We fight, we try not to be killed, and sometimes we are. That's all.

The learning curve for early sound cinema was steep and fast. In the immediate wake of the enormously popular sync-sound scenes from 1927's The Jazz Singer, the American film indsutry jumped with great enthusiasm and no planning into making some of the most awkward, unwatchable films of its entire history across the course of 1928, movies that have almost all been forgotten and damn well deserve to be forgotten. By the end of 1929, a few of the most clever and creative filmmakers had figured out some genuinely interesting ways to use sound and image together, and so we get groundbreaking triumphs like Rouben Mamoulian's Applause in October of that year, and Ernst Lubitsch's The Love Parade in November. But even outside of these, the baseline of competence across the industry in working with sound had increased to the point that the average film is merely stiff and unengaging, not outrageously humiliating.

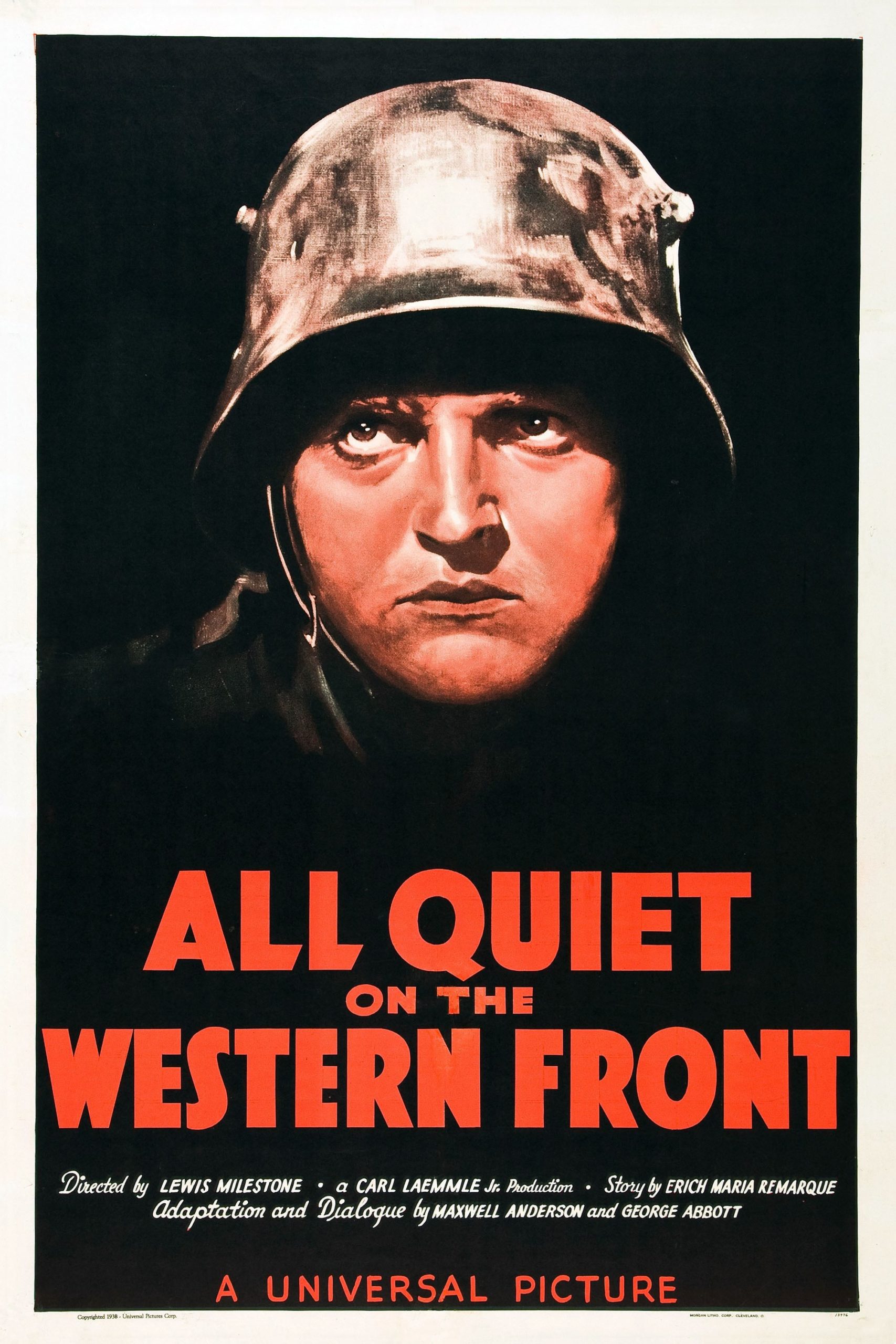

And thus the stage was set for the first bona-fide masterpiece of sound cinema, and it arrived in April of 1930, in the form of All Quiet on the Western Front, an adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque's German-language 1928 anti-war novel. I confess that even in the case of the very best of the best of sound films from 1929, I would hesitate to force them on a normal person without couching them in a lot of hedging about "well, you do need to keep in mind what they were capable of, technologically". No such concerns with All Quiet..., a film that has aged as splendidly as any early sound film is capable of. It is a powerful, gut-wrenching thing, telling a story of unusual fury and passionate righteousness - it's one of the most persuasive anti-war movies ever made, I think - and using sound to further that story and embellish that fury such that it's quite impossible to imagine how that it would work as a silent at all. No American film for years would top it for using sound in a expressive, artful way; in all of early sound filmmaking, I think that Fritz Lang's M in Germany and René Clair's Le Million in France, both from 1931, are the only films that even match it, and they're both being playfully minimalist.

