Parish blues

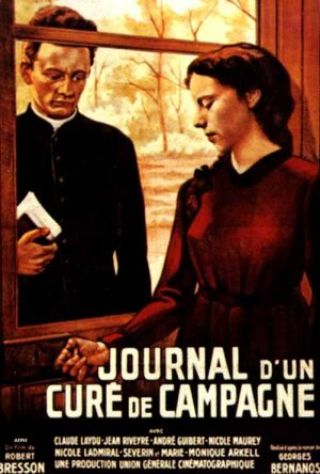

Diary of a Country Priest, from 1951, was the third feature film directed by French director Robert Bresson, and it is the hinge on which his entire career pivots. Prior to this point, he made the kind of films people were making in France in the '40s: solemn melodramas for respectable middle class audiences who preferred some level of artistry in their movies. After this point, he made a kind of movie that basically nobody else was making in France or the the rest of the world, and nobody ever has since: unrelentingly spare dramas that go beyond minimalism into such a purified register that it feels almost like watching the essence of a movie rather than the movie itself. Diary of a Country Priest (adapted from a celebrated novel by Georges Bernanos) straddles the lines between these two phases of his career: it has all the trappings of a mature Bresson film without the severity. That would come with his next film, 1956's A Man Escaped, a prison break movie made with at such a level of austerity that we never see the prison. Comparatively, this film actually resembles, like, a movie.

Still, if this feels like a tentative steps towards Bresson's final form in retrospect, let us place ourselves into the context of 1951. And in 1951, this is still plenty severe. It is the movie where Bresson first came up with the two stylistic techniques that most famously defined his style going forward: his use of what he called "models", nonprofessional actors cast for their physical appearance, and then over-rehearsed until their performances had become so flat and disaffected as to barely resemble performing at all. It's a style that has been designed to incorporate the humans in a film into the mechanical construction of the film, reducing them to the purely visual, emptying them out so they can then be refilled as a cinematic element. When done well, it's a way of creating shockingly new experiences, defamiliarising basic human behavior to refresh it and thus make it more immediate and engaging.

Even here, we find that Diary of a Country Priest is something of a transitional work. The lead actor, Claude Laydu, was a young stage actor, and hasn't gone quite a flat as Bresson's actors would later (nor, it would seem, as flat as Bresson would have preferred). There are key moments where Laydu is clearly "acting", and to be sure, doing a damn fine job of it. In the presence of so much detached "modeling", it takes very little for even the slightest deliberate, calculated shift in expression to have a great impact, and this is largely how Laydu's performance is built across the film: he stares steadily and inexpressively while most of the work of explicitly fleshing out his character is done through his voice-over. At certain key plot points, the mask that he's set his face into relaxes into a recognisable emotion - this is, indeed, one of the ways that the film cues us to notice these as key points. If the results are less astonishing in creating emotions as something external to the human than in Bresson's more adventurous later work, they are nonetheless inordinately powerful and moving; the central point that thrusts the film from its ambivalent opening hour into its purposeful, if somber closing hour is carried off on a moment of acting that's slight and sudden and feels so urgent and alive that it feels like a whole film packed into just several seconds of another one.

The curé of the title, Laydu's character, has no name that we ever learn. He's astonishingly young (Laydu was 23 when the film premiered), and newly arrived to the parish at the northern town of Ambricourt, but already overwhelmed by the concerns of a chilly world: as he writes in his diary, he is gripped by the fear that he has no means of reaching out to the people whose souls he has taken responsibility for, and it is not even clear that they want him to. Instead, he is wracked by doubt and physical weakness, able to eat nothing richer than stale bread soaked in wine for fear of upsetting his fragile stomach. His voice, detached from his body and anchored by the words he scratches out in his notebook, are our constant companion throughout the film: we watch as he interacts with the world, as the soundtrack reveals his reflections on his own failings and the world he is trying to desperately to save. This disconnect between sound and image is, by the way, the other stylistic technique that would come to define the Bresson approach: we rarely see what we hear, and we often don't hear what we see. Like his use of models, this would be refined to the point of a terrifying perfection as soon as A Man Escaped; but it's already doing plenty of work right here in Diary of a Country Priest, making it quite clear that the diary is just as crucial to the film as the priest himself. The film exists simultaneously in three time frames: the events of his day, as he struggles to do good, his later reflections on his behavior, and our still later position encountering his diary entries from some time later. The act of writing and reflecting is the main action of the movie, not his interactions with his parishioners.

