Censor sensibility

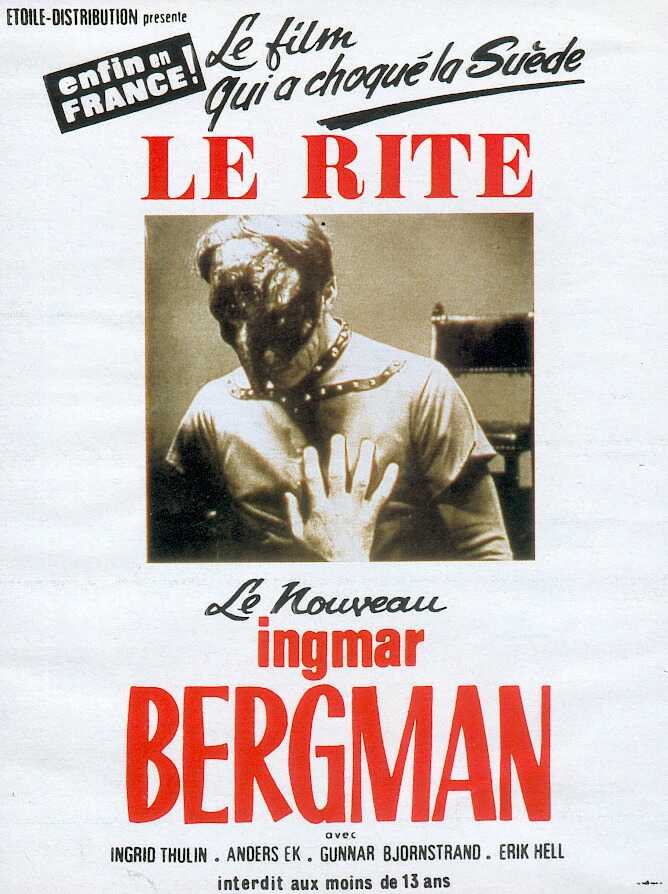

I am quite sure that I would never have supposed that a filmmaker working in the 1960s would leap to television because of the freedoms it offered. And I have no idea if that's what actually took place with The Rite, director Ingmar Bergman's sixth made-for-TV movie, and the first that wasn't a staging of a preexisting play. But it is, arguably, the most aggressively strange and aesthetically hostile film of his career to that point, and his career to that point included Persona, I will remind you. It is a freaky, bizarre, nasty little thing, at times in a heavily sexualised way that feels even less like TV than the rest of it. The film is an assault, and while I'm not sure that it gets us anyplace worth going, I can't help but love the fact that a filmmaker so near the height of his fame and marketability would elect to spend some of his goodwill on such a rancid, jagged little piece of undiluted anger.

And we do know it comes from a place of anger; more than many of Bergman's films, The Rite seems like it's begging us to read it through his claims of how it functions autobiographically and what was going on in his life that inspired the writing. I'd like to avoid that temptation, because to be blunt, what I like best about The Rite has almost nothing explicitly to do that, but it would be simply awful of me not to at least report that this came at the end of years of frustration with the Royal Dramatic Theatre, where he had served as managing director from 1963-'66, annoyed at being constantly hemmed in by censorship and the tastes of the bureaucrats he had to answer to. The Rite is his heavily symbolic attempt to lash out, telling the story of three avant garde theater actors - each "semi-consciously" based on an element Bergman saw in his own personality - being confronted with the small-minded tyranny of a judge who is trying to determine whether they have violated obscenity laws, but mostly enjoys having the freedom to work his will over the insecure artists, tormenting them until they rise up to use the power of their art to work their revenge against him.

Focus too much on the autobiographical elements, and it starts to look silly and petty: an artist who was grumpy that he had answer to any authority sticking his tongue out for 75 minutes. So let's not focus on them. The Rite is much more interesting than a collection of trivial fun facts; it is, in a way, an attempt to comment on the nature of theater and stage acting by breaking the form of cinema and cinematic acting, and its four lead roles (a fifth onscreen character is played by Bergman himself, in a cameo - a priest hearing confession, and make of that just as much as you will) bear witness to what is surely, beat-for-beat, the most unusual acting in any Bergman film up to that point, though I'm certainly not going to argue anything about its quality. I don't think it makes any sense at all to use words like "best or worst" in the context of acting that is so deliberately and thoroughly bizarre as what we see in The Rite, which as much as it is anything, seems to be an exercise in seeing what different kinds of theatricalised screen acting can be expressed by actors sufficiently dedicated to stepping away from anything that resembles naturalism and in the direction of something like spoken-word pantomime. And the fact that I have to invent an incoherent, self-negating concept like "spoken-word pantomime" to get at what the hell is up with the actors in The Rite is, I think, a good sign of, well, what the hell is up with the actors in The Rite.