No minimalism here. All Quiet on the Western Front is 100% sonic maximalism, an attempt to instill something close to mortal terror in the viewer solely the use of offscreen sound. This of course happens in the film's celebrated combat sequences, a portrayal of the hell of trench warfare that surrounds the viewer in an envelope of aggressive, unnatural battle noises: rattling bass thumps; shrill whistling mortar shells; sharp, tinny bullets racing by; and of course, human screaming. If there's anything that lets All Quiet... remain a uniquely potent and discomfiting war movie all these years later, I think that must be it: those screams. It is deeply interested in forcing us to confront, over and over, the reality of human suffering. No quick slumping deaths, no actors throwing their hands across their chests and grimacing, then collapsing - death in All Quiet... is drawn out, and it is bloody (or at least as bloody as the prevailing social norms of 1930 permitted; at any rate, the shot of two dripping hands clinging to barbed wire, with no arms or body attached to them, that comes during the films first proper combat scene, packs a whole lot of punch), and it is painful, physically and psychologically. As the story advances, we get more and more of this, but really, the film has done all it needs to just by letting us hear unseen soldiers yelping in pain and terror, and then slowly pulling those screams onscreen, culminating in a moment when the main character, Paul Baumer (Lew Ayres), convinced he's about to be cut open and left to die in an overflowing army hospital, shrieks and shrieks as the camera tries to keep up with the gurney he's being rolled away on.

The film's soundtrack set the standard for all cinematic combat thereafter, defining to some extent what our pop-culture understanding of things like the characteristic sound of mortar shells even is. It says all that needs to be said that Steven Spielberg looked to this film as a primary influence on the deliriously terrifying and chaotic sound effects for the Omaha Beach sequence in his Saving Private Ryan in 1998. And I might even go so far as to say that it took all of those 68 intervening years for somebody to finally make a war movie with a more comprehensively overwhelming soundtrack - and All Quiet on the Western Front had to do it with a monaural sound mix.

