Home on the range

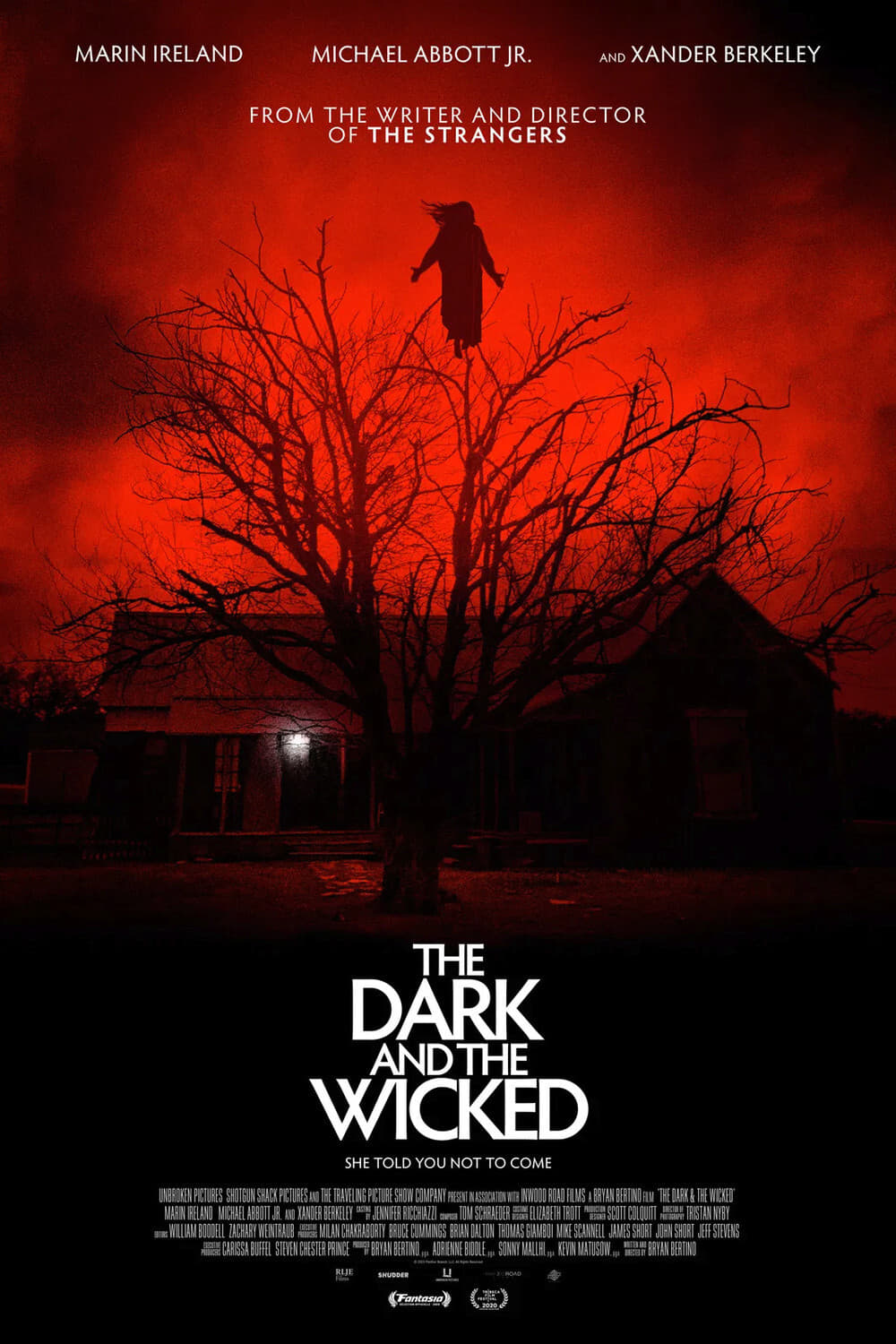

Truth in advertising: The Dark and the Wicked is basically nothing else beyond the two adjectives promised by its title. The fourth film directed by Bryan Bertino (whose failure to generate a high-profile career after his 2008 debut The Strangers remains a bizarre mystery to me) is the latest entry in the blossoming genre of "family drama-horror", and it's at least a solid contribution to the form, but its real strengths lie in its unstinting commitment to following through on its set-up. And that set-up promises that things are going to get extremely cruel and despairing before they get better (if they do). It is never a happy-go-lucky film, but it gets to some places in the last third that are pretty startling in how little catharsis their violent bloodletting affords us. This is not a "hooray we beat the monster" film. It is a "the world is a howling black hole of suffering and we make it worse on ourselves" movie.