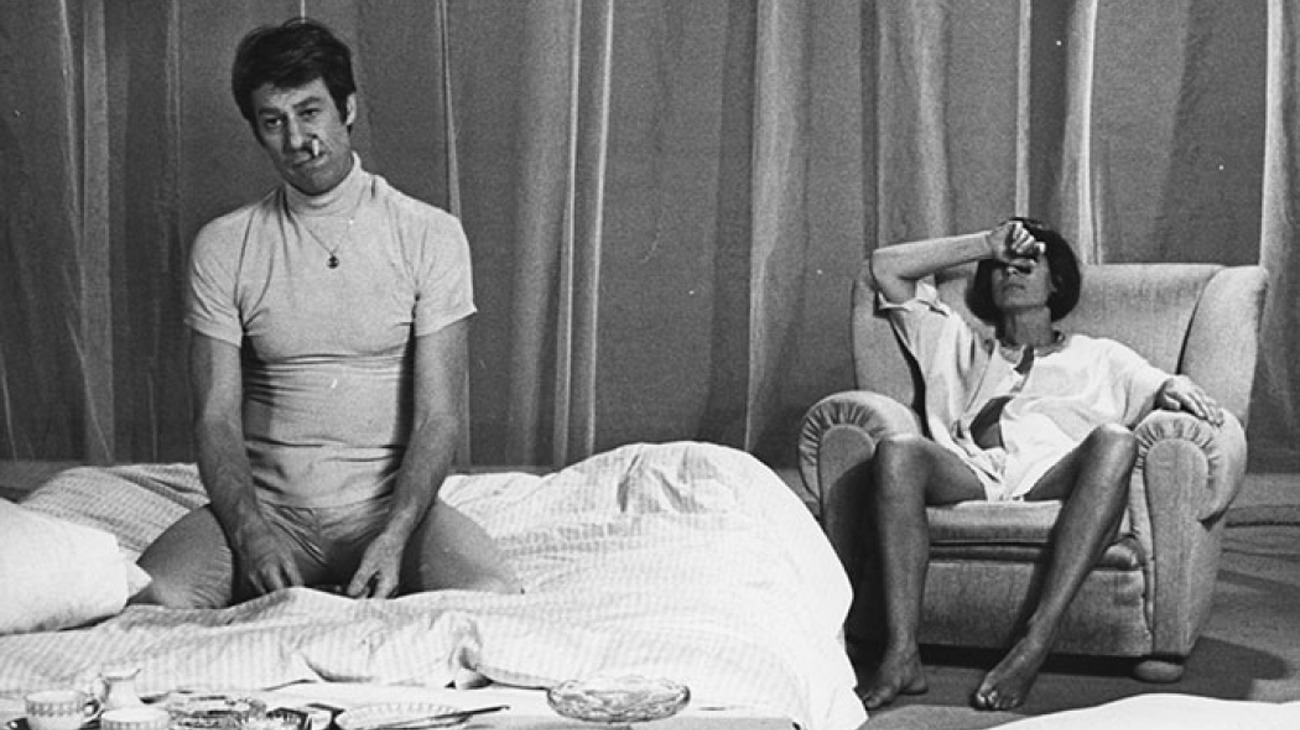

The cast consists entirely of people whom Bergman knew well, from working with them in films, theater, or both. The leader of the acting troupe is Hans Winkelmann, a stable, sober authority figure played by Gunnar Björnstrand, the most stable, sober figure in Bergman's stock company; he is directly contrasted by Sebastian Fisher, impulsive and neurotic, ugly in his behavior with women, a creative genius easily thrown into fits of petulance when he gets a setback - he's played by Anders Ek, who had mostly worked with Bergman on stage, having appeared in just two films, but the first of those was as the miserable clown Frost in Sawdust and Tinsel, the director's other major film about the the nature of theater. In between them is "Claudia Monteverdi", né Thea, Hans's wife and Sebastian's lover, intuitive and spiritual but crippled with self doubt and hypersensitive, played as such a character would almost have to be by the most urgent and intense of Bergman's regular stars, Ingrid Thulin (and one hell of an ugly wig. The film's hair game is pretty dire - Björnstrand has his cropped almost to the skull - but the black mat slathered on Thulin's head is next-level shit). Judge Abrahamson, the sadistic arbiter of their fates, is played by Erik Hell, the least-familiar face here, though he had logged time in Bergman films back in the 1940s.

The goal of the project was to assemble people that Bergman knew would bring something interesting so they could knock out of a film in a hurry, and that's exactly what happened. One would never look at The Rite and think that here we have a lavish production that was the beneficiary of a great deal of time and attention. The sets are all spare rooms populated by the furniture necessary for the blocking and not much else, though they feel like deliberately austere real spaces and not the abstract space of a black box theater; everything feels a bit like a cell, little atomised spaces in which the film's nine isolated scenes play out as anecdotes in a vacuum. The usual crew heads are on hand: costumes and set design by Mago, and cinematography by Sven Nykvist, who gets to show off his extraordinary skills in black and white with Bergman one last time before they switched over to color. And in both cases, they're doing fantastic work, despite the low budget; the light grey background walls give the whole film a kind of hallucinatory glow. But it's still clearly a film made without any resources to speak of; indeed, part of what's striking about the visuals is how empty and spare they are, so unadorned that they achieve a kind of surrealism through how blandly realistic they have to be.