But as easy as it is to get carried away with the combat scenes, they're not the only time that the film demonstrates a bold and creative use of sound. Right at the very start, the film demonstrates the amount of elaborate sonic layering we're in for: in the small German town that Paul calls home, a military parade is going by, with loud, martial music squawking out on the soundtrack. As the camera pulls back from an open window - the first of many times that director Lewis Milestone and cinematographer Arthur Edeson (with uncredited help from the great Karl Freund) will utilise internal frames separating the outside and inside, in a visual schema that's not much less accomplished and impressive than the film's radical soundtrack - we find ourselves in a school room, where Professor Kantorek (Arnold Lucy) expounds with great animation to his classroom full of boys. But the loud music holds on, drowning out the teacher's words, and only once we get a nice long chance to see the boisterous interaction of his gestures and the music does the latter start to fade out, almost as though Kantorek's speech grows out of it. And since his "lecture" consists of exhorting the boys to do their patriotic duty and sign up to go off to war, this is kind of exactly what's happening.

From here, the plot goes exactly where it must: the young men, charged with militaristic fervor, join the army for the expected few months until Germany shatters the French and Russian armies. They are first surprised to find that military training is an arduous and unpleasant experience; they are then shocked to find that trench warfare is a hell on earth that makes training seem like play time. We accompany Paul throughout all of this, but he emerges as the film's protagonist only elliptically; Ayres receives no more attention from the camera than anybody else (indeed, the shot introducing him buries him without distinction in a line of similar-looking young men), and it's quite a long way into the film before he gets his first plot beat that belongs to him and him alone. He's just an anonymous grunt for the most part, and what he experiences is clearly meant to be universal to the wartime soldier, not specific to this one character (having all the Germans acted like small-town Americans amplifies this sense - the film looks ahead to 1937's Grand Illusion, the only better WWI film I know of, in approach the war from an an expressly anti-nationalist lens, where all young soldiers are worthy of sympathy and all cold-blooded officers are worthy of scorn).

The point being, the film's strength does not lie in its originality, but its execution, and its intensity. There are certainly bits that feel overwritten, like Paul's big climactic speech to the next generation of boys at Kantorek's school, where Ayres's performance goes from shuffling and flat to bombastic and outraged, justifying the oddly bland approach he's taken to the character up till this scene. There are bits that feel ludicrously melodramatic, like Paul's nervous conversation to the cooling corpse of a French soldier that he's killed, as the boy almost breaks down crying from guilt and fear. There are bits that feel like Universal Pictures was making a Universal Pictures production, with all the strained, cheesy "local color" approach to casting smaller roles, and the general "aw shucks" tenor of the dialogue in George Abbott's screenplay that implies. But the film makes them work, mostly: the overwritten speeches have the unmistakable pungency of real moral outrage, and the scene with the dead soldier takes on an eerie, almost horrifying cast, as Paul grows more and more scattered. The film does excellent work in wearing us out through its loud soundtrack and its shockingly fast pace (the film is, in the restored versions that have been available for the last couple of decades, runs between 131 and 134 minutes, down from a lost 152-minute original; it races by faster than any other equally-long film from its period that I can name), doing something to mimic in the viewer the exhaustion that grows on Paul's face across the movie, and this wearying feeling helps make some of the most melodramatic developments later in the film feel earned, particularly in contrast with the light tone of the earliest scenes.

It is, all told, an immaculately controlled movie, one whose firebreathing message comes through not just in its words but in the tired, disgusted feeling it imparts, leading up to the outrageous shock of its final scene, when the soundtrack finally cuts out completely - because Paul has just died. The film's famous last two shots are absolutely the corniest, tritest bullshit, a butterfly that's hugely obvious symbol for peace being just out of reach followed by a superimposition over a graveyard that's somehow even more obvious in its symbolism. But it's earned, so it works - I've seen the film three times now, I knew how it ended before the first time, and I still feel so horrible in those last 20 seconds, like clockwork. It is powerful, visceral cinema of the first order, filmmaking that builds for more than two hours to hit with laserlike precision at just that last point. It's one of the finest pieces of filmmaking in all of '30s Hollywood, one of the vanishingly rare times that the Academy Award for Best Picture went to the actual best picture of the year, both because of its emotional power and the sublime technique that went into those emotions, and also one of the few Best Picture winners that I think would still be a classic even without that award keeping them in the public eye. For to put it as bluntly as the film's own arguments, this remains one of the only truly and completely anti-war films ever made, as angry after nine decades as the day it premiered.