So if you're interested in that, what we have here is an old couple living in an old house on a ranch, surrounded by the dull throbbing sound of constant wind, and the mild clatter of goats (played by the ranch where Bertino grew up, no less). It is a remote, gloomy place, made gloomier because the man (Michael Zagst) is nearing death, leaving the woman (Julie Oliver-Touchstone) to stonily go about the business of keeping things going. This is the cheery world that their adult children, Louise (Marin Ireland) and Michael (Michael Abbott, Jr.) return to, with the implication that it has been a very long time since they've seen each other or their parents, and death alone is sufficient to drag them bag to the location of all their pain. That's the "family drama" part. The "horror" part has already been introduced to us in an early scene of the old woman feeding goats: as the noise of their atonal squawking and clamoring around in a pen is ratcheted up on the soundtrack, the editing starts to pick up speed until we're basically just being confronted with a chaotic, noisy mess of images and sound (editors William Boodell and Zachary Weintraub are, arguably, the film's secret MVPs: no matter what else happens, it is immaculately paced at the level of individual cuts). Which is unpleasant and aggressive, but not horror, except for the quick flicker, for the smallest number of frames that the human eye can parse as a stable image, of a grey-skinned human-shape being with reptilian eyes. It'll be a while before the film confirms it, or even necessarily starts to imply it, but yep, there's a demon haunting this family, and it is going to end up doing quite a number on Louise and Michael once it has driven their mother to mutilate and kill herself.

I will be honest: for the first bit of the movie, this all seemed fairly insubstantial. Well-done, but insubstantial. Very little of what we see here is new at all, nor is it surprising: visions of ghosts who look pretty much like dozens of other ghosts in post-J-horror films, a glacially slow tracking shot backwards that is clearly going to end with the revelation of a dead body. The heavy, shadow-dominated cinematography by Tristan Nyby is handsome enough, but it's also rather monotonous, jabbing us over and over with the sheer apocalyptic weight of everything; the constant rumble of wind on the soundtrack does the same thing sonically. There are places where the film makes this familiarity work: the mother mutiliating herself is a good example, since it's extremely obvious the instant the scene begins where it's going to end, and right down to the cutting pattern, it plays out exactly as even the most casual horror fan could predict. And then the film squirms out of our grasp a little bit: once it has "shockingly" fulfilled itself, the moment keeps going on, hammering home the savageness and brutality of the moment for second upon second upon second.

This particular moment ends up neatly foreshadowing the evolution the film makes in its second half. As with The Strangers, Bertino has made a film that's primarily about the domestic security of a family home being violated from an outside force that has no obvious motivation other than the desire to see random people suffer. Here, that outside force is avowedly demonic in nature; rather than being a film about human viciousness and psychopathy, however outlandish in scale and cruelty, The Dark and the Wicked is about genuine, no-two-ways-about-it inhuman evil. It is, at a certain remove, a metaphor for how difficult it is to perceive or comprehend such evil: Louise and Michael are both atheists, and the next-biggest role in the film is neither of their parents, but a priest, played by Xander Berkeley (who counts as the film's "name"), and much of the middle of the film is taken up with the conflict between his way of addressing what's happening to their family versus theirs. But the film doesn't end up doing all that much with it: it's more interested in the devastating toll that such evil has on the people suffering from it, first in purely emotional ways - the demon enjoys manifesting as the dead mother, just for the perverted kick of it - and later as bodily suffering, captured in some gore effects that aren't especially over-the-top, but are presented with such gravity and lack of fun that they end up feeling much more stomach-churning than much messier but gaudier violence might.

In short: the film turns brutal as it goes along, brutal even for a film about siblings traveling home for no reason other than to observe their dad slowly die. The film's main business lies in watching a family collapse, its history and traditions wiped out swiftly and without any sentiment, and this is something it obviously regards as sad and upsetting. It then translates that painful process into the stuff of an aggressive horror movie, in which capricious evil just keeps happening and happening, not looking to do anything, just enjoying the misery of its victims. Maybe we need to blame demons for that kind of thing, maybe it's just the inevitable churn of history. The Dark and the Wicked posits the literal existence of malevolent spirits, but more concerned with what happens when mere humans reach their capacity to keep dealing with bad things, whatever is causing them to come into being. It's quite the opposite of a pick-me-up movie, this is to say, but over the course of its final third, it contrives to pack one hell of a punch, making me feel as all-around distraught as a horror film has in quite a long time, and, well, nobody said it was the job of horror films to be nice.

For more thoughts on the movie, check out Rob & Carrie's interview with producer Adrienne Biddle!

So if you're interested in that, what we have here is an old couple living in an old house on a ranch, surrounded by the dull throbbing sound of constant wind, and the mild clatter of goats (played by the ranch where Bertino grew up, no less). It is a remote, gloomy place, made gloomier because the man (Michael Zagst) is nearing death, leaving the woman (Julie Oliver-Touchstone) to stonily go about the business of keeping things going. This is the cheery world that their adult children, Louise (Marin Ireland) and Michael (Michael Abbott, Jr.) return to, with the implication that it has been a very long time since they've seen each other or their parents, and death alone is sufficient to drag them bag to the location of all their pain. That's the "family drama" part. The "horror" part has already been introduced to us in an early scene of the old woman feeding goats: as the noise of their atonal squawking and clamoring around in a pen is ratcheted up on the soundtrack, the editing starts to pick up speed until we're basically just being confronted with a chaotic, noisy mess of images and sound (editors William Boodell and Zachary Weintraub are, arguably, the film's secret MVPs: no matter what else happens, it is immaculately paced at the level of individual cuts). Which is unpleasant and aggressive, but not horror, except for the quick flicker, for the smallest number of frames that the human eye can parse as a stable image, of a grey-skinned human-shape being with reptilian eyes. It'll be a while before the film confirms it, or even necessarily starts to imply it, but yep, there's a demon haunting this family, and it is going to end up doing quite a number on Louise and Michael once it has driven their mother to mutilate and kill herself.

I will be honest: for the first bit of the movie, this all seemed fairly insubstantial. Well-done, but insubstantial. Very little of what we see here is new at all, nor is it surprising: visions of ghosts who look pretty much like dozens of other ghosts in post-J-horror films, a glacially slow tracking shot backwards that is clearly going to end with the revelation of a dead body. The heavy, shadow-dominated cinematography by Tristan Nyby is handsome enough, but it's also rather monotonous, jabbing us over and over with the sheer apocalyptic weight of everything; the constant rumble of wind on the soundtrack does the same thing sonically. There are places where the film makes this familiarity work: the mother mutiliating herself is a good example, since it's extremely obvious the instant the scene begins where it's going to end, and right down to the cutting pattern, it plays out exactly as even the most casual horror fan could predict. And then the film squirms out of our grasp a little bit: once it has "shockingly" fulfilled itself, the moment keeps going on, hammering home the savageness and brutality of the moment for second upon second upon second.

This particular moment ends up neatly foreshadowing the evolution the film makes in its second half. As with The Strangers, Bertino has made a film that's primarily about the domestic security of a family home being violated from an outside force that has no obvious motivation other than the desire to see random people suffer. Here, that outside force is avowedly demonic in nature; rather than being a film about human viciousness and psychopathy, however outlandish in scale and cruelty, The Dark and the Wicked is about genuine, no-two-ways-about-it inhuman evil. It is, at a certain remove, a metaphor for how difficult it is to perceive or comprehend such evil: Louise and Michael are both atheists, and the next-biggest role in the film is neither of their parents, but a priest, played by Xander Berkeley (who counts as the film's "name"), and much of the middle of the film is taken up with the conflict between his way of addressing what's happening to their family versus theirs. But the film doesn't end up doing all that much with it: it's more interested in the devastating toll that such evil has on the people suffering from it, first in purely emotional ways - the demon enjoys manifesting as the dead mother, just for the perverted kick of it - and later as bodily suffering, captured in some gore effects that aren't especially over-the-top, but are presented with such gravity and lack of fun that they end up feeling much more stomach-churning than much messier but gaudier violence might.

In short: the film turns brutal as it goes along, brutal even for a film about siblings traveling home for no reason other than to observe their dad slowly die. The film's main business lies in watching a family collapse, its history and traditions wiped out swiftly and without any sentiment, and this is something it obviously regards as sad and upsetting. It then translates that painful process into the stuff of an aggressive horror movie, in which capricious evil just keeps happening and happening, not looking to do anything, just enjoying the misery of its victims. Maybe we need to blame demons for that kind of thing, maybe it's just the inevitable churn of history. The Dark and the Wicked posits the literal existence of malevolent spirits, but more concerned with what happens when mere humans reach their capacity to keep dealing with bad things, whatever is causing them to come into being. It's quite the opposite of a pick-me-up movie, this is to say, but over the course of its final third, it contrives to pack one hell of a punch, making me feel as all-around distraught as a horror film has in quite a long time, and, well, nobody said it was the job of horror films to be nice.

For more thoughts on the movie, check out Rob & Carrie's interview with producer Adrienne Biddle!