållgren (in her only screen collaboration with Bergman, despite a long and legendary career) is giving easily the most humane and full performance in the film - her warm smile, tinged with the sadness of old age at the corner of her eyes, when she stands before a window in medium close-up and declares that her family is arriving, is my favorite single image of the film, and the one that best gets at the gently detached nostalgia and love of life that are the central emotions of the film. But even some of the best actors in the cast - such as Josephson, or Harriet Andersson, playing a scared maid at the Vergérus home - are willing to play their parts as simple, obvious emotional states, the better to get at the child's eye view of history and family that the film presents as its surface level, even as its undertones are more adult in their understanding of the ways that humans can be complicated, messy, confused, and vicious. To be clear: these are the right performances, well-managed by the actors. Malmsjö is especially good at playing a man of vampiric menace who still feels like a human being, well-motivated and spiritually upstanding in his own mind. It's just they are not naturalistic performances, leaning into grotesque extremes even when they are warm and lovable - Börje Ahlstedt, as the sloppy, vulgar Uncle Carl Ekdahl (the first of several Uncle Carls he'd play in Bergman projects, though the others aren't meant to be the same character), is an especially keen example.

One does not, after all, cite Dickens as a primary inspiration because one wishes to run away from bold essentialist gestures, colorfully distinctive smudges for characters, and full-throated populism. And Dickens strikes me as the main touchstone to the film, despite the obvious Strindberg influences, including a film-ending cameo for A Dream Play, a text Bergman grappled with throughout his career. As well as the increasing quantity of ghostly, dreamlike elements and expressionism, such as the arrival of some dramatically well-timed thunderstorms in the second half. And these things are themselves big, bold, populist touches, more focused on giving us a good story and sweeping us away in the flush of big emotions.

The film is, thanks to all of this, one of cinema's finest portrayals of robust, overripe humanity, good and evil alike, a circus of vivid characters in an exceptionally full and lavish world. It's an odd late turn for Bergman to make in his career, but he makes it brilliantly. There might not be a better costume drama in all of cinema, using warm hues of nostalgia to tell a story that feels fresh and lively and insistently present; there is certainly no film of anything close to this length that has such bouncy vitality in every one of its minutes. It is a masterpiece of the first order, in other words, and even if it doesn't really resemble the director's other masterpieces, I don't know of another filmmaker who could have made this exact film with more passion and grandeur and love of cinema, theater, and the power of a great story.