And thus the stage was set for the first bona-fide masterpiece of sound cinema, and it arrived in April of 1930, in the form of All Quiet on the Western Front, an adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque's German-language 1928 anti-war novel. I confess that even in the case of the very best of the best of sound films from 1929, I would hesitate to force them on a normal person without couching them in a lot of hedging about "well, you do need to keep in mind what they were capable of, technologically". No such concerns with All Quiet..., a film that has aged as splendidly as any early sound film is capable of. It is a powerful, gut-wrenching thing, telling a story of unusual fury and passionate righteousness - it's one of the most persuasive anti-war movies ever made, I think - and using sound to further that story and embellish that fury such that it's quite impossible to imagine how that it would work as a silent at all. No American film for years would top it for using sound in a expressive, artful way; in all of early sound filmmaking, I think that Fritz Lang's M in Germany and René Clair's Le Million in France, both from 1931, are the only films that even match it, and they're both being playfully minimalist.

No minimalism here. All Quiet on the Western Front is 100% sonic maximalism, an attempt to instill something close to mortal terror in the viewer solely the use of offscreen sound. This of course happens in the film's celebrated combat sequences, a portrayal of the hell of trench warfare that surrounds the viewer in an envelope of aggressive, unnatural battle noises: rattling bass thumps; shrill whistling mortar shells; sharp, tinny bullets racing by; and of course, human screaming. If there's anything that lets All Quiet... remain a uniquely potent and discomfiting war movie all these years later, I think that must be it: those screams. It is deeply interested in forcing us to confront, over and over, the reality of human suffering. No quick slumping deaths, no actors throwing their hands across their chests and grimacing, then collapsing - death in All Quiet... is drawn out, and it is bloody (or at least as bloody as the prevailing social norms of 1930 permitted; at any rate, the shot of two dripping hands clinging to barbed wire, with no arms or body attached to them, that comes during the films first proper combat scene, packs a whole lot of punch), and it is painful, physically and psychologically. As the story advances, we get more and more of this, but really, the film has done all it needs to just by letting us hear unseen soldiers yelping in pain and terror, and then slowly pulling those screams onscreen, culminating in a moment when the main character, Paul Baumer (Lew Ayres), convinced he's about to be cut open and left to die in an overflowing army hospital, shrieks and shrieks as the camera tries to keep up with the gurney he's being rolled away on.

The film's soundtrack set the standard for all cinematic combat thereafter, defining to some extent what our pop-culture understanding of things like the characteristic sound of mortar shells even is. It says all that needs to be said that Steven Spielberg looked to this film as a primary influence on the deliriously terrifying and chaotic sound effects for the Omaha Beach sequence in his Saving Private Ryan in 1998. And I might even go so far as to say that it took all of those 68 intervening years for somebody to finally make a war movie with a more comprehensively overwhelming soundtrack - and All Quiet on the Western Front had to do it with a monaural sound mix.

But as easy as it is to get carried away with the combat scenes, they're not the only time that the film demonstrates a bold and creative use of sound. Right at the very start, the film demonstrates the amount of elaborate sonic layering we're in for: in the small German town that Paul calls home, a military parade is going by, with loud, martial music squawking out on the soundtrack. As the camera pulls back from an open window - the first of many times that director Lewis Milestone and cinematographer Arthur Edeson (with uncredited help from the great Karl Freund) will utilise internal frames separating the outside and inside, in a visual schema that's not much less accomplished and impressive than the film's radical soundtrack - we find ourselves in a school room, where Professor Kantorek (Arnold Lucy) expounds with great animation to his classroom full of boys. But the loud music holds on, drowning out the teacher's words, and only once we get a nice long chance to see the boisterous interaction of his gestures and the music does the latter start to fade out, almost as though Kantorek's speech grows out of it. And since his "lecture" consists of exhorting the boys to do their patriotic duty and sign up to go off to war, this is kind of exactly what's happening.