The focus is on acting here, though, in the film's aesthetic just as much as on its plot. By this point, Bergman had become the foremost director of close-ups in sound cinema, and it's hardly a surprise that a television film would demand an exceptional focus on that particular shot, but there's no preparing for how much of The Rite would take place in the most severe, fragmented shots of faces filling the frame in harsh monochrome, glinting with with sweat, presented at various distorted angles to carve their way into the unsettled emotional disorder of the individuals involved. One early conversation between Hans and Sebastian plays out almost entirely as an exchange of uncomfortably close shots that feel like the film itself is being torn between the two, with Björnstrand's placid, calming smile growing feeling increasingly domineering and authoritarian the more we see it contrasted with Ek's tightly clenched jaw and granite eyes forming sharp little pinpricks. When the exchange moves back to a two shot, the release of tension is palpable.

Ek is easily the most shocking of the four performers, which is at least in part because he has the most mercurial character, the most driven by impetuous anger that the actor can wear like a mask, setting his face into ugly, sharp, angular contortions, while he spits out line after line of dense monologues with a breathless, racing delivery, like language itself disgusts him and he just wants to get through it as fast as possible. In a film made up entirely of jagged edges - in the editing, in the fragments of plot, in the darting rhythm of the narrative - Ek's performance is the most jagged thing of all, cutting through the film by turning the slow-burn philosophy typical of Bergman's writing into little packets of rage. But he's really just doing what everyone in the cast is doing: the adoption of a certain mask-like tendency in playing the characters' emotions through bold expressionist gestures rather than naturalist subleties is the heart and soul of The Rite, made concrete and literal in the actual masks worn during the stately nightmare of the final scene. Here, the rite of the title emerges and Bergman mounts his final argument that live theater is a kind of religious ritual, a spiritual communion between actor and audience that can be transporting and truly dangerous if it is not treated with the utmost care and respect. As it is not by Abrahamson, who just assumes that the actors are involved in dirty storytelling and licentious living.

That's skipping ahead a little bit: as I was saying, the performers are all engaged in similar mask-like presentations of emotion through treating their bodies and faces as objects to be sculpted, more than flesh to be inhabited. This results in several striking scenes of primal emotional expression: Ek's arguments with pretty much anybody, or a terrifying, heartbreaking scene of Thulin robotically making herself up to look like a clown, after which she contorts herself into angular poses at ninety degrees to the camera, through which she channels Thea's howls of fear and self-doubt.