This makes the film into a kind of reverse-confessional. Bresson was one of cinema's foremost Catholics, and his work is saturated with a quiet desperation at the question of how we are to keep faith in the good and holy if the world around is full of suffering. But he generally couched this in abstractions. Only three of his films are on explicitly religious themes: his first, Angels of Sin, from 1943, and Trial of Joan of Arc, from 1962, alongside this one. Of these, Diary of a Country Priest is the one that's most interested in explicitly grappling with big questions, and with the nature of religion in a world moving away from it. Compared to the two films that most directly copy its matter, Ingmar Bergman's 1963 Winter Light and Paul Schrader's 2017 First Reformed (the latter is in some ways almost a direct remake), this isn't as crushingly pessimistic, though it's certainly nobody's idea of an "up" film. But it does have that remarkable two-part structure, which shifts the priest's outlook from nihilistic despair to some hope that there is, somewhere beyond our current knowledge, meaning to all of this. It's definitely not comforting, but it allows the possibility that there is comfort to be found, somewhere in the ineffable, unknowable world beyond our perception.

It also has Laydu, who does so very much to ground this philosophical treatise in the concrete and human. His boyishness is significant to the narrative, but it also does much to drive the film's themes and feelings: the film's perspective feels much older than the priest's (Bresson was nearing 50 when the film opened), and its viewer is invited to look on him both as a complicated, conflicted thinker asking impossibly mature questions, but also as a helpless young man lost in a world that refuses to make a place for him. I'm not even sure if the actor is doing anything to boost that feeling, or if it's simply Bresson's "model" approach bearing fruit, as he cuts the film around Laydu's concerned, slack face to accentuate a sense of isolation and confusion.

Whatever the case, the film is potent stuff, managing to marry human concerns with cosmic questions without making a big deal about either, and without giving either short shrift. I confess to not finding it quite top-tier Bresson; for one thing, it suffers from a thoroughly conventional score by Jean-Jacques Grunenwald that makes some scenes needlessly sentimental, in a very annoying, pushy way. Given that Bresson's later career would be so vigorously dedicated to giving the viewer space to have their own reaction, untouched by any heavy authorial insistence, this feels like an especially irritating intrusion. And that's the thing, this isn't mature Bresson: his striking use of offscreen sound is still developing, his latter method of building stories out of slivers of information and hazy ellipses is almost there, but the film still makes sure to fill in its gaps. For any other filmmaker of the 1950s, this would be an outright masterpiece; for Bresson, it feels more like a very good step in the right direction. Still, if one can shake loose the knowledge of what was to come, there's almost nothing here that's lacking: it is a portrait of tormented, doubting faith that finds itself and meets the uncertain future with dignity and acceptance that sensationalises nothing and portrays the priest with the same simple grace that he tries to live. It is a troubled film, but not a hopeless one, and this does set it aside, to its benefit, from the great bulk of '50s and '60s "God is silent" movies, including some of Bresson's own (compare the calm absolution that ends this film to the Christ-donkey dying alone and ignored at the end of 1966's Au hasard Balthazar). It is a film suggesting that, when all we have is faith, that faith must be nurtured and developed to remain strong against the suffering that will test it, and in those handful of moments when the priest's faith is rewarded - faith in himself and other humans, more than in the divine, I must add - Diary of a Country Priest becomes so quietly beautiful as to be overwhelming.

Still, if this feels like a tentative steps towards Bresson's final form in retrospect, let us place ourselves into the context of 1951. And in 1951, this is still plenty severe. It is the movie where Bresson first came up with the two stylistic techniques that most famously defined his style going forward: his use of what he called "models", nonprofessional actors cast for their physical appearance, and then over-rehearsed until their performances had become so flat and disaffected as to barely resemble performing at all. It's a style that has been designed to incorporate the humans in a film into the mechanical construction of the film, reducing them to the purely visual, emptying them out so they can then be refilled as a cinematic element. When done well, it's a way of creating shockingly new experiences, defamiliarising basic human behavior to refresh it and thus make it more immediate and engaging.

Even here, we find that Diary of a Country Priest is something of a transitional work. The lead actor, Claude Laydu, was a young stage actor, and hasn't gone quite a flat as Bresson's actors would later (nor, it would seem, as flat as Bresson would have preferred). There are key moments where Laydu is clearly "acting", and to be sure, doing a damn fine job of it. In the presence of so much detached "modeling", it takes very little for even the slightest deliberate, calculated shift in expression to have a great impact, and this is largely how Laydu's performance is built across the film: he stares steadily and inexpressively while most of the work of explicitly fleshing out his character is done through his voice-over. At certain key plot points, the mask that he's set his face into relaxes into a recognisable emotion - this is, indeed, one of the ways that the film cues us to notice these as key points. If the results are less astonishing in creating emotions as something external to the human than in Bresson's more adventurous later work, they are nonetheless inordinately powerful and moving; the central point that thrusts the film from its ambivalent opening hour into its purposeful, if somber closing hour is carried off on a moment of acting that's slight and sudden and feels so urgent and alive that it feels like a whole film packed into just several seconds of another one.

The curé of the title, Laydu's character, has no name that we ever learn. He's astonishingly young (Laydu was 23 when the film premiered), and newly arrived to the parish at the northern town of Ambricourt, but already overwhelmed by the concerns of a chilly world: as he writes in his diary, he is gripped by the fear that he has no means of reaching out to the people whose souls he has taken responsibility for, and it is not even clear that they want him to. Instead, he is wracked by doubt and physical weakness, able to eat nothing richer than stale bread soaked in wine for fear of upsetting his fragile stomach. His voice, detached from his body and anchored by the words he scratches out in his notebook, are our constant companion throughout the film: we watch as he interacts with the world, as the soundtrack reveals his reflections on his own failings and the world he is trying to desperately to save. This disconnect between sound and image is, by the way, the other stylistic technique that would come to define the Bresson approach: we rarely see what we hear, and we often don't hear what we see. Like his use of models, this would be refined to the point of a terrifying perfection as soon as A Man Escaped; but it's already doing plenty of work right here in Diary of a Country Priest, making it quite clear that the diary is just as crucial to the film as the priest himself. The film exists simultaneously in three time frames: the events of his day, as he struggles to do good, his later reflections on his behavior, and our still later position encountering his diary entries from some time later. The act of writing and reflecting is the main action of the movie, not his interactions with his parishioners.

This makes the film into a kind of reverse-confessional. Bresson was one of cinema's foremost Catholics, and his work is saturated with a quiet desperation at the question of how we are to keep faith in the good and holy if the world around is full of suffering. But he generally couched this in abstractions. Only three of his films are on explicitly religious themes: his first, Angels of Sin, from 1943, and Trial of Joan of Arc, from 1962, alongside this one. Of these, Diary of a Country Priest is the one that's most interested in explicitly grappling with big questions, and with the nature of religion in a world moving away from it. Compared to the two films that most directly copy its matter, Ingmar Bergman's 1963 Winter Light and Paul Schrader's 2017 First Reformed (the latter is in some ways almost a direct remake), this isn't as crushingly pessimistic, though it's certainly nobody's idea of an "up" film. But it does have that remarkable two-part structure, which shifts the priest's outlook from nihilistic despair to some hope that there is, somewhere beyond our current knowledge, meaning to all of this. It's definitely not comforting, but it allows the possibility that there is comfort to be found, somewhere in the ineffable, unknowable world beyond our perception.

It also has Laydu, who does so very much to ground this philosophical treatise in the concrete and human. His boyishness is significant to the narrative, but it also does much to drive the film's themes and feelings: the film's perspective feels much older than the priest's (Bresson was nearing 50 when the film opened), and its viewer is invited to look on him both as a complicated, conflicted thinker asking impossibly mature questions, but also as a helpless young man lost in a world that refuses to make a place for him. I'm not even sure if the actor is doing anything to boost that feeling, or if it's simply Bresson's "model" approach bearing fruit, as he cuts the film around Laydu's concerned, slack face to accentuate a sense of isolation and confusion.

Whatever the case, the film is potent stuff, managing to marry human concerns with cosmic questions without making a big deal about either, and without giving either short shrift. I confess to not finding it quite top-tier Bresson; for one thing, it suffers from a thoroughly conventional score by Jean-Jacques Grunenwald that makes some scenes needlessly sentimental, in a very annoying, pushy way. Given that Bresson's later career would be so vigorously dedicated to giving the viewer space to have their own reaction, untouched by any heavy authorial insistence, this feels like an especially irritating intrusion. And that's the thing, this isn't mature Bresson: his striking use of offscreen sound is still developing, his latter method of building stories out of slivers of information and hazy ellipses is almost there, but the film still makes sure to fill in its gaps. For any other filmmaker of the 1950s, this would be an outright masterpiece; for Bresson, it feels more like a very good step in the right direction. Still, if one can shake loose the knowledge of what was to come, there's almost nothing here that's lacking: it is a portrait of tormented, doubting faith that finds itself and meets the uncertain future with dignity and acceptance that sensationalises nothing and portrays the priest with the same simple grace that he tries to live. It is a troubled film, but not a hopeless one, and this does set it aside, to its benefit, from the great bulk of '50s and '60s "God is silent" movies, including some of Bresson's own (compare the calm absolution that ends this film to the Christ-donkey dying alone and ignored at the end of 1966's Au hasard Balthazar). It is a film suggesting that, when all we have is faith, that faith must be nurtured and developed to remain strong against the suffering that will test it, and in those handful of moments when the priest's faith is rewarded - faith in himself and other humans, more than in the divine, I must add - Diary of a Country Priest becomes so quietly beautiful as to be overwhelming.