From here, the plot goes exactly where it must: the young men, charged with militaristic fervor, join the army for the expected few months until Germany shatters the French and Russian armies. They are first surprised to find that military training is an arduous and unpleasant experience; they are then shocked to find that trench warfare is a hell on earth that makes training seem like play time. We accompany Paul throughout all of this, but he emerges as the film's protagonist only elliptically; Ayres receives no more attention from the camera than anybody else (indeed, the shot introducing him buries him without distinction in a line of similar-looking young men), and it's quite a long way into the film before he gets his first plot beat that belongs to him and him alone. He's just an anonymous grunt for the most part, and what he experiences is clearly meant to be universal to the wartime soldier, not specific to this one character (having all the Germans acted like small-town Americans amplifies this sense - the film looks ahead to 1937's Grand Illusion, the only better WWI film I know of, in approach the war from an an expressly anti-nationalist lens, where all young soldiers are worthy of sympathy and all cold-blooded officers are worthy of scorn).

The point being, the film's strength does not lie in its originality, but its execution, and its intensity. There are certainly bits that feel overwritten, like Paul's big climactic speech to the next generation of boys at Kantorek's school, where Ayres's performance goes from shuffling and flat to bombastic and outraged, justifying the oddly bland approach he's taken to the character up till this scene. There are bits that feel ludicrously melodramatic, like Paul's nervous conversation to the cooling corpse of a French soldier that he's killed, as the boy almost breaks down crying from guilt and fear. There are bits that feel like Universal Pictures was making a Universal Pictures production, with all the strained, cheesy "local color" approach to casting smaller roles, and the general "aw shucks" tenor of the dialogue in George Abbott's screenplay that implies. But the film makes them work, mostly: the overwritten speeches have the unmistakable pungency of real moral outrage, and the scene with the dead soldier takes on an eerie, almost horrifying cast, as Paul grows more and more scattered. The film does excellent work in wearing us out through its loud soundtrack and its shockingly fast pace (the film is, in the restored versions that have been available for the last couple of decades, runs between 131 and 134 minutes, down from a lost 152-minute original; it races by faster than any other equally-long film from its period that I can name), doing something to mimic in the viewer the exhaustion that grows on Paul's face across the movie, and this wearying feeling helps make some of the most melodramatic developments later in the film feel earned, particularly in contrast with the light tone of the earliest scenes.

It is, all told, an immaculately controlled movie, one whose firebreathing message comes through not just in its words but in the tired, disgusted feeling it imparts, leading up to the outrageous shock of its final scene, when the soundtrack finally cuts out completely - because Paul has just died. The film's famous last two shots are absolutely the corniest, tritest bullshit, a butterfly that's hugely obvious symbol for peace being just out of reach followed by a superimposition over a graveyard that's somehow even more obvious in its symbolism. But it's earned, so it works - I've seen the film three times now, I knew how it ended before the first time, and I still feel so horrible in those last 20 seconds, like clockwork. It is powerful, visceral cinema of the first order, filmmaking that builds for more than two hours to hit with laserlike precision at just that last point. It's one of the finest pieces of filmmaking in all of '30s Hollywood, one of the vanishingly rare times that the Academy Award for Best Picture went to the actual best picture of the year, both because of its emotional power and the sublime technique that went into those emotions, and also one of the few Best Picture winners that I think would still be a classic even without that award keeping them in the public eye. For to put it as bluntly as the film's own arguments, this remains one of the only truly and completely anti-war films ever made, as angry after nine decades as the day it premiered.