It's all extremely strange - there's no real psychological acuity in the sense we typically think of it, since there's really no way in which any of these figures are realistic humans, either as written or played. The title and the final scene are both telling us the score, really: this whole project is exploring the idea of acting as a ritual of evoking emotions in and for an audience, with the arch artificiality of what we see in the movie attempting to break the medium in a sense, finding any sort of way to pull us closer to the electrifying effect of live performance. We must never forget, Bergman always considered himself a theater director first and foremost, and there's an obvious sense that this pageant of masklike screen acting is his attempt to point cinema towards ancient forms of stage acting. Whether it "works" is tough to say - this is a film that feels impossible to grapple with on one viewing, slight and simple though it is. It is certainly astonishing and baffling, though, and given that its goal is ultimately just to throw us out of any sort of comfortable relationship with the actors we see onscreen, bafflement is as good a result as any.

And we do know it comes from a place of anger; more than many of Bergman's films, The Rite seems like it's begging us to read it through his claims of how it functions autobiographically and what was going on in his life that inspired the writing. I'd like to avoid that temptation, because to be blunt, what I like best about The Rite has almost nothing explicitly to do that, but it would be simply awful of me not to at least report that this came at the end of years of frustration with the Royal Dramatic Theatre, where he had served as managing director from 1963-'66, annoyed at being constantly hemmed in by censorship and the tastes of the bureaucrats he had to answer to. The Rite is his heavily symbolic attempt to lash out, telling the story of three avant garde theater actors - each "semi-consciously" based on an element Bergman saw in his own personality - being confronted with the small-minded tyranny of a judge who is trying to determine whether they have violated obscenity laws, but mostly enjoys having the freedom to work his will over the insecure artists, tormenting them until they rise up to use the power of their art to work their revenge against him.

Focus too much on the autobiographical elements, and it starts to look silly and petty: an artist who was grumpy that he had answer to any authority sticking his tongue out for 75 minutes. So let's not focus on them. The Rite is much more interesting than a collection of trivial fun facts; it is, in a way, an attempt to comment on the nature of theater and stage acting by breaking the form of cinema and cinematic acting, and its four lead roles (a fifth onscreen character is played by Bergman himself, in a cameo - a priest hearing confession, and make of that just as much as you will) bear witness to what is surely, beat-for-beat, the most unusual acting in any Bergman film up to that point, though I'm certainly not going to argue anything about its quality. I don't think it makes any sense at all to use words like "best or worst" in the context of acting that is so deliberately and thoroughly bizarre as what we see in The Rite, which as much as it is anything, seems to be an exercise in seeing what different kinds of theatricalised screen acting can be expressed by actors sufficiently dedicated to stepping away from anything that resembles naturalism and in the direction of something like spoken-word pantomime. And the fact that I have to invent an incoherent, self-negating concept like "spoken-word pantomime" to get at what the hell is up with the actors in The Rite is, I think, a good sign of, well, what the hell is up with the actors in The Rite.

The cast consists entirely of people whom Bergman knew well, from working with them in films, theater, or both. The leader of the acting troupe is Hans Winkelmann, a stable, sober authority figure played by Gunnar Björnstrand, the most stable, sober figure in Bergman's stock company; he is directly contrasted by Sebastian Fisher, impulsive and neurotic, ugly in his behavior with women, a creative genius easily thrown into fits of petulance when he gets a setback - he's played by Anders Ek, who had mostly worked with Bergman on stage, having appeared in just two films, but the first of those was as the miserable clown Frost in Sawdust and Tinsel, the director's other major film about the the nature of theater. In between them is "Claudia Monteverdi", né Thea, Hans's wife and Sebastian's lover, intuitive and spiritual but crippled with self doubt and hypersensitive, played as such a character would almost have to be by the most urgent and intense of Bergman's regular stars, Ingrid Thulin (and one hell of an ugly wig. The film's hair game is pretty dire - Björnstrand has his cropped almost to the skull - but the black mat slathered on Thulin's head is next-level shit). Judge Abrahamson, the sadistic arbiter of their fates, is played by Erik Hell, the least-familiar face here, though he had logged time in Bergman films back in the 1940s.

The goal of the project was to assemble people that Bergman knew would bring something interesting so they could knock out of a film in a hurry, and that's exactly what happened. One would never look at The Rite and think that here we have a lavish production that was the beneficiary of a great deal of time and attention. The sets are all spare rooms populated by the furniture necessary for the blocking and not much else, though they feel like deliberately austere real spaces and not the abstract space of a black box theater; everything feels a bit like a cell, little atomised spaces in which the film's nine isolated scenes play out as anecdotes in a vacuum. The usual crew heads are on hand: costumes and set design by Mago, and cinematography by Sven Nykvist, who gets to show off his extraordinary skills in black and white with Bergman one last time before they switched over to color. And in both cases, they're doing fantastic work, despite the low budget; the light grey background walls give the whole film a kind of hallucinatory glow. But it's still clearly a film made without any resources to speak of; indeed, part of what's striking about the visuals is how empty and spare they are, so unadorned that they achieve a kind of surrealism through how blandly realistic they have to be.

The focus is on acting here, though, in the film's aesthetic just as much as on its plot. By this point, Bergman had become the foremost director of close-ups in sound cinema, and it's hardly a surprise that a television film would demand an exceptional focus on that particular shot, but there's no preparing for how much of The Rite would take place in the most severe, fragmented shots of faces filling the frame in harsh monochrome, glinting with with sweat, presented at various distorted angles to carve their way into the unsettled emotional disorder of the individuals involved. One early conversation between Hans and Sebastian plays out almost entirely as an exchange of uncomfortably close shots that feel like the film itself is being torn between the two, with Björnstrand's placid, calming smile growing feeling increasingly domineering and authoritarian the more we see it contrasted with Ek's tightly clenched jaw and granite eyes forming sharp little pinpricks. When the exchange moves back to a two shot, the release of tension is palpable.

Ek is easily the most shocking of the four performers, which is at least in part because he has the most mercurial character, the most driven by impetuous anger that the actor can wear like a mask, setting his face into ugly, sharp, angular contortions, while he spits out line after line of dense monologues with a breathless, racing delivery, like language itself disgusts him and he just wants to get through it as fast as possible. In a film made up entirely of jagged edges - in the editing, in the fragments of plot, in the darting rhythm of the narrative - Ek's performance is the most jagged thing of all, cutting through the film by turning the slow-burn philosophy typical of Bergman's writing into little packets of rage. But he's really just doing what everyone in the cast is doing: the adoption of a certain mask-like tendency in playing the characters' emotions through bold expressionist gestures rather than naturalist subleties is the heart and soul of The Rite, made concrete and literal in the actual masks worn during the stately nightmare of the final scene. Here, the rite of the title emerges and Bergman mounts his final argument that live theater is a kind of religious ritual, a spiritual communion between actor and audience that can be transporting and truly dangerous if it is not treated with the utmost care and respect. As it is not by Abrahamson, who just assumes that the actors are involved in dirty storytelling and licentious living.

That's skipping ahead a little bit: as I was saying, the performers are all engaged in similar mask-like presentations of emotion through treating their bodies and faces as objects to be sculpted, more than flesh to be inhabited. This results in several striking scenes of primal emotional expression: Ek's arguments with pretty much anybody, or a terrifying, heartbreaking scene of Thulin robotically making herself up to look like a clown, after which she contorts herself into angular poses at ninety degrees to the camera, through which she channels Thea's howls of fear and self-doubt.

It's all extremely strange - there's no real psychological acuity in the sense we typically think of it, since there's really no way in which any of these figures are realistic humans, either as written or played. The title and the final scene are both telling us the score, really: this whole project is exploring the idea of acting as a ritual of evoking emotions in and for an audience, with the arch artificiality of what we see in the movie attempting to break the medium in a sense, finding any sort of way to pull us closer to the electrifying effect of live performance. We must never forget, Bergman always considered himself a theater director first and foremost, and there's an obvious sense that this pageant of masklike screen acting is his attempt to point cinema towards ancient forms of stage acting. Whether it "works" is tough to say - this is a film that feels impossible to grapple with on one viewing, slight and simple though it is. It is certainly astonishing and baffling, though, and given that its goal is ultimately just to throw us out of any sort of comfortable relationship with the actors we see onscreen, bafflement is as good a result